In the first decade of the 20th century, only a few regions on the African continent were still controlled by sovereign kingdoms. One of these was the Lozi kingdom, a vast state in south-central Africa covering nearly 250,000 sqkm that was led by a shrewd king who had until then, managed to retain his autonomy.

The Lozi kingdom was a powerful centralized state whose history traverses many key events in the region, including; the break up of the Lunda empire, the Mfecane migrations, and the colonial scramble. In 1902, the Lozi King Lewanika Lubosi traveled to London to meet the newly-crowned King Edward VII in order to negotiate a favorable protectorate status. He was met by another African delegate from the kingdom of Buganda who described him as "a King, black like we are, he was not Christian and he did what he liked"1

This article explores the history of the Lozi kingdom from the 18th century to 1916, and the evolution of the Lozi state and society throughout this period.

Map of Africa in 1880 highlighting the location of the Lozi kingdom (Barosteland)2

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early history of the Lozi kingdom

The landscape of the Lozi heartland is dominated by the Zambezi River which cuts a bed of the rich alluvial Flood Plain between the Kalahari sands and the miombo woodlands in modern Zambia.

The region is dotted with several ancient Iron Age sites of agro-pastoralist communities dating from the 1st/5th century AD to the 12th/16th century, in which populations were segmented into several settlement sites organized within lineage groups.3 It was these segmented communities that were joined by other lineage groups arriving in the upper Zambezi valley from the northern regions under the Lunda empire, and gradually initiated the process of state formation which preceded the establishment of the Lozi kingdom.4

The earliest records and traditions about the kingdom's founding are indirectly associated with the expansion and later break-up of the Lunda empire, in which the first Lozi king named Rilundo married a Lunda woman named Chaboji. Rulindo was succeeded by Sanduro and Hipopo, who in turn were followed by King Cacoma Milonga, with each king having lived long enough for their former capitals to become important religious sites.5

The above tradition about the earliest kings, which was recorded by a visitor between 1845-1853, refers to a period when the ruling dynasty and its subjects were known as the Aluyana and spoke a language known as siluyana. In the later half of the 19th century, the collective ethnonym for the kingdom's subjects came to be known as the lozi (rotse), an exonym that emerged when the ruling dynasty had been overthrown by the Makololo, a Sotho-speaking group from southern Africa. 6

King Cacoma Milonga also appears in a different account from 1797, which describes him as “a great souva called Cacoma Milonga situated on a great island and the people in another.” He is said to have briefly extended his authority northwards into Lunda’s vassals before he was forced to withdraw.7 He was later succeeded by King Mulambwa (d. 1830) who consolidated most of his predecessors' territorial gains and reformed the kingdom's institutions inorder to centralize power under the kingship at the expense of the bureaucracy.8

Mulambwa is considered by Lozi to have been their greatest king, and it was during his very long reign that the kingdom’s political, economic, and judicial systems reached that degree of sophistication noted by later visitors.9

the core territories of the Lozi kingdom10

The Government in 19th century buLozi

At the heart of the Lozi State is the institution of kingship, with the Lozi king as the head of the social, economic and administrative structures of the whole State. After the king's death, they're interred in a site of their choosing that is guarded by an official known as Nomboti who serves as an intermediary between the deceased king and his successors and is thus the head of the king's ancestral cult.11

The Lozi bureaucracy at the capital, which comprised the most senior councilors (Indunas) formed the principal consultative, administrative, legislative, and judicial bodies of the nation. A single central body the councilors formed the National Council (Mulongwanji) which was headed by a senior councilor (Ngambela) as well as a principal judge (Natamoyo) . A later visitor in 1875 describes the Lozi administration as a hierarchy of “officers of state” and “a general Council” comprising “state officials, chiefs, and subordinate governors,” whose foundation he attributed to “a constitutional ruler now long deceased”.12

The councilors were heads of units of kinship known as the Makolo, and headed a provincial council (kuta) which had authority over individual groups of village units (silalo) that were tied to specific tracts of territories/land. These communities also provided the bulk of the labour and army of the kingdom, and in the later years, the Makolo were gradually centralized under the king who appointed non-hereditary Makolo heads. This system of administration was extended to newly conquered regions, with the southern capital at Nalolo (often occupied by the King’s sister Mulena Mukwai), while the center of power remained in the north with the roving capital at Lealui.13

The valley's inhabitants established their settlements on artificially built mounds (liuba) tending farms irrigated by canals, activities that required large-scale organized labor. Some of the surplus produced was sent to the capital as tribute, but most of the agro-pastoral and fishing products were exchanged internally and regionally as part of the trade that included craft manufactures and exports like ivory, copper, cloth, and iron. Long-distance traders from the east African coast (Swahili and Arab), as well as the west-central African coast (Africans and Portuguese), regularly converged in Lozi’s towns.14

Palace of the King (at Lealui) ca. 1916, Zambia. USC Libraries.

Palace of the Mulena Mukwai/Mokwae (at Nalolo), 1914, Zambia. USC Libraries.

The Lozi kingdom under the Kololo dynasty.

After the death of Mulambwa, a succession dispute broke out between his sons; Silumelume in the main capital of Lealui and Mubukwanu at the southern capital of Nalolo, with the latter emerging as the victor. But by 1845, Mubukwanu's forces were defeated in two engagements by a Sotho-speaking force led by Sebetwane whose followers (baKololo) had migrated from southern Africa in the 1820s as part of the so-called mfecane. Mubukwanu's allies fled to exile and control of the kingdom would remain in the hands of the baKololo until 1864.15

Sebetwane (r. 1845-1851) retained most of the pre-existing institutions and complacent royals like Mubukwanu's son Sipopa, but gave the most important offices to his kinsmen. The king resided in the Caprivi Strip (in modern Namibia) while the kingdom was ruled by his brother Mpololo in the north, and daughter Mamochisane at Nololo, along with other kinsmen who became important councilors. The internal agro-pastoral economy continued to flourish and Lozi’s external trade was expanded especially in Ivory around the time the kingdom was visited by David Livingstone in 1851-1855, during the reign of Sebetwane's successor, King Sekeletu (r. 1851-1864).16

The youthful king Sekeletu was met with strong opposition from all sections of the kingdom, spending the greater part of his reign fighting a rival candidate named Mpembe who controlled most of the Lozi heartland. After Sekeletu's death in 1864, further succession crisis pitted various royals against each other, weakening the control of the throne by the baKololo. The latter were then defeated by their Luyana subjects who (re)installed Sipopa as the Lozi king. While the society was partially altered under baKololo rule, with the Luyana-speaking subjects adopting the Kololo language to create the modern Lozi language, most of the kingdom’s social institutions remained unchanged.17

The (re) installation of King Sipopa (r. 1864-1876) involved many Lozi factions, the most powerful of which was led by a nobleman named Njekwa who became his senior councilor and was married to Sipopa's daughter and co-ruler Kaiko at Nalolo. But the two allies eventually fell out and shortly after the time of Njekwa's death in 1874, the new senior councilor Mamili led a rebellion against the king in 1876, replacing him with his son Mwanawina. The latter ruled briefly until 1878 when factional struggles with his councilors drove him off the throne and installed another royal named Lubosi Lewanika (r.1878-84, 1885-1916) while his sister and co-ruler Mukwae Matauka was set up at Nalolo.18

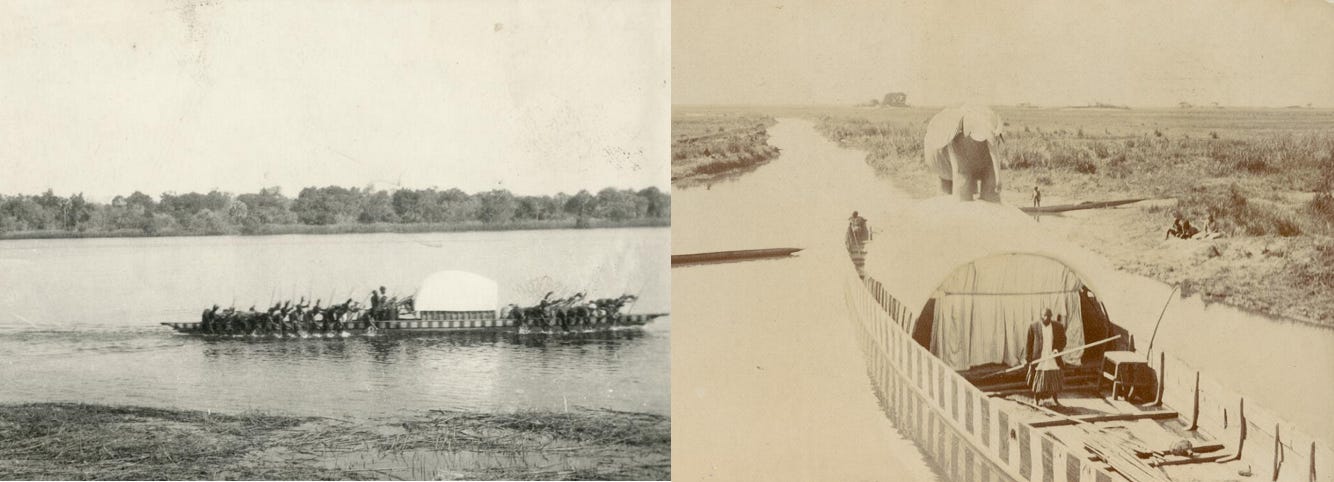

The Royal Barge on the Zambezi river, ca. 1910, USC Library

King Lewanika’s Lozi state

During King Lubosi Lewanika's long reign, the Lozi state underwent significant changes both internally as the King's power became more centralized, and externally, with the appearance of missionaries, and later colonialists.

After King Lubosi was briefly deposed by his powerful councilor named Mataa in favor of King Tatila Akufuna (r. 1884-1885), the deposed king returned and defeated Mataa's forces, retook the throne with the name Lewanika, and appointed loyalists. To forestall external rebellions, he established regional alliances with King Khama of Ngwato (in modern Botswana), regularly sending and receiving embassies for a possible alliance against the Ndebele king Lobengula. He instituted several reforms in land tenure, created a police force, revived the ancestral royal religion, and created new offices in the national council and military.19

King Lewanika expanded the Lozi kingdom to its greatest extent by 1890, exercising varying degrees of authority over a region covering over 250,000 sqkm20. This period of Lozi expansion coincided with the advance of the European missionary groups into the region, followed by concessioners (looking for minerals), and the colonialists. Of these groups, Lewanika chose the missionaries for economic and diplomatic benefits, to delay formal colonization of the kingdom, and to counterbalance the concessionaries, the latter of whom he granted limited rights in 1890 to prospect for minerals (mostly gold) in exchange for protection against foreign threats (notably the powerful Ndebele kingdom in the south and the Portuguese of Angola in the west).21

The Lozi kingdom at its greatest extent in the late 19th century

Lewanika oversaw a gradual and controlled adoption of Christianity (and literacy) confined to loyal councilors and princes, whom he later used to replace rebellious elites. He utilized written correspondence extensively with the various missionary groups and neighboring colonial authorities, and the Queen in London, inorder to curb the power of the concessionaires (led by Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa company which had taken over the 1890 concession but only on paper), and retain control of the kingdom. He also kept updated on concessionary activities in southern Africa through diplomatic correspondence with King Khama.22

The king’s Christian pretensions were enabled by internal factionalism that provided an opportunity to strengthen his authority. Besides the royal ancestral religion, lozi's political-religious sphere had been dominated by a system of divination brought by the aMbundu (from modern Angola) whose practitioners became important players in state politics in the 19th century, but after reducing the power of Lewanika's loyalists and the king himself, the later purged the diviners and curbed their authority.23

This purge of the Mbundu diviners was in truth a largely political affair but the missionaries misread it as a sign that the King was becoming Christian and banning “witchcraft”, even though they were admittedly confused as to why the King did not convert to Christianity. Lewanika had other objectives and often chided the missionaries saying; "What are you good for then? What benefits do you bring us? What have I to do with a bible which gives me neither rifles nor powder, sugar, tea nor coffee, nor artisans to work for me."24

The newly educated Lozi Christian elite was also used to replace the missionaries, and while this was a shrewd policy internally as they built African-run schools and trained Lozi artisans in various skills, it removed the Lozi’s only leverage against the concessionaires-turned-colonists.25

The Lozi kingdom in the early 20th century: From autonomy to colonialism.

The King tried to maintain a delicate balance between his autonomy and the concessionaries’ interests, the latter of whom had no formal presence in the kingdom until a resident arrived in 1897, ostensibly to prevent the western parts of the kingdom (west of the Zambezi) from falling under Portuguese Angola. While the Kingdom was momentarily at its most powerful and in its most secure position, further revisions to the 1890 concessionary agreement between 1898 and 1911 steadily eroded Lewanika's internal authority. 26

Internal opposition by Lozi elites was quelled by knowledge of both the Anglo-Ndebele war of 1893 and the Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902. But it was the Anglo-Boer war that influenced the Lozi’s policies of accommodation in relation to the British, with Lozi councilors expressing “shock at the thought of two groups of white Christians slaughtering each other”.27 The war illustrated that the Colonialists were committed to destroying anyone that stood in their way, whether they were African or European, and a planned expulsion of the few European settlers in Lozi was put on hold.

Always hoping to undermine the local colonial governors by appealing directly to the Queen in London, King Lewanika prepared to travel directly to London at the event of King Edward’s coronation in 1902, hoping to obtain a favorable agreement like his ally, King Khama had obtained on his own London visit in 1895. When asked what he would discuss when he met King Edward in London, the Lozi king replied: “When kings are seated together, there is never a lack of things to discuss.”28

King Lewanika (front seat on the left) and his entourage visiting Deeside, Wales, ca. 1901, Aberdeen archives

It is likely that the protection of western Lozi territory from the Portuguese was also on the agenda, but the latter matter was considered so important that it was submitted by the Portuguese and British to the Italian king in 1905, who decided on a compromise of dividing the western region equally between Portuguese-Angola and the Lozi. While Lewanika had made more grandiose claims to territory in the east and north that had been accepted, this one wasn’t, and he protested against it to no avail29

After growing internal opposition to the colonial hut tax and the King’s ineffectiveness had sparked a rebellion among the councilors in 1905, the colonial governor sent an armed patrol to crush the rebellion, This effectively meant that Lewanika remained the king only nominally, and was forced to surrender the traditional authority of Kingship for the remainder of his reign. By 1911, the kingdom was incorporated into the colony of northern Rhodesia, formally marking the end of the kingdom as a sovereign state.30

the Lozi king lewanika ca. 1901. Aberdeen archives

A few hundred miles west of the Lozi territory was the old kingdom of Kongo, which created an extensive international network sending its envoys across much of southern Europe and developed a local intellectual tradition that includes some of central Africa’s oldest manuscripts.

Read more about it here:

Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain 1901-1914 By Jeffrey Green pg 22

Map by Sam Bishop at ‘theafricanroyalfamilies’

Iron Age Farmers in Southwestern Zambia: Some Aspects of Spatial Organization by Joseph O. Vogel

Iron Age History and Archaeology in Zambia by D. W. Phillipson

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton pg 310, Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 18-20)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 5, 10-15)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By John K. Thornton pg 310)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 57-59)

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 2

Map by Mutumba Mainga

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 30)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 38-41, The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 3-5

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 33-36, 44-47, 50-54)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 32, 130-131)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 61-71)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 74-82, The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 9-11

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 87-92, The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 11-12

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 103-113, The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 13-15

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 19- 34 Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 115- 136)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia pg 150-161)

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 38-56, Barotseland's Scramble for Protection by Gerald L. Caplan pg 280-285

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 174-175)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 137-138)

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 179-182)

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 76-81

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 63-68, 74-75

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 76

Bulozi under the Luyana Kings: Political Evolution and State Formation in Pre-colonial Zambia by Mutumba Mainga pg 192)

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 88-89.

The Elites of Barotseland 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia's Western Province by Gerald L. Caplan pg 90-103