Africa's 100 years' war at the dawn of colonialism: The Anglo-Asante wars (1807-1900)

On the misconceptions about Africa's "rapid" conquest.

The colonial invasion of Africa in the late 19th century is often portrayed in popular literature as a period when the technologically advanced armies of western Europe rapidly advanced into the African interior meeting little resistance from Africans armed with rudimentary weapons. Its often assumed that African states and their armies were unaware of the threat posed by European military advances and unreceptive to military technologies that would have greatly improved their ability to retain political autonomy.

All accounts of African military history however, dispel these rather popular misconceptions. From 1807 to 1900, the army of the Asante kingdom fought five major battles and dozens of skirmishes with the British to maintain its independence, this west-African kingdom had over the 17th and 18th century expanded to cover much of what is now the modern country of Ghana, ruling a population of just under a million people in a region roughly the size of the United Kingdom. By the 19th century, Asante had a massive army with relatively modern weapons that managed to defeat and hold off several British attacks for nearly a century. It wasn’t until the combined effects of the British arms blockade, the late-19th century invention of quick-firing guns and the Asante’s internal political crisis, that the Asante lost their independence to the British.

The evolution of the Anglo-Asante wars is instructive in understanding why, after nearly 500 years of failed attempts at colonizing the Africa interior, the European armies eventually managed to tip the balance of power against African armies. This article explores the history of the Asante with a brief account on the political and economic context of the Anglo-Asante conflict and an overview of the each of the major wars between the Asante armies and the British.

Map of the Asante kingdom at its greatest extent in 1807.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Asante origins, political institutions and trade.

The Asante was the last of the major Akan kingdoms founded by Twi-speakers that arose in the early 2nd millennium in the "forest region" of what is now modern Ghana. Akan society came into existence as a result of a change in the foraging mode of production to an agricultural one, this agrarian system was supported by the production and sale of gold, both of which necessitated the procurement, organization and supply of labor which led to the emergence of political structures that coalesced into the earliest Akan polities.1 By the 17th century, the largest of these Akan polities was Denkyira in the interior and Akwamu near the coast; the former controlled some of the largest gold deposits in the region (the entire region funneled approximately 56 tonnes of gold between 1650-1700 to the trans-saharan and European markets but these revenues were shared among many states), and it also possessed the largest army among the Akan states which enabled it to dominate its smaller peers as their suzerain. One of these states was the incipient Asante polity in the “Kwaman region” centered at the gold-trading town of Tafo that was contested between several small Akan polities, it was here that the powerful lineage groups elected Osei Tutu to consolidate the conquests of his predecessors using the knowledge of statecraft and warfare that he had acquired from his stay at the courts of Denkyira and Akwamu (who supported his conquests in exchange for tribute). He defeated several of the smaller Kwaman polities in the 1680s and founded the Asante state at his capital Kumasi as the first Asantehene (king). It was then that Asante first appears in external sources in 1698.2

The early eighteenth century was a period that was characterized by expansionist wars of conquest, the first was the defeat of Denkyira in 1701, which occurred after Asante's gradual assimilation of immigrant lineage groups from Denkyira3 ,after this were dozens of wars that removed the power of Asante's competitors to its north, south, east and west especially during the reign of Asantehene Opuku Ware (1720–1750) who is credited with the creation of imperial Asante (see map below), these conquered territories were then gradually incorporated into the Asante administration as tributary states.4

Asante campaigns in the 18th century.

Throughout the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, the Asante state became increasingly complex, enlarging the number of its personnel, developing and embedding novel specializations of function, and greatly extending its affective competence and range. In its process of bureaucratization, the executive and legislative functions of governing imperial Asante became more centralized and concentrated at Kumase by the mid 18th century, with the formation of a council of Kumase office holders presided over by the Asantehene5. This powerful council which met regularly, was in charge of the day-to-day operations of the state as well as the election of the King, and it increasingly came to supplant the roles of the older and larger national council/assembly (Asantemanhyiamu) which met annually, as a result of the expansive conquests that rendered the latter's decision making processes inefficient. The Asantemanhyiamu was was thus relegated to the more fundamental constitutional and juridical issues as well as actions taken by the Kumasi council.6

Illustrations of; the palace of King Kofi after it was looted in the 1874 invasion, a street scene in Kumasi.

Asante expansionism was enabled by its large military. The standing army at Kumase was headed by a commander in chief who was subordinated by generals and captains, this central unit was supported by several forces from the provinces which were provided by vassal provinces, and often came to number upto 80,000 men at its largest. This relatively high number of soldiers was enabled by Asante's fairly high population and urbanization with an estimated state population of 750,000 in the 1820s; and with cities and towns such as Kumase, Dwaben, Salaga and Bondouku having an estimated population of 35-15,000 people.7 Asante’s weapons and ammunition were provided by the the state in the case of national war8, by the time of Asante’s ascendance in the 18th century, all wars in the “gold coast” region were fought with fire-arms, primarily the flintlock rifles called “dane guns”, but swords were also carried ceremonially and attimes used in hand-hand combat.9 The Asante purchased these guns in large quantities and in the early 19th century with more than ten thousand purchased annually in the 1830s, they had gun repair shops, and could make blunderbusses that could fire led-slugs which were their most common type of ammunition. This level of military technology was sufficient in the early 19th century whether against African or European foes, but in the later half of the century increasingly proved relatively inefficient. 10(as i will cover, this was because the Asante refused to purchase better guns or ammunition but an effective blockade against supplying the Asante combined with the inability to manufacture modern rifles locally). The Asante army structure also wasn't static but evolved with time depending on the internal political currents and military threats. In the mid 19th century, a system of platoons of twenty men was introduced, their techniques of loading and reloading were able to sustain a fairly stable fusillade of fire, and in the early 1880s, the system of military conscription was largely replaced by a force of paid soldiers.11

modified flintlock pistol with brass tucks from Asante dated to 1870 ( 97.1308 boston museum of fine arts)

Asante soldier holding a rifle (photo from the international mission photography Archive, c. 1885-1895)12

From the late 17th to early 18th century gold comprised nearly 2/3rds of the Asante exports to the European traders in the south, and the vast majority of Asante exports to the northern and trans-Saharan routes. As the result of the conquests and increased tribute from its northern territories, Asante southern exports in 1730s-1780s were slaves, by the late 18th century however, Kola supplanted slaves as the Asante's main export. Asante’s commodities trade further grew after the fall in slave trade in the 1810s, and the kingdom’s exports of Kola rose to a tune of 270 tonnes a year in 1850s while Gold rose to a tune of around 45 tonnes over 50 years between 1800-1850, both of these commodities outstripped the value of the mid 18th century export of slaves and enabled Asante to fully withdraw from the Atlantic commerce and focus more on the northern export markets to the savannah region of west-Africa, especially in the newly established west African empires of Segu, Hamdallaye and Sokoto in the 18th and 19th century that were located in Mali and northern Nigeria13. The surplus wealth generated by state officials and private merchants from the northern Kola trade was often converted into gold dust. The centrality of gold in the economy and culture of Asante can't be understated, it was the command of gold as a disposable resource that permitted the accumulation of convertible surpluses in labor and produce, and it was the entrepreneurial deployment of gold that initiated, and then embedded and accelerated the crucial processes of differentiation in Asante society.14

Gold ornaments of the Asante including gold discs, rings and headcaps (photos from the british museum and houston museum of fine arts)

Throughout the 19th century, the Asante state sedulously encouraged, structured and rewarded the pursuit of the fundamentally ingrained social ethic of achievement through accumulation, and it also commanded and mediated access to wealth stored in gold dust. As a consequence, it was the state's servants such as office holders, titled functionaries, state traders as well as private entrepreneurs (men of wealth) who accumulated vast amounts of wealth, whose value constituted "fairly substantial sums of money even by the standards of contemporary early nineteenth-century Europeans". The state treasury in the 1860s (the "great chest) held about 400,000 ounces of gold, valued then at £ 1.4m (just under £200m today) while titled figures such as Boakye Yam and Apea Nyanyo who were active in the early 19th century, owned as much as £176,000, £96,000 of gold dust (about £16m, £8.6m today). The wealth and security enjoyed by Asante elites encouraged the development of alternative policy options to warfare, and with time came to dominate Asante's foreign policy at Kumase in the 19th century.15

19th century Asante treasure box made of brass mounted on a 4-wheeled stand, likely a replica of the great chest (pitt rivers museum)16

The road network of the Asante : (read more about it on my patreon)

Northern commerce, northern conquests and the origins of Asante’s southern conflict with the British.

Despite the growing influence of the mercantile class in the decision making process at Kumase which favored the consolidation of conquests rather than renewed expansion, the strength of the Asante economy was largely underpinned by its military power, the campaigns of the Asante army in the late 18th century for example reveal the primarily economic rationale for its conquests, especially in its northern overtures, that were intended to protect the lucrative trade routes to the north17. One of these routes passed through the town of Salaga, that had become the principal northern emporium of Asante as a result of its centrality in the kola and gold export route that extended to Sokoto. The market of Salaga had grown at the expense of the other cities such as Bondouku, located in the vassal state of Gyaman, and had in the 18th century been the main northern town with a substantial trading diaspora of Wangara and Hausa merchants who were active in the west african empires of the savannah. Gyaman had been a hotbed of rebellions in the late 18th century but had been brought under Asante administration, although with the expansion of the Kong-Wattara kingdom from Asante’s north-east, the threat of a Gyaman break-away was more potent than ever. Wattara took advantage of the Gyaman’s disgruntlement over the shifting of trade to Salaga to instigate a rebellion in 1818 that was subsequently crushed by the Asante who were however forced to occupy the region as the continued threat of rebellion as well as the Segu empire in Mali, which had led an incursion near Gyaman during the ensuing conflict.18

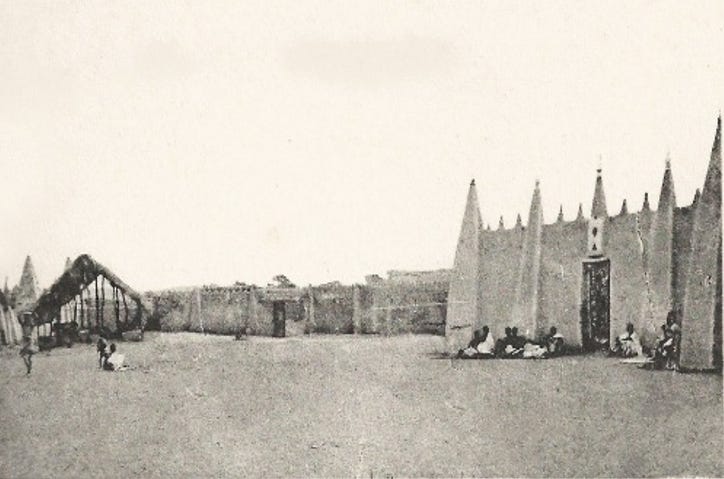

section of Bondouku in (Ivory coast) near one of samory’s residences, photo from the early 1900s

The Gyaman campaign was expensive and protracted, with hostilities extending well into the 1830s, the Asante therefore sought to cover this cost by raising taxes on its southern-western coastal provinces of the Fante, Denkyera and Assim located near the cape-coast castle. These provinces had only been pacified fairly recently in the 1807 over their non-payment of tribute and they often took advantage of the northern campaigns to wean themselves of Kumase's authority, but by 1816 , most had submitted to Asante authority, and this submission extended to the european forts within them such as the British-owned Cape coast castle, and the Dutch-owned Elmina castle, both of which recognized the authority of the Asantehene with Elmina coming under the direct control of Asante in 1816,19 and the cape-coast castle signing a treaty in February 1817 that recognized Asante’s sovereignty over the surrounding south-western provinces20. In 1818 and 1819, however, officials from Kumase arrived at cape coast to demand the usual tribute (and rent from the forts) plus the newly imposed taxes of the Gyaman war, which the southern vassals promptly refused to pay, largely due to the backing of the cape-coast's British governor John Hope Smith. Negotiations between the British and their coastal allies versus the Asante stalled for several years despite the dispatching of Thomas Bowditch in 1817 and Joseph Dupuis in 1820 by the metropolitan government in London; both of whom were well received in Kumase to affirm the 1817 treaty, but their intentions of peace were strongly opposed by the cape-coast governor21. Despite Bowditch’s good reception at Kumase, the Asante government wasn't unaware of the cape-coast governor’s hostility, knowing that the treaty he signed in 1817 wasn’t in good faith. The Asantehene Osei Bonsu (r. 1804-1824) is said to have asked Bowditch, after the latter's monologue about the glories of England and London’s intention to promote “civilization and trade” with Asante; that “how do you wish to persuade me that it is only for so flimsy a motive that you have left this fine and happy England" and the next day, a prince asked Bowditch to explain "why, if Britain were so selfless, had it behaved so differently in India"22. Four years later however, the Dupuis embassy was much better received especially after he had compelled the cape-coast governor to send a large tribute to the Asantehene, and while in Kumasi, Dupuis managed to negotiate a new treaty that affirmed that all south-western provinces were firmly under the Asante, as well as formally seeking to establish ties between London and Kumase. Dupuis was escorted from Kumase by Asante envoys with whom he intended to travel to London as the appointee of the British crown, but his efforts were thwarted by Hope smith who refused to ratify the new treaty and also refused to aid the travel of the combined Anglo-Asante embassy to London. Coincidentally, the authorities in London dissolved the African Company of Merchants which owned the gold coast forts including cape-coast castle (thus deposing Hope smith) and transferred ownership directly to them British crown, appointing Charles MacCarthy as the first governor of the cape coast.

Recalling the events that preceded the Anglo-Asante wars in the context of the disputed treaties, A British resident of cape coast would in the 1850s write that "the king of Ashantee had greater regard for his written engagements than an English governor".23 While its difficult to pin-point exactly what sparked the hostility between the cape-coast governors and the Asante, the historian Gareth Austin proposed it had to do with the ending of the Atlantic slave exports, while these had been vital to the cape-coast’s economy, they were rather marginal to the Asante economy which had resumed exporting gold and Kola in the early 19th century, and had largely orienting its export trade north to the savannah, while restricting trade between the savanna and the coast. For the cape-coast, this new commodities trade was much less lucrative than the slave trade it replaced and it prompted the British to seek more direct control over the processes of trade and production initially around the fort but later over the provinces controlled by the Asante.24

Cape coast castle as it was rebuilt in the 18th century and rcently

The first series of Anglo-Asante wars from 1824-1873: Asante’s fight from the position of strength.

The new cape-coast governor Charles MacCarthy’s attitude towards Asante turned out much worse than his predecessor's, he immediately prepared for war with Asante on his arrival at cape coast in 1823 by; fortifying the fort, forcing the south-western vassals into an alliance against Asante, and defaming Osei Bonsu in his newspapers25. When Osei Bonsu passed away in November 1823, MacCarthy made the decision to strike Asante in January 1824 when he thought the government in Kumase was at its weakest. MacCarthy's forces, which numbered about 3,000 (although divided in two columns with the one headed by him numbering about 500), faced off with a small Asante force of about 2,000 that had been sent to pacify the southern provinces in 1823, this latter force was led by Kwame Butuakwa and Owusu Akara. Maccarthy's army surprised the Asante army but his forces were nevertheless crushed by the Asante, with several hundred slain including MacCarthy who was beheaded along with 9 British officers, and many were captured and taken to Kumasi in chains, with only 70 survivors scrambling back to cape coast.26 The larger British force of 2,500 later engaged this same Asante force a few weeks after this incident, but it too was defeated with nearly 900 causalities and was forced to retreat.27 This wasn’t the first time the Asante had faced off with a army of British soldiers and their allied troops from the coast, a similar battle in 1807 had ended in an Asante victory with the British suing for peace after a lengthy siege of the cape-coast castle by the Asante armies following the escape of a rebel into the British fort.28

Osei Yaw was elected Asentehene in 1824, and his first action was to strengthen the positions in the south-west and south-central regions despite the greater security demands in the rebellious northern provinces, the forces at Elmina was reinforced , and Osei Yaw himself led an attack against the British in the town of Efutu, just 8 miles from Cape-coast, where he fought them to a standstill, forcing them to fall back, and threatened to storm cape-coast, but was later forced to withdraw due to the rains and a smallpox outbreak.29 Throughout 1825, Osei Yaw sought the approval of the council at Kumase for more reinforcements to engage to British in the south, and by December 1825, he was back in the south, this time in the far south-east, near Accra where he established a camp at Katamanso with an army of about 40,000 in an open plain, while the new British governor had been busy rallying allied forces of several Fante states to grow his own force to over 50,000. After a bitter war that involved volleys of musket fire from both sides and brutal hand-to-hand combat, the Asante lost the battle in part due to the congreve rocket fire launched by the British in the heat of the battle, forcing Osei Yaw’s forces to withdrawl.30

The Asante and the British entered into a period of negotiations over a period of 5 years that were formalized in a treaty of 1831 where the Asante relinquished their right to receive tribute from a few of its south-western provinces closest to the cape-coast in exchange for a nominal recognition by the same provinces of the Asantehene's authority, although the Asante continued to recognize these southern provinces as under the Asante political orbit by right of conquest, a right which the katamanso war hadn't overturned despite challenging it31. This new treaty relieved the Asante from its southern engagements and enabled it to pacify its northern provinces, as well as increase trade in both directions that had been disrupted by the southern conflicts, the extensive Asante road system now included branches to the cape coast.32 But by the mid 19th century, most of the Asante’s export trade was oriented northwards as the kola trade through Salaga had exploded. The ensuring peace between the Asante and the British went on relatively unbroken for over 30 years, and on one occasion in 1853, some of the southern provinces sought to return to a tributary status under Asante which nearly led to a war with the British, that was only resolved with a prisoner exchange.33

In 1862, renewed conflicts over the extradition of escaped criminals set the Asante and the British on a warpath, when a wealthy Asante citizen hoarded a large gold nugget (which by Asante’s laws belonged to the royal treasure), and fled to British protected territory near the cape coast. This provided the newly appointed governor Richard pine the pretext for conquest of Asante and after rebuffing the Asantehene Kwaku Dua's request for extradition, Pine declared that he would fight “until the Kingdom of Ashantee should be prostrated before the English Government.” The Asante army rapidly advanced south into the then British “protected territories" by May 1862, pacifying the small kingdoms with little resistance from the British allies, overrunning and sacking several towns to discourage the southern statelets from joining the British, and to demonstrate the strength of the Asante forces34. After the Asante had returned to Kumase, the cape coast governor sent an expedition of about 600 well-armed British officers and thousands of their coastal allies north to attack Kumase, but this force was ill prepared for the forested region and was forced to retreat, leaving many of the heavy weapons after several deaths35. Kwaku Dua then imposed a trade embargo on the British, blocking all the Asante roads to the south for the remainder of his reign while demanding that the criminals be extradited, a request that Richard Pine continued to reject despite the devastating loss of trade from Asante. Pine also responded to the blockade with his own blockade of ammunition supplies to the Asante36. The latter move that would have been devastating for Asante military had it not been for their continued access to firearms through the Dutch-controlled fort of Elmina which until the year 1868, continued to be loyal to the Asante, supplying the kingdom with over 18,000 flintlock rifles and 29,000 kegs of gunpowder between 1870 and 187237.

The British capture of Elmina and the war of 1874.

Between 1868-1873, the continued skirmishes between the British protected territories in the south-west and the Asante garrisons in the region, led to the British loss of several territories as Asante attempted a full occupation of the region,38 these battles eventually brought them near the fort of Elmina. The Dutch-owned fort of Elmina had been directly under Asante’s administration between 1811-1831, but the local edena chiefdom that controlled the lands around it had asserted its independence after the Asante army failed to protect it against an attack by British-allied chiefs from cape coast, but it nevertheless remained loyal to Asante as a check against its hostile neighbors, and every year the Dutch delivered an annual pavement to Kumase that most considered tribute/rent but that Elmina considered a token appreciation of the good Asante-Dutch trade relations. The Dutch eventually relinquished ownership of the Elmina fort to the British much to Asante's displeasure, this occurred after a lengthy period of negotiations between cape-coast and Elmina over their competing spheres of influence of the British and the Dutch, that had resulted in attacks by the British allies on Elmina and came at a time of a wider Dutch withdrawal from their African coastal possessions. The newly elected Asantehene Kofi Kakari (r 1867-74) realizing the threat this loss of Elmina presented, protested the transfer with a claim that the annual tribute paid to him by the Dutch gave him rights over the castle’s ownership39 but the transfer was nevertheless completed in 1872. The Asante assembly authorized the deployment of the military in the south western provinces in December 1872, and a large force of about 80,000 was mustered to pacify the south-western provinces and forcefully repossess the Elmina fort, this army had rapidly conquered most of the British protected provinces and made preparations to capture Elmina, but was withdrawn by September 1873 on orders of the council, and the Asante commander Amankwatia, was forced to to move his forces as well the Europeans he had captured back to Kumase despite his apparent victory.40 With the capture of Elmina, and the arms blockade, the British had cut off Asante’s source of firearms and undermined the ability of the Asante to play European arms-suppliers against each other. For over four centuries, this political strategy had excellently served African states, especially in west-central Africa where the Dutch were pitted against the Portuguese and in the sene-gambia where the French were pitted against the English.

The British, who were now intent on circumnavigating Asante control of the now-blocked cape-coast trade route, now had room to attack Kumase, and they mobilized their forces on an unprecedented scale after the government in London had appointed the cape coast captain Garnet Wolseley and provided him with £800,000 (over £96,000,000 today) as well as 2,500 British troops and several thousand west-Indian and African allied troops41. This force slowly proceeded north to Kumase where an indecisive council was repeatedly objecting to any attempts of mobilizing a counter-attack42perhaps recalling Richard Pine’s failed expedition a decade earlier, it was only after the British force reached the town of Amoafo about 50 km south of Kumase, that the Asante decided to counter-attack but even then the mobilization of troops and the battle plan was incoherent, rather than amassing at Amoafo, the forces were divided between several engagements and only about 10,000 Asante soldiers faced an equally matched British force. Once again, the Asante maintained a steady volley of musket fire using old flintlocks popular during the battle of waterloo in 1814, against the quick-firing enfield rifles and snider rifles of the British forces made in the 1860s of which the Asante had few, and despite holding the invaders for long, the cannon fire from the British won the day, forcing the Asante force to retreat after suffering nearly thousand causalities against less than a 100 on the British side, thus opening the road to Kumase, although the city itself had been deserted on Kofi's orders to deny the British a decisive victory. Aware of this, Wolseley blew up Kofi’s palace, sacked the city of Kumase and withdrew back to the coast but was met by Asante envoys enroute, who were sent by Kofi after another section of the British force had threatened Kumase following Wolseley's departure, these envoys agreed to sign a treaty where the Asante accepted to pay in installments an indemnity of 50,000 ounces of gold dust as well as to renounce claims to the south-western provinces.43 But the British victory was pyrrhic, Kumase was re-occupied by the King, and the Asante only paid about 2,000 of the 50,000 ounces, which couldn’t cover a fraction of the cost, Wolseley had little to show for his victory except the treaty.

Elmina castle.

Interlude: The Asante state from crisis to civil war (1874-1889)

By July of 1874, the Asantehene Kofi lost favor in the Kumasi council which proceeded to depose him after leveling charges against him that included not listing to counsel and incessant warfare; and although Kofi defended himself that the council supported his victories but blamed him for the destruction of Kumasi, he was later forced into exile and a reformist Asantehene Mensa Bonsu (1874-1883) was elected in his place. Mensa attempted a rapid modernization of Asante's institutions that was supported by prince Owusu Ansa after he had been emboldened by his crushing defeat of the British-allied province of Dwaben in 1875, but this attempt at reform came at a time of great political uncertainty with the Kumasi council not full behind him, and he was met with stiff opposition among some powerful officials44. Mensa’s disillusionment at his growing political isolation made him reverse many of his earlier flirtations with reform, he formed a personal-corps of 900 soldiers armed with modern snider rifles (after the arms embargo had been briefly lifted thanks to Owusu’s skilled diplomacy), these personal guards were directly under his control and brutally suppressed opposition in the capital, yet despite this, revolts now occurred in rapid succession close to Kumase by 1883 lasting a year until he was deposed by the council. between 1875 and 1890, most of the northern provinces rebelled against Asante control and broken away, importantly, the British now bypassed Kumase, allied with the eastern provinces of Asante and traded directly with the northern merchants of Salaga.45 In 1884 and Kwaku Dua was elected in his place but his reign was brief (17th march to 11th July 1884), and his death was followed by a period of internecine civil war as various factions unleashed during Mensa’s reign, sought to use force to influence the election/forcefully install their preferred Asantehenes, this weakening of the center led many of the provinces of Asante to breakaway.46

The Prempeh restoration, Asante’s diplomacy with several African states and the British (1889-1895).

Asante’s brief civil war ended with the election of Prempeh in 1888, the young king restored many of the lost provinces through skillful diplomacy and reignited the lucrative northern trade through Salaga by 1890, and the kingdom developed a lucrative trade in rubber, with over 2.6 million pounds exported in 1895, most of which was sold through the cape coast itself47. His rapid success alarmed the British at cape-coast and their coastal allies who now had to conduct their northern trade through Kumase, and were still intent on conquering Asante, therefore in 1891, the British demanded that it become a “protectorate”(where the kingdom’s external trade and foreign policy would be dictated by the British), an offer the Kumase council and Prempeh firmly rejected.48 On 1894, the British made even stronger demands for the Asante to be placed under “protectorate” status, demanding that a British officer be stationed at Kumase and he be consulted on matters of war and that the Asantehene and his councilors become paid servants of the British, this demand was again rejected.49

An even more threatening factor to the British was Prempeh's alliance with Samory Ture whose empire controlled vast swathes of territories in west-Africa from Senegal through guinea, ivory coast and Burkina Faso, and had conquered the breakaway region of Gyaman and its city of Bonduku in 1894 bringing him right next to the Asante border. Since the early 19th century, the Asante had made several diplomatic overtures to its northern and western neighbors such as the empire of Segu in 1824 and Dahomey in the 1870s, for a military alliance against the British but since the British supported Segu against the Hamdallaye empire, this first alliance didn't come to fruition, and the Dahomey alliance was rather ineffective. It therefore wasn't until the late 19th century that Samory's anti-French stance and the Asante's anti-British stance formed a loose basis for an anti-colonial alliance while simultaneously threatening both European powers, especially the British who felt that their position in west Africa was to come under French orbit in the event that the latter were to win against Samory. On 15th November 1895, the cape coast’s British governor warned Samory not to intervene on Asante's behalf as he was preparing to take Kumase under British control50. The British had eliminated the threat Samory posed by straining his ability to purchase munitions through sierra Leone that he was using against the French, and despite Samory's defeat of a French force in 189551. Despite Prempeh’s partial restoration of the pre-1874 Asante institutions, its military hadn’t been strengthened to its former might, given a depleted treasury, most of the Asante political focus relied on the diplomatic efforts of the Owusu Ansa and his large group of Asante envoys who were in London attempting to negotiate a treaty more favorable to Asante and to convince the colonial office against conquest, unfortunately however, the colonial office’s claim the the Asante wanted to ally with the French (an absurd claim given their flirtations with Samory), made the colonial secretary authorize a war with Asante, and the same ship that carried the ambassadors back to Asante from London also carried 100 tonnes of supplies for the kingdom’s conquest52.

The Fall of Asante in 1896.

The British force of over 10,000 armed with the Maxim guns and other quick-firing guns, occupied Kumase in January 1896 and were met with with no resistance after Prempeh had ordered his forces not to attack judging his forces to be too outgunned to put up an effective resistance, Kumase was thoroughly looted by the British and their allies, the Asante kingdom was placed under "protectorate" status and the Asantehene was forced into exile53. While the Asante state continued to exist in some form around Kumase, its political control over the provinces outside the capital had been effectively removed as these provinces were formally tributaries for the British, and despite the large armed uprising in 1900 based at Kumase, the Asante state as it was in the 19th century had ceased to exist.

Kumase in 1896 after its looting.

Asante's conflict with the British was directly linked to the latter’s desire to control trade between the west-African interior and the coast as well as the gold-mining in the Asante provinces, both of which were under the full control of Asante and formed the base of its economic and political autonomy, which it asserted through its strong control over its extensive road network. The Asante's monopolistic position in the transit trade between the savanna and the coast was weakened by the secessions after its 1874 defeat which fundamentally undermined the institutions of the state, and while this decline was arrested by Prempeh in the 1890s through skillful diplomacy that saw the restoration of the northern trade routes and attempts at military alliances, the reforms didn’t occur fast enough especially in the military, and Asante were thus unable to afford the means, whether in imported weaponry and skills or otherwise, to offset the effects of the progressive reduction in the general cost of imperial coercion in Africa which the western European industrial economies were experiencing through advances in military technology.

Conclusion: the evolution of Afro-European warfare from the 15th-19th century

From the 15th to mid 19th century, western military technology offered no real advantages in their wars with African armies, and this explains why so many of the early European wars with African states in this period ended with the former's defeat across the continent especially in west-central Africa and south-eastern Africa. European states opted to stay within their coastal enclaves after their string of defeats, aware of the high cost of coercion required to colonize and pacify African states, they were often dependent on the good offices of the adjacent African states inorder to carry out any profitable trade, and accepted the status of the junior partner in these exchange, in a coastal business that was marginal to the interior African economic system, as in the case of the Dutch traders at Elmina and or the Portuguese traders in Mutapa who were gives the title of "great-wives-of-state” after their failed conquest of the kingdom in the 17th century54.

But by the second half of the 19th century, the rapid advances in military technology such as the invention of quick-firing guns greatly reduced the cost of conquest both in numbers of soldiers and in ammunition. African states which had for long engaged the European traders from a stronger position of power and could pit European gun suppliers against each other, were now seen as an "obstacle" to trade rather than a senior partner in trade, and to this effect, the European coastal forts were turned into launch-pads for colonial conquest that in many places involved lengthy battles with African armies that lasted for much of the 19th century. While Asante had possessed the structural and demographic capacity to withstand the British attacks for nearly a century and the diplomatic know-how to navigate the rapidly changing political landscape both within Africa and Europe, the civil war of the 1880s greatly undermined its capacity to rapidly reform its military and political institutions, and tipped the scales in favor of the colonists, ending the Asante’s 300 year-old history.

Yam festival in Kumasi, 1817

HUGE THANKS to my Patreon subscribers and Paypal donors for supporting AfricanHistoryExtra!

Read more about the Asante’s road network and transport system, and Download books on the Anglo-Asante war on my Patreon account

The forest and Twis by Ivor Wilks pg 4-7)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 110),

Denkyira in the making of asante by T. C. McCASKIE pp 1-25)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 18-22)

State and Society in Pre-colonial Asante By T. C. McCaskie pg 146)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks 387-413)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 80-83, 94-95)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 678)

Warfare in Atlantic africa by J.K.Thornton pg 63-64

The Fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 66-69

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 683, 682)

Commercial Transitions and Abolition in West Africa pg 144-159

Accumulation wealth belief asante by T. C. McCaskie pg 26-27

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 683-695, Accumulation wealth belief asante by T. C. McCaskie pg 33, )

Commercial Transitions and Abolition in West Africa 1630–1860 By Angus E. Dalrymple-Smith pg 168-169

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks Pg 264-272)

Elmina and greater asante pg 39-41)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 163

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 141-151)

The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 21-22)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg pg 167)

From slave trade to legitimate commerce by Robin Law pg 107-110, additional commentary from “Commercial Transitions and Abolition in West Africa” pg 144-159

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 169-173),

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg pg 175),

The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 80)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 214, The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 44-48

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 180, The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 82)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks 183, The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 85)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 189-193)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 194)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 216-218)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 219-220)

The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 96)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 224)

The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 68

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks 225-228)

Elmina and Greater Asante by LW Yarak pg 33-46)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 235-238)

The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 124),

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 238-241)

The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 142-170)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 512-528, 627-230)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 280-281

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 558-567)

The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 181

The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 180-194)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 639-640

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 301-304, 310-324)

A Military History of Africa [3 volumes] By Timothy J. Stapleton pg 22)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 653

The fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton pg 184

Portugal and Africa By D. Birmingham pg 16

As always a great read and great info keep it up brotha btw, I don't know if you do requests if I'm being too pushy or anything I apologize and if it's not too much I was wondering if perhaps you could maybe do a sort of research page on Warrior type classes in Africa. For example we know about Vikings and Knights and Samurai but perhaps the equivalent of sorts in Africa would be interesting if you have the time or want to.