An African civilization in the heart of the Sahara: the Kawar oasis-towns from 850-1913

castles, salt and dates

The central Sahara may be the world's most inhospitable environment, but it was also home to one west Africa's most dynamic civilizations.

The picturesque oases of Kawar in northern Niger; with their towering fortresses, multi-colored salt-pans and shady palm-gardens, were at the heart of west Africa's political and economic history, facilitating the production and exchange of commodities that were central to the urban industries of the regions' kingdoms.

This article explores the history of the Kawar oasis towns from the 9th century, it includes an overview of the production and trade of salt in Kawar and the role of its oasis-towns in the political and economic history of the central Sahara.

Map showing the Kawar Oases1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Description of Kawar and its early history: 850-1050

Kawar comprises a 80-km series of fortified Oasis towns in north-eastern Niger, on the eastern edge of the Ténéré desert. From the north, the string of Oasis towns begins with the Djado cluster, that includes the towns of; Djaba, Djado, Chifra and Seguedine, which were occupied as early as the 11th-14th century based on material recovered from Djaba. Settlements comprise agglomerated stone and mudbrick structures, as well as fortresses with square towers, date-palm gardens, wells. The main towns of Kawar are located just south of this Djado cluster, and they include the towns of Aney, Gazebi/Gasabi, Emi Tchouma, Dirku, Bilma, Fachi, and Agadem. These settlements comprise substantial rectilinear stone and mud-brick structures, large square fortresses, mosques, date-palm gardens, wells and salt-pans.2

The role of Kawar in the trans-Saharan trade was well known in the medieval sources from the 9th century and local sources from the 16th century; the main towns at that period were Gasabi, Bilma, and Djado. The town of Gasabi was among the oldest settlements in Kawar and is the largest of them, covering 320 acres including the 20ha town itself and 300 acres of gardens. Tradition of its original inhabitants called the Gezebida —who now reside in the towns of Aney and Emi Tchouma— claim that the town was surrounded by a perimeter wall and that it was conquered by the Tebu/Teda after a long battle.3 Kawar was first documented by Ibn Abd al-Hakam the 9th century and is associated with the north African conquest of the Rashidun general Uqba b. Nāfi in the 7th century, who reportedly seized its main citadel (although this may be anachronistic)4. The Kawar towns of Gasabi and Bilma were first mentioned by al-Muhallabi (d. 963) as the major Oasis towns which travelers went through to reach the kingdom of Kanem in the lake chad basin, its likely that Gasabi was originally inhabited by Ibadis.5

In the mid 12th century, the geographer Al-idrisi provided the most detailed description of the Kawar oasis towns; Qaşr Umm Īsā (Djado?) and al-Qaşaba (Gasabi) with their “date-palms and wells of sweet water” as well as the production and export of a mineral called "shabb" from the salt-mining oasis towns of Kawwār to markets in Egypt and in the maghreb, which was said to be without equal in quality6. He also identifies the Kawar town of Ankalās (Kalala) —which he located south of Gasabi and north of Tamalma (Bilma)— that reportedly had mines of pure shabb, that was gathered from the mountains. Al-idrisi's “shabb” may relate to Kawar’s alum trade which was directed towards north Africa, but he may have combined it with the large scale of salt-mining from Kawar oases.7

ruins of Djado surrounded by date-palm trees

Djaba

ruins of Dabassa (Chirfa) and Séguédine

ruins of Bilma

Kawar under the Kanem-Bornu empire: 1050-1759

The inhabitants of Kawar consist mainly of the Tebu, who are more closely connected to the highlands of Tibesti in northern chad, and the Kanuri, who are associated with the empire of Kanem and Bornu. The Kanuri are the older part of the population that's associated with the earliest settlements, and the part that is most closely connected to the salt production, they were likely contemporaneous with the foundation of the oldest towns during the time when the Ibādīs were active in the central sahara.8 The earliest traditions associating the Kanem empire with the Kawar oasis towns was during the reign of the Kanem emperor (Mai) Arku (r 1023-1067) whose mother was said to have been born in Kawar. Arku is credited with the establishment of Kanuri settlers in the region of Kawar from Dirku to Séguédine, but this settlement may have been short-lived since Kawar is mentioned to be under an independent king according to al-Idrisi (d. 1165).9

It was during the reign of Mai Dunama Dibalami (1210-1248) that Kanem firmly extended its control over the oasis towns of Kawar as part of its northward conquest of the Fezzan (southern Libya) where the Kanem ruler established his provincial capital at Traghen. The Kanem control of southern and central Libya lasted over two centuries and its attested in external accounts by Ibn Sa'id (d. 1286) and al-Umari (d. 1384) who mentioned that Kanem’s political influence extended to the town of Zella, a few hundred kilometers south of Libya’s coast10. The Kanuri legacy in southern and central Libya remains visible with the ruins of Kanem cities such as Traghen, the use of Kanuri wells in various oases towns of southern Libya, and the population of Kanuri speakers.11

Read more about the Kanem-Bornu conquest of Libya on Patreon:

Kawar-type oasis communities of the Kanuri extended further northwards during this period, for example, just south of Traghen is the fortified oasis town of Ganderma built in the same fashion as the Kawar oasis towns. The town contains many old wells built during the Kanem era, which still bear their original Kanuri names as recorded by Nachtigal in the mid-19th century, suggesting that Ganderma represented one of the old settlements of the Kanuri in southern Libya.12 While the oasis towns of Kawar were located along an important trans-Saharan trading route, few appear to have been dependent on the commercial and political conditions of this trade, as the basis of their existence was entirely concerned with the exploitation of Salt. In the 15th century, only one of the oasis towns; Gasabi, was known for trade, while the rest of the towns, especially Bilma and Dirku were exclusively associated with the salt and alum trade.13

The Tebu who presently form a local political elite in Kawar, arrived in the area around the 15th-17th century from the Tibesti region of northern Chad14. The nominal ruler of the entire Kawar was always a Tebu, and some of the oasis towns such as Dirku were occasionally considered "capitals" of Kawar, and were the residence of a tomagra chief, a title held by Tebu rulers who were connected to the Tibesti region, that also used Kawar as a halting station on the route from Bornu through Murzuq to Tripoli15. The Gezebida who previously inhabited the town of Gasabi and are now settled in the northernmost oasis towns of Ayer and Emi Tchouma, are products of the intermarriage between the Kanuri and Tebu.16

Map showing the migrations from the Tibesti region between the 13th and 19th century17

The political relationship between the Tebu and Kanuri was however more fluid than the hierarchical one of Kanem. For example, the town of Séguédine appears to have remained under local Kanuri control even after the Tebu’s arrival, with a chief bearing the title 'Mai' Gari. Similarly, the cluster of towns from Djado to Djaba were settled entirely by the Kanuri and were more connected to the town of Fachi than other Kawar towns, with the Kanuri community at Djado lasting until the mid-19th century when the town became a majority Tebu settlement.18 Additionally, despite the use of the Tebu title of tomagra by the elites at Dirku, the town's ruling class (called the Tura) claimed to be clan from Bornu in the eastern shores of lake Chad (where the Kanem rulers eventually re-located), and the rulers of Kawar’s other towns including Bilma, often carried the title of Mai, claiming to be subjects of Bornu.19

Re-established in the 15th century on the western shores of lake Chad, the empire of Bornu retook Kawar during the reign of Mai Ali Gaji before 1500, who took the town of Fachi.20 The Bornu conquest of Kawar was continued by Idris Aloma who conducted expeditions into several oasis towns especially Fachi and Bilma, forcing the local Tubu elite to seek refuge in the surrounding regions, but most of them eventually submitted to Bornu's rule such as the rulers of Djado who sent a delegation to Mai Idris. While Gasabi isn't treated as target of Idris' campaigns, it was nevertheless included among the other Kawar towns (along with Bilma and Dirku) that brought horses to the king of Bornu. The salt trade from Kawar was thereafter oriented towards the Bornu region where it was traded southwards to the Hausalands and other parts of west Africa.21

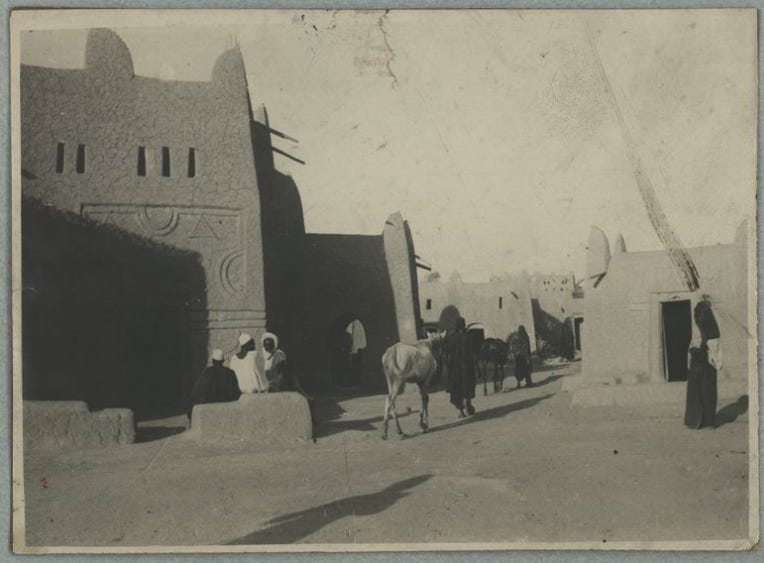

Séguédine

Djado

Dirku

Fortresses of Fachi, and Aney

Kawar under Tuareg rule from 18th-19th century; Salt production and trade in the central Sudan

Beginning in the early 18th century, the decline of Bornu's military strength led to its loss of the Kawar region to the forces of the Tuareg especially after the battle of Ashegur that was fought near the town of Fachi in 1759-176022. The Tuareg then established their own political system over Kawar, which was controlled through the office of an appointed figure called the Bulama, and they then shifted the Kawar salt trade through their territories. The Tuareg possessed a less centralized/hierarchical political structure than Bornu, as they constituted independent segments/clans that recognized the authority of a nominal king (Amenokal) who was based at Agadez. In Kawar, the most prominent Tuareg clan were the Kel Owey; their activities there were almost entirely confined to the lucrative salt trade which they funneled through Agadez and the Hausa cities.23

It is during the 18th and 19th century when we get a more complete description of the structure of salt production and trade from Kawar. The individual owners of salt pits in Kawar often went to the local chieftain to receive permission to dig them, and in exchange paid a duty/tax, but the individuals could transfer or sell their salt-pits at will. The majority of the owners of salt-pits and their workers were Kanuri, but some included the Teda, and the average Kanuri owned anywhere between 4 to 20 salt pits. In theory, the salt pits and the surrounding land belonged to the local chieftains (and to their Bornu and Tuareg suzerains) but this was largely formal rather than practical. Each salt-basin owner paid a small tax to the local chieftain, the latter of whom then remitted it to the Bulama, whose then passes it on to his counterpart on the Tuareg side; the Sarkin Turawa (who represents the king of Agadez) and who also received the duty at the beginning of each caravan.24

The vast majority of those who worked the salt pits of Kawar were free and were the owners of their own pits, rather than enslaved people who had been brought to work the mines —as earlier scholarship had wrongly surmised—25. The bulk of the salt-mining labor was supplied by other family members but in the case of wealthy mine owners, this was supplemented by wage-laborers paid in salt. While slaves formed a minority of the population in the Oasis towns and weren't needed for salt production but for mostly domestic activities, wealthy salt-pit owners would occasionally include slave labor in salt mining and these were paid half the wages of the wage laborers.26

The technique of salt production is based on the evaporation of subsoil water that has passed through layers of salt and is collected in pits dugs to a depth of 2 meters and a breadth of 20-25 sqm. Different layers of salt are formed of varying quality after a number of weeks, and the process required little human assistance making the work generally non-intensive. The best quality salt were called beza, which are shaped into salt-cakes of 4-6kg while the coarser ones are called kantu, which are blocks of 15-20kg, with a single salt-pit producing around 4-5 tonnes each season, or about 40-50 camel loads of salt. An average of 30,000 camels a year are estimated to have carried 2-3,000 tonnes of salt a year during the 19th century from the salt-mines of Kawar, which was just under a third of Bornu's annual production of 6-9,000 tonnes.27 The oases of also produced red natron especially at Dirku, while white natron was taken from Djado and Séguédine.28

Besides salt, the other source of wealth in Kawar was date-palms. Gardens of dates were first mentioned in the 9th century and there are 100,000 of these by the mid 20th century, many of these dates are of high quality and are sold regionally in the Saharan region of Aïr (where the Tuareg are centered), and unlike the Kanuri dominated salt-production, the growing and sale of dates also involved the Tebu.29

Saltpans of Bilma

date-palms of Djado

Trading was conducted between the Kanuri and the Tuareg through client relationships overseen by the Bulama and the Sarkin Turawa, during the two main trading seasons of the year when caravans arrived at Kawar. The salt was often exchanged for grain, livestock and pastoral products at relatively fixed prices and the grain was often stored in Agram for resale throughout the Oasis towns, the salt was also exchange for textiles and other commodity currencies used in long distance trade. Since the 18th century, much of the southwards trade was controlled by the Tuareg who were involved in the regional trade for grain grown in various Sahelian cities where large farms owned by Kanuri and Hausa merchants produced the primary grain demanded in Kawar. One wealthy merchant in the Kanuri city of Zinder (kingdom of Damagaram) was Malam Yaro, the son of a Kanuri merchant and a Tuareg woman, who invested in the salt and grain trade between the Tuareg and Kawar and built up a large-scale business from west Africa to north Africa.30

Malam Yaro’s house in Timbuktu (left), 1930, quai branly

The salt from Kawar was used for a variety of industrial, culinary, medicinal purposes. The main function of salt besides its consumption by people and livestock was; as a mordant in dyeing textiles; in the making of soap and ink; in the leather industry for tanning hides and skins; and in treating various medical ailments. Kawar’s natron had a high demand in Hausa city-states especially prior to the 19th century when textile dyeing required the use of white natron, and in the Bornu and Hausa markets where leather trade was a significant crafts industry.31

The grain and other agricultural products received in exchange for Kawar's salt enabled the Oasis towns to sustain relatively large populations that would otherwise be impossible to maintain in the arid environment.32

abandoned houses in Fachi

abandoned houses in Djado

Kawar from the Ottoman and Sannusiya era to French colonialism; 1870-1913

By the mid-19th century, the Ottoman conquest of the Fezzan region (southern Libya) forced the its local elite; the Awlad Sulaiman, out of their capital at Murquk and into the Kawar and Tibesti regions where they took to raiding trade caravans and caused a general state of insecurity in the region. The Kel Owey provided little military assistance to the inhabitants of Kawar against these raids, so the latter's local rulers sought the aid of the Ottomans who flushed out the Awlad Sulaiman brigands by 1871. In response to the Kel Owey's apathy, the Kawar elite sent more requests to the Ottomans in the 1875 and 1890 to formally occupy Kawar, but these were not fulfilled until 1901, by which time, the rulers of Kawar had switched their allegiance to the Sanussiya brotherhood.33

The Sanussiya were the main political and commercial organization of the central Sahara in the late 19th century, and had attracted many Tebu and Kanuri from Kawar as initiates, constructing lodges in Djado and Bilma between the 1866 and the 1890s34. However, Kawar never become as important to their activities as other regions (such as Wadai), especially considering the French advance from the south. Beginning in 1906, French forces gradually occupied the towns of Kawar, meeting little resistance until Djado where a number of skirmishes were fought beginning in 1907 and ending with the French occupation of the town in 1913.35

While some of the Kawar oases like Bilma and Dirku remained important centers of salt and natron production, the rest of the towns such as Djado were abandoned in the mid-20th century, their ruins gradually covered by the shifting sands of the Sahara.

Djaba in winter

As the example of Kawar has shown, the Sahara desert wasn’t an impenetrable barrier that divided Africa. During the ancient times; Africans travelled and lived in the Roman Europe just as Romans travelled into Africa; read about this and more in;

On Kanem-Bornu’s conquest of southern and central Libya;

If you liked this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal/Ko-fi

taken from; l-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond by Martin Sterry, David J. Mattingly

Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond by Martin Sterry, David J. Mattingly pg 303-304, 305-306

Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 21)

The Oasis of Salt: The History of Kawar, a Saharan Centre of Salt Production Knut S. Vikør pg 150

Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 22, Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 161

The Oasis of Salt: The History of Kawar, a Saharan Centre of Salt Production Knut S. Vikør pg 295, 169

The Desert-Side Salt Trade of Kawar by Knut S. Vikør pg 123-5, Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 28, 33)

The Desert-Side Salt Trade of Kawar by Knut S. Vikør pg 115, Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 36, The Oasis of Salt: The History of Kawar by Knut S. Vikør pg 161-163, 169

Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 37)

The kingdoms and peoples of Chad by Dierk Lange pg 252

Kanem, Bornu, and the Fazzān: Notes on the political history of a Trade Route by B. G. Martin

Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 31-32)

Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 32-33)

The Oasis of Salt: The History of Kawar, a Saharan Centre of Salt Production by Knut S. Vikør pg 50,63

Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 23, 29, An Episode of Saharan Rivalry: The French Occupation of Kawar, 1906 by Knut S. Vikor pg 702)

Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 37)

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 178

The Oasis of Salt: The History of Kawar, a Saharan Centre of Salt Production by Knut S. Vikør pg 59)

The Oasis of Salt: The History of Kawar, a Saharan Centre of Salt Production by Knut S. Vikør 190, An Episode of Saharan Rivalry: The French Occupation of Kawar, 1906 by Knut S. Vikor pg 702)

The Oasis of Salt: The History of Kawar, a Saharan Centre of Salt Production by Knut S. Vikør pg 188)

Al-Qasaba et d'autres villes de la route centrale du Sahara by Dierk Lange and Silvio Berthoud pg 38-39, Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 275

The Oasis of Salt: The History of Kawar, a Saharan Centre of Salt Production by Knut S. Vikør pg 212

An Episode of Saharan Rivalry: The French Occupation of Kawar, 1906 by Knut S. Vikor pg 702-703)

The Desert-Side Salt Trade of Kawar by Knut S. Vikør pg 118)

The Desert-Side Salt Trade of Kawar by Knut S. Vikør pg 118, The Oasis of Salt: The History of Kawar, a Saharan Centre of Salt Production by Knut S. Vikør pg 91

The Desert-Side Salt Trade of Kawar by Knut S. Vikør pg 118-120)

The Desert-Side Salt Trade of Kawar by Knut S. Vikør pg 122, 135, The Borno salt industry by P. Lovejoy pg 639

The Borno salt industry by P. Lovejoy pg 630

The Oasis of Salt: The History of Kawar, a Saharan Centre of Salt Production by Knut S. Vikør pg 34-233

The Desert-Side Salt Trade of Kawar by Knut S. Vikør pg 127-128, 139

The Borno salt industry by P. Lovejoy pg 635-636

The Desert-Side Salt Trade of Kawar by Knut S. Vikør pg 139,

An Episode of Saharan Rivalry: The French Occupation of Kawar, 1906 by Knut S. Vikor pg 704-712

Libya, Chad and the Central Sahara By John Wright pg 92-94

An Episode of Saharan Rivalry: The French Occupation of Kawar, 1906 by Knut S. Vikor pg 712-714)

Amazing article,it’s crazy how these town settlements have been mystified and has had it’s origins being attributed to Berbers and foreign entities

The history of the Sahara desert is still so interesting to me, and I'm glad you mentioned the fact that the Sahara was never a barrier between the Southern nations and more Northerly regions but instead a sort of bridge that many African peoples would traverse back n forth through since it's greener phase up till now.