Kilwa, the complete chronological history of an East-African emporium: 800-1842.

Journal of African Cities chapter-2

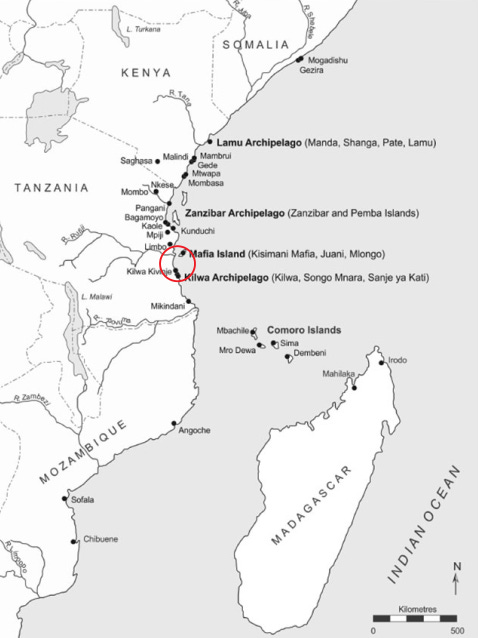

The small island of Kilwa kisiwani, located off the coast of southern Tanzania, was once home to one of the grandest cities of medieval Africa and the Indian ocean world. The city-state of Kilwa was one of several hundred monumental, cosmopolitan urban settlements along the East African coast collectively known as the Swahili civilization.

Kilwa's historiography is often organized in a fragmentary way, with different studies focusing on specific eras in its history, leaving an incomplete picture about the city-state's history from its earliest settlement to the modern era.

This article outlines the entire history of Kilwa, chronologically ordered from its oldest settlement in 7th century to its abandonment in 1842. It includes all archeological and textual information on Kilwa's political history, its major landmarks, its material culture, its economic history, and its intellectual production.

Map showing some of the Swahili cities of the east African coast, the red circle includes the archipelagos of Kilwa and Mafia which were under the control of Kilwa's rulers.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early Kilwa (7th-11th century)

The site of Kilwa kisiwani was first settled between the 7th-9th century by the Swahili; a north-east coastal Bantu-speaking group which was part of a larger population drift from the African mainland which had arrived on the east African coast at the turn of the common era.1 Their establishment at Kilwa occurred slightly later than the earlier Swahili settlement at Unguja, but was contemporaneous with other early settlements at Manda, Tumbe and Shanga (7th-8th century). The early settlement at Kilwa was a fishing and farming community, consisting of a few earthen houses, with little imported ceramics (about 0.7%) compared to the locally produced wares.2

While the exact nature of the early settlement is still uncertain, it was largely similar with other Swahili settlements especially in its marginal participation in maritime trade and gradual adoption of Islam. Its material culture includes the ubiquitous early-tana-tradition ceramics which are attested across the entire coast3, and a relative large amount of iron slag from local smelting activities4. Iron made in Kilwa (and the Swahili cities in general) is likely to have been exported in exchange for the foreign goods, as it was considered a highly valued commodity in Indian ocean trade.5

Map of Kilwa and neighboring island-settlements6

Classical Kilwa (12th-15th century)

Like most of its Swahili peers, Kilwa underwent a political and economic fluorescence during the 11th century, with increased maritime trade and importation of foreign (Chinese and Islamic) ceramics, local crafts production especially in textiles, and the advent of substantial construction in coral; which at Kilwa was mostly confined to the reconstruction of the (formerly wooden) Great mosque as well as the construction of coral tombs. This transformation heralded the ascendance of Kilwa's first attested ruler (sultan) named Ali bin al-Hassan, whose reign is mostly known from his silver coins, tentatively dated to the late 11th century. 7

kiln for making lime cement used to bind the dry blocks of coral-rag , in southern Tanzania. Porites coral on the other hand, is often carved while still soft and wet. This lime-making process is described at Kilwa in a 16th century account.8

Al-Hassan is identified in latter accounts as one of the "shirazi" sultans of Kilwa. The ubiquitous "shirazi" epithet in Swahili social history, is now understood as an endonymous identification that means "the Swahili par excellence" in opposition to the later, foreign newcomers; against whom the Swahili asserted their ancient claims of residence in the cities, and enhanced their Islamic pedigree through superficial connections to the famous ancient Persian city of shiraz that is located in the Muslim heartlands.9

Kilwa first appears in external accounts around the early 13th century, in which the city is referred to simply as "a town in the country of the Zanj" in the account of Yaqut written in 1222.10 . In the late 13th and early 14th century, Kilwa extended its control to the neighboring islands of the Mafia archipelago including the towns of Kisimani mafia and Kua11, becoming the dominant power over much of the southern Swahili coast. Kilwa also seized sofala from Mogadishu in the late 13th century and prospered on re-exporting gold that was ultimately derived form the Zimbabwe plateau.12

During the late 13th century, Kilwa’s first dynasty was deposed by the a new dynasty from the nearby Swahili city of Tumbatu led by al-Hassan Ibn Talut, who founded the "Mahdali" dynasty of Kilwa. Tumbatu had been a major urban settlement on the Zanzibar island, its extensive ruins of houses and mosques are dated to the 12th and 13th century, and it appears in Yaqut's 1220 account as the seat of the Zanj. The city was later abandoned after a violent episode around 1350.13

The new dynasty of Kilwa may have had commercial ties with the Rasulid dynasty of Yemen although this connection would have been distant as Mahdali, who were most likely Swahili in origin, would have been established on Tumbatu and Mafia centuries prior to their takeover of Kilwa14. The most illustrious ruler of this line was the sultan al-Hassan bin sulayman who reigned in the early 14th century (between 1315-1355). Sulayman was a pious ruler who sought to integrate Kilwa into the mainstream Islamic world, prior to his ascendance to the throne, he had embarked on a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1331 and spent some time studying in the city of Aden.15

Sulayman issued trimetallic coinage (with the only gold coins struck along the coast), he built the gigantic ornate palatial edifice of Husuni Kubwa that remained incomplete, expanded the great mosque, and hosted the famous Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta. In his description of Kilwa, Ibn Battuta writes that;

"After one night in Mombasa, we sailed on to Kilwa, a large city on the coast whose inhabitants are black A merchant told me that a fortnight's sail beyond Kilwa lies Sofala, where gold is brought from a place a month's journey inland called yufi"

Battuta adds that Kilwa was elegantly built entirely with timber and the inhabitants were Zanj (Swahili), some of whom had facial scarifications.16

Kilwa declined in the second half of the 14th century, possibly due to the collapsing gold prices on the world market as well as the bubonic plague that was spreading across the Indian ocean littoral at the time. This coincided with the collapse of the recently built domed extension of the Great Mosque late in sulayman's reign (or shortly after) and the mosque wasn't rebuilt until the early 15th century.17

The decline of Kilwa may only be apparent, as it was during the late 14th century when the settlement on the nearby island of Songo Mnara was established. Songo Mnara was constructed over a short period of time, on a site with no evidence of prior settlement, its occupation was immediately followed by an intense period of building activity that surpassed Kilwa in quality of domestic architecture. The ruins of more than forty houses, six mosques and hundreds of graves and tombs are well preserved and were likely built during a short period perhaps lasting less than half a century.18

Kilwa recovered in the early 15th century with heavy investment in coral building around the city as well as the restoration of the Great mosque. This recovery coincides with accounts documented later in the 16th century Kilwa chronicle, in which political power and wealth in early 15th century Kilwa became increasingly decentralized with the emergence of an oligarchic council made up of both non-royal patricians and lesser royals, as well as the 'amir' (a governor with both administrative and military power) who wrestled power away from the sultan. By the late 15th century, the amir was Kiwab bin Muhammad, he installed a puppet sultan and centralized power around his own office, but his rule was challenged by the other patricians including a non-royal figure named Mohamed Ancony who was likely the treasurer. Kiwab was succeeded by his son Ibrāhīm Sulaymān who appears as the 'king of kilwa' in external accounts, and was in power when the Portuguese fleet of Vasco Da Gama arrived in 1502, although his actual power was much less than the title suggested.19

Map of 13th–14th-century ruins at Kilwa20, discussed below

Architectural landmarks from the classical Kilwa

The Great mosque of Kilwa.

The main Friday mosque of Kilwa is the largest among its Swahili peers. The original mosque was a daub and timber structure constructed in the late 1st millennium, and modified on several occasions. In the 11th century, flat-roofed (porites) coral mosque supported by polygonal wooden pillars, was constructed over the first mosque, and was occasionally repaired and its walls modified to maintain its structural soundness. During the early 14th century, the mosque was greatly extended and a new roof was constructed, supported by monolithic (porites) coral pillars, as well as by a series of domes and barrel-vaults, but these proved structurally unsound and collapsed. In the early 15th century, the pillars were constructed using octagonal coral-rag pillars, that were bounded with lime (already in use since the earliest constructions).21

Just south of the mosque is the Great House, a complex of three houses that were built in the 15th century and likely served as the new palace of the sultan after the abandonment of Husuni Kubwa. This house contained several courtyards, and a number of ornamental features such as niches and inlaid bowls in the plasterwork. A similarly-built "house of the mosque" was constructed nearby, as well as a small domed mosque, all of which are dated to the 15th century.22

The great mosque of Kilwa, ruins and ground plan23

The Small Domed Mosque, ruins and floor plan

Husuni Ndogo fortress.

This defensive construction was built in the 13th century, it is flanked by several polygonal and circular towers, the walls are currently 2m high and 1.2m thick with many buttresses about 1.8m long. The creation of a fortified palace serving as a caravanserai was likely associated with the increasing trade, around the time Kilwa had seized control of Sofala. Husuni Ndogo was abandoned following the construction of Husuni Kubwa.24

Ruins of Husuni Ndogo.

Husuni Kubwa

The palace of Husuni Kubwa was built in the early 14th century over a relatively short period and wasn't completed. The grand architectural complex consists of two main sections, the first of which is the palace itself which features the characteristic sunken courtyards and niched walls of Swahili architecture, as well as novel features such as arcaded aisles and an ornate octagonal pool. The Place roof was adorned with a series of fluted cones and barrel vaults built in the same style as the Great mosque. The second section of the complex was attached to the southern end of the palace, its essentially an open-air yard with dozens of rooms along its sides.25

Ruins of the Husuni Kubwa Palace and ground plan

Artificial causeway platforms built with cemented pieces of reef coral and limestone were constructed near the entrance to the Kilwa harbor between the 13th and 16th centuries. These served several functions including aiding navigation by limiting risk of shipwrecks, as walkways for fishing activities in the lagoons, and for ceremonial and ostentatious purposes that enhanced the city's status as a maritime trade hub.26

Causeway II in Mvinje Lagoon, Kilwa, and a Map of Causeways along the coast of Kilwa Kisiwani27

Songo Mnara was built on an island less than 20km away from Kilwa. Its occupation is dated between 1375 and 1500, with most of the construction occurring in the last quarter of the 14th century. The ruins comprise of several coral houses and mosques organized with a form of city plan that is flanked by open spaces and confined within a city wall. The two large structures sometimes referred to as ‘palaces,’ are actually sprawling composite buildings of multiple houses, and likely represent the wealthiest patricians/families in the town, which is unlikely to have had a single ruler.28

Ruins at Songo Mnara and a Map showing their general layout

Tombstone of princess Aisha of Kilwa, c. 1360 (Ethnologies museum, berlin)29

Kilwa coinage from the classical era.

Coins had been minted on the Swahili coast since the 8th century at Shanga, and coin mints continued to flourish during the classical Swahili era across several cities including at Unguja, Tumbatu, Pemba and Manda, but it was at Kilwa was minting was carried out on a monumental scale.30

Kilwa's locally minted coinage was made primarily of copper, with occasional issues in gold and silver. The coins were marked with the names of the Kilwa sultans, and decorated with rhyming couplets in Arabic script. The coins are variably distributed reflecting their different uses in local and regional contexts, with the majority copper coins being found in the immediate vicinity of Kilwa, Songo Mnara, Mafia, (and Great Zimbabwe), while the silver coins found on Pemba Island, and the gold coins were found in Zanzibar.31

The Mtambwe Mkuu hoard of silver coins from pempa island, made in Kilwa

Songo mnara hoard of copper coins made in Kilwa

Despite the dynastic changes recounted in Kilwa's history, no coins were withdrawn from circulation before the early 16th century, and the coins of earlier sultans are as likely to be attested across all hoards as those of the later sultans; likely because the latter sultans attimes continued to issue new coins with names of earlier sultans as well as their own, which may complicate dating.32

Kilwa's coinage was mostly local in its realization and differed from the Indian ocean coinage in a number of aspects. The copper coins of Kilwa weren't standardized by weight nor did they derive most of their value from a conversion value to other "higher metals" of gold and silver, but derived their value from their symbolic legitimating aspects associated with each ruler, as well as functional purposes as currency in local and regional trade.33

gold coins of Kilwa sultan al-Hassan Sulayman from the 14th century

The Portuguese episode in Kilwa’s history; documenting a crisis of legitimacy.

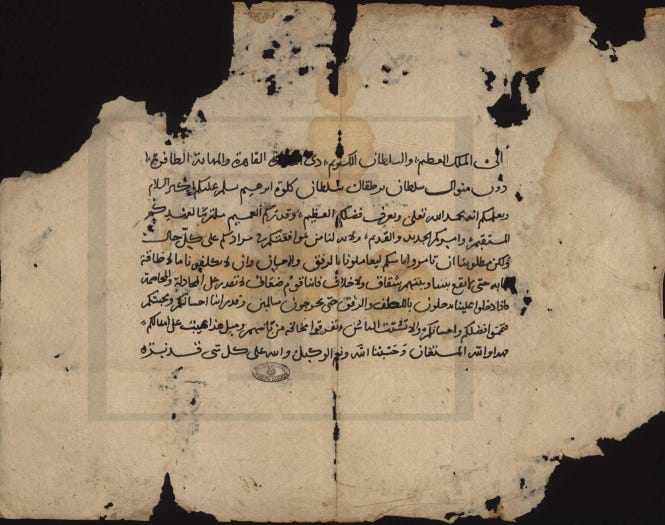

In 1505 Kilwa was sacked by the Portuguese fleet of Francisco de Almeida who invaded the city with 200 soldiers in order to enforce a botched treaty, signed between the reigning sultan Ibrāhīm Sulaymān and an earlier Portuguese fleet led by Vasco Da Gama in 1502. This invasion ended with the installation of a puppet sultan Mohamed Ancony who was quickly deposed due to local rebellion and for the succeeding 7 years the Portuguese struggled to maintain their occupation of the city, installing Ancony’s son (Haj Hassan) and later deposing him in favor of another figure, until 1512 when they conceded to leave sultan Ibrahim in charge. It was within the context of this succession crisis that the two chronicles of Kilwa's history were rendered into writing; both the Crônica de Kilwa and the Kitab al-Sulwa ft akhbar Kilwa, both written in the mid-16th century. 34 Atleast two letters addressed to the Portuguese were written by two of the important Kilwa elites who were involved in this conflict and are inlcuded below.35

The Chronicles recount the dynastic succession of a series of Shirazi and later Mahdali sultans in relation to the rise and fall of the city’s fortunes prior to, and leading upto the Portuguese episode. The Chronicles don't relate the true course of events in the settlement and political history of the city-state, they instead describe the urban and Islamic character of the settlement in relation to (and opposition against) its hinterland at the time when they were written.36

Letter by Sultan Ibrahim of Kilwa written in 1505, requesting the Portuguese king to order his deputy not to attack Kilwa. (Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo)

Letter written by Mohamed Ancony’s son Haj Hasan around 1506, complaining about his deposition by his erstwhile allies (Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo)

Kilwa in decline; reorientation of trade and the Portuguese colonial era. (1505-1698)

After their occupation of Sofala in 1505 and meddling in Kilwa's politics, the Portuguese interlopers had effectively broken the commercial circuit established by Kilwa which funneled the gold purchased from Sofala into the Indian Ocean world. Kilwa tried to salvage its fortunes in the mid-16th century by reorienting its trade towards its own hinterland, from where it derived ivory which it then sold to the Portuguese and other Indian ocean buyers in lieu of gold, and the city was reportedly still in control of the Mafia islands in 1571.37

In 1588, Kilwa was attacked by the enigmatic Zimba forces, an offshoot of the Maravi kingdom from northern Mozambique that had been active in the gold and ivory trade which had since been taken over by the Portuguese. The city had gradually recovered from this devastation by the 1590s as the Yao; new group of Ivory traders from the mainland, created a direct route to Kilwa from the region north of Lake Malawi.38

Succession crises plagued Kilwa's throne in the 1610s; and were instigated largely by interventions of the Portuguese, who had effectively colonized the Swahili coast by then and had re-occupied a small fort they constructed in Kilwa in 1505. The Portuguese eventually managed to placate the rivaling factions by channeling the ivory trade exclusively through Kilwa's merchants by 1635, thus maintaining their control of the city despite an Omani attack in 1652, as the city wouldn't revert to local authority until 1698 when the Portuguese were finally expelled from Mombasa.39

Old Portuguese watchtower, Kilwa (SMB, Berlin). the only surviving section of their original Gereza fort that was reconstructed by the Omanis in the 19th century

Recovery in the 18th century and Omani occupation in the 19th century.

Despite the reorientation of trade, Kilwa was impoverished under Portuguese rule and no buildings were constructed throughout the 17th century. The city's prosperity was restored in the early 18th century, under sultan Alawi and the queen (regent) Fatima bint Muhammad's reign, largely due to the expanding ivory trade with the Yao that had been redirected from the Portuguese at Mozambique island. This Kilwa dynasty with its characteristic ‘al-shiraz’ nisba like the classical rulers, frequently traded and corresponded with the Portuguese to form an alliance against the Omani Arabs, the latter of whose rule they were strongly against.40

letters written by Mfalme Fatima (queen of kilwa), her daughter Mwana Nakisa; and Fatima's brothers Muhammad Yusuf & Ibrahim Yusuf. written in 1711 (Goa archive, SOAS london)

In the early 18th century, Kilwa's rulers built a large, fortified palace known as Makutani, it engulfed the earlier ruins of the “House of the Mosque”, they also repaired parts of the Great Mosque. Kilwa’s influence also included towns on Mafia island especially at Kua where a large palace was built by a local ruler around the same time. They also reconstructed the 'Malindi mosque' which had been built in the 15th century, this mosque is associated with a prominent family from the city of Malindi (in Kenya) which rose to prominence at the court of Kilwa in the 15th century. An 18th century inscription taken from the nearby tombs commemorates a member of the Malindi family.41

Makutani Palace and plan of principle features.

Malindi mosque and cemetery

Epilogue: Omani influence from 1800-1842.

Kilwa increasingly came under Omani suzerainty in the early 19th century as succession crises and a conflict with the neighboring town of Kilwa Kivinje provided an opportunity for Sayyid Sa‘id to intervene in local politics. The Gereza fort built by the Omanis in 1800 is the only surviving foreign construction among the Kilwa ruins, the imposing fort had two round towers at diagonally opposed corners serving as platforms for cannons, its interior has a central courtyard with buildings around three sides.42This fort's construction heralded the end of Kilwa kisiwani as an independent city-state. In the early 19th century, the center of trade in the Kilwa and Mafia archipelagos shifted to the mainland town of Kilwa Kivinje.

Kilwa’s last ruler, sultan Hassan, was exiled by the Omani rulers of Zanzibar in 1842, and the once sprawling urban settlement was reduced to a small village.43

The city of TIMBUKTU was once one of the intellectual capitals of medieval Africa. Read about its complete history on Patreon;

from its oldest iron age settlement in 500BC until its occupation by the French in 1893. Included are its landmarks, its scholarly families, its economic history and its intellectual production.

if you liked this Article and would like to contribute to my African History website project, please donate to my paypal

The Swahili: Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society, 800-1500 by Derek Nurse and Thomas Spear

A Material Culture by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 24-34, 23)

Ceramics and the Early Swahili: Deconstructing the Early Tana Tradition by Jeffrey Fleisher & Stephanie Wynne-Jones

A Material Culture by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 60-61)

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 21)

A Material Culture by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 71

A Material Culture by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 61-65)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 42

Horn and cresecnt by R. Pouwels pg 34-37, Swahili Origins by James de Vere Allen pg 200-215

A Material Culture by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 55)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 245-252

Horn and cresecnt by R. Pouwels pg 25)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 242, The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa by Timothy Insoll pg 186)

the pre-Kilwa origins of the Mahdali is given as Mafia in the kilwa chronicle and possibly tumbatu, but Sutton made a convincing hypothesis based on archeological finds of gold coins at tumbatu. see ‘A Thousand Years of East Africa by JEG Sutton’

The African Lords of the Intercontinental Gold Trade Before the Black Death by JEG Sutton pg 228-234)

A Thousand Years of East Africa by JEG Sutton pg 81-82)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 56)

A Material Culture by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 73-74)

Kilwa Dynastic Historiography: A Critical Study by Elias Saad pg 184-193

A Material Culture by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 66

Kilwa a history by J.E.G sutton pg 135-139)

A Material Culture by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 65-68)

This and similar plans are taken from J.E.G sutton

Swahili pre-modern warfare and violence in the Indian Ocean by Stephane Pradines pg 15-16 )

Kilwa a history by J.E.G sutton pg 150-156)

Inter-Tidal Causeways and Platforms of the 13th- to 16th-Century City-State of Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania by Edward Pollard pg 106-113

credit; Edward Pollard

The complexity of public space at the Swahili town of Songo Mnara, Tanzania by Jeffrey Fleisher, pg 4-6

Kilwa a history by J.E.G sutton pg 145

A Material Culture by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 49-50)

Coins in Context: Local Economy, Value and Practice on the East African Swahili Coast by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 23-24)

Kilwa-type coins from Songo Mnara, Tanzania by J. Fisher pg 112)

Coins in Context: Local Economy, Value and Practice on the East African Swahili Coast by Stephanie Wynne-Jones 31-34)

The Arts and Crafts of Literacy by Andrea Brigaglia, Mauro Nobili pg 181-203)

International Journal of African Historical Studies" Vol. "52", No. 2, pg 263-268

A Material Culture by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 58

Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa by Edward A. Alpers pg 42-46)

The Role of the Yao in the Development of Trade in East-Central Africa pg 60-72

Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa by Edward A. Alpers pg 50, 59-62)

A Revised Chronology of the Sultans of Kilwa in the 18th and 19th Centuries by Edward A. Alpers pg 156-159

Kilwa a history by J.E.G sutton pg 142

Kilwa a history by J.E.G sutton pg 149

A Revised Chronology of the Sultans of Kilwa in the 18th and 19th Centuries by Edward A. Alpers pg 160

Hello, I haven’t finished reading this but it is so very interesting I was born in Lamu island and I know I am connected to Kilwa somehow I’m doing a lot of research this time I was looking about something to do with my language Swahili,, part of my DNA has led me to Kilwa and so many other parts…Thank you

Interesting

Is there any counter-theory about the supposed Persian-Ethiopian origins of the first Kilwa Sultan?