Navigable waterways in African history

Pre-colonial African coastal societies had extensive experience with seaborne navigation, which opened up connections between the continent and the rest of the Old World.

Sailors from the Aksumite empire dominated maritime activity in the Red Sea region during late antiquity and were involved in the transshipment of trade goods from India and Sri Lanka to Roman ports in Egypt and Jordan.

Coastal communities in the medieval cities and offshore islands of East Africa, extending from Somalia to Mozambique built ships that plied the great water routes of the Indian Ocean from the Arabian coast to Malaysia.

Dhow under construction, ca. 1945, Tadjourah, Djibouti. Quai Branly. image of a shipyard with dhows under construction, showing scaffolding and thatching. ca. 1884, Moroni, Grande Comore. Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle.

Swahili Ship graffiti from Tanzania dated 13th-16th century: a, c: from Great Mosque, Kilwa Kisiwani; b, from Husuni Kubwa, Kilwa Kisiwani; d, from Palace, Songo Mnara; e, from House 17, Songo Mnara. (after Garlake and Garlake 1964).1

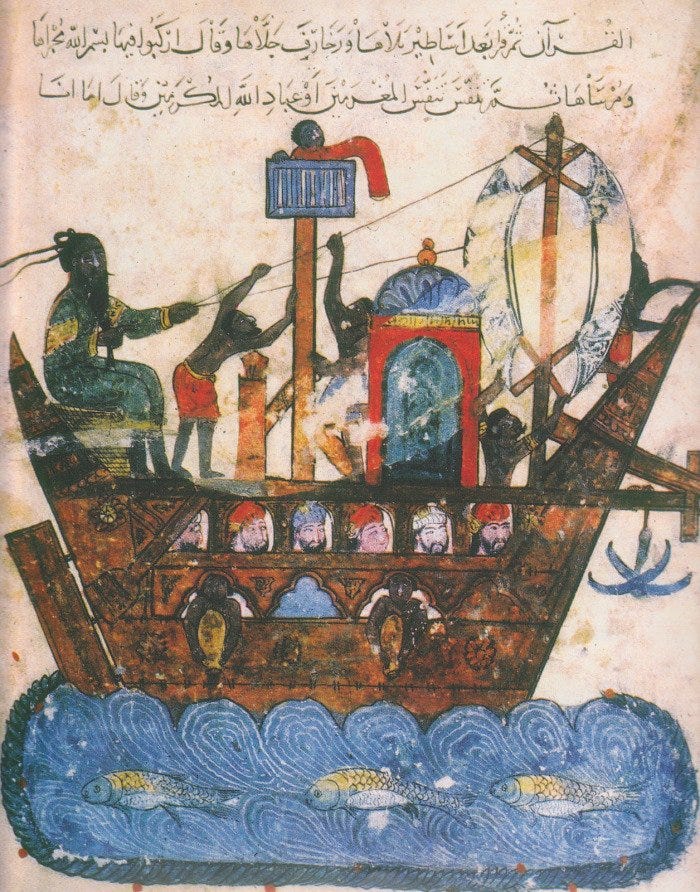

Illustration of a ship engaged in the East African trade in the Persian Gulf. 1237, Maqamat al-Hariri.2

While the relatively well-documented external navigation of these African societies along the Eastern coast of the continent has attracted significant scholarly interest, there is less research on internal waterborne traffic within the continent, whose lakes and rivers are erroneously thought to have been impossible to navigate.

Despite the often-repeated claim that Africa lacked navigable waterbodies, there’s plenty of historical evidence for trade and travel across the continent’s many rivers, lakes, and coastal waterways which contradicts this popular misconception.

The historian John Thornton argues that the Niger-Senegal-Gambia river complex united a considerable portion of West Africa from Senegal through the Hausalands and down to Benin, into a hydrographic system that was ultimately connected to the Atlantic. He writes:

“Geographical ideas held by Africans and outsiders alike in the sixteenth century conflated all these rivers —the Senegal, Gambia, Niger, and Benue— into a single ‘Nile of the Blacks’ ultimately connected to the Nile of Egypt. Although it is mistaken geography, it is a real reflection of the transport possibilities of river routes.”3

Navigable sections of the Niger River. Map by author from a study on the History of Navigation of the Niger River. note that this study doesn’t include the navigable sections of the Senegal, Gambia, and Benue rivers.

The historical evidence of navigation along the Niger River from Guinea to Nigeria's delta region supports Thornton's argument. Local chronicles from the 17th century combined with European travel accounts from the 18th and 19th centuries document the extensive use of large river barges on the Niger River for trade and travel between the great cities of the region.

These barges and other large rivercraft could carry more cargo than porters and most caravans, significantly reducing the cost of transportation and increasing the volume of regional trade.

The river barges of the Songhai empire that were mentioned in the 17th-century Timbuktu chronicles, could carry up to 30 tonnes of grain from Djenne to Gao. The same barges were encountered by the French traveler Rene Caillie in the 1820s, who mentions that the barges had a capacity of 60-80 tons, measured about 100ft long and 14ft wide, had a crew of 18 including the captain, and could accommodate more than 50 other passengers alongside their animals and cargo.4

In the lower section of the Niger River in Nigeria where one visitor in 1832 claimed that “there appeared to be twice as much traffic going forward here as in the upper parts of the Rhine,” large vessels measuring 70ft long and 8 ft wide, with benches for 20 rowers and a capacity to carry 80 passengers and their cargo, were being constructed as early as the 17th century.5

Barge on Timbuktu's river port of Kabara, ca. 1930-1939, Quai Branly

Large canoe with a square sail and partially sheltered deck, on the Ogun River near Lagos, Nigeria, ca. 1883. Basel mission archives.

Riverine transport was greatly preferred by the merchants in this region. Whereas a porter would carry 60-70 lbs and a donkey would carry 100-120 lbs, a small canoe would carry 2 tons and a large one 20-30 tons of trade goods. What two men could accomplish propelling a small canoe would be carried by 64 porters, and a big canoe could replace more than 600 porters.6

Thornton also argues that the region of West-Central Africa was oriented by its rivers, especially the lower Congo and the Kwanza rivers which bore substantial commerce. The Kwanza in particular was a major artery of commerce for neighboring African kingdoms such as Angola/Ndongo and played a significant role in the military history of the region. So too did the Congo River and its tributaries, where riverine trade flourished among societies along the lower sections of the river.7

This riverine commerce was ultimately connected with coastal commerce as African vessels plied the coastal waters between central Africa and West Africa.

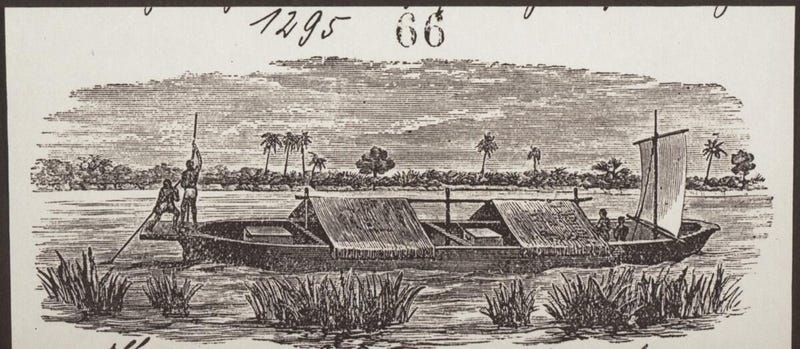

Illustration of a Dhow on the Congo River, ca. 1888, D.R.C

Local sailboats near Dakar, Senegal, ca. 1906-1910, Edmond Fortier collection

My previous essay on Seafaring, trade, and travel in the African Atlantic, shows how local maritime activity by African sailors along the continent’s Atlantic shoreline created a highway that nurtured trade, travel, and migration from West Africa to west-Central Africa. Some of the maritime societies of this region such as the Mpongwe of Gabon constructed large sailboats which were so well built that they “would land them, under favorable circumstances, in South America” according to a 19th-century visitor.

Similar dynamics of waterborne travel were attested in the Great Lakes region of East Africa, where the lakes Victoria, Tanganyika, and Malawi have been navigable for much of their known history.

In this region, a series of some of Earth's largest freshwater lakes constituted a crucial waterway for trade and travel between the various kingdoms and societies of the East African mainland. Using a variety of watercraft ranging from sea-worthy Dhows to large riverine canoes that could carry up to 80 passengers; travelers, merchants, and navies from surrounding lacustrine societies crisscrossed these vast waterbodies and established lake ports whose significance to regional trade would be retained well into the modern era.

The history of Navigation on the African Great Lakes is the subject of my latest Patreon article,

please subscribe to read more about it here:

Dhow near Cape Maclear, Lake Malawi. Alamy Images.

When Did the Swahili Become Maritime? by Jeffrey Fleisher et al.

Trade in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond edited by D. J. Mattingly pg 147

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800 by John Thornton pg 19

Timbuktu and Songhay by John Hunwick pg xxxi, li, 304 n.38, African Dominion by Micahel Gomez pg 341-342, Travels through central Africa by René Caillié Vol. 2, pg 5, 9-12

The Canoe in West African History by Robert Smith pg 518, 528

Human porterage in Nigeria by Deji Ogunremi pg 39)

Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800 by John Thornton pg 19, River of Wealth, River of Sorrow: the Central Zaire Basin in the era of the slave and ivory trade, 1500-1891 by R.W.Harms,

Really appreciate and like all this amazing research you do on African histories