The Hausa city of Kano is one of west Africa's oldest and best documented capitals, with a long and complex political history dating back nearly a thousand years. The city-state was ruled by a series of powerful dynasties which transformed it into a major cosmopolitan hub, attracting merchants, scholars and settlers from across west Africa.

Wedged between the vast empires of Mali, Songhai and Bornu, the history of Kano was invariably influenced by the interactions between exogenous and endogenous political processes. Kano managed to maintain its autonomy for most of its history until it fell under the empire of Sokoto around 1807 when the city-state was turned into an emirate with an appointed ruler. It would thereafter remain a province of Sokoto with varying degrees of autonomy until the British colonization of the region in 1903.

This article outlines the political history of Kano, highlighting the main events that occurred under each successive king.

Map of west africa showing the location of Kano state in the 18th century1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The early history of Kano, like the Hausa city-states begun around the turn of the 2nd millennium following the expansion of nucleated communities of agro-pastoral Chadic speakers into the region west of lake chad. The earliest of such complex societies within what would later become Kano was established around the Dalla Hill, and its from this and similar communities that the walled urban states of Hausa speakers would emerge.2

This early history of Kano is mostly based on the faint memories preserved in later chronicles, as well as archeological surveys of the walls of Kano, both of which place the city’s emergence around the 11th/12th century3.A few of the earliest Sarki (King) of Kano that are recorded in the Kano chronicle (Bagauda r. 999-1063, and Warisi r. 1063-1095) seem to have been legendary figures, as more detailed descriptions of events during their reign don’t appear until the reign of Warsi’s sucessor Gijimasu (r. 1095-1134) who is credited with several conquests. 4

During Gijimasu's reign, the emerging Hausa polities at Rano, Gaya and Dutse were also expanding in the regions south of Kano, and their rulers constructed defensive walls like Kano’s from which they subsumed nearby communities. Besides these competitors that Gijimasu's young state faced were also many polities like Santolo, that are identified as non-Muslim. But its unclear if Islam had already been adopted by Gijimasu’s kano at this early stage since the first Muslim king —Usumanu— appears in the 14th century.5

the inselberg of Dalla in Kano

city walls of Kano

Gijimasu was suceeded by Yusa (1136-1194) who expanded Kano westward to the town of Farin ruwa in what would become the border with Katsina. Yusa's sucessor Naguji (1194-1247) expanded Kano to the south-east beyond Dutse and Gaya, down to the town of Santolo. Naguji's sucessor Guguwa (1247-1290) spent most of his reign consolidating the state, and contending with the traditional elites but was ultimately deposed.6

Guguwa was suceeded by Shekarau (1290-1307) who was also pre-occupied with reducing the power of the traditional elite with the dynastic title of Samagi, but was forced to tolerate them in exchange for tribute. It was under his successor Tsamiya (1307-1343) that the power of the Samagi and other traditional elites was reduced, and their administration placed under three appointees (including the Sarkin Cibiri) whose authority was derived from Tsamiya.7

Usumanu Zamnagawa suceeded Tsamiya after a executing the latter in a violent succession. Usumanu's reign (1343-1349) coincided with the period of the Mali empire's expansion eastwards beyond the bend of the Niger river. He subsumed allied traditional elites like the Rumawa under his adminsitration but others like the Maguzawa retreated to the frontier.8

A recurring theme in the Hausa chronicles of the 19th century is the dichotomous relationship between the gradually Islamizing population and the non-muslim groups, both within Kano's domains and outside it.9 Many Hausa traditional religions and elite groups are described at various points in different accounts, and like their muslim-Hausa peers, none of the non-muslim Hausa communities represented a unified whole, but appear to have been autonomous communities whose political interests of expansion and consolidation mirrored that of the Muslim Hausa. The classifications of different groups as ‘Muslim’ or ‘non-muslim’ is therefore unlikely to have been fixed, and would have been increasingly contested as Islam became established as the official religion of Kano.10

Usumanu was succeeded by Yaji who welcomed the Wangarawa (wangara) from Mali who were appointed in the administration, and instituted the offices of imam, alkali (judge) and ladan. Yaji reduced the stronghold of the last traditional elites at Santolo, and campaigned southwards to the territories of the Kworarafa (jukun) which was likely where he ultimately died. It was under Yaji that the Hausa city of Rano came under Kano's suzeranity.11

Approximate extent of Kano during Yaji’s reign.

Yaji was suceeded by Bugaya (1385-1390) who managed to integrate Maguzawa into his administration under an appointed chief. Bugaya added several offices to accommodate the expanding state's administration and Islam's institutionalization. He was suceeded by Kanajeji (1390-1410) who, through his wangarawa allies, created a force of heavy cavalry and campaigned to the territories of the Jukun, Mbutawa and Zazzau (Zaria) with rather mixed results.12

After consulting with his Sarkin Cibiri who advised him to reinstate the cult inorder to acquire battle success. Kanejiji thus reduced the influence of the wangarawa and Islam at his court in exchange for military assistance from the levies controlled by the Sarkin Cibiri. Kanejiji's campaign against Zaria was successful but the borders of Kano remained unchanged. Kanejiji was suceeded by Umaru (1410-1421) who had studied under the wangara named Dan Gurdamus Ibrahimu and thus reinstated the influence of the wangara and Islam at his court upon his ascension.13

Umaru reduced the power of the non-Muslim elite (presumably the Sarkin cibiri). Umaru's assumption of power was resented by his friend Abubakar, a scholar from Bornu who advised him to abdicate twice before Umaru finally relented in 1421, and both retired outside the city walls. Umaru was suceeded by Dawuda (r. 1421-1438) who invited the deposed Bornu prince Othman Kalnama into kano, and left the state under him while he was campaigning against Zaria.14

Zaria under princess Amina, had expanded across the southern frontier of Kano, taking over much of the tribute it had received from the Jukun territories. Dawuda was however, unable to restore Kano's suzeranity over the Jukun. He was suceeded by Abdullahi Burja (r. 1438-1452) under whose reign Kano came under the suzeranity of the Bornu empire. Burja subsumed the hausa cities of Dutse and Miga which became tributary to Kano, and established the market of Karabka with the assistance of Othman Kalnama.15 It was during his reign that the Wangara scholary family of Abd al-Rahmán Jakhite arrived in Kano from Mali and would retain a prominent position in the ulama of Kano.16

Burja was briefly suceeded by two obscure figures; Dakauta and Atuma before the accession of Yakubu in 1452. Yakubu had been installed with the support of Gaya, which had submitted peacefully to Kano, and it was during his reign that Kano acquired its fully cosmopolitan character. As the chronicle mentions; "In Yakubu's time, the Fulani came to Hausa land from Mali bringing with them books on divinity and etymology. Formerly our doctors had, in addition to the Koran, only books of the Law and traditions. The Fulani passed by and went to bornu, leaving few men in Hausaland. At this time too the Asbenawa (Tuareg) came to Gobir and salt became common in Hausaland. In the following year merchnats from Gwanja (Gonja) began coming to Katsina; Beriberi came in large numbers and a colony of Arabs arrived." Evidently, most of these connections had already been established especially with the regions of Mali and Gonja, and they were only intensified during Yakubu's reign.17

Yakubu was suceeded by Muhammad Rumfa (r. 1463-1499) who fundamentally reorganized Kano's political institutions. Rumfa is credited with several innovations in Kano including the creation of a state council, the construction of two palaces, a market, and the expansion of the city walls. Other innovations including the creation of new administrative offices, the adoption of Bornu-style royal regalia and the creation of a new military units and the institution of the religious festivals.

During Rumfa's reign, the magrebian scholar al-Maghili was invited to Kano around 1493 as part of his sojourn in west Africa after having been expelled from his home in southern Algeria. Al-Maghili was personally hosted by Rumfa who provided the former with houses, supplies and servants.18 Al-Maghili wrote an important letter addressed to Muhammad ibn Yakubu (ie: Rumfa) in 1492 during his stay in Kano, and would later compose a work titled "the obligation of Princes" at Rumfa's request. Rumfa spent the rest of his reign fighting an inconclusive war with Katsina.19

Rumfa was suceeded by Abdullahi (1499-1509), who was the son of Hauwa, a consort of Rumfa who later became a prominent political figure and was given the office of Queen mother. While Abdullahi was campaigning against Katsina and Zaria, Hauwa restrained the power of Othman Kalnama's sucessor Dagaci, who attempted to seize the throne. Abdullahi renewed his submission to the Bornu ruler for attacking the latter's vassals, before expelling Dagaci for his insubordination. Both Katsina and Zaria would later band together in an alliance against Kano shortly before Abdullahi's death.20

Muhammadu Kisoke (r. 1509-1565) suceeded Abdullahi and inherited the latter's conflict with Katsina and Zaria which now acquired much larger regional significance. The expansionist empire of Songhai under Askiya Muhammad, which had advanced beyond the region of Borgu and Bussa, begun making incursions into the Hausalands. Between 1512-1514, the Askiya allied with Katsina and Zaria to overrun Kano before conquering all three states, but a rebellion by his general named Kanta around 1516 resulted in all three falling under Kanta's empire based at kebbi. Kisoke likely served as the Kanta's deputy until the latter's passing around 1550.21

Kisoke later freed himself from Kebbi's suzeranity and refused to submit to Bornu, managing to repel an attack on Kano by the latter in the 1550s. Kano was then fully independent after over a century of imperial domination and Kisoke credited many of his councilors for this accomplishment.22 He also invited more scholars to Kano including the Bornu scholars Korsiki, Kabi and Magumi (the last of whom became the alkali) as well as the Timbuktu scholar Umar Aqit, and the Maghrebian scholars Makhluf al-Balbali, Atunashe and Abdusallam. All of these are variously credited with bringing with them books on law eg the al-Mudawwana of Shanun.23

It was during Kisoke’s reign that Kano first appeared in external accounts. Its earliest mention was by Leo Africanus whose 1550 description and map of Africa included the other Hausa city-states neighboring Kano was most likely obtained from informants at Gao or Timbuktu.24 An identical description was provided by the geographer Lorenzo d'Anania in 1573 based off information he received while he was on the west African coast. Hewrote of Kano, with its large stone walls, as one of the three cities of Africa (together with Fez and Cairo) where one could purchase any item.25

Gidan Rumfa, the 15th century palace of Kano

detail from Leo Africanus’ 16th century map of Africa showing atleast 4 Hausa cities including Cano (Kano)

Kisoke was briefly suceeded by Yafuku and Dauda Abasama. Both of them were however deposed by the council in favor of Abubakar Kado (r. 1565-1573) whose reign reflected the internal divisions between several powerful factions in Kano. The state was invaded by Katsina, and the ineffective but devout Kado spent most of his time studying. Kado was deposed and Muhammad Shashere (1573-1582) was appointed in his place. But the internal divisions persisted, Shashere led a failed battle against Katsina, was abandoned and nearly assassinated, and was later deposed.26

Shashere was suceeded by Muhammadu Zaki (1582-1618). Zaki was faced with the first of the Jukun invasions in 1600 which, along with minor incursions from Katsina, devastated Kano and intensified the period of famine that would last 11 years. Zaki successfully attacked Katsina but died in the frontier town of Karaye. He was suceeded by Muhamman Nazaki (1618-1623) who defeated the Katsina army while one of his officers, the Wambai Giwa repaired and expanded Kano's walls. 27

Nazaki was suceeded by Muhammad Alwali Katumbi (1623-1648) The latter continued Kano's war with Katsina all while he elevated and reduced the power of individual offices to preserve central control. He demoted the Wambai Giwa, elevating the Kalina Atuman and the Dawaki Koshi, before both were tactically eliminated. He introduced taxes on the itinerant herdsmen, and created more offices of adminsitration. Kutumbi died in 1648 after a failed attack on Katsina, and was briefly suceeded by Alhaji and Shekarau (1648-1651), the latter of whom made peace with Katsina.28

Shekarau was suceeded by Kukuna (1651-1660) who managed to crush a brief coup early in his reign using the support of his councilors. However, Kano was shortly after attacked by the Jukun and Kukuna was forced to abandon the capital. Weakened by defeat, Kukuna employed the services of the Maguzawa (one of the non-muslim groups) and the Limam Yandoya (a muslim priest), but, failing to secure his power, he was deposed29. The chronicle of the wangara of Kano was written at the start of his reign.30

Kukuna was suceeded by Bawa (1660-1670) a devout figure who spent his time studying while the councilors ran the state. Bawa was suceeded by Dadi (1670-1703) who had to contend with the power of the council. His attempt to expand the city was hindered by local clerics supported by the council, so when the Jukun marched against Kano around 1672 but Dadi was prevented from mustering his forces to meet them. Under the galadima Kofakani's influence, Dadi briefly restored the Chibiri and Bundu cult sites, before removing them. The ruler of the town of Gaya rebelled but was executed by Dadi who appointed a loyalist in his place.31

Dadi was suceeded by Muhammadu Sharefa (1703-1731) who spent most of his reign crushing rebellions and fending off a major invasion from Zamfara's ruler Yakuba Dan Baba. After surviving the attack by Zamfara, Sharefa introduced new taxes/levies across the state in response to the introduction of cowries (from the Atlantic) and partly to pay for the fortification works undertaken during his reign. His sucessor, Kumbari (1731-1743) also spent his reign crushing rebellions, notably at Dutse, and fending off a major invasion from Gobir.32

Kumbari greatly expanded the taxation policy of his predecessor, especially after the re-imposition of Bornu's suzeranity over kano in 1734. The tax burden imposed on all sections of society forced the merchants to flee to Katsina and the poorer classes to retreat to the countryside. Kumbari was suceeded by Alhaji Kabe (1743-1753) who suceeded in consolidating Kano's internal politics but had to contend with an attack by Gobir. Kabe was succeeded by Yaji ii (1753-1768) who was largely a figured of the councilors that had elected him and wielded little authority.33

Yaji used the little influence he had to appoint a trader named Dan Mama as the ciroma (crown prince), giving the latter substantial fief holdings that allowed him to raise cavalry units and accumulate wealth to influence the council. Yaji thus secured the continuity of his line, and was succeeded by his son Babba Zaki (r. 1768-1776) who greatly centralized political and military power at the expense of the council and other elites whose power was reduced. He created a guard of musketeers and expanded the state through his conquests, notably of Burumburum.34

approximate extent of Kano during the 18th century

Zaki was suceeded by Dauda Abasama (r. 1776-1781) who restored the power of the council and the Galadima, and his reign was relatively peaceful. Dauda was suceeded by Alwali (r. 1781-1807) who would be the last Hausa king of Kano. Alwali was faced with several endogenous and exogenous challenges including the persistent cowrie inflation, a populace disaffected with the high taxation and a growing politico-religious movement led by Fulbe clerics led by the Sokoto founder Uthman Fodio, who were opposed to Alwali’s government.

After a lengthy period of war from 1804-1807 that culminated with the battle of Dan Yaya, Alwali's forces were defeated by the Fulbe forces and the king was forced to flee to Zaria. Alwali later moved to Burumburum and instructed his only remaining loyal vassal at Gaya to attack the Fulbe forces led by a Fulbe general named Muhammad Bakatsine, but the Gaya forces were defeated. Bakatsine then turned to Burumburum and defeated the forces of Aklwali, with only the latter's son, Umaru, escaping to Damagaram to find other deposed Hausa kings who would later establish the city-state of Maradi.35

The office of Sarki (sultan/King) was abolished as the city-state was now one of several provinces under the Sokoto caliphate of Uthman Fodio. The Sarki was now replaced by an 'Emir' appointed by the Sokoto leaders, and several months after the battle of Dan Yaya, a fulbe imam named Suleimanu (r. 1808-1819) was chosen as emir of Kano. Suleimanu was of humble background and hadn't participated in the wars of conquest, so he was generally despised by the Fulbe aristocracy of Kano. This was compounded by the aristocracy's revival of the pre-existing Hausa institutions that undermined central authority of the Sarki while raising that of the councilors and provincial lords. Suleimanu died in 1819, reportedly after he had chosen the Galadima, Ibrahim Dabo as his heir and communicated this to Muhammad Bello, the sucessor of Uthman Fodio.36

Ibrahim Dabo (r. 1819-1846) begun his reign from an unfavorable position, facing political opposition from most Fulbe elites in Kano and across Sokoto, and with an empty treasury. He thus revived all pre-existing Hausa institutions and offices, thus restoring the tribute system that the Sarki was entitled to by doubling taxes (from 500 cowries of Alwali's reign to 1,000) and expanding the classes exempt to the tax. Rebellions among the opposing Fulbe were crushed after nearly a decade of extensive campaigning, he restored central authority to the office of the Sarki, and gradually filled the princely offices of administration with his kinsmen.37

It was during Dabo's reign that the explorer Hugh Clapperton visited Kano in 1824. Clapperton described Kano as a large, walled city of about 40,000 residents, and that 3/4 of the city was "laid out in fields and gardens". Adding that the gidan rumfa as a walled palatial compound with a mosque and several towers three or four stories high. Dabo's reign overlapped with the sucession of the Sokoto caliphs Abubakar Atiku (r. 1837-1842) and Aliyu Baba (r. 1842-1859), the latter of whom appointed Dabo's son Usuman to succeed his father as emir of kano.38

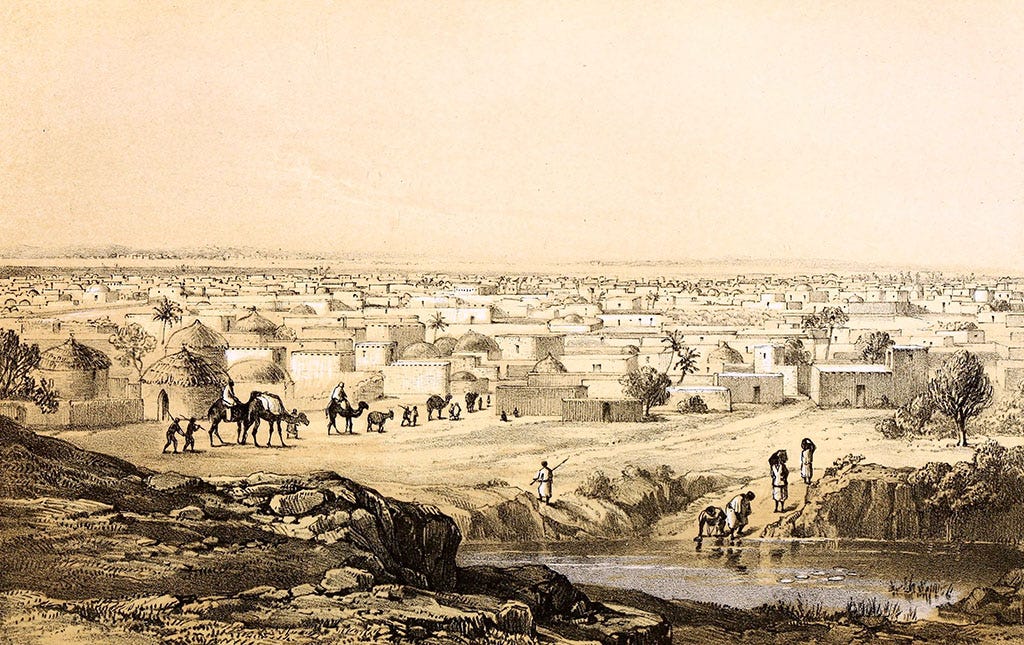

Usuman (r. 1846-1855) was rather ineffective emir, and the government was largely in the hands of the Galadima Abdullahi, who was Usuman's brother. A drought-induced famine in 1847, and its corresponding increase of taxes (from 1,000 to 2500 cowries), instigated the first major hausa uprising in Kano which allied with the non-Muslim Hausa such as the Ningi, Warajawa and Mbutawa to attack several towns. It was during Usuman's reign that the explorer Heinrich Barth visited Kano, corroborating most of clapperton's account but providing more detail about the city's commerce and the state revenues.39

painting of Kano from Mount Dala by H. Barth, 1857

Kano cityscape in the early 20th century

After Usuman's death, the Galadima Abdullahi suceeded him in a palace coup that involved Abdullahi voiding the official letter of Aliyu that was being read before Kano's aristorcracy by the Sokoto wazir Abdulkadiri. Aliyu immediately summoned Abdullahi to reprimand him but later accented to the latter's sucession after he had proved his loyalty. Most of Abdullahi's reign was spent repelling the Ningi attacks in southern Kano in 1855, 1856, 1860 and 1864 which devastated several towns. He fortified many of the vulnerable towns in the 1860s around the time when the explorer W.B Baikie was visiting, but failed to decisively defeat the incursions, losing a major battle in 1868. 40

Abdullahi placated his aristocracy through marriage alliances, centralized his power by creating new hereditary offices and increased his support among the subject population by slightly lowering taxes (from 2500 cowries to 2000) passing on the remainder to the itinerant herders. Despite his conflict with the emir of Zaria over taxation of itinerant herders, Abdullahi forestalled a succession dispute in Zaria by playing an influential role in the politics at the imperial capital of Sokoto.41 It was during his reign that the chronicler Zangi Ibn Salih completed a work on the history of Kano titled Taqyid akhbar jamat, in 1868.42

Abdullahi died in 1882 and was succeeded by Muhammad Bello, following the latter's appointment by Sokoto Caliph Umaru. Muhammad Bello's reign from 1882 to 1892 was marked by internal rivalries among the numerous dynastic lineages and changes in administrative offices43. Bello chose the Galadima Tukur as his successor by transferring significant authority to the latter. The political ramifications of this decision would influence the composition of the Kano chronicle by Malam Barka.44 Tukur was later appointed as emir of Kano in 1893 by the caliph Adur against the advice of his courtiers and the Kano elite who preferred Yusuf.45

Copy of Malam Barka’s Kano chronicle46, originally written in the late 1880s

A brief but intense civil war ensued between Tukur's forces and the rebellion led by Yusuf between 1893-1894, with Yusuf capturing parts of southern Kano. Yusuf died during his rebellion and was suceeded by his appointed heir, Aliyu Babba who eventually defeated Tukur and was recognized as emir by the caliph Adur. But Yusuf refused to pay allegiance to the caliph that had rejected him, chosing to rule Kano virtually independently. Aliyu reorganized the central administration of Kano and forestalled internal opposition. These changes would prove to be critical for Kano as new external threats appeared on the horizon.47

The first threat came from Zinder, the capital of Damgaram whose ruler Ahmadu Majerini directed two major attacks against Kano in 1894 and 1897 that inflicted significant losses on Aliyu's forces, before Majerini was himself defeated by the French in 1899. To the far south of Kano, the British had captured the emirate of Nupe in 1897 and were advancing northwards through Zaria, whose emir sent frantic letters warning Aliyu of the approaching threat. Aliyu thus pragmatically chose to resubmit to Sokoto's suzerainty right after the death of caliph Abdu and the succession of Attahiru.48

Aliyu set out with the bulk of his forces to the capital Sokoto to meet Attahiru, the forces of Lord Lugard which had intended to march on Sokoto instead moved against Kano in January 1903. The small detachments Aliyu had left at Kano fought bravely but in vain, and the British forces stormed the city. 49 Aliyu would later attempt to retake the city, and for most of February 1903, his forces were initially successful in skirmishes with the British but later fell at Kwatarkwashi, formally ending Kano's autonomy.

on AFRICANS DISCOVERING AFRICA: Far from existing in autarkic isolation, African societies were in close contact thanks to the activities of African travelers. These African explorers of Africa were agents of intra-continental discovery centuries before post-colonial Pan-Africanists

Most of this article is based on the Kano chronicle of Malam Barka as translated by H. R. Palmer and M.G.Smith

Map by Paul E. Lovejoy

This is a summary of my previous article on early Hausa history

African Civilizations: An Archaeological Perspective By Graham Connah pg 125

The Kano chronicle by H. R. Palmer, pg 65

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 112-113

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 114)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 115)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 116)

A Geography of Jihad by Stephanie Zehnle pg 84-87

Being and Becoming Hausa by Anne Haour and Benedetta Rossi pg 15-17

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 117-118, 126)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith 120)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 121-122

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 123-124

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 124-127

Beyond Jihad by Lamin Sanneh pg 103-106, but Hunwick mentions they arrived just before al-Maghili did during Rumfa’s reign around 1493, see: n.6, pg 30, John O. Hunwick, "Sharia in Songhay”

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 128

Shari'a in Songhay: the replies of al-Maghili to the questions of Askia al-Hajj Muhammad by J. Hunwick pg 39-40

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 2. by J. Hunwick pg 20-22

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 136-137

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 138-140

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 142-143

Social History of Timbuktu by Elias Saad by 58, Arabic Literature of Africa Vol. 2 pg 25, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 52-53

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 287

Being and Becoming Hausa by Anne Haour and Benedetta Rossi pg 10

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 146-148

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 149-152

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 153-158)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 158-160)

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 2. by J. Hunwick pg 582

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 162-164)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 165-167)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith 168-169)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 170-172,

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 194-199)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 210-222)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 223-243)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 244-251)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 253-260)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 271-278)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 279-299)

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 2. by J. Hunwick pg 342

Alhaji ahmed el-fellati and the Kanon civil war by P. Lovejoy pg 52-55

Landscapes, Sources and Intellectual Projects of the West African Past by Toby Green et al, pg 404-407

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 304-327, 340)

The Kano chronicle by H. Palmer, in “Journal of The Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. XXXVIII,” 1908, Plate IX

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 345-374)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 378-384)

Government in Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith pg 384-386)

Excellent read

I have to now pause midway through your article to find a better description of the Cowrie trade, as well as a chronological description of Portuguese and British monetary and fiscal policies of the time.

So as to overlay the counter-inflation policies you describe of Kano governments, especially the Hausa and match it chronologically with the monetary policies of first the Portuguese emperium (which maintained the monetary policies of the Holy Catholic Empire) and then the British Shilling area policies intentionally designed for colonialism by Newton.

Hope to gain insight on how much additional effect on targetted economies those policies of Newtons may have had as compared to the Portuguese policies.

Your chronology here and your references allow me to do that.

Brilliantly written, inspired insights.

Thanks again