The empire of Segu (1712-1861): ethnic ambiguity in a pre-colonial African state

In the wake of Songhai's collapse, the market town of Segu in Mali was established as the capital of an eponymous empire at the turn of the 18th century.

Situated between the former frontiers of medieval Mali in the west and Songhai in the east, Segu became the most influential among the Bambara states that dominated the political landscape of the region.

The Bambara kings at Segu reigned along the Niger River between Bamako (the present capital of Mali) and the old city of Timbuktu, controlling trade between Djenne and a string of towns populated by Marka traders and Somono boatmen.

The ethnogenesis of these three population groups in relation to the emergence and expansion of the Segu empire is one of the best studied among the pre-colonial societies of West Africa.

The historical fluidity of social boundaries in Segu reveals the ambiguity of ethnic identities in Africa, which were (are) continuously reshaped through political and social practices.

This article explores the social history of the empire of Segu between the 18th and 19th centuries.

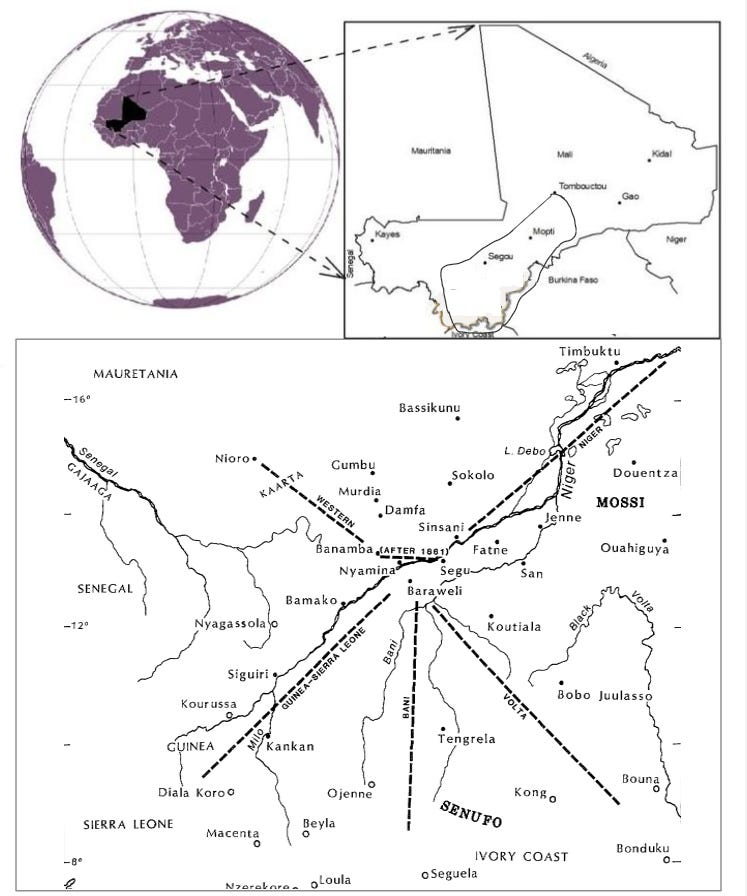

Map showing the Segu domains in the 18th century

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early history of Segu

After the collapse of the western provinces of the Songhai empire at the end of the 16th century, smaller polities that had been submerged in the imperial system asserted their political independence.

Among these were the Bambara (also known as the Banmana), who are closely related to the Malinke of medieval Mali, but constitute an ambiguous ethnic/social group whose identity oscillated with the shifting political history of the region. Historians suggest that the Bambara's ethnic self-identification did not begin until the height of the Segu state in the 19th century, even though the ethnonym existed in the medieval period and appears relatively early in the Atlantic world.1

The Bambara region was first mentioned in local chronicles among the provinces of medieval Mali in the 14th century, and later as a generic term for the ‘pagan’ adversaries of the city of Djenne in the 16th century, who were subjected to raids by the Askias of Songhai. Two Bambara polities mentioned in this period are Kala and Bendugu, which had many rulers based in different capitals. Some hosted Songhai elites, adopted Islam, and even produced scholars such as Bukar Tarawure, a qadi of Djenne in the 17th century.2

The exact origins of the Bambara kingdom at Segou (Segu) are obscured by the diversity of oral and written accounts about the first dynasty known as the Coulibali/Kulubaly in the 17th century. Traditions that were first transcribed during the mid-19th century mention the arrival of this royal lineage (or its founder) in the vicinity of Segu around 1650 in an area inhabited by the Soninke (Marka) and other Mande-speaking groups.3

Accounts of Segu's early history are centred around the career of the state's putative founder, Biton Kulubaly (1712-1755), one of the scions of the aforementioned dynasty. The historical traditions emphasize Biton's military prowess, his election as the leader (ton-tigi) of associations of age sets known as the ton, and his gathering of followers at Segou-koro, which became the kingdom's first capital.4

The heartland of Biton's Segu kingdom was in the middle valley of the Niger River. This was a multi-ethnic region inhabited by the Somono, Bambara, and Marka, as well as other groups such as the Bozo, Dogon, Fulbe, and the Songhay, who specialized in different occupations.

Local chiefs, whose position was menaced by the growing power of Biton and his forces, called in the aid of the southern kingdom of Kong in what is today northern Côte d’Ivoire. The founder of Kong, who initially claimed Biton’s Kulubaly lineage before adopting the Mande patronymic of “Watara,” was at the time consolidating his kingdom. His troops arrived at the gates of Djenne in 1739, but Segu was only saved by the intervention of the Fulbe of Fuladugu (from Senegal), who routed Kong's army.5

During Biton’s reign, some Bambara groups that had previously served as his mercenaries moved north of the river to found the kingdom of Kaarta. (It should thus be noted that there were many Bambara kingdoms besides Segu) The city of Djenne recognised the suzerainty of Segu, albeit nominally, while revolts around the town of Sinsani (Sansanding) continued until the end of his reign.6

Evidence of settlement abandonment in the Middle Niger region during the 18th century and the emergence of a new ceramic style in Segu’s heartland corroborate historical traditions on the emergence of a unitary state during this period.7

Biton Kulubaly’s death resulted in a brief disintegration of his nascent state, as neither of his two sons, Dekuru and Bakari, was able to hold power for long. According to a chronicle of Walata —an ancient trading town in what is today southern Mauritania, the Kulubaly dynasty was ultimately ended by Bakari's death at the hands of the slave warriors originally appointed by Biton. These took on the title "ton-tigi" and carved out their own rival kingdoms.8

The tomb of Biton Mamary Coulibaly, founder of the Segu Empire, in Segoukoro (old Segou), next to a recent reconstruction of his palace with its seven vestibules.

Around 1766, N’golo Diara, one of the crown slaves who had been appointed as guardian of the four cults of Segu, used his office to call a meeting of other slave warriors at the central religious shrine of Segu. He detained them and forced them to acknowledge him as ruler with the military title of faama. Ngolo institutionalized his new power by reorganizing and rebuilding the army, which he used to reconquer much of the lost territory and establish a new capital at Segu-sikoro.9

N’golo retained the key social institution of the ton-jon or association of ‘submitted’ persons who constituted the army and much of the bureaucracy. These men, originally captured in war (much like the Mamluks and Ottoman janissaries of the Islamic world), were incorporated into regiments stationed at key locations in the middle valley. Some acceded in time to the post of regimental commander, which meant active participation in the highest councils of the state, where the succession to the throne was decided.10

An account by the traveller Mungo Park, who passed through Segu’s domains twice in 1796 and 1805, describes some of the early battles fought by N’golo to re-conquer the lost territories and walled towns led by rival warrior chiefs. N’golo then established the new Diara dynasty by appointing his sons as provincial governors. He expanded the borders of his state rapidly, against the Senufo in the south, the Mossi in the east, and the Dyula towns of Côte d'Ivoire. He later hosted the exiled ruler of Mossi, Naba Kango, and provided him with a Bambara mercenary army to reclaim his throne.11

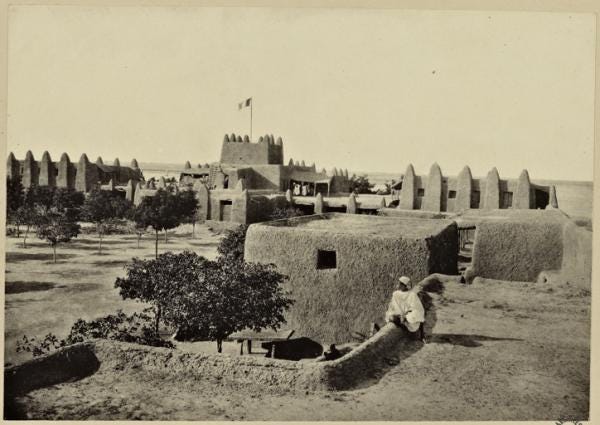

Park also included a description of the capital, most of whose development at the time could be attributed to the reign of N’golo Diarra:

“Sego, the capital of Bambarra, consists of four distinct towns ; two on the northern bank of the Niger, called Sego Korro, and Sego Boo ; and two on the southern bank, called Sego Soo Korro, and Sego See Korro. They are all surrounded with high mud walls ; the houses are built of clay, of a square form, with flat roofs ; some of them have two stories, and many of them are white-washed. Besides these buildings, Moorish mosques are Seen in every quarter ; and the streets, though narrow, are broad enough for every useful purpose.”12

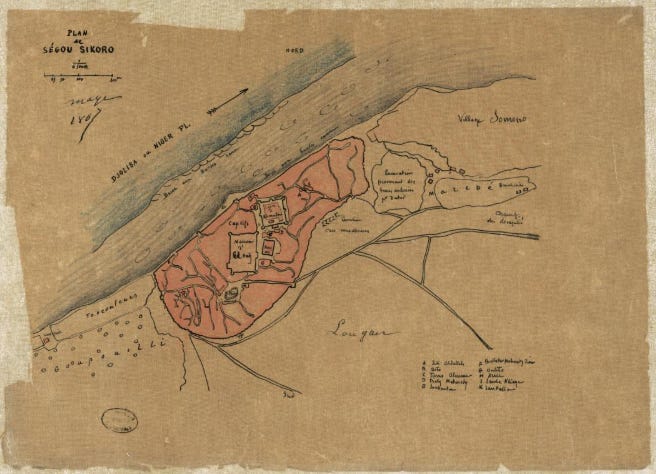

Map of Segu Sikoro by Eugene Mage, ca. 1867.13

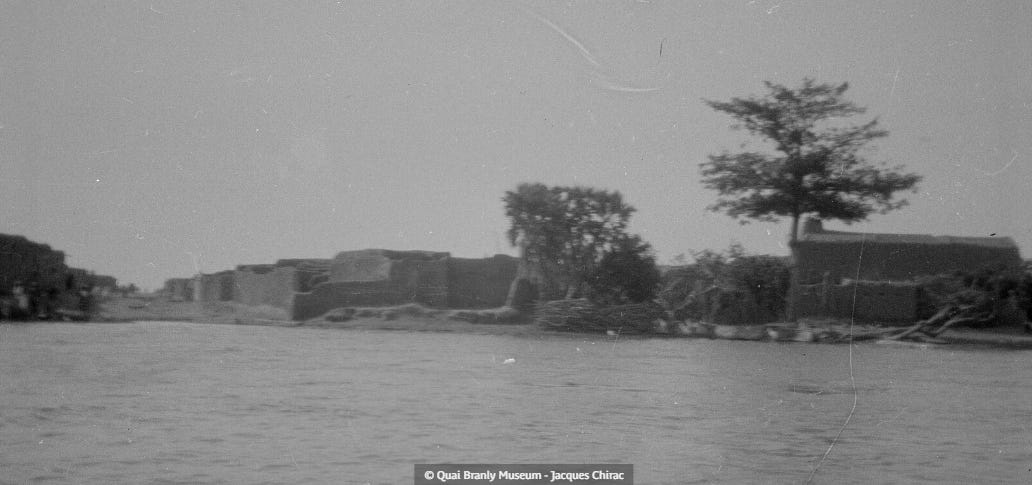

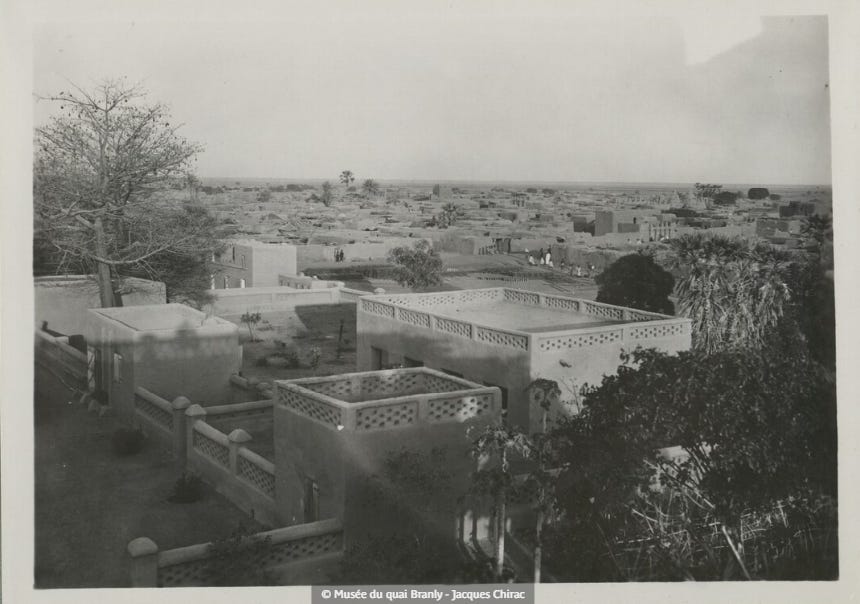

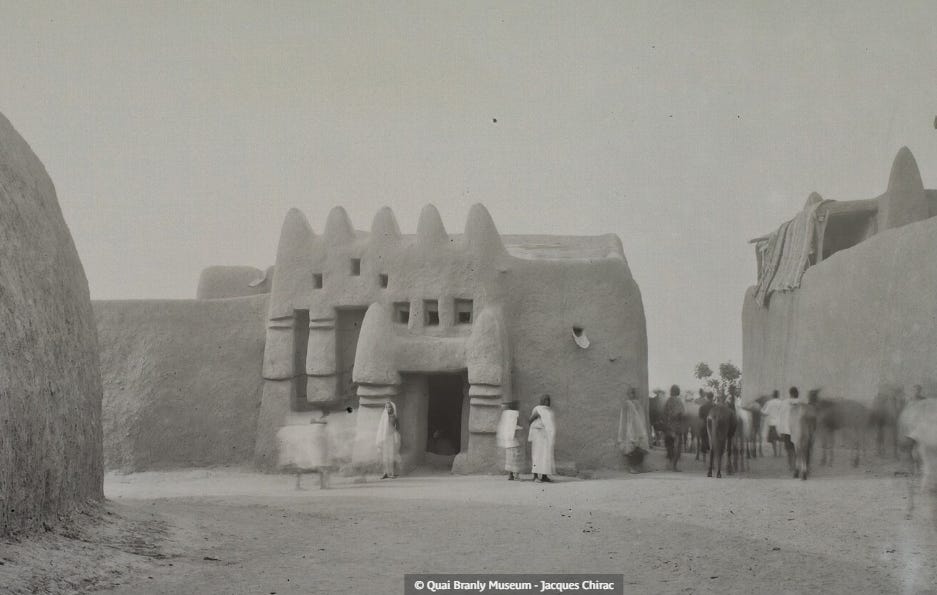

The walls of Segu seen from the river. ca. 1883-1888. Quai Branly.

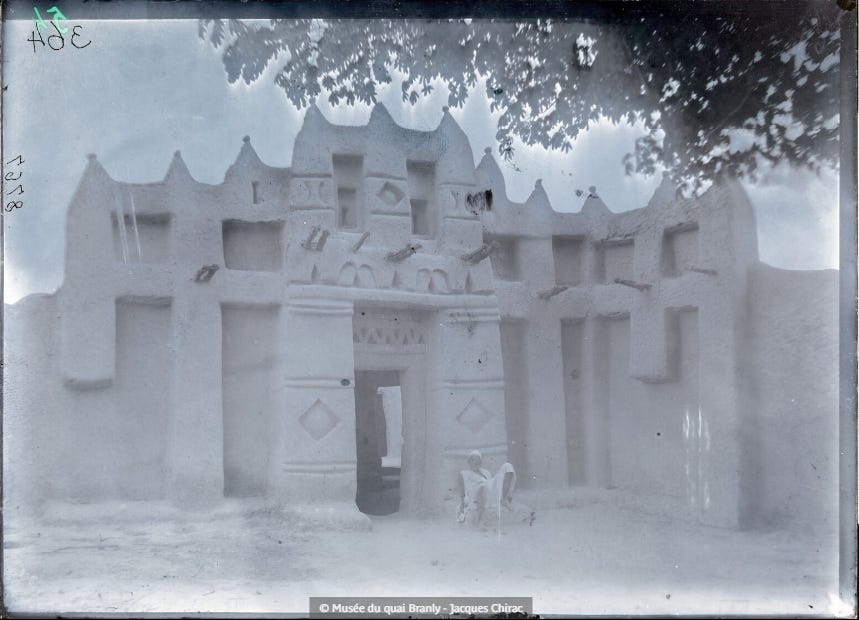

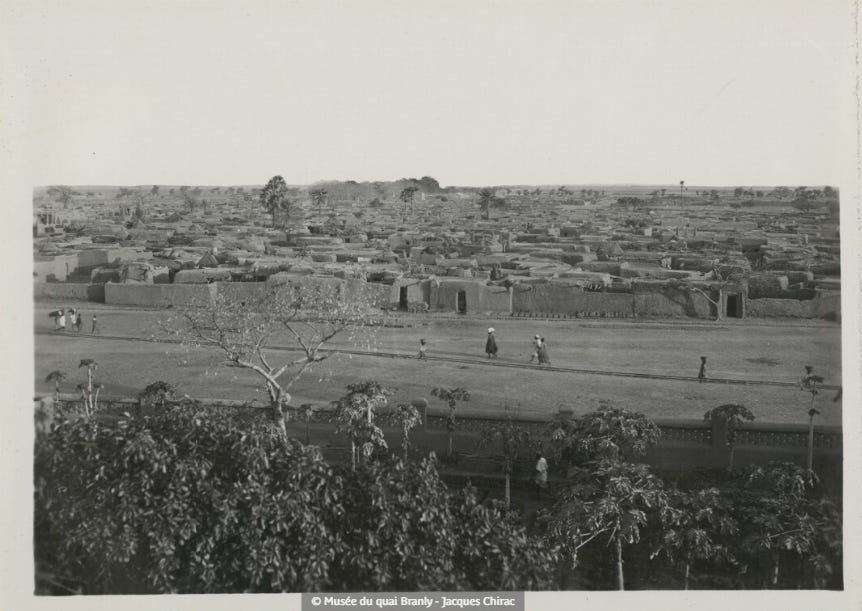

street in Segu, Mali. ca. 1930. Quai Branly

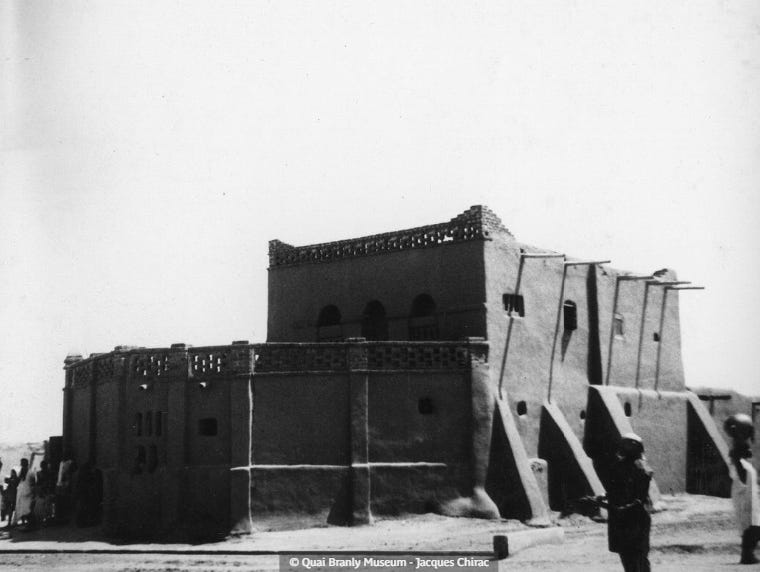

Segu, Mali. ca. 1930. Quai Branly.

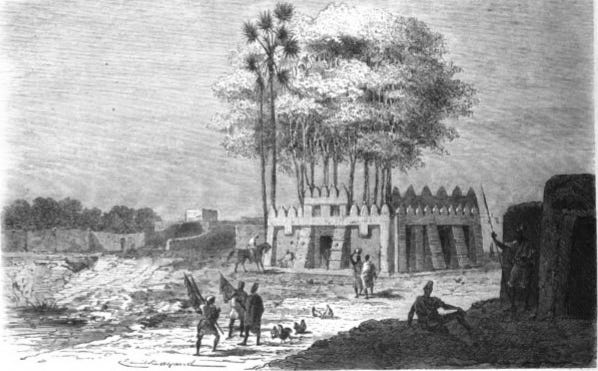

walled settlement of the Bambara on the road to Ségu. ca. 1883-1888 Quai Branly

N’golo was succeeded in 1790 by Mansong/Monzon, who had allied with the rich Marka merchants of the trading towns to defeat rival candidates. In 1796, Mungo Park observed that Djenne was nominally a part of the king of Bambara's dominions, with a governor appointed by Mansong. He added that the people of Massina (in the north-east of Djenne) also paid “an annual tribute to the king of Bambara, for the lands which they occupy.” He also reports on the frontier wars between Segu and the Mosi kingdom of Yatenga, whose armies briefly reached Djenne.14

In the last decades of the 18th century, the region of Massina, which was dominated by Fulbe herders (later known as the Masinanke), came within the orbit of the Bambara empire of Segu. The Fulbe aristocracy of warriors known as the Dikko arɗos of Masina spent time in Segu, collected taxes for the Bambara kings, participated in their campaigns, and intermarried. They ruled the area up to the Bandiagara cliff on behalf of the kings of Segu.15

In his second visit, Mungo Park noted that Timbuktu was taken by Masong's armies in 1800: “The king of Bambara... proceeded from Sego to Timbuktu with a numerous army, and took the government entirely into his own hands, permitting the Moors to remain under his protection, and for purposes of trade.”

Monzon promised Park safe passage throughout all his domains: “that a road is open for you everywhere, as far as his land extends. If you wish to go east, no one shall harm you from Segu until you pass Timbuktu. If you go west, you may travel through Foladoo and Manding, through Kassan and Bundu; the name of Monzon’s stranger will be sufficient protection for you.”16

House of the daughter of Mansong Diarra (ruler of the Bambara Empire 1795 to 1808) in Yamina, Mali. ca. 1868, Engraving by Eugene Mage.

State and Society in Segu

The territorial expansion of the Bambara state of Segu was not accompanied by an administrative reorganization resembling that of the imperial Mali or Songhai states. Biton and his successors adopted the military title faama, rather than the imperial title of mansa. The Bambara rulers remained war chiefs, whose authority was imposed and maintained by force of arms. Their power was based on the effective organization of the ton, through which tribute was collected from conquered groups, labour was organized, and leaders were elected.17

The state instituted a system of taxation to supplement revenues collected from expansion. A fixed amount of cowries, livestock, trade goods, and captives was collected from conquered regions. Certain groups paid higher taxes, notably the Marka towns, which paid taxes regularly—to demonstrate their good faith and guarantee their access to state markets and routes.18

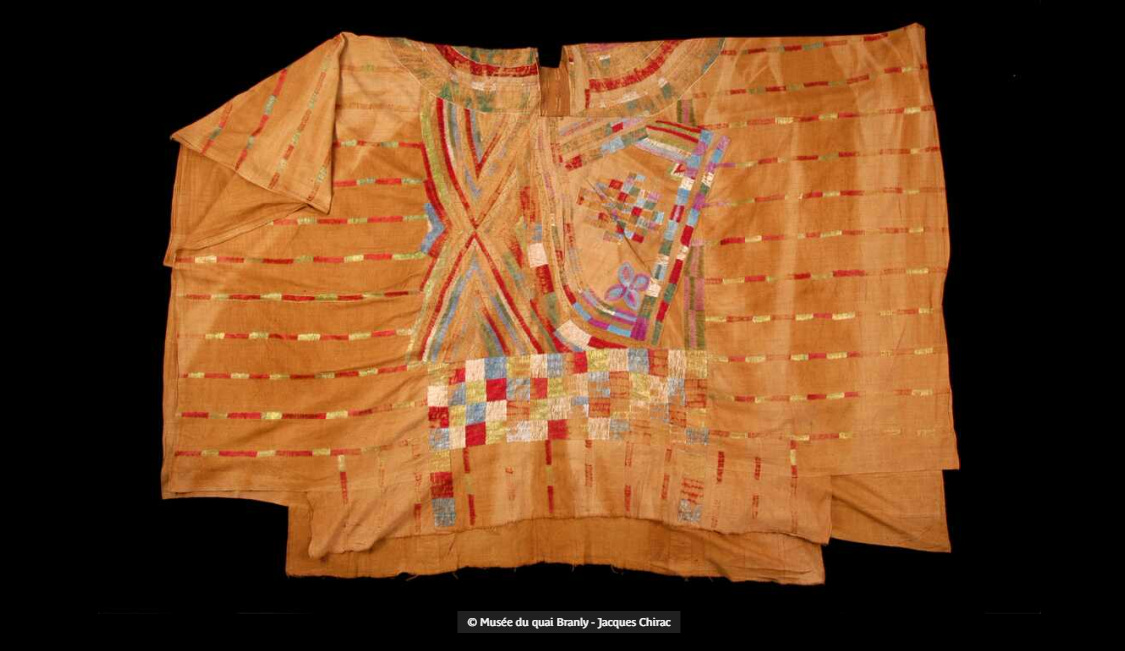

Segu's ruling class retained the traditional religions of the Bambara, practising rituals associated with traditions of farming, hunting, and war. Segu religion was a system of practices and beliefs nurtured by a professional clergy, over and above the diverse observances at the local level. It was within this religious context that much of the ‘Bambara artwork’ found in Western museums today was originally produced. The king played a leading role in religious ceremonies attached to the annual productive cycle and maintained temples and priests at court and in important villages.19

Although they practiced traditional religions, the Segu kings also took part in Muslim festivals and patronised marabouts (scholars), identified in historical traditions as the Marka. The Marka vs Bambara ethnonym dichotomy distinguished those who are Muslim and those who are not. The Marka were thus as ethnically heterogeneous as the Bambara, encompassing several ancient social groups in the region that were historically associated with long-distance trade and Islam, such as the Soninke/Wangara/Dyula.20

Traditions credit the Diara kings of Segu with placing all the Marka commercial towns under direct state protection and encouraging the corresponding increase in Muslim influence in Segu’s administration. During his second visit in 1805, Mungo Park was informed that “Modibinne is Monzon’s prime minister; he is a Mohammaden, but not intolerant in his principles.” He also noted that in Segu, “Moorish mosques are seen in every quarter,” and made a similar observation in the neighbouring state of Kaarta, where he noted the syncretic nature of Islam among the Bambara, who comprised the largest number of worshippers at these mosques.21

Political events influenced the volume of the trade and the spatial dimension of regional markets and routes, especially the two main towns of Nyamina and Sinsani.

In the early 19th century, Nyamina was a significant point of contact for Saharan traders, local Soninke and Bambara merchants, and Dyula traders of various origins, driving their caravans from as far south as Kankan (present-day Guinea). A manuscript from the town of Tichitt (in southern Mauritania), dated to the 1840s, mentions that Nyamina was the southernmost entrepot visited by Saharan traders.22

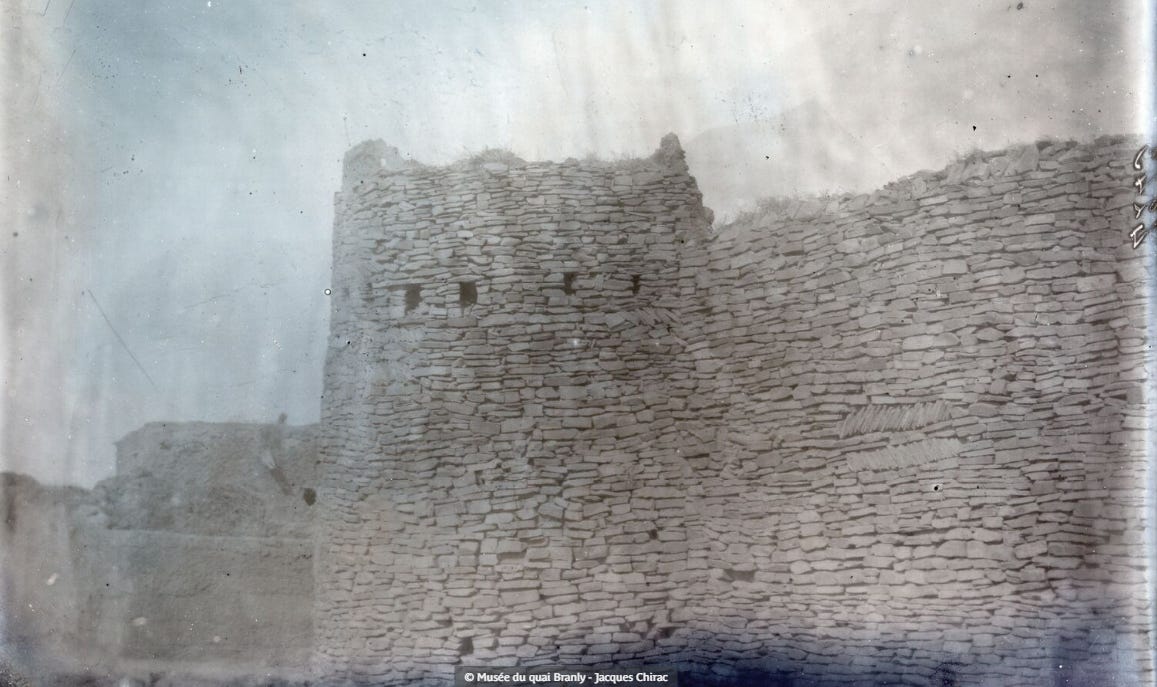

Walls of Nyamina, Mali. ca. 1883-1888. Quai Branly

walled gate to a house in Nyamina, Mali. ca. 1880-1889. Quai branly

Sinsani appears to have been the main commercial hub during the Seguvian period. Mungo Park visited Sinsani twice in 1796 and 1805, noting the dominance of the Muslim traders who initially objected to his presence during his first visit, but were later compelled to accept it during the second visit after he received official recognition as faama Monzon’s “stranger” (ie, protected guest).

Sinsani market impressed Park considerably:

“Sansanding contains, according to Koontie Mamadie’s account, eleven thousand inhabitants. It has no public buildings, except the mosques, two of which, though built of mud, are by no means inelegant. The market is crowded with people from morning to night: some of the stalls contain nothing but beads; others indigo in balls; others wood ashes in balls; others Hausa and Jenne cloth. I observed one stall with nothing but antimony in small bits; another with sulfur, and a third with copper and silver rings and bracelets. In the house fronting the square is sold, scarlet, amber, silks from Morocco, and tobacco, which looks like Levant Tobacco, and comes by way of Timbuktu.”23

walled entrance to the palace of Mademba, Sansanding, Mali ca. 1900, BnF, Paris

Besides the two main towns of Nyamina and Sinsani, another important settlement was San, which was one of the first towns captured by the rulers of Segu. Around 1754, it was attacked by the armies of Kong and briefly abandoned. It was later repopulated by the old inhabitants, as well as new groups, forming a mixed community of Marka, Bozo, and Traore, all of whom mostly spoke Bambara. However, the town didn't become a major trade hub until the late 19th century, likely diverting some of the trade from Sinsani and Nyamina, which suffered the brunt of al-Hajj Umar’s attacks in the latter half of the century..24

The walled town of San, Mali. ca. 1930-1939. Quai Branly

External trade was oriented towards three regions: the southern forest zone, the Senegambia region, and southern Mauritania, each of which followed different routes, some extending as far south as Sierra Leone. Interestingly, the first reference to a trader who identified himself as Bambara comes from Free Town in 1854. The writer Sigismund Koelle mentions a “Bámbara , or Bámbaran — from Fúrēkaba , born in the well-known region of Ségou . . . where he lived to about his thirtieth year , when he went to Gambia as a trader , and after two years stay there to Sierra Leone.”25

Regional trade was conducted along several routes and involved a broad range of commodities and other trade goods, many of which were sourced locally.

Marka traders exchanged locally produced indigo-dyed cloth, salt, gold, horses, kola, grain, and captives, to and between the forest edge entrepôts of Kankan, Sikasso, Bobo Diolasso, Odienne, and Tengrela. They also controlled the desert side routes to the southern Mauritanian towns of Tichitt and Walata, bringing salt from Idjil and Taodeni, as well as the export trade to European forts in the Senegambia, where they traded the same products in exchange for firearms and other imports.26

The overland trade was conducted using caravans, which were relatively small groups of about 30-40 traders led by a kulukuntigi (Bambara: kulu, caravan; kuntigi, leader), transporting an assortment of goods on the backs of donkeys or pack oxen. While well armed, the caravan was no match for state armies and often had to request permission from the latter. Caravan leaders paid the necessary tolls for the right to cross territories safely, and at times acted as unofficial informants/emissaries of the Segu kings.27

Dyed cotton tunic (boubou) from Segu, Mali. 19th century. Quai Branly

Merchants also transported goods by river using large canoes/barges, which facilitated the movement of bulky cargoes over long distances. This led to an important opening for the surplus grains produced on Marka plantations that were exported north to Timbuktu.

The advantages of riverine transport were considerable. In the late 19th century, Felix Dubois estimated that an average 20- to 30-ton freight canoe on the Niger could transport as much produce as a caravan of 1,000 porters, 200 camels, or 300 pack oxen. Freight canoes cost between 200,000 and 300,000 cowries, passage from Djenne to Timbuktu costs 1,250 cowries, and a 100-kilogram load travelled the same route for 1,500 cowries.28

In the 1820s, René Caillie travelled on board one of these large barges from Djenne to Timbuktu . It had a capacity of 60 tons and was sheltered with matting. He observed that there were always about flotillas of 80 such barges plying the route between Jenne and Timbuktu. Each had a capacity of 60-80 tons, measured about 100ft long and 12-14ft broad, with a crew of 16-18, including the captain, and could accommodate more than 50 other passengers with their animals. These barges are made by stitching large planks together at the side using a rope, and the stitching holes are caulked with a local binding concoction. Wooden bars are laid at the bottom, but leave a trough in the middle from where leaking water is bailed. Other wooden bars are raised to form a 3ft high deck, and there was a section for cooking as well as enough room for bailers to work in 6-hour shifts, and for the crew to move around the barge, since it was steered with poles and paddles.

[ see my previous essay on the history of Navigation along the Niger River ]

The bulk of the riverine trade was handled by the Somono, whose origins and social organization were closely associated with the operation of the Seguvian political system. While primarily identified as waterfolk, the Somono, like all social groups in Segu, occupied several levels of social status, ranging from dignitaries to warriors, tradesmen, clerics, weavers, and masons.

The Somono were a heterogeneous group composed of Soninke, Bambara, Malinke, Minianka, Bozo, and other groups, most of whom spoke Bambara and later adopted Islam. They were centered in the heartland of the Middle Niger valley around Segu but established settlements from Nyamina to Sinsani, ferrying passengers, armies and goods, while collecting taxes for the kings at Segu.29

An account by Eugene Mage, who utilized the services of the Somono while traveling along the Niger in 1863, mentions that the Somono were subjugated by the Segu kings, for whom they made canoes. While he was writing at the start of the Umarian period, he mentions that their function had begun during the Segu period.

“The Somono expanded along the littoral, forming in each village a type of corporation, which lives apart, works, and transports [goods and people] by canoes, of which they have a monopoly, and which provides them with many cowries… Each of our canoes received a skipper and two crew members at Nyamina; besides, at each village one gets a [new] crew, which thus relays from station to station.”30

The common house of the somonos of Ségou. ca. 1868, Engraving by Eugene Mage.

Residence of the chief of the Somono in Segu, Mali. ca. 1946. Quai Branly.

A barge near Naymina, Mali. ca. 1899. ANOM

A barge at Kabara, the port of Timbuktu, Mali. ca. 1920-1939 ANOM

The availability of both good transport and a steady market for locally produced commodities stimulated regional travel and economic growth that had far-reaching implications for the structure of the Seguvian social formation.

The diversity and fluidity of the different population groups reveals the complexities of social identities in 18th/19th-century Segu. The Bambara, Marka, and Somono have a shared political history, but did not constitute ‘tribes’ living on well-defined territories with specific occupations. The three ethnonyms were used as sociopolitical categories which shaped (and were shaped by) the development of the state at Segu.

Collapse:

The dominance of the warrior elite in Segu also meant that the king could only control the centrifugal tendencies among warriors by monopolizing resources and institutions for warfare and by rewarding warriors with booty/loot from campaigns on the frontier. Segu's kings nominated slave warrior chiefs as leaders of regiments and as administrators of conquered territories. Livestock, trade goods, dependants, and captives obtained in warfare were redistributed among the title holders after each campaign.31

Traditional accounts about the reign of Da Monzon (1808-26), who ruled the empire at its height, recounted how he fielded 100,000 soldiers. More realistic estimates indicate that the Segu could field no more than 15-20,000 soldiers for the largest battles. The bulk of these fought on foot, but there were also cavalry units, as well as war canoes used to transport soldiers and raid riverine settlements.32

By the middle of the 19th century, the empire of Segu had lost some of its lustre. In the 1820s, its Masina tributary had asserted its independence and cut off the northern trade to Timbuktu, while the Tamba state emerged in the southwest and cut into Bambara tribute from the upper Niger. Diminished success in warfare meant less reward and advancement for the tonjon who organized behind various Jarra brothers and competing factions.33

After the reign of Cefolo (1827-1839), five kings reigned in close succession between 1839 and 1858 until the ascendence of Bina Ali (1858-1861).

Bina Ali came to power after the tonjon had overthrown his predecessor Torokoro Mari for favouring the Muslim faction at the court. This faction had compelled the king to send an embassy to the reformist leader al-Hajj Umar Tal, while the latter's forces were campaigning in Segu's westernmost territories. Bina Ali was thus tasked with organising a military response to al-Hajj Umar's movement, beginning with the siege of Nioro in 1859.34

Bina Ali spent most of his brief reign facing off with the armies of al-Hajj Umar, but the superior weaponry of the latter often turned the battles in their favor. Umar captured Nyamina in June 1860, used his cannon to breach the walls of Woitala in September, and moved into Sinsani by the end of the year. Having lost most of his army, Bina Ali was forced into an alliance of convenience with the Massina ruler Ahmadu III, in order to undermine Umar's religious pretext for waging a ‘holy war’ against Segu.35

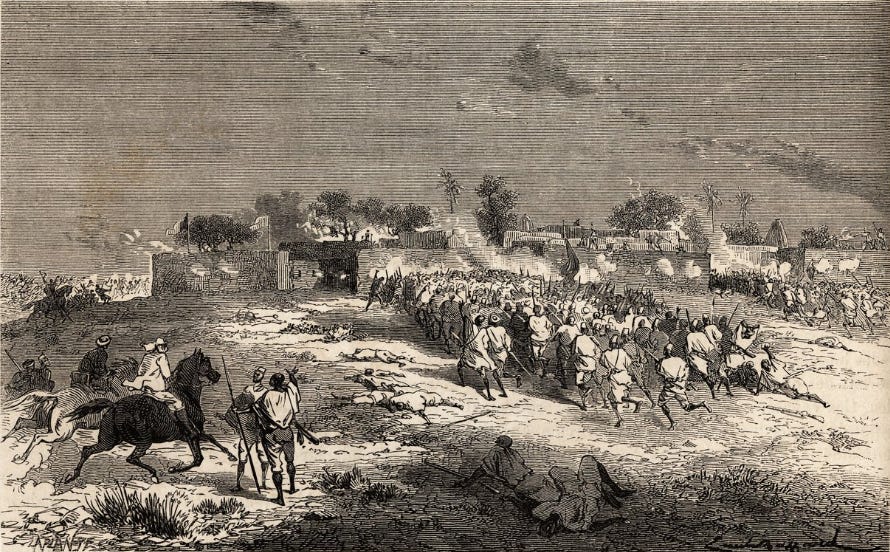

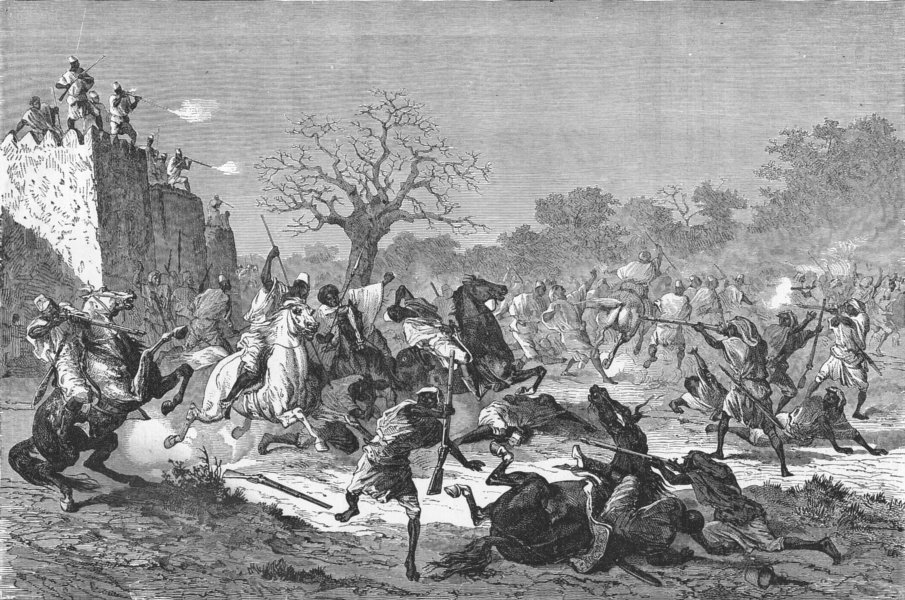

Engravings from 1868 depicting Umar Tal’s attack on the walled town of Sansanding, and the defense of the city by its Bambara and Somono residents. (Top) Attaque de la pointe des Somonos à Sansandig by Eugène Mage. (Bottom) ‘The Bambaras attack the Besiegers’ by Henry Walter Bates

al-Hajj Umar’s fortress at Nioro, Mali. ca. 1883-1888. Quai Branly

After a series of diplomatic exchanges and intellectual debates between al-Hajj Umar and Ahmadu, the two sides prepared for battle. In February 1861, Umar’s army crushed the Bambara and Masina forces at Tio near Sinsani, forcing Bina Ali to flee from his capital. At Segu, Umar found the Jara storehouses full of treasure, which he distributed among his army. The rest of the Seguvian administration surrendered to Umar, marking the end of the empire.36

Al-Hajj Umar and his successors restored the walls of the city and built a new palace and several mosques. He retained some of the sculptural artworks of the Bambara kings as evidence of their continued practice of their traditional religions (contrary to the claims of their Masina allies). While most groups initially surrendered, the death of al-Hajj Umar sparked rebellions among most of the Bambara, Somono, and Marka, ultimately weakening the nascent empire just before the colonial scramble.

House of a notable in Segu, Mali. ca. 1883-1888. Quai Branly

Mosque of al-Hajj Umar in Segu, Mali. ca. 1930. Quai Branly

The old palace of Ahmadu, son of al-Hajj Umar, in Segu, Mali. ca. 1895. ANOM.

In 1881, a West African oil trader from the Gold Coast (Ghana) named John E. Ocansey visited the port city of Liverpool to collect a bad debt of £2,678 ( about £416,000 today) from an English trader.

My latest Patreon article reproduces the full autobiographical work of John E. Ocansey and explores the commercial links between the Gold Coast and England in the late 19th century.

Please subscribe to read about it here, and support this newsletter:

History, Archaeology, and Bambara Origins”, by Kevin C. MacDonald in Ethnic Ambiguity and the African Past: Materiality, History, and the Shaping of Cultural Identities, edited by François G. Richard and Kevin C. MacDonald.

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg 14-15, 128-129, 135, 138, 193,194)

Les épopées d'Afrique noire by Kesteloot, Lilyan, Dieng, Bassirou pg 159-192, Ethnic Ambiguity and the African Past: Materiality, History, and the Shaping of Cultural Identities, edited by François G. Richard and Kevin C. MacDonald, pg 128-130, The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4, pg 174-175

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 28-34, The Early State in African Perspective: Culture, Power and Division of Labor edited by Shmuel Eisenstadt and Naomi Chazan, pg 103

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4, pg 175, Dyula and Sonongui Roles in the Islamization of the Region of Kong by Kathryn L Green in ‘Asian and African Studies. Volume: 20’

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 42,

Ethnic Ambiguity and the African Past: Materiality, History, and the Shaping of Cultural Identities, edited by François G. Richard and Kevin C. MacDonald, pg 133-140

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4, pg 176-177

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 43, Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century By Unesco, pg 169

The Holy War of Umar Tal: The Western Sudan in the Mid-nineteenth Century by David Robinson, pg 245, The Politics of Islam in the Sahel: Between Persuasion and Violence by Rahmane Idrissa, pg 148-149

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 44

Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa by Mungo Park

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara by Alisa LaGamma, pg 223

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4, pg 178, 186

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4, pg 164, Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith: Aḥmad Lobbo, the Tārīkh al-fattāsh and the Making of an Islamic State in West Africa by Mauro Nobili, pg 128-129, 149, 200.

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 45, The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4 pg 178.

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume ,4 pg 178-179, Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century By Unesco pg 170-171

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 40

The Holy War of Umar Tal: The Western Sudan in the Mid-nineteenth Century by David Robinson, pg 246, Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara By Alisa LaGamma, pg 226-247

Ethnic Ambiguity and the African Past: Materiality, History, and the Shaping of Cultural Identities, edited by François G. Richard and Kevin C. MacDonald, pg 119, 129, The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4, pg 193

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4, pg 193, Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 46.

On Trans-Saharan Trails: Islamic Law, Trade Networks, and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Nineteenth-Century Western Africa by Ghislaine Lydon, pg 157

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts by pg 50-51

Une ville de la République du Soudan : San by Kamian Bakari, San and the Sanké: A History of a Marka-Malinke Trading City on the Niger by Andreas W. Massing

Ethnic Ambiguity and the African Past: Materiality, History, and the Shaping of Cultural Identities, edited by François G. Richard and Kevin C. MacDonald, pg 121

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 60-61, The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4 pg 181

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 47-50, 63-64

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 73-75

Somono Bala of the Upper Niger: River people, Charismatic Bards, and Mischievous Music in a West African Culture by Daniel Harrington, pg 4-28, Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 69, 72

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 70, 72

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 35-39

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914 by Richard L. Roberts, pg 36

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith: Aḥmad Lobbo, the Tārīkh al-fattāsh and the Making of an Islamic State in West Africa by Mauro Nobili, pg 9-11, The Holy War of Umar Tal: The Western Sudan in the Mid-nineteenth Century by David Robinson, pg 246-247

The Holy War of Umar Tal: The Western Sudan in the Mid-nineteenth Century by David Robinson, pg 247-248

The Holy War of Umar Tal: The Western Sudan in the Mid-nineteenth Century by David Robinson, pg 257-262

The Holy War of Umar Tal: The Western Sudan in the Mid-nineteenth Century by David Robinson, pg 263-273

I loved reading this piece. What fantastic work. Thank you very much for shedding light on the history of this region.

Great work.

Very overlooked part of African History.