The fall of Songhai to Morrocco in 1591 was succeeded by a over a century of political and social upheaval in west Africa, the Niger River Valley from Jenne to Timbuktu - which comprised the old core of the medial empires of Ghana, Mali and Songhai- became a backwater while the previously peripheral regions in what was Songhai's southwest and south eastern flanks become the new centers of wealth and heartlands for the succeeding states. The Moroccan empire which briefly succeeded Songhai had effectively pulled out of the entire region after 16121 following its failure to pacify the region beyond the principal cities; effectively making 1591 an pyrrhic victory that "swallowed up both the conqueror and the conquered"2, a period of internecine warfare erupted across the region as the now-independent provinces and periphery states sought to consolidate their power, culminating with the rise of the empire of Segu under Bitòn Coulibaly in 1712 (in what were formerly Songhai's south western provinces) and the re-establishment of independent Hausa city-states (in what were formerly Songhai's south-eastern peripheries); a process that was completed by 1700AD.3

The principal Hausa city-state during this time was Kano, the capital had a population of over 40,000 a vibrant handicraft industry in textiles and leatherworks, it controlled a territory about 60,000 sqkm large and engaged in extensive trade with west Africa and north Africa. Kano had been effectively independent by the end of the reign of its ruler (Sarki) Kisoke (r. 1509-1565AD) who'd ended the tributary relationship it had with the empires of Kanem-bornu and Songhai (plus its offshoot of Kanta). The city state controlled a bevy of towns such as Gaya, Rano, Karaye, Dutse and Gwaram, it had a heterogeneous population dominated by Muslim Hausa but with significant proportions of traditionalist Hausa (Maguzawa) as well as non-Hausa minorities such as the Fulani, the Kanuri, the Wangara (Dyula), the Yoruba and seasonal traders from its north like the Turegs, maghrebian Berbers and Arabs. Kano was run by a quasi-republican system of government in which power oscillated between the state council comprised mostly of non-royal hereditary and appointed officials versus the King himself, the latter of whom was elected by four senior members of the state council and his powers over administration were restrained depending on the power of the sitting council members.4

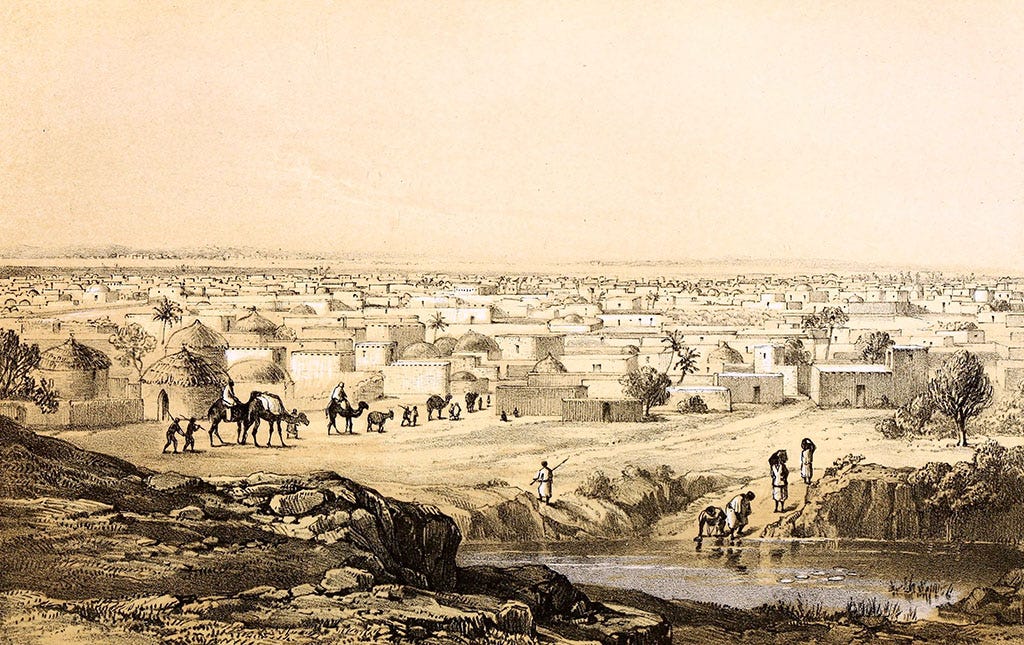

painting of Kano from Mount Dala by H. Barth, 1857

Kano's political and social structure was largely Islamized by the 16th century, the religion had been adopted formally as early as the 14th century during Sarki Yaji I's reign (r. 1349-1385AD) following a period of extensive relations with the Wangara of the Mali empire and the immigration of this group to the Hausalands that may have also involved a brief conquest at Kano and Katsina.5 Yaji I appointed many of these Wangara to prominent positions such as Muezzin and judge and the religion was impressed on his subjects who now observed the obligatory prayers6, however as with all state-imposed social orders, the new religion was observed with varying degrees in practice which allowed for brief returns of secularization that occasionally accommodated traditionalist elements as power swayed between the deposed traditionalists and the increasing Islamized court and officials, therefore, there were long periods of rule under devout Muslims interspaced with periods of rule where traditionalist influence was significant, the most notable devout rulers were the Sarkis; Yaji I (r.1359-1385), Rumfa (r. 1463 -1499), Zaki (r. 1582-1618) and Alwali II himself (r.1781–1807), including some who went as far as resigning to concentrate on their quranic studies eg Sarki Umaru (r. 1410-1421) and Sarki Kado (r. 1565-1573) about whom it was written that he "did nothing but religious offices, he disdained the duties of the Sarki, he and all his chiefs spent their time in prayer"7.These were interspaced with periods when traditionalists influenced the royal court and gained the upper hand such as the Cibiri cult under Sarki kanejeji (r. 1390-1410AD)8, and the charms used by Sarki Kukuna in (1652-1660AD)9, and chibiri and bundu cults under Sarki Dadi (1670-1703AD)10. This sort of pluralist Islam was a characteristic of states with Dyula Islam which was brought into Kano (and most of west Africa) by the Wangara (a catchall term for the Soninke and Malinke diaspora from the Mali empire).

Central to Dyula islam are the pedagogical traditions of Al Hajj Salim Suwari, a prominent scholar of Soninke origin living in the late 15th century and early 16th century who taught several notable west African scholars active in the Mali and Songhai empires, Salim belonged to a dominant school of thought among the Wangara that was concerned with principals guiding the interactions between Muslims and non Muslims. The central theme of these principles was an aversion towards armed conversion (eg through jihad) except in self-defense, because unbelief was interpreted by this school as a product of ignorance rather than wickedness; that it was God's design for some people to remain unbelievers longer than others, and that Muslims may accept the authority of a non-Muslim ruler if that ruler enables them to follow their religion11. Suwari's school of thought was a product of the political realities of west Africa during this time, when traditionalist forces were powerful and Muslims constituted a small minority (albeit influential). it was carried by Wangara traders and scholars across west Africa but especially to the Hausalands where they comprised an influential merchant and scholarly class in the cities of Katsina and Kano, their Dyula Islam was urban based, associated largely with the elite and royal courts and supported by the long distance trade in gold of which the wangara were famous. One such immigrant was Abd al-Rahman Zaghaite who arrived in the Kano in the late 15th century according to the Wangara chronicle. This “accommodative” Islam held sway over the more orthodox teachings especially those of the northafrican scholar al-Maghili who had visited Kano and Katsina in the late 15th century and advocated for more radical reforms of the political and social systems of the state to be more in line with Islamic principles and insisted that the only association between Muslims and non-coverts was jihad.12 This pluralist state of affairs lasted until the 18th century when a revolution swept across westafrica beginning with Nasir al-Din's movement in the senegambia region who primarily directed it against the Hassaniya Arabs of southern Mauritania and also against the Senegambian African states the latter of whom he claimed offered little protection for their citizens from the former’s raids. The teachings of Nasir and his followers were relatively more in line with al-Maghili's and in opposition to the predominant Dyula teaching in the region.

The decades from 1770 to 1840 AD have been characterized by various world history scholars as the "age of revolutions", a historical construct used to highlight the period of rapid political and social transformation in western Europe and the Atlantic world. In Africa, this period was marked by the fall of several old states to the growing power of village-based transhumant scholarly groups whose call for political reform directed against the elites of the Senegambia region was couched in the language of jihad, this begun with Nasir al-Din in 1673 a Berber cleric who rallied a diverse group of followers from Wolof and Torodbe-Fulani groups against intrusive nomadic Arab groups north of Senegal river and against the African rulers of the kingdoms south of the river, his movement was ephemeral but the scholarly groups associated with it spread it across the region founding the states of Futa Bundu in 1699, Futa Jalon in 1727, Futa Toro in 1769 and Sokoto in 180413, it was the latter that subsumed Kano which was at the time led by Sarki Alwali II (r. 1781-1807).

As the first Hausa city-state to fall to the revolution, Kano under the reign of Alwali has been the focus of studies on the revolution age in west Africa. This article looks at the social political organization of Alwali's Kano on the twilight of the 800-year old Bagauda Dynasty.

Kano cityscape in the early 20th century

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

State and society under Alwali II (r. 1781-1807)

Political structure and governance in Kano

The main authority in the Kano government lay with the Sarki (ruler) and the Kano state council (Tara ta Kano) comprised of nine senior officials; the Madaki, Sarkin Bai, Dan Iya Wambai, Makama, Galdima, Sarkin Dawaki and the Tsakar Gida, the first four were electors who appointed the successor on the death of the Sarki and their advice on official matters was not to be overuled by the Sarki, they were therefore the highest forum of the state and its final deliberative organ.14 The power of the council was counteracted by the Sarki through expanding his executive authority by creating offices of senior and powerful slave officials such as the Shamaki, Dan Rimi, Sarkin Dogarai, etc as well as elevating dynastic offices such as the Ciroma. While government power had been oscillating between both the Sarki and the council for centuries, the continuous expansion of executive powers created differing lines of communication and effectively centralized authority around the Sarki at the expense of the council, the pinnacle of this centralization was attained by Sarki Zaki (r. 1768-1776) and continued by his successors including Alwali II.15

Below this was a lattice of dozens of administrative offices with varying levels of seniority and authority, differentiated by various criteria such as; hereditary or appointed, royal or non royal, resident in the capital or outside the capital, military or civil, secular or religious. The most influential of these offices were the dynastic offices reserved for the ruler's kin such as the Ciroma (crown prince) and the fief holders (Hakimai) who were directly under the authority of the Sarki16. The state had courts both at the capital and regional courts all of which were presided over by a judge (Alkali) and the appointed provincial judges (Alkalai), the law administered in Kano was a mixture of Hausa law (al'ada) and Muslim law, these judges (and rural chiefs) were also incharge of local prisons and police staff17.

Kano under Alwali II was an expanding polity, incorporating formerly independent chiefdoms as subordinate components, he is credited with subsuming the chiefdom of Birni Kudu, which was then added to the dozens of statelets that had long been conquered by Kano such as Rano, Gaya, Dutse, Karaye and Burumburum.18

Kano and its neighbors in 1780

Kano’s expansion was enabled by its military, its strength primarily lay with its cavalry whose horses, armor and mounted soldiers were provided by the Hakimai while war campaigns were planned by the Sarki and the city council19 But as Kano faced increasing Jukun predations in the 17th century and the council-controlled military proved impotent to defend the city whose walls were breached thrice and whose army attimes abandoned the Sarki in the midst of battle, later Sarkis sought to bring the military under their direct control such that by Sarki Zaki's reign (r.1768-1776) Kano’s army included an elite force of musketeers and was developing into what historian Toby green termed a "fiscal military state": collecting revenues to pay a standing army, this extended Kano's influence across west africa such that by the 1770s, Kano had to confirm the appointment of a new ruler in Timbuktu.20, due to the constrained supplies of muskets however, none were mentioned by Alwali' IIs time but the Army was by then effectively under the Sarki’s control.

The walls of kano

Trade and economy in Kano.

Kano in the late 18th century was one of the most prosperous and largest cities in west africa, within the city's walls were about 40,000 people engaged in all kinds of crafts industries, farming and trading activities, the city-state provided an attractive market for visiting merchants owing to its strategic position along the main trans-west African and Transaharan caravan trade routes

The caravan trade was closely regulated by Alwali' IIs government, first by securing the major routes within its territory through building fortified towns along these routes, garrisoning the perimeter against bands of Tuareg raiders, sinking wells, and encouraging settlements and small markets to provision caravans along the routes. On arrival, the caravan was met by the Sarkin Zago (an official incharge of supplies and accommodation), unloading their camels at the Kofar Ruwa gate and showing the guests to well-built hostels where they would be housed (rent) during the course of their stay, the hostel owner also acted as their broker/trading agent who itemized their goods, change their currencies, buy provisions and was provided a minimum price above which he was allowed to retain the profit, while credit and warehousing services were provided by wealthy residents in the city. Initially, no tax was levied on these caravans and other itinerant traders by the government but they were expected to present a small gift to the king and senior officials.21

Kano's main market, the Kasuwan Kurmi, had been established by Sarki Rumfa in the 15th century, with most of the market officials remaining in place by Alwali II's time. Kano's primary trade items were its local manufactures, especially its signature textiles that were used both as clothing and as currency. Kano had by the 17th century established itself as one of the major cloth producers in west Africa supported by its vast cotton plantations in the state, its signature indigo-dyed robes, veils, turbans and trousers being traded north to the Tuareg, east to Kanem-Bornu, west to the Niger valley and the Senegambia region and south to Yoruba country. Strips of cloth of uniform size, weave and dye called turkudi served as secondary currencies (complementing gold dust, silver coinage and cowries) and were favored by merchants in the region The second most lucrative trade items were leatherworks such as footwear, armor, bags, book covers, beddings etc. The most important imports were salt from the Sahel (brough by Tuareg and Kanuri traders), Italian paper from Northafrica (brought by Berbers and Arab traders), kola from Asante (modern Ghana) as well as silk cloths and other manufactures. Kano had in the early 18th century been briefly supplanted as the Hausaland’s economic capital by Katsina (a neighboring Hausa city-state to its north) because of the Kano state’s response to the cowrie inflation in the local market, ie: the high taxation used in an attempt to curb it, but selective immunity of influential traders from this taxation saw Kano recover its position under Sarki Yai II (r. 1753-178) and Sarki Zaki (r. 1768-1776) continuing into Alwali' II’s reign.22

Collection of state revenues was governed by both Hausa custom and Maliki-Islam law and were thus derived from the following; inheritance taxes (such as 33% on deceased officials assets and10% of deceased private individuals' property), 20% of war booty, 10% on civil transitions that occurred through its court, 10% on cereal/grain harvests and mining products. The grain was collected by Hakimai and stored in large granaries under their care, it was mainly held as reserve against famine but was also used to supply the royal court since the Sarki was always informed of the amounts of grain collected and locations of the granaries where it was kept after every harvest. Alwali is recorded to have collected stores of sorghum and millet as reserves against war.23

Epilogue: Inflation, taxation, revolution and the fall of Kano

Cowrie inflation imported into Kano

In the early 18th century, a new route for importing cowries into Kano was opened through yoruba country that was coming directly from the Atlantic economy, unlike the relatively small amounts of cowries in Kano arriving from transaharan routes, these Atlantic cowries arrived in sufficient quantities; with more than 25 tonnes of cowries being brought into the neighboring Hausa city-state of Gobir from the Nupe (in Yoruba country) between 1780-1800 AD.24 This increase in cowrie circulation in the Hausalands was part of a wider phenomenon across west Africa as the 18th century that saw vast quantities of cowrie imported from european traders, these cowrie imports rose from an average volume of 90 tonnes annually in the decade between 1700-1710; to 136 tonnes a year in 1711-1720; to 233 tonnes in 1721-1730 (with spikes as high as 323 tonnes in 1722, 306 tonnes in 1749) the average annual imports of cowrie then gradually fell in the 1760s to 61 tonnes but resumed to 136 tonnes a year in the 1780s25, The supply of currency in west Africa during the 18th century was thus exceptionally high both along the coast and in the interior as evidenced by the fact that just one Hausa city (Gobir) could absorb nerly 2% of west africa's annual currency supply, and this doesn’t include the cowries arriving from the transahran routes and the influx of Maria Theresa Thaler coinage in the 1780s. West African states faced a new challenge of inflation to which they responded with what by then considered to be unorthodox taxation policies. (this inflation and taxation is best documented in the “chronicle of Timbuktu” written by a resident scholar; Mawlāy Sulaymān in 1815)

Cash taxation in response to the inflation

These increased volumes of cowrie currency without corresponding increases in production of tradable goods triggered an inflation in Kano beginning with Sarki Sharefa's reign (r. 1703-1731) who tried to curb the cowrie inflation by introducing; monthly taxation paid in cash (ie cowrie) at Kano's Kurmi market (as opposed to the usual annual tax paid mostly in kind); a cash tax on iterant Tuareg and Arab traders (from whom none was previously demanded); a cash tax on family heads in Kano state (in lieu of grain tribute) and a cash tax on transhumant pastoralists such as the Fulani called jangali (replacing the usual livestock tithe).26

Opposition to these taxes must have been bitter as the Kano chronicle says of Sarki Sharefa that "he introduced certain practices in Kano all of which were robbery", despite this, the taxation was mostly continued by successive Sarkis with varying decrees of intensity; with taxes increasing under Sarki Kumbari (r. 1731-1743) and briefly reducing under Sarki Yaji II (r. 1753-1768) but only for iterant traders -thus attracting them back to Kano- while maintaining the taxes for the rest of the population, Yaji II’s taxation policy was continued under Alwali II’s reign.27

Reaction by Kano’s citizens to these taxes

Response to these new taxes was varied; the itinerant Tuareg and Arab traders left for Katsina during Sarki Sharefa's reign but returned when their taxes were removed during Sarki Yaji II's reign, but the heaviest burden of this cash tax fell on the Maguzawa (non-muslim Hausa groups) who paid 3,000 cowries per family head vs 500 cowries for Muslim Hausa family heads, it was especially heavy for the Maguzawa who had peripheral relations with the economy and couldn't procure the shells easily, but these groups had little avenue for protest so their only recourse was to form larger families (thus reducing the number of taxable family heads), as for the response of the Muslim Hausa within the Kano city itself the Kano chronicle mentions that “most of the poorer people in the town fled to the country”.28

The tax was also relatively heavy on transhumant pastoralist groups particularly the non-sedentary Fulani (as opposed to the sedentary Fulani who had were already citizens of the state). During the dry season, these pastoralists crisscross the Sahel and savanna looking for good grazing lands as well as a market for their dairy products; moving back and forth following the monthly shifts of the rainy seasons. These pastoralists presented an administrative challenge for the (sedentary-based) Hausa city-states as the former were ill formed about local state laws and taxes, while most of these pastoralists were Fulani, the state response to them was unlike the resident Fulani who were part of the local scholarly class (ulama) or were sedentary agro-pastoralists that had for long been familiar with state laws and even had administrative positions in the Kano government such as the Sarkin Fulani, Ja’idanawa and Dokaji. The jangali tax on these pastoralists was intended to force them to avoid Kano altogether or to settle permanently and join the resident Fulani community.29 But for this jangali tax to be successful it required a clearer level of communication between the government and these seasonal populations, but these communications had since been constrained by centralization.

Revolution arrives at Kano

As Nasir’s revolution was growing the Torodbe Fulani (who were sedentary Fulani of diverse origin but spoke fulfude and thus assumed Fulani identity) had established themselves as an prominent group among the diverse scholarly class (ulama) of the senegambia region, it was from these (as well as a few other groups such as the Wolof) that Nasir al-Din heavily recruited in his 1673-1674 movement. While Nasir’ movement was ultimately unsuccessful, the Torodbe would reignite their movement in 1776 by overthrowing the Mandinka-led Denanke state of great Fulo and establishing the imamate of Futa Toro.30

Between Nasir's failed movement in 1674 and the 1776 establishment of Futa toro, the Torodbe migrated from the senegambia to the Hausalands, Muhammad Bello (a scholar and later, sultan of Sokoto) attributed this migration to the wars between the Torodbe and the Tukolor (a Fulani group native to the senegambia and related to but distinct from the Torodbe, Wolof and the Serer). In the Hausalands, the Torodbe became part of the local Ulama (alongside the already established Wangara, Kanuri and Hausa scholars) but were largely village-based thus becoming distanced from the the urban-based Ulama and instead associating more with the peasants and pastoralist Fulani, therefore articulating the peasant's grievances better.31 These grievances came at a time when Hausa governments such as Alwali II's were faced with the challenge of inflation, added to this was the increasing centralization of authority under the Sarkis that had been accomplished by the early 18th century at the expense of constrained communication with the lower levels of society.

It was these political and economic conditions that created a situation ripe for a revolution movement, therefore when the Torodbe cleric Uthman Fodio made a call for reform he found ready support. He called for reform, ostensibly against what he claimed were "oppressive" Hausa rulers who "devoured people’s wealth" through taxes (especially the Jangali tax against which he protested vehemently)32, he claimed that they were opulent, and supposedly practiced a hybridized form of Islam. He recruited his followers mainly from the pastoral Fulani and despite initially failing to take the Hausa city of Gobir in 1804, he succeeded in spreading his movement through letters and writings first to the Sarkis and then to the Ulamas of other city-states. Most of the Sarkis ideologically agreed with some of his reforms but were against his movement, Alwali II reportedly wanted to write to Uthman, accepting his reforms but was advised against it by his Ciroma named Dan Mama, the latter instead accepted the movement of Uthman in secret and offered to support him overthrow Alwali II who knew nothing of this treachery. Dan Mama's father had been appointed Ciroma under Yaji II's reign (1753-1768) as regent to secure the latter's son's election to the throne over the sons of his predecssor’s line, while Yaji II was successful in his goal (since his sons; Zaki, Dawuda and Alwali II himself suceded to the throne), it was at the expense of investing unusual powers in the Ciroma as regent (such as substantial fief holdings that allowed him to raise cavalry units and accumulate wealth to influence the council) so when Alwali II named his one week old infant as Ciroma, and officially dismissed Dan Mama (only retaining him as the regent), the latter was deeply estranged and threw his lot to the first invaders to appear at Kano's gates: Uthman's movement. The Dan Mama would later be rewarded by by Uthman's government who retained him in his lofty office after the overthrow of Alwali II.33

Uthman's movement mobilized followers by writing letters to the Ulama who'd then recruit locally and appoint a leader for their local movement then travel to receive a flag from Uthman; symbolically assuming his as their leader (caliph). In Kano, the Ulama sent for a flag although they didn’t appoint a leader, but the group coalesced enough to battle with Alwali II and successfully defeat two skirmishes sent by him at Kwazzazabo in 1806. After negotiations between Alwali II and Uthman fell apart, battle lines were drawn at Kogo, Alwali II's force was routed and armor was captured, Uthman’s followers then took the town of Karaye and continued advancing towards Kano, losing some forces in an engagement with the armies of Alwali II’s tuareg ally named Tambari, but continued to steadily approach the city of Kano itself. Alwali II met them outside its walls, by then, the Dan Mama (and a few other officials such as the Sarkin Fulani) openly dissented and switched to the invading force supporting it with their own forces (although Dan Mama himself remained in Alwali II’s camp). Alwali II then sent appeals to the Bornu empire but they weren't forthcoming because Uthman had organized his followers in Bornu to block any assistance coming from there, something that they succeeded in doing by blocking the Bornu vizier's troops and threatening Bornu itself. Alwali II therefore turned to other Hausa cities; Katsina and Daura who assembled force to join him, Alwali II thus met Uthman's followers for a pitched battle at Danyaya, the latter had combined all his followers to face Alwali II and after a 3-day battle, they defeated Alwali II’s army, and his allies, all of whom went back to their cities. Alwali II would later face his last battle at the fortified town of Burumburum, Uthman's followers besieged it and managed to breach it after several weeks and in the ensuing battle, Alwali II fell; marking the end of one of the world's longest reigning dynasties.

After this battle, Kano was subsumed in Uthman's Sokoto empire along with other Hausa city-states, their deposed dynasties founded powerful splinter states such as Damagaram, Maradi and Abuja. As for the idealized revolutionary government; the Sokoto empire retained many of the "vices" Uthman had charged the Hausa states of perpetuating and expanded some of them, the jangali tax remained, the market taxes remained, the abhorred taxes on the Ulama remained34 and the opulent palaces of Hausa Sarkis were maintained. Just like the Genevan journalist Jacques Mallet du Pan observed about the French revolution; Uthman’s movement eventually "devoured its own children" gradually at first in the succession disputes of the 1860s and then rapidly in the internecine civil wars that raged in the 1890s. In the end, all states formed during the revolution movement both in support and in opposition to it were but players in the rapidly evolving global economic and political order that culminated in their colonization by Britain in 1904 and ended with the independent state of Nigeria in 1960.

Sokoto empire in 1850

Conclusion

Kano under Alwali II was a Hausa city-state per excellence, a virtually independent kingdom free from the imperial overreach of Kanem-Bornu empire (the preeminent west African power of the time), and able to exert its influence as far as Timbuktu, but Kano under Alwali II was only one of many states in a political order that had been prevailing in west Africa since the early second millennium, an order characterized with the conscious acculturation into the dominant West African political and religious order that involved a delicate synthesis of traditional customs and Islam, but one that increasingly favored the latter when articulating and legitimizing power. This complex equilibrium was supported by an elaborate economic system which furnished the state with revenue in tribute rather than in cash, and mobilized armies from territorial fief holders rather than maintaining them permanently.

This entire political and economic system was threatened once new forms of articulating and legitimizing power were propagated, and once the rapidly evolving global economic order washed shiploads of cowrie currency onto the west African littoral and into the interior, as Toby Green observed, powerful fiscal-military states equipped with relatively modern firepower and robust taxation systems such as Dahomey and Asante did not fall to the revolution sweeping west Africa35, (Asante and Dahomey in fact expanded northwards, absorbing Muslim states in their path), while states where such fiscal- military systems were embryonic (like Kano under Alwali II) or nonexistent (like Segu), fell to the revolution movement. Some of the revolution states were themselves inturn absorbed by other reform movements once they failed to implement these fiscal-military systems; such was the fate of the Massina empire which fell to Umar Tal's Tukulor empire whose standing armies were equipped with modern rifles.

Alwali II was therefore a leader faced with a complex interplay of economic and political phenomena most of which was beyond his control, while discourses on west Africa's revolutions has given outsized credit to the cleavages of ethnicity and new sects of Islam, and have gone on to anachronistically extrapolate them into modern conflicts couched within the same theories of ethnicity and religion, few have examined the revolutions in 18th century west Africa from political and economic angle which would offer a far more accurate assessment of circumstances that led to their success.

Far from myopically placing blame on villains and lauding heroes, this observation of Kano under Alwali II presents a balanced portrait of a west African ruler in the midst of a happenstance driven process of revolution, such a nuanced perspective of political paradigms should guide our interpretations of modern African political movements, the entrenched leaders they seek to replace and provide an assessment of the political order that these movements establish once in power.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

for free downloads of books on Huasa history and more on African history , please subscribe to my Patreon account

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick, pg 256-7

The man who would become caliph by S Cory, pg 197

Government in Kano by M. G. Smith, pg 141

M. G. Smith, pgs 48-49

A Reconsideration of Hausa History before the Jihad by Finn Fuglestad pg 326-339

M. G. Smith. pg 116-117

M. G. Smith. pg 145

M. G. Smith. pg120

M. G. Smith, pg 159)

M. G. Smith, pg 161

The history of islam in africa by Nehemia levtzion, pg 97-98

Nehemia levtzion, pg 73)

chapter: “the origins of Jihad in west Africa” in : West Africa During the Age of Revolutions

by Paul Lovejoy

M. G. Smith pg 48, 49

M. G. Smith pg 170-172

M. G. Smith, pg 73-78

M. G. Smith pg66

M. G. Smith, pg 26-27, 34)

M. G. Smith pg69

sub-chapter: “The experience of state power: the example of kano” in: A fistful of shells by Toby Green

M. G. Smith pg 41-42

M. G. Smith pg 61-63

M. G. Smith 51, 53

The shell money of the slave trade by J. S. Hogendorn, pg 104-105

J. S. Hogendorn, pg 58-62

M. G. Smith, pg 55-61

M. G. Smith pg 61-63

M. G. Smith pg 59

M. G. Smith pg 57

Nehemia levtzion pg 77,78

Nehemia levtzion pg83, 85

M. G. Smith pg 55

M. G. Smith pg 188, 171-173)

Islamic Reform and Political Change in Northern Nigeria By Roman Loimeier, pg 12

sub-chapter: “conclusion: reforming the system or reproducing it” in: A fistful of shells by Toby Green

This is the major problem of disunity that Hausa's are facing up to date, may God unite Hausa people to know their value even after my death Amen.

This is just fabricated lies, Since 15th century Kano are in war with neighbouring cities like katsina, Zazzau nd Gobir till around 1780, so they don't have any good relationship at then that one may seek help from other. After jihad paying tax was stopped, and Muslim worship only one God, seek assistance from God alone not from spirit, not like before when they are worshipping two God's.