A complete history of Harar; the city of Saints (1050-1887 AD)

Journal of African cities chapter-4

The city of Harar looms large in the cultural and political history of the northern horn of Africa. Its labyrinthine alleys and cobbled streets flanked by whitewashed stone houses clustered between hundreds of saintly shrines and over 82 mosques, have earned Harar the nickname "city of saints"; and its reputation as the “fourth holiest city of Islam”.

The metropolis of Harar was the capital of one the most powerful empires in north-east Africa, and it later emerged as an independent city-state that issued its own coinage, and was a major center of trade and scholarship, linking the Indian ocean world with the kingdoms of the Ethiopian highlands.

This article outlines the complete chronological history of Harar, including an overview of its political history, trade, architectural monuments, and manuscript tradition.

Map showing the location of Harar city in Ethiopia1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Origin of Harar in the 11th century; the medieval ruins of Harlaa

Traditions about the history of Harar distinguish two periods in the foundation of the city; the first foundation occurred around the 10th century but has strong legendary connotations, attributing the city's establishment to an alliance of seven clans; while the second foundation occurred under the reign of the 'Emir Nÿr (1552-1568) the successor of Imam Ahmad Gran of the Adal sultanate/empire.2

Etymologically, the term “Harla/Harala” is the most likely origin of the name “Harar”, and is also possibly the name of the sultanate of Hārla whose capital Hubät/ Hobat appears in a number of records in the 14th century when its associated with the Ifat kingdom (c. 1286–1435/36) a rival to the Solomonid/Ethiopian empire under Amdä Ṣәyon3. Harla is also an ethnonym that first occurs in written records as “Xarla” in the 13th century Universal Geography of Ibn Saʿīd, as “Harla” in; the 14th century record of the wars of the Ethiopian emperor Amdä Ṣәyon and in the 16th century chronicle of the Adal-Ethiopia wars "Futūh al-Habaša". The term "Harla" later acquired a legendary status among the groups of people who had moved into the region near Harar during the 16th century, it was associated with "giants" who previously occupied the region and were credited with the construction of a range of ruined stone towns near Harar.4

Map showing sites and ruins attributed to the “Harlaa”

Within a radius of 5-13km from Harar are the ruins of several stone built settlements. These ruins include large palatial houses constructed in the form of medieval castles, civic buildings, workshops, mosques, dozens of houses, cemeteries with inscribed stone slabs, coins from the Byzantine empire, Ayyubid Egypt and Song-dynasty china, imported and locally manufactured jewellery, glassware and pottery.5 The establishment of the settlement at Harlaa based on the inscribed stone slabs has been dated to the 11th century lasting until the 15th century, and the majority of the population was local suggesting that Islam was adopted rather than brought in by immigrants.6

Harlaa was a cosmopolitan hub of both Muslim and non-Muslim inhabitants who included merchants and craftspeople from different regions, ethnicities and traditions. These individuals exchanged goods and commodities, as well as knowledge and beliefs and the city was part of an extensive trade network extending from the redsea coast to the Ethiopian highlands. The archeological results from Harar and Harlaa suggest a direct chronological link between the two settlements and affirm the importance of the urban environment as a context for Islamic conversion7

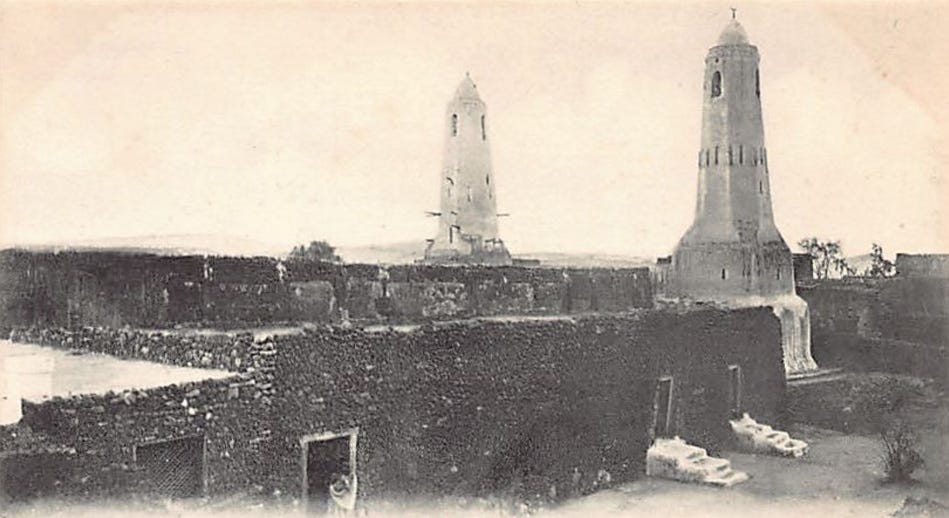

Ruins of buildings at Harar including the castle/citadel below

Coins found at Harar; Byzantine trachy of the Emperor Theodore Komnenos Doukas (1224–1230), Song dynasty Chinese coin, Ayyubid dynasty (egypt) coins.8

The foundation of Harar in the 15th century: Geo-political rivary in the northern Horn of Africa

The northern Horn of Africa in the late 15th/early 16th century

The present city of Harar was established around the 15th-16th century and was closely associated with the emergence of the Adal empire as a major power in the northern Horn of Africa. Harar initially appears as a province under the governorship of Imam Mahfuz, who was a vassal of the Adal emperor Azhar ad-Din (r. 1488-1518).9 Mahfuz's skirmishes on the eastern borders of the Ethiopian empire prompted the latter's retaliation with a battle that ended with a temporary period of peace. By 1519, Harar had become the new capital of the Adal empire during the reign of Azhar's successor Abu Bakr, and was a major base from which Abu Bakr's successor Ahmad Gran launched his conquest of the Ethiopian empire with the help of the Ottomans, until they were ultimately turned back and sought refuge in Harar.10

Ahmad's nephew named Nur Ibn Mujahid became the ruler of Harar in 1551. He is credited with extensive construction work around the city, including building a wall and rampart around the city accessed through five gates that divide the city into five districts (Assum, Argob, Suqutat, Badro and Asmadiri).11 Hoping to repeat the successes of his uncle, Nur advanced into the Ethiopian empire, invading its south-eastern province of Fatagar in 1559 and later defeating the emperor Galawdewos who died in battle. Nur returned to Harar without consolidating his victory in order to fend off the advance of eastern Oromo groups (of the Barentu moeity) that reached Harar in 1567, besieged it and sacked it, before he died in 1568.12

Nur was succeeded by a slave-official named Uthman but the latter had little power over the aristocracy of Harar but succeeded in negotiating a treaty with sections of the Barentu who were accepted into the city's markets on condition of leaving their arms at the Gates. Uthman was deposed by Talha in 1569 who was inturn deposed by Uthman's son Nazir in 1571, who was inturn succeeded by his son Muhammed b. Nâsır in 1572. Muhammed joined another Ottoman alliance against the Ethiopian empire in 1573, they launched their attack between 1577 and 1579 but were defeated and many Harari nobles died in battle along with the Ottoman pasha Radwan. Harar was again besieged by nomadic groups and ceased to be the capital of Adal which retreated to Aussa before it declined into obsolescence, and Harar became its own independent kingdom in 1647 under ʿAlī b. Dawūd.13

Panorama of Harar and its hinterland in 1944, quai branly

The Fallana Gate in the north, Harar, 1885, BNF Paris

The city-state of Harar from the 17th to 19th century; trade, mosques, shrines, and scholarship.

Harar under the Dawud dynasty from 1647-1875 was an independent city-state governed by its own rulers (titled Emir) who also minted coinage inscribed with their names. Harar's caravans reached the regions of southern and central Ethiopia from which they acquired commodities (ivory, salt, rubber) that they added to the local agricultural produce (coffee, sorghum), as well as gold and silver jewellery, and sold to the indian-ocean ports of Zayla, and Berbera. Harar continued to grow into a major center of learning and pilgrimage beginning in the 16th century with the establishment of cults of local saints and their shrines; the composition of a substantial body of Arabic literature; the construction of several mosques; and the growth of the Qadiriyya brotherhood that was instrumental in Islamic proselytization across the region.14

Harar’s rulers begun minting their own coins around the 16th century, when the usage of gold and silver coins called ashrafi and mahallak was introduced, with 22 of the latter being equal to 1 of the former during the 18th century, and several hundred thousand would have been in circulation at a time. Different dies were used by different rulers, and the coins’ sizes, weight, and content of the gold and silver changed depending on the economic circumstances, with the highest quality coins belonging to Abd al Shakur (1783-1794), while the most devalued belonged to Muhammad ibn Ali (1856-1875).15

Harar coinage issued in 1222 AH, 1304 AH (1807, 1887 A.D), University of Illinois

Gold and silver ornaments encrusted with carnelian gemstones and diamonds, made in Harar between the late 19th and early 20th century, quai branly

section of a market in Harar selling textiles, 1885, BNF Paris

A caravan just outside Harar, 1889, BNF Paris

Harar presently has over 88 mosques with 82 found inside the walls, the vast majority having been built before the late 19th century. Every mosque possessed a Waqf property such as a piece of farm land or house for lease given to it by a patron, these endowments served to finance its construction and maintenance as well as associated institutions such as schools. The mosques were built in a similar fashion as other constructions in Harar such as the houses and palaces. Walls were built with limestone and granite bound by mud-mortar and reinforced with timber, they were plastered with white lime-wash, and the building was covered by a flat roof of of juniper rafters and stone, with semi-circular rain spouts to drain rainwater. While there are around 6 old mosques in Harar (aw Abdel, aw Abadir, aw Meshad, Din Agobera, Fehkredin and Jami) that are traditionally dated to the 13th century when the saint Abādir is said to have come to Harar from mecca with his companions, recent archeological excavations next to the mosques found that their construction begun after the late 15th century, with many being substantially remodeled in the 18th and early 19th century, around the time when the rest of the other mosques were built.16

Emir’s residence, Harar, 1885, BNF paris

Jami mosque in the late 19th century before its renovation

Floor plan of the Jami mosque17

Harar rooftops c. 1905

Harar is home to between 103-107 shrines of saints within its walls and more outside its walls, that give the city its alternative name; Madīnat al-Awliyā or “City of Saints”. These saints were local and foreign figures (Harari, Arab, Somali, Oromo), both male and female, who played a significant role in the city's politico-religious history, and their shrines are referred to as āwach suggesting their importance as founding fathers and ancestors of the inhabitants of the city. Knowledge about the saints and their shrines is variable on the basis of such factors as gender, ethnicity, descent, area of residence, the shrine's importance is such that half of all neighborhoods in the city's 5 districts are named after their local shrine, and a number of important religious festivals are celebrated in the shrines.18 These saintly shrines built in honor of figures that were perceived to be intermediaries between God and Man due to the saint's barakah, became important pilgrimage sites that acted as neutral meeting grounds for people of diverse ethnic --and in some cases religious-- origins, seeking blessings and solutions.19 Their basic structure consisted of a domed building about 3-6 meters in height accessed through a low door, inside of this structure is the saint's covered tomb and an open space. The structures are often associated with natural objects such as trees, rocks and pools that are also found among surrounding non-Muslim groups suggesting their pre-Islamic origin and the syncretic nature of Harar's cult of Muslim saints.20

Shrine of Aw Abadir (in 1899, today); Shrine of Aw Aw Abdulkadir Jeylan

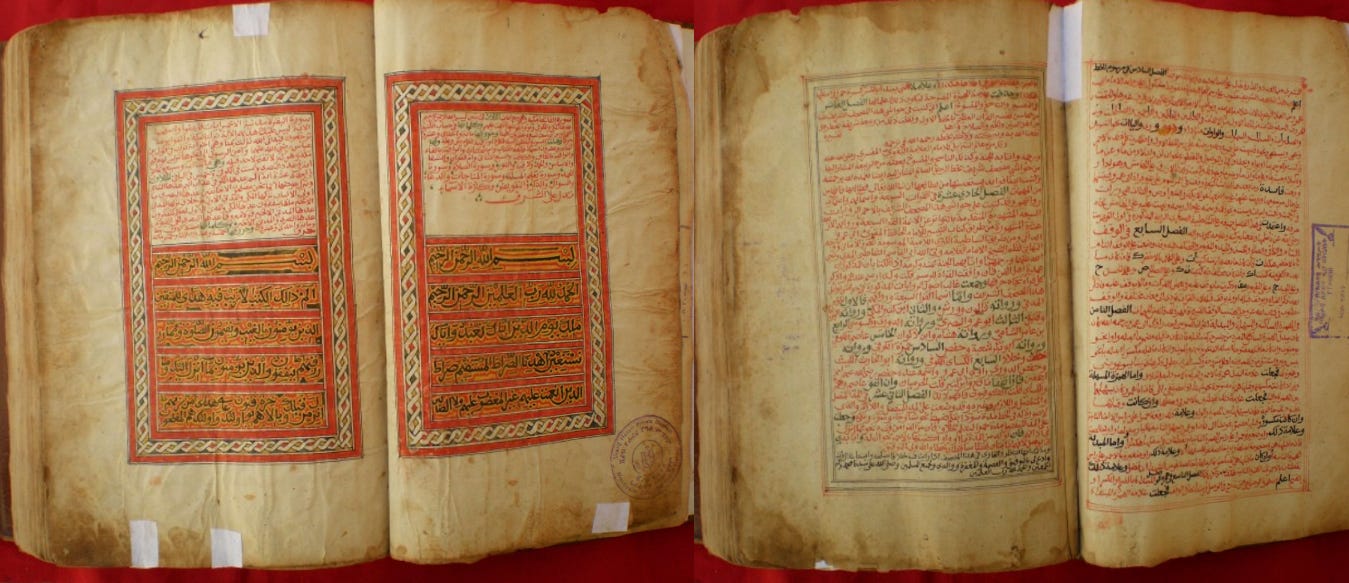

Harar was a major center of scholarship in the northern Horn of Africa, with a significant manuscript tradition that included the composition and copying of documents written in the languages of Arabic and 'Old Harari', these include Qurʾāns and devotional works, didactical and instructional works in theology and law, as well as poetry, grammar, and mysticism (taṣawwuf). Some of the oldest preserved manuscript that has been studied is dated to 1701 and the oldest composed locally is dated to 1724, but many of these were part of a tradition that begun in the 17th century or earlier as private collections in Harar often contain manuscripts pre-dating the 18th century.21 Prominent scholars include Šayḫ Hāšim al-Hararī (c.1711–1765) who was a teacher and a very prominent figure in both the Arabic and the Old Harari literature that composed several religious works of devotional and mystical content. Other scholars include; Hamid b Saddiq al-Harari who lived in Harar in the 18th century and served as a jurist22 ; and Ay Amatullah (1851-1893), a daughter of the qadi of Harar, she became a faqih and teacher of both men and women students.23

Manuscript titled 'Tafsir Kitabul wadih' with astrological diagrams, written in 1687 in Harar, Sherif Harar City Museum24

Composite manuscript with Commentaries; Magical texts; Scientific works; Medical works; Poems; Prayers, written between the 17th and 18th century, Sherif Harar City Museum25

Qurʼan written in 1812, Sherif Harar City Museum26

Talismanic Manuscript written in Harar on April 1796, Addis Ababa museum27

Political history of the Harar city-state from the 18th century until the Ottoman occupation in 1875

The city-state of Harar comprised the walled city which was divided into five districts each forming administrative units, and its immediate hinterland which was also divided into five large territories following the same administrative structure.28 The rulers of the walled city had entered into a symbiotic relationship with the agro-pastoral groups in its hinterland the most prominent of whom was the Afran-Qallu (a confederation of the Barentu subsections named; Oborra, Alla, Nole and Babile) who provided surplus produce (sorghum, coffee), as well as cattle products and ivory for the city's markets in exchange for collecting tolls from merchants and receiving trade goods (textiles and salt), as well as becoming part of Harar's aristocracy and land-owning elite. But relations were not consistently amicable especially because of the succession conflicts that characterize Harar's political history, which often involved alliances with different Afran-Qallu groups by rivaling Harari factions. Thus between the late 18th and early 19th century; the Harar Kings Ahmad ibn Abu Bakr (I755-82) and Ahmad ibn Muhammad (I794-I821) led expeditions into Harar's hinterland.29

Succession crises after the passing of Ahmad preceded the ascent of Abd al-Rahman who relied on a military alliance with the Babile, he managed to rule until 1827 when he was deposed by his brother Abd al-Karim ibn Muhammad after the former's failure to extract tribute from the Alla. Al-Karim's ascent through civil war had devastated Harar's hinterland and enabled him retain the city's firm control over it, that continued into the reign of his successor Abu Bakr (1834-52). But by the mid-19th century, raids on many of Harar's caravans that ventured outside its walls had sapped the city's trade especially during the reign of Ahmad Abu Bakr (1852-6), when the city was forced to pay tribute to the hinterland groups to avoid destruction and armed parties were allowed into its gates contrary to tradition. A military alliance between the Afran-Qallu and Muhammad ibn Ali enabled the later to take over Harar after Abu Bakr's death, ascending to the throne in 1856, and ruling until the city's conquest by Ottoman Egypt in 1875.30

One of Harar’s old city gates, 1934, quai branly

Harar in the late 19th century; from the Ottomans in 1875 to modern Ethiopia in 1887.

The Ottoman-Egyptian forces advanced into Harar in 1875 as part of a wider conquest of North-east Africa following their occupation of Sudan in the 1820s, and their conquest of the Somali coast after taking Zeila and Berbera in the 1870s. The Ottoman commander Rauf Pasha deposed (and later killed) Muhammad ibn Ali in October 1875 after a brief resistance by the forces of the Afran-Qallu.31 The Egyptians would occupy Harar from 1875 to 1885, and during this time, the structure of Harar's administration and society was significantly altered especially the political and economic relationship between the city and its hinterland, as well as the adoption of Islam among the Afran-Qallu.32

The city had an estimated 35,000 inhabitants in 1875, its 3-4m high walls with 24 towers and 5 gates enclosed an area of 0.5 km sq, and its effective authority over the hinterland had shrunk to a radius of about 10-15km outside its walls. It still retained its religious significance its status in long-distance trade and its very productive agricultural output, but didn't have a significant crafts industry. The Egyptian settlers who settled in Harar during its brief occupation (mostly soldiers and their families) came to comprise 25% of its population, pacifying the city and hinterland, and remitting taxes back to Cairo.33 In May 1885, the Ottoman-Egyptians evacuated Harar as part of a wider withdraw from their NorthEast African possesions outside Egypt, and Abdullahi was elected by the town's patricians as their ruler. Abdullahi reigned briefly until 1887 when the city was subsumed into modern Ethiopia.34

Raouf mosque, the ottoman mosque built after 1875, c. 1885 photo, BNF Paris

Palace of ras makonnen in Harar, c. 1905

View of Harar, 1944

The “Ancient Egyptian Race controversy” is most divisive topic in modern Egyptology, in this article, i explore ancient Egypt’s definition of “ethnicity” and their relationship with the kingdoms and people of Nubia;

If you liked this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal/Ko-fi

map prepared by N. Khalaf

Espaces musulmans de la Corne de l'Afrique au Moyen Âge by François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar pg 23)

Material cosmopolitanism: the entrepot of Harlaa as an Islamic gateway to eastern Ethiopia by Timothy Insoll pg 504, The City in the Islamic World pg 625)

First Footsteps in the Archaeology of Harar, Ethiopia by Timothy Insoll pg 209-210, Material cosmopolitanism: the entrepot of Harlaa as an Islamic gateway to eastern Ethiopia by Timothy Insoll pg 488)

New archaeological find in Southeast Ethiopia by Meftuh S. Abubaker , Marine Shell Working at Harlaa, Ethiopia, and the Implications for Red Sea Trade by Timothy Insoll

Material cosmopolitanism: the entrepot of Harlaa as an Islamic gateway to eastern Ethiopia by Timothy Insoll pg 498-501)

Material cosmopolitanism: the entrepot of Harlaa as an Islamic gateway to eastern Ethiopia by Timothy Insoll pg 498-501)

photos and captions from; New archaeological find in Southeast Ethiopia by Meftuh S. Abubaker and Material cosmopolitanism by Timothy Insoll

Ethiopia and red sea by Mordechai Abir pg 69-70, 86

Islam in Ethiopia By J. Spencer Trimingham pg 85)

The Archeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa By Timothy Insoll pg 78)

Islam in Ethiopia By J. Spencer Trimingham pg 91-95)

Islam in Ethiopia By J. Spencer Trimingham pg 96-97)

The City in the Islamic World by Serge Santelli et al pg 626-627)

Harari Coins: A Preliminary Survey by Ahmed Zekaria pg 23-29

The mosques of Harar by Timothy Insoll and Ahmed Zekaria

The mosques of Harar by Timothy Insoll and Ahmed Zekaria pg 89

Baraka without Borders: Integrating Communities in the City of Saints by Camilla C. T. Gibb pg 90-104

The Archeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa By Timothy Insoll pg 80-81)

The City in the Islamic World by Serge Santelli et al pg 632-633)

The Emergence of Multiple-Text Manuscripts by Alessandro Gori et al pg 59-68)

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 3. The Writings of the Muslim Peoples of Northeastern Africa. by J. Hunwick pg 30)

Islam and Gender in Colonial Northeast Africa by Silvia Bruzzi pg 67)

Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa by Stephane Pradines pg 129

Harär Town and Its Neighbours in the Nineteenth Century by RA Caulk pg 371-374)

Harär Town and Its Neighbours in the Nineteenth Century by RA Caulk pg 375-380)

Emirate, Egyptian, Ethiopian pg 38-399

Harär Town and Its Neighbours in the Nineteenth Century by RA Caulk pg 381-384)

'L'occupation égyptienne de Harar (1875-1885)' by Jonathan Miran pg 59-62, 104-105)

Harär Town and Its Neighbours in the Nineteenth Century by RA Caulk pg 385-386)

Another great read, I'd recommend you look into a relatively recent discovery of Hararghe's rock art paintings as being related to the social institutions of the Oromo which has pretty big implications on the general history of the horn of Africa.

The study: Qaallu Institution: A theme in the ancient rock-paintings of Hararqee implications for social semiosis and history of Ethiopia - Dereje Tadesse Birbirso

Also, the etymology of the word "Harla" could be rooted from the word "Allaa" denoting one of the 5 Afran-Qallo clans, I believe it to be a valid theory as it seems to complement this recent discovery

I appreciate this collection as Harari person who already has a little awareness and so to strengthen me in its knowledge and I will teach it certainly to my students and assure it in my quotation in my books Gratitude for you