A complete history of Jenne: 250BC-1893AD

Journal of African cities chapter 6

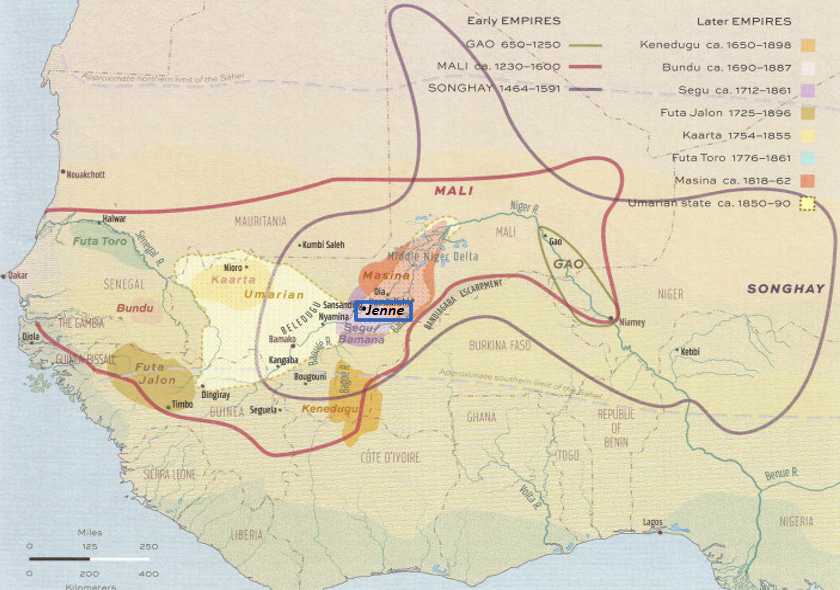

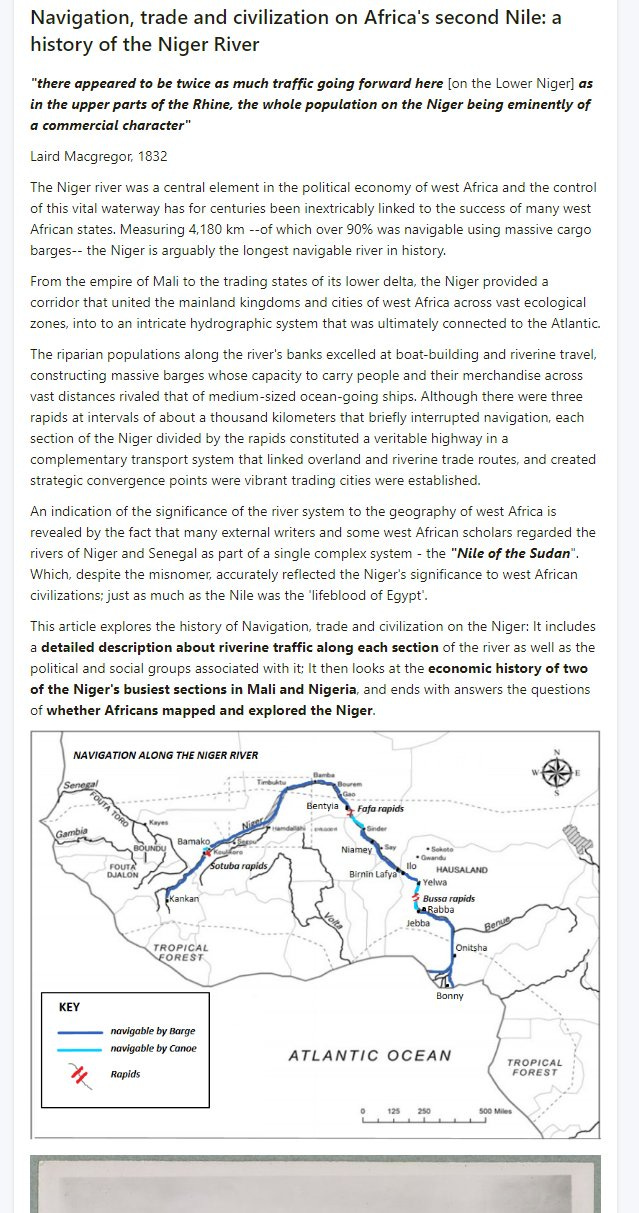

Nested along the banks of the Bani river within the fertile floodplains of central Mali, the city of Jenne has for centuries been at the heart of west Africa's political and cultural landscape.

Enframed within towering earthen walls was a cosmopolitan urban settlement intersected by wide allies that were flanked by terraced mansions whose entrances were graced by majestic baobabs. Inside this city, scholars, merchants and craftsmen mingled in a flourishing community that was subsumed by the expansionist vast empires of west Africa.

Integrated within the vast social landscape, the city of Jenne would have a profound influence on west Africa's cultural history. Jenne’s commercial significance, its craftsmen's architectural styles and its scholars' literary production would leave a remarkable legacy in African history.

This article outlines the complete history of Jenne; including a summary of the city's political history, its scholarly traditions and its architectural styles.

Map of west Africa’s empires showing the location of Jenne1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Origins of Jenne: the urban settlement at jenne-jeno (250BC-1400AD)

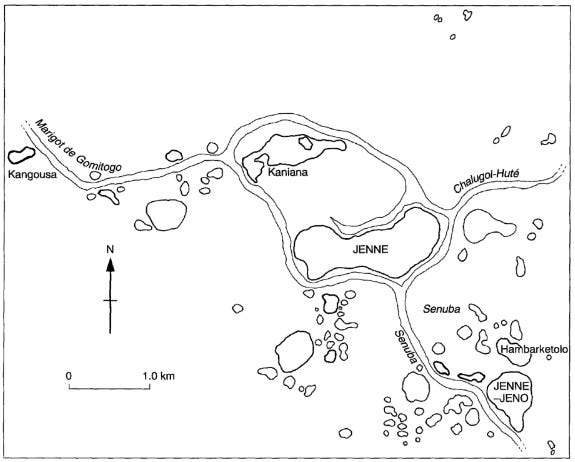

The city of Jenne is built on a large river island in the Bani tributary of the Niger river. The original settlement of Jenne was established at the neolithic site of jenne jeno about 2-3km away, which was occupied from the 3rd century BC to the 15th century AD. Jenne-jeno has revealed the site of a complex society that developed into a considerable regional center, and is one of west Africa’s oldest urban settlements. Surrounded by over 69 satellite towns, the population of the whole exceeded 42,000 in the mid-1st millennium.2

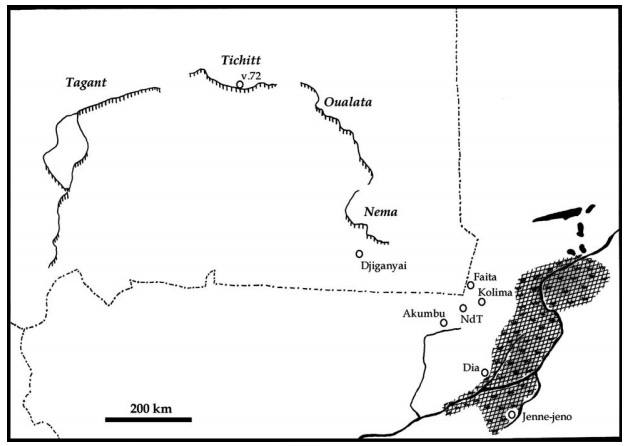

The settlement at Jenne-jeno, and its urban cluster was part of a broader Neolithic tradition that arose in the region of Mema near Mali’s border with Mauritania, which included the ancient settlement of Dia and several small nucleated settlements of related dates in the 1st millennium BC. The Mema tradition was itself linked to the ancient Neolithic sites of Dhar Tichitt in southern Mauritania where arose a vast number of proto-urban sites during the 3rd millennium BC.3

By 800 Jenne-jeno had developed into as a full and heterogeneous agglomeration inhabited by a population of various specialists, with a surrounding wall 2 kilometers in circumference surrounded by a sprawling urban cluster of satellite settlements.4 The present settlement at Jenne was itself established during the last phase of jenne-jeno's occupation around the 12th-13th century, and its oldest settlement has recently been dated to between 1297–1409.5

Reclining figure. ca. 12th–14th century, Jenne-jeno, Musée National du Mali

Jenne-jeno urban cluster, map by R. McIntosh

Map of Jenne-Jeno in relation to the Neolithic sites of Dia and Dhar Tichitt, map by K.C. MacDonald

The history of Jenne under the empires of Mali and Songhai (13th-16th century)

From the 9th-13th century, the hinterland of Jenne fell under the political control of the empires of Ghana and Mali, the latter of which was the first to exercise any real control over the city. Jenne's status under Mali was rather ambiguous. Its immediate hinterland which included the provinces of; Bindugu (along the Bani river between Jenne and Segu); as well as Kala and Sibiridugu (both between the Bani and Niger rivers) were under Malian control by the 13th century. A 14th century account about the Mali emperor Mansa Musa and the 17th century Timbuktu chronicle; tarikh al fattash, both mention that the Mali empire conquered hundreds to cities and towns, “each with its surrounding district with villages and estates”. With Jenne being one of the cities under Mali.6

However, the city may have maintained a significant degree of autonomy throughout the entire period of Mali empire. According to the 17th century chronicle; Tarikh al-Sudan "At the height of their power the Malians sought to subject the people of Jenne, but the latter refused to submit. The Malians made numerous expeditions against them, and many terrible, hard-fought encounters took place-a total of some ninety-nine, in each of which the people of Jenne were victorious." While embellished, this story indicates that Jenne didn't willingly submit to Mali's rule if it ever did.7

The city first appears in external accounts in a description of west Africa by the Genoese traveler Antonio Malfante in 1447 while he was in the southern Sahara region. He mentions the cities of the middle Niger basin then under the (brief) control of the Tuaregs, among which was Jenne (“Geni”). But by the time of the Portuguese account of Alvise Cadamosto who was on the west african coast by 1456, Jenne's ruler was reportedly at war with Sulaymān Dāma, the first Songhai ruler.8

Sunni Ali, the successor of Sulaymān, besieged Jenne in between the years 1470-1473 using a flotilla of 400 boats to surround it with his armies. Daily pitched battles ensued for the next 6 months until the city eventually capitulated, allowing Sunni Ali to establish his residence east of the Great Mosque. This siege must have represented a significant political event, since the Tarik al-sudan noted that "with the exception of Sunni "Ali, no ruler had ever defeated the people of Jenne since the town was founded". Jenne's independence ended with this conquest as successive empires vied for its control. Fatefully, this same conquer of Jenne is reported to have died during another siege of Jenne around 1487-8 and his death would initiate a series of events that led to the coup of Askiya Muḥammad.9

The city would then remain under the Songhai administration through the dual administrative offices of the Jenne-koi (traditional ruler) and Jenne-mondio (governor). The Jenne-koi retained some form of symbolic importance and was reportedly exempt from the practice of pouring sand on the head when approaching the Askiya, as a sign of submission, but even this symbolic autonomy could only go so far, since the princes of Jenne-koi were sent to Gao to be tutored by the Songhai rulers.10 However, Jenne's neighboring provinces of Kala and Bindugu remained independent, wedged between the expansionist Songhay and the declining Mali empire.11

Jenne became more prosperous during the Songhai era. According to the tarikh al-sudan, most of jenne's wealth was derived from its connection to the 'gold mine' of Begho, and it was the gold dust from the latter that Jenne exported through Timbuktu to the Mediterranean12. Leo Africanus’ account written in 1550, mentions that the city's merchants made “considerable profit from the trade in cotton cloth which they carry on with the Barbary merchants”. its residents "are very well dressed. They wear a large swathe of cotton, black or blue, with which they cover even the head, though the priests and doctors wear a white one" and use “bald gold coins” as currency.13

Writing in 1506-1508 based on secondary accounts, Duarte Pereira describes "the city of Jany, inhabited by negroes and surrounded by a stone wall, where there is great wealth of gold; tin and copper are greatly prized there, likewise red and blue cloths and salt, all except the cloth being sold by weight.. The commerce of this land is very great; every year a million gold ducats go from this country to Tunis, Tripoli of Soria [Syria] and Tripoli of Barbary and to the kingdom of Boje [Bougie] and Fez and other parts"14

Aerial view of Jenne, and street scene from 1905/6

The scholars of Jenne.

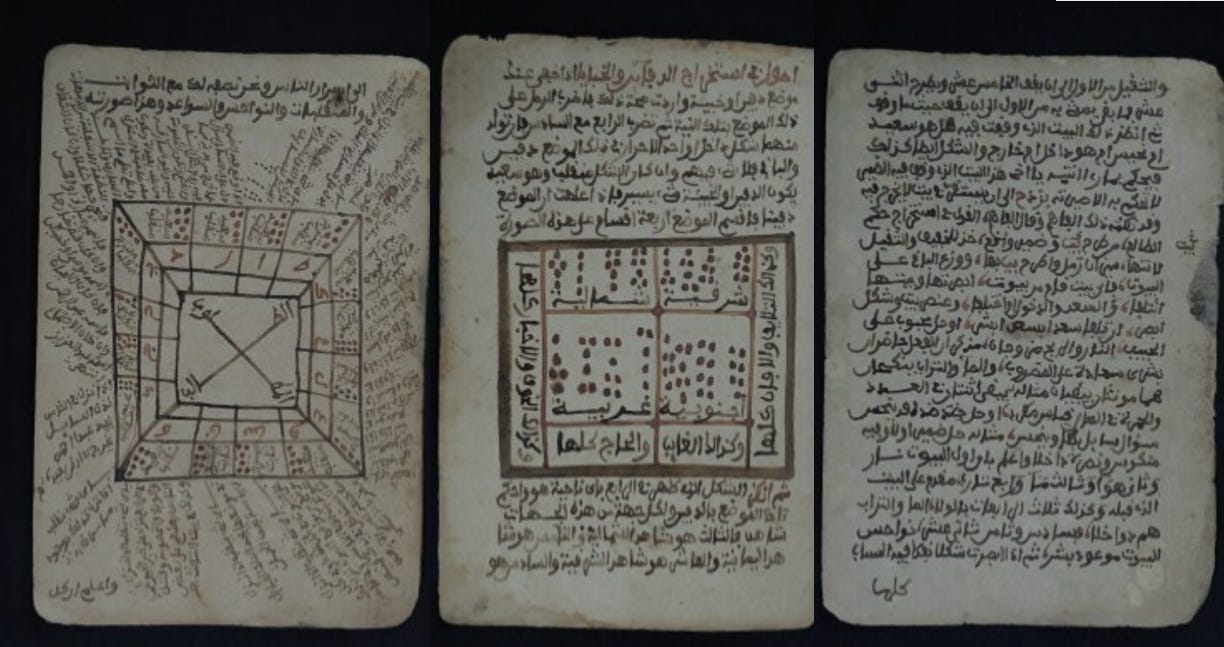

Djenne was home to one of the earliest scholarly communities in west Africa. According to the tarikh-al sudan, Jenne's king Kunburu (ca. 1250) assembled 4,200 scholars under his domain, made three grants regarding the city's status as a place for refugee, scholarship and trade, and pulled down his palace to build the now-famous congressional mosque.15 The city was within the nucleus of the Wangara diaspora prior to their dispersion which spread their Suwarian philosophy and building style across parts of west Africa.

The Wangara/Dyula were an important class of Soninke-speaking merchant-scholars associated with the ancient urban settlements of the middle Niger region (eg Dia and Kabara), that carried out gold trade with north Africa and established scholarly communities across vast swathes of west Africa from the Senegambia to the Hausalands and the Volta basin. Most of the scholars of Jenne were derived from this group as shown by their nisbas; "al-Wangari", "Diakhate", "al-Kabari", and their soninke/Mande clan names etc. The Wangara scholars were also important in the northern scholarly center of Timbuktu as well.16

Among the prominent scholars in Jenne during the Songhai era was al-faqīh Muḥammad Sānū al-Wangarī who was originally born in the town of Bitu (Begho in today's northern Ghana). Al-Wangarī’s life spanned the period before Sunni ‘Alī’s takeover of Jenne to that of Askiya Muḥammad, who appointed him qāḍī of Jenne after the recommendation of Maḥmūd Aqīt of Timbuktu's Sankore mosque.17His appointment in the novel office of qāḍī at Jenne represented a maturation of Islamic scholarship under state patronage and his burial site in the congregational mosque’s courtyard became a site of veneration. He would be succeeded in the office of qadi at Jenne by another Wangara scholar named al-Abbas Kibi, who died in 1552 and was buried next to the Jenne mosque.18

Another leading scholar of Jenne was Maḥmūd Baghayughu, who had a rather adversarial relationship with the Songhai emperor Askiya Isḥāq Bēr. When the Askiya requested that the residents of Jenne name the person who had been oppressing them so he may be punished, Baghayughu said it was the Askiya himself and his overreaching laws —in a bold reproach of his ruler. But shortly after the passing of al-Abbas Kibi (the previous qadi of Jenne), the Askiya coolly repaid Baghayughu's insolence by appointing him as qadi, the overwhelming irony of his unfortunately compromising position drove Baghayughu to his deathbed.19

Jenne’s scholarly tradition continued long after Songhai’s collapse, as the city became a cosmopolitan center of education. Jenne’s learning system was personalized as in most of west Africa, with day-to-day teaching occurring scholar's houses using their own private libraries20, while the mosques served as the locus for teaching classes on an adhoc basis. However, the theocratic rulers of Masina would establish a institutionalized public school system in the early 19th century.21

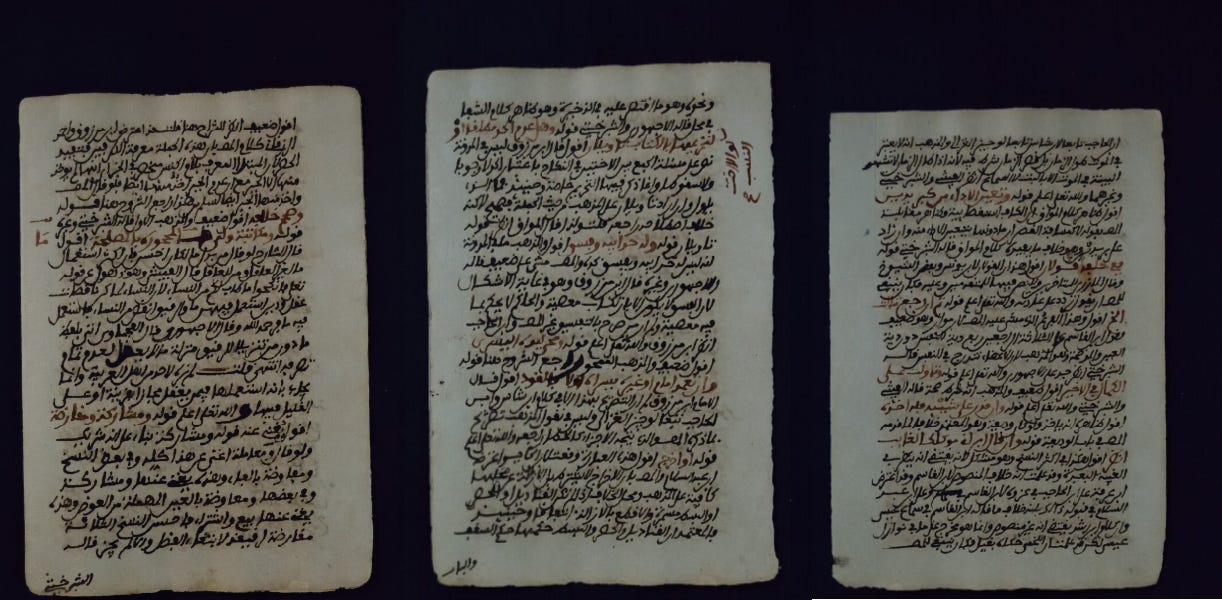

A recent digitization project catalogued about half of the 4,000 manuscripts they found dating back to 1394. but , these constituted only a small fraction of the total number of manuscripts. Many were composed and copied in Jenne by local scholars in various languages including Arabic, Songhai, Bozo, Fulfulde and Bamabara, These manuscripts include copies of west African classics such as the the tarikh al-sudan, but also various works on theology, poetry, history and astronomy.22

Kitāb jāmi‘ al-aḥkām (book of Jamia Al-Ahkam), a work on astronomy and astrology written by Sidiki son of Ibrahim Torofo, ca. 1723-1844, Sekou Toure Family collection.23

Commentary on the "Mukhtasar of Khalil", written by a Jenne scholar in 1723, Sekou Toure Family collection.24

The Old mosque of Jenne more than two decades before its reconstruction, ca. 1895 by A. Lainé, quai branly

Jenne through the Moroccan era and the Timbuktu Pashalik (1591-1618-1767)

There was a general state of insecurity after the collapse of Songhai to the Saadian army in March 1591 and Jenne was caught in the maelstrom. The tarikh al-sudan mentions that the "the land of Jenne was most brutally ravaged, north, south, east, and west, by the Bambara". Jenne's governor sent his oath of allegiance to the Saadian representative (Pasha) in Timbuktu in December 1591. The Timbuktu pasha then sent 17 musketeers (Arma) to install a new Jenne-koi after the previous one had passed away. After putting down a brief rebellion in Jenne led by a former Songhai officer, a garrison of 40 musketeers under the authority of Ali al-Ajam as the first Arma governor of Jenne, alongside the two pre-existing offices.25

Saadian control of Jenne remained weak for most of the time, and the last Pasha was appointed in 1618, after which the rump state based at Timbuktu was largely independent of direct Moroccan control26. Jenne's immediate hinterland remained largely independent, especially the town of Kala which had several chiefs including Sha Makay, who had briefly submitted to the Arma's authority but later renounced his submission almost immediately after assessing their strength and invaded Jenne. The Arma governor of Jenne sent their forces to attack Kala but were defeated and Makay continued launching attacks against Jenne with his forces, among whom were 'non-Muslim' soldiers. (most likely Bambara).27

Jenne also remained a target of the Mali's rulers. In a major attempt at retaking lost territory, the ruler of Mali; Mahmud invaded Jenne in 1599 with a coalition that included the ruler of Masina; Hammad Amina. But Mali's forces were driven back by a coalition of forces led by the Arma and the Jenne-koi as well as a ruler of Kala, the last of whom spared the Mali ruler’s life. Shortly after this battle, Hammad Amina of Masina would later raise an army that included Bambara forces and decisively defeat the Arma and their Jenne allies at the battle of Tiya in the same year.28

Describing contemporary circumstances in the 1650s, the tarikh al-sudan writes that "The Sultan of Jenne has twelve army commanders in the west, in the land of Sana. Their task is to be on the alert for expeditions sent by the Malli-koi (ruler of Mali), and to engage his army in such cases, without first seeking the sultan's authority."29 Besides the continued threat from Mali, Jenne itself rebelled several times between 1604 and 1617, often with the support of the deposed Askiyas, who were trying to re-take the former Songhai territories from their new base at Dendi (along the Benin/Niger border).30

By 1632, the local Arma garrison was itself rebelling against their overlords in Timbuktu and they were soon joined by the Jenne elite in several successive rebellions in 1643 and 1653 before each Arma garrison (at Jenne and Gao) became effectively independent . More rebellions by the Arma of Jenne against the Pashas at Timbuktu were recorded in 1713, 1732 and 1748, during which time, Jenne was gradually falling under the political sphere of the growing Bambara empire of Segu and the Masina kingdom.31

The Bambara in the regions of Kala and Bindugu had always been a significant military threat in Djenne's hinterland during the Songhai era when they had remained independent of the Askiyas. During his routine visits to Jenne in the year 1559, the Askiya Dawud chastised his Jenne-mondio al-Amin for not campaigning against the Bambara forces that had repeatedly invaded the city.32 After Songhai's collapse, they always formed part of the forces of the independent rulers in Jenne's hinterland the chiefs at Kala who launched attacks against the Arma garrisons in the city. It's within the regions of Kala and Bindugu that the nucleus of the Segu empire developed.33

The kingdom of Masina also featured in Jenne's political history during the Songhai era and in the succeeding Pashalik period. Armies from the Masina ruler Fondoko Bubu Maryam reportedly attacked the Askiya’s royal barge in 1582, just as it was leaving Jenne with a consignment destined for Gao, and this attack invited a devastating retaliation from Songhai's armies. In the period following Songhai’s collapse, the rulers of Masina and Segu would in 1739 form a coalition that defeated a planned invasion of Jenne by the king of Kong.34

While Jenne remained under the nominal suzerainty of the Timbuktu Pashalik until around 176735, it formally came under the rapidly expanding empire of Segu during the reign of N'golo Diara (1766-1795). The latter’s reign coincided with the decline of the Pashalik after a series of invasions by the Tuareg forces between the 1730s to 1770s.36

By the time of Diara’s successor king Mansong (d. 1808), Jenne and Timbuktu were both under the control of the Segu empire. Describing this empire’s rapid expansion in 1796 the explorer Mungo Park observed that Jenne "was nominally a part of the king of Bambara's dominions" with a governor appointed by Mansong. The kingdom of Masina also paid "an annual tribute to the king of Bambara, for the lands which they occupy". And the same source in 1800 writes that; "The king of Bambara proceeded from Sego to Timbuktu with a numerous army, and took the government entirely into his own hands". 37

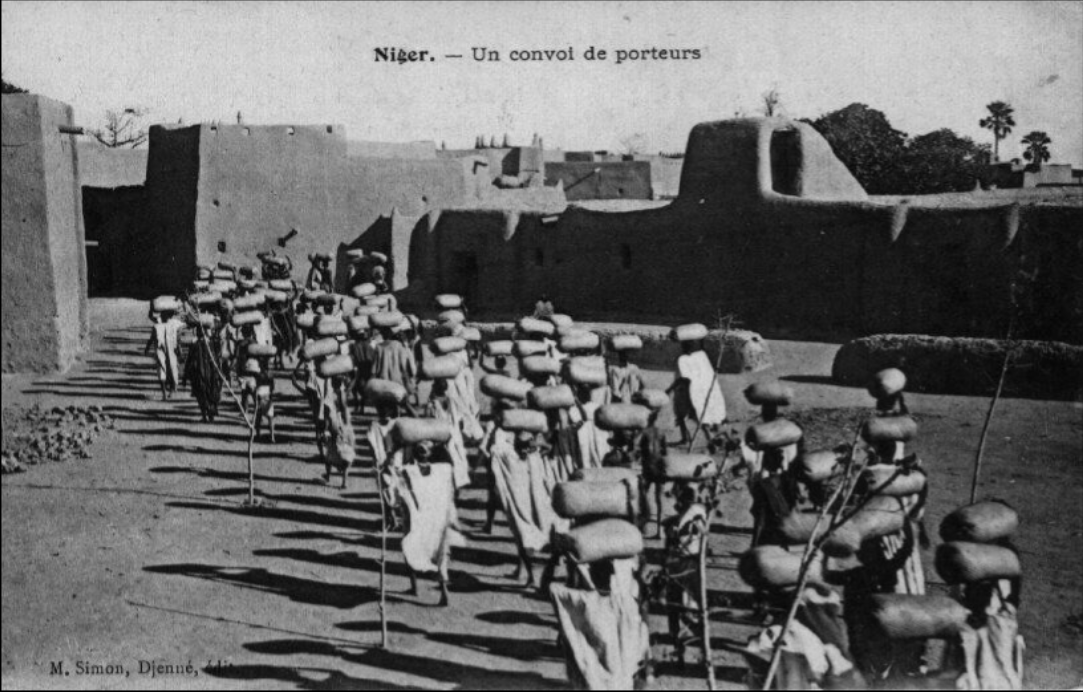

Convoy of porters, Djenne, early 20th century, National Museum of Ethnology Leiden

Jenne through the empires of Segu (1767-1821), Masina (1821-1861) and Tukulor (1861-1893)

Like its previous conquerors, Segu's control over Jenne was never completely firm38. The city was sacked and occupied by the southern kingdom of Yatenga during the 1790s, and their forces only left after Segu's ruler, King Mansong, had paid a fine for having led an earlier attack on Yatenga.39

The city also exerted a significant influence on the court of Segu. The scholars of Jenne reportedly took N'golo Diara in as one of their students, and although he'd maintain his traditional beliefs once installed as king, traders and clerics from Jenne would acquire a special position in the Segu empire. They were often called to intervene as arbiters in political matters and their trading interests along the Niger river were protected by the State.40

The reciprocal relationship between the Jenne elite, the rulers of Segu, and the (subordinate) rulers of Masina, created an unfavorable social and political condition for the Masinanke clerical groups within Masina. By the late 1810s the rising discontent around this unfavorable situation led a large number of followers to rally around a scholar named Ahmadu Lobbo. These forces of Ahmad Lobbo would later invade Jenne after two successful sieges of the city in 1819 and 1821, and Lobbo would occupy it by 1830, after the rulers of Segu had retreated to their capital.41

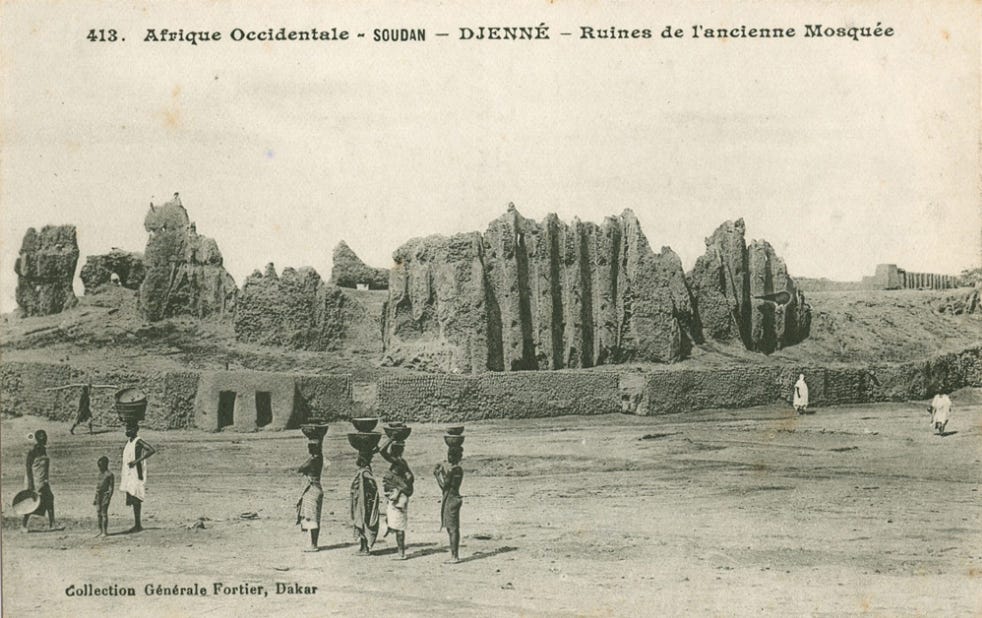

Prior to his conquest of Jenne, Lobbo had composed a treatise titled Kitab al-Idirar that admonished the scholars of Jenne for failing to act as good spiritual guides for the local community. In this text which constituted a political dialectic of legitimization and delegitimization, he directed his criticism against many of the city's institutions as well as the organization of the old mosque. Having earlier clashed with Jenne's elites on numerous occasions at the mosque for occupying seats reserved for the traditional rulers, his criticism was levied against these elites, against the burying of scholars near the mosque, against mosque's columns and against the mosque's height. Lobbo would then allow the old mosque to be destroyed by rain once in power, and it wouldn't be restored until 1907.42

Like most of their predecessors, Masina's control over Jenne wasn't firm, neither was its control over the southern frontier where the Futanke leader Umar Tal emerged, nor over the northern frontier where the Kunta group remained a threat. Umar Tal founded his Tukulor empire in the 1840s along the same pretexts as Ahmad Lobbo, and eventually opposed the alliance between preexisting elites of Segu, and the now established Masina rulers who claimed to be theocratic governors.43A series of wars were fought between the three forces but the Tukulor armies under Umar Tal often emerged victorious, from the conquest of Segu in 1860-1 which became Umar Tal's new capital, followed by the surrender of Jenne and the conquest of Hamdullahi in 1862.44

The fluid political landscape and warfare had further reduced the fortunes of Jenne in the 19th century, as its merchants moved to the emerging cities of Nyamina and Sinsani. But the city nevertheless retained some commercial significance by the time of Rene Caillie’s visit in 1829, who described it as "full of bustle and animation ; every day numerous caravans of merchants are arriving and departing with all kinds of useful productions", its fixed population of just under 10,000 resided in large two-story houses.45

Ruins of the old Mosque, photo by Edmond in 1905/6 about a year before its reconstruction.

The Palace of Amadu Tal in Segou, late 19th century illustration after it was taken by the French

The architecture of Jenne

The architectural tradition of Jenne begun at Jenne-jeno where the signature cylindrical mud bricks first appear in the 8th century, followed not long after by rectilinear buildings with an upper story by the 11th century.46 Given the need for constant repairs and reconstructions, the oldest multi-story structures in Jenne are difficult to determine, but recent archeological excavations in the old town have dated one to the late 18th century.47

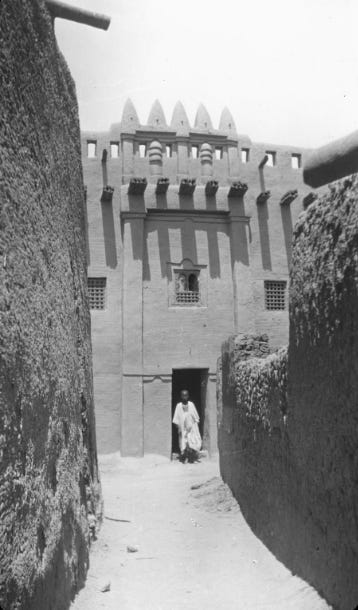

The architectural style of Jenne is characterized by tall, multistory, terraced buildings, with massive pilasters flanking portals that rise vertically along the height of the façade. The tops of the buildings feature modeled earthen cones, which add to the overall monumentality, the building itself reflecting the owner's status and their ability to hire specialist masons.48

The largest buildings in Jenne were constructed by a specialist guild of masons which is still renowned throughout west Africa. These masons are hired widely for their skill in building mosques and palatial residences, with the occupation itself reportedly dating back to the eras of imperial Mali and Songhai. The Askiyas are said to have employed 500 masons from Jenne in the construction of their provincial capital at Tendirma, and the rulers of Segu employed masons from Jenne to construct their palaces (such as the one shown in the photo above).49

While the building’s construction plans are determined by the its functions, the exterior designs of the buildings often carry a more symbolic purpose. The basic design of traditional façade and portal of Jenne's houses and mosques consists of large buttresses (sarafa) on which were placed a component surmounted by conical pinnacles decorated with projecting beams (toron). The whole was modeled after the traditional 'ancestral shrines' and their phallic pillars seen among the Bozo. Jenne’s two main exterior designs; Façade Toucouleur (with a sheltered portal called gum hu) and Façade Marocaine (with an open portal) are based on recent traditions rather than on stylistic introductions of the Tukolor or Arma era, especially considering that the Façade Toucouleur is infact the older of the two; being popular until the 1910s.50

Houses with Façade Toucouleur, ca. 1905/6, Edmond Fortier and Quai branly. The second house is the ‘Maiga House’ the 19th cent. home of the chief of the Songhay quarter of the city during the reign of Amadu Lobbo.

House with Façade Marocaine in 1909, BNF Paris. This type was rare before the 20th century but its the common type today.

Street scene from 1905/6 showing Jenne houses with other façade types.

The mosque of Jenne is the most recognizable architectural monument built by the city’s masons guild. After a century of destruction, it was rebuilt by the masons in 1907 under the direction of their chief, Ismaila Traoré, and its architectural features reproduce many of those found on Jenné’s extant multi-story houses from the 18th-19th century51. Its foreboding walls are buttressed by rhythmically spaced sarafar and pierced by hundreds of protruding torons, with three towers along the qibla wall containing a deep mihrāb niche.52 The emphasis on the height of the mihrab, the front of which used to contain the mausoleums of prominent scholars/saints, exemplifies Jenne's architectural and cultural syncretism and may explain why Jenne-style mosques in west Africa pay special attention to the mihrab rather than the minaret.53

East elevation and floor plan of the Jenné Mosque by Pierre Maas and Geert Mommersteeg

The main construction material was the Djenné-Ferey bricks and palm wood. The bricks were made from a mixture of mud, rice husks, and powders from the fruit of the Boabab and Néré trees, these were mixed, moulded and dried in the sun.54 The specialist knowledge of construction was passed on through apprenticeship, The houses' vestibule, inner courtyard, rooms, kitchen, toilet shaft, inner staircase, terrace and ceilings of both floors are built according to the skill of each mason. The roof structure is built on the ground and then lifted and placed on the house, its open space is filled perpendicular with timber beams in a convex structure that drains rainwater into clay pipes on the sides.55

Jenne's masons also preserve aspects of the city's pre-Islamic past, their profession being rooted in traditional cultural practices. Among their customs are syncretic rites which performed after construction inorder to protect the houses, which utilize both amulets and grains that are buried in the foundations.56craftspeople like masons invoke powerful trade “secrets” (sirri) that blend Qur’anic knowledge (bey-koray) with traditional knowledge (bey-bibi), and many people don protective devices beneath clothing and wear blessed korbo rings on their fingers to defend against malevolent djinn.57

The decline of Jenne

The Tukulor state's control over Jenne was as weak as its control over most of its provinces, especially following the death of Umar Tal and the resurgence of the Masinanke and Kunta attacks and their unsuccessful a 6-month siege of jenne in 1866.58 Jenne fell under the one half of the Tukulor empire led by Amadu Tal at his capital Segu, while the other half led by Tijani Tal was based in Bandiagara. During this time, the office of the Jenne ruler was occupied by Ismaïl Maïga (d. 1888) whose family was previously chief of the Songhai quarter during the Masina era, he would be succeeded by his brother Hasey Ahmadou who would remain in power during the transition from the Tukulor to the French.59

In 1893, Jenne fell to the French forces of Archinard after three days of bombardment and vicious street fighting.60Under their aegis, the bulk of Djenne's trade was transferred to the rising urban commune of Mopti, and Djenné’s prominence slowly waned, transforming a once-thriving center into a marginal town, albeit one of important historical significance.

Like many of the old cities of west Africa, Jenne owed much of its success to the Niger river which provided a navigable waterway where massive cargo barges moved people and their merchandise from as far as Guniea to the southern coast of Nigeria.

read about the history of the world’s longest navigable river

If like this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

Taken from Alisa LaGamma "Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara

Exchange and Urban Trajectories. Middle Niger and Middle Senegal by Susan Keech McIntosh pg 527-536, Africa's Urban Past By R. J. A R. Rathbone pg 19-26

Betwixt Tichitt and the IND: the pottery of the Faïta Facies, Tichitt Tradition by K.C. MacDonald

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa by Michael A. Gomez pg 17-18)

Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond by D. Mattingly pg 533, Africa's Urban Past By R. J. A R. Rathbone pg 26.

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa by Michael A. Gomez pg 127, 137)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 16)

African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa by Michael A. Gomez pg 151-153).

African dominion by Michael A. Gomez pg 187-188, 205, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 20)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg xli,xlviii. African dominion by Michael A. Gomez pg 265)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 171)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 18-19

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 277-278)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 17, n2)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 18-19, The History of the Great Mosques of Djenné by Jean-Louis Bourgeois pg 54

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg xxviii-xxix)

African dominion by Michael A. Gomez pg 213-214, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 24-26)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 26)

African dominion by Michael A. Gomez pg 273-275)

In the shadow of Timbuktu: the manuscripts of Djenné by Sophie Sarin pg 176

Travels through Central Africa to Timbuctoo by René Caillié pg 461

From Dust to Digital: Ten Years of the Endangered Archives Programme, 2015, pg 173-188

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 161, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 193, 207-214)

Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century by Unesco pg 157

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 231-232)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 234-236)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 20)

Muslim traders, Songhai warriors, and the Arma pg 76-77, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 250-256)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 162, sultan caliph pg 8-9.)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 149)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 171-174)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 158, The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 184)

Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century by Unesco pg 158

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 128)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 177-178)

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves by Richard L. Roberts pg 42

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 186)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 129)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 9-11, 161, 140, The Bandiagara emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 42)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 137-141)

The Bandiagara emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 37-39, 47-49,)

Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves by Richard L. Roberts pg 83

Travels through Central Africa to Timbuctoo by René Caillié pg 459, 454.

Excavations at Jenné-Jeno, Hambarketolo, and Kaniana by S.Mcintosh pg 65)

Ancient Middle Niger by Roderick J. McIntosh pg 158, Tobacco pipes from excavations at the Museum site by S. Mcintosh pg 178)

Butabu: Adobe Architecture of West Africa By James Morris, Suzanne Preston Blier 196, The Masons of Djenné by Trevor Hugh James Marchand pg 16)

Historic mosques in Sub saharan by Stéphane Pradines pg 101, Butabu: Adobe Architecture of West Africa By James Morris, Suzanne Preston Blier pg 194)

Historic mosques in Sub saharan by Stéphane Pradines pg 101, The Masons of Djenné by Trevor Hugh James Marchand pg 88)

The History of the Great Mosques of Djenné by Jean-Louis Bourgeois

Religious architecture: anthropological perspectives by Oskar Verkaaik pg 124-127

Historic mosques in Sub saharan by Stéphane Pradines pg 102

The Politics of heritage management in Mali by CL Joy pg 59-60

Negotiating Licence and Limits by THJ Marchand pg 74-75, Masons of djenne by THJ Marchand pg 219)

Masons of djenne by THJ Marchand pg 8, 90-91, 152-153, 168, 171, 288-289, Negotiating Licence and Limits by THJ Marchand pg 78-79)

Religious architecture: anthropological perspectives by Oskar Verkaaik pg 121

The Bandiagara emirate by Joseph M. Bradshaw pg 77,

Djenné: d'hier à demain by J. Brunet-Jailly pg 9-41

Conflicts of Colonialism By Richard L. Roberts pg 110)