A complete history of Madagascar and the island kingdom of Merina.

State and society on Africa's largest island.

Lying about 400km off the coast of east Africa, the island of Madagascar has a remarkable history of human settlement and state formation. A few centuries after the beginning of the common era, a syncretized Afro-Asian society emerged on Madagascar, populating the island with plants and animals from both east Africa and south-east Asia, and creating its first centralized states.

From a cluster of small chiefdoms centered on hilltop fortresses, the powerful kingdom of Merina emerged at the end of the 18th century after developing and strengthening its social and political institutions. The Merina state succeeded in establishing its hegemony over the neighboring states, creating a vast empire which united most of the island.

This article outlines the history of Madagascar and the Merina kingdom, from the island's earliest settlement to the fall of the Merina kingdom in the late 19th century.

the nineteenth century Merina empire, map by G. Campbell.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and to keep this blog free for all:

Background on the human settlement of Madagascar.

The island of Madagascar is likely to have been first settled intermittently by groups of foragers from the African mainland who reached the northern coast during the 2nd to 1st millennium BC.1 Permanent settlement on Madagascar first appears in archeological record during the second half of the 1st millennium, and was associated with the simultaneous expansion of the Bantu-speaking groups from the mainland east Africa and its offshore islands, as well as the arrival of Austonesian-speaking groups from south-east Asia.2

Linguistic evidence suggests that nearly all domesticates on Madagascar were primarily introduced from the African mainland, while crops came from both Africa and south-east Asia.3 There were significant exchanges between the northern coastal settlements of Madagascar and the Comoros archipelago, with chlorite schist vessels and rice from the former being exchanged for imported ceramics and glass-beads from the latter. These exchanges were associated with the expansion of the Swahili world along the east African coast and the Comoros islands, of which northern Madagascar was included, especially the city-state of Mahilaka in the 9th-16th century. Other significant towns emerged all along the island's coast at Vohemar, Talaky, Ambodisiny, and in the Anosy region, although these were not as engaged in maritime trade as Mahilaka.4

the peopling of Madagascar, map by P Beaujard

Ruins of the city wall of Mahilaka in north-western Madagascar, the Swahili town had a population of over 10,000 at its height in the early 2nd millennium

It was during this early period of permanent settlement that the Malagasy culture emerged with its combined Austronesian and Bantu influences. The Malagasy language belongs to the South-East Barito subgroup of Austronesian languages in Borneo but its vocabulary contains a significant percentage of loanwords from the Sabaki subgroup of Bantu languages (primarily Comorian and Swahili) as well as other languages such as other Austronesian languages like Malay and Javanese.5 Genetically, the modern coastal populations of Madagascar have about about 65% east-African ancestry with the rest coming from groups closely related to modern Cambodians, while the highland populations have about 47% east-African ancestry with a similar ancestral source in south-east Asia as the coastal groups.6

More significantly however, is that this Bantu-Austronesian admixture occurred more the 600-960 years ago at its most recent, and most scholars suggest that the admixture occurred much earlier during the 1st millennium, with some postulating that it occurred on the Comoros archipelago before the already admixed group migrated to Madagascar.7 This combined evidence indicates that the population of Madagascar was thoroughly admixed well before the emergence of the earliest states in the interior and the dispersion of the dialects which make up the modern Malagasy language such as the Merina, Sakalava, Betsileo, etc.8 The creation of ethnonyms such as “Merina” is itself a very recent phenomenon associated with their kingdom’s 18th-19th century expansion.9

rice cultivation, 1896, madagascar , quai branly

Sculpture of a Zebu cow. 1935, Antananarivo, quai branly

Madagascar in the late 1st millennium, ancient sites and ‘ethnic’ groups. Map by G. Campbell

The emergence of kingdoms in Madagascar and the early Merina state from the 16th to the 18th century.

The first settlements in the interior highlands appear in the 12th-13th century at the archeological sites of Ambohimanga and Ankadivory. Similar sites appear across the island, they are characterized by fortified hilltop settlements of stone enclosures, within which were wooden houses and tombs, with inhabitants practicing rice farming and stock-breeding. Their material culture is predominantly local and unique to the island but also included a significant share of imported wares similar to those imported on the Swahili coast and the Comoros archipelago. These early settlements flourished thanks to the emergence of social hierarchies, continued migration and the island's increasing insertion into regional and international maritime trade.10

The history of the early Merina polity first appears in external accounts from the 17th century, that are later supplemented by internal traditions recorded later. Prominent among these traditions is Raminia, a person of purportedly Islamized/Indianized Austronesian origin with connections to Arabia and the Swahili coast, whose descendants (the Zafiraminia) settled at the eastern coast of the island. Among these was a woman named Andriandrakova who moved inland and married an autochtonous vazimba chief to produce the royal lineage of merina (Andriana).11 These traditions were initially interpreted by colonial scholars to have been literal migrations of distinct groups, but such interpretations have since been discredited in research which instead regards the traditions to be personifications of elite interactions between various hybridized groups with syncretic cultures, some of whom had been established on the island while others were recent immigrants.12

From the 16th century to the early 17th century, Madagascar was a political honeycomb of small polities. The central part of the highlands comprised several chiefdoms divided between the Merina and Betsileo groups, all centered at fortified hilltop sites. Intermittent conflicts between the small polities were resolved with warfare, alliances and diplomacy mediated by local lineage heads and ritual specialists. One of the more significant hilltop centers was Ampandrana, village southwest of the later capital Antananarivo. The elite of at Ampandrana gradually assumed a position of leadership from which came the future dynasty of Andriana, with its first (semi-legendary) rulers being; king Andriamanelo and his sucessor; king Ralambo. These rulers are credited with several political and cultural institutions of the early Merina state and establishing their authority over the clan heads through warfare and marital alliances. Ralambo's sucessor Andrianjaka would later found Antananarivo as the capital of the Merina state in the early 17th century. 13

Merina then appears in external accounts as the kingdom (s) of the Hova/Hoves/Uva/Vua, and was closely related to the export trade in commodities (mostly cattle and rice) and captives passing through the northwestern port of Mazalagem Nova that ultimately led to the Comoros archipelago, the Swahili coast and Arabian peninsula.14 The term ‘Hova’ is however not restricted to the Merina and is unlikely to have represented a single state as it was a social rank for the majority of highland Malagasy.15 Neverthless, its appearance sheds some light on the existence of hierachical polities in the interior.

One Portuguese account from 1613 mentions that “Some Buki [Malagasy] slaves are led from the kingdom of Uva, which is located in the interior of the island, and they are sold at Mazalagem to Moors from the Malindi coast [Swahili]”. It later describes these captives from Uva as resembling the "the palest half-breeds", but adds that some had curly hair, some straight hair, and some had dark skin. Mazalagem depended on the Merina state more than the reverse, as one account from 1620 "When I asked a negro from Mazalagem if his fellow-countrymen used to go and trade at Vua, he replied that the people from Mazalagem no longer go there since the people of Vua, who are very wicked, had stripped them of their wares and their silver and had killed a great number of their people". Neverthless, trade continued as one account from the late 17th century describes 'Hoves' coming to Mazalagem Nova with "10,000 head of cattle and 2 or 3,000 slaves”.16

Ruins of Mazalagem Nova, the 17th century town displaced the earlier town of Lagany as the main entreport for overland trade. While Mazalagem’s prosperity was largely tied to its virtual monopoly over the trade from the interior, it was only one of about 40 towns along the northern coast, most of which weren’t economically dependent on trade from the interior.

Read more about the history of the Swahili city-states of Madagascar here:

street scene in Mahajanga (Majunga) in 1945, quai branly. This town suceeded Mazalagem in the 18th century and remained Merina’s principal port in the west until the kingdom’s collapse.

These accounts don't reveal much about the internal processes of the Merina state, save for corroborating internal traditions about the processes of the kingdom's expansion, its agro-pastoral economy and its gradual integration into maritime trade in the 17th and 18th century. The population growth in central Merina compelled its rulers to expand the irrigated areas, which were mostly farmed by common subjects, while the royal estates were worked by a combination of corvee labour and captives from neighboring states. The most significant ruler of this period was king Andriamasinavalona (ca. 1675-1710) who expanded the borders of the kingdom, created more political institutions and increased both regional and coastal trade. He later divided his realm into four parts under the control of one of his sons, but the kingdom fragmented after his death, descending into a ruinous civil war that lasted until the late 18th century.17

In 1783, the ruler of the most powerful among the four divided kingdoms was Andrianampoinimerina . He negotiated a brief truce of with the other kings, fortified his dependencies, purchased more firearms from the coastal cities, and created more offices of counsellors in his government.18 In 1796 he recaptured Antananarivo, and after several campaigns, he had seized control of rest of the divided kingdoms, creating a sizeable unified state about 8,000 sqkm in size. It was under the reign of his sucessor Radama (r. 1810-1828) that the kingdom greatly expanded to cover nearly 2/3rds of the island (about 350,000-400,000 sqkm) through a complex process of diplomacy and warfare, conquering the Betsileo states by 1822, the Antsihanaka states in 1823, the sakalava kingdom of Iboina in 1823, and the coastal town of Majunga in 1824.19

Radama's rapid expansion brought Merina into close contact with the imperial powers of the western Indian ocean, primarily the French in the Mascarene islands (Mauritius & Reunion), and the British who ships often stopped by Nzwani island20. The intersection of Radama's expansionist interests and British commercial and abolitionist intrests led to the two signing treaties banning the export of slaves from regions under Merina control in exchange for British military and commercial support. Slaves from Madagascar comprised the bulk of captives sent to the Mascarene plantations in the 18th and early 19th century, some of whom would have come from Merina along with the kingdom's staple exports of cattle, rice and other commodities.21

However, competing imperial interests between the Merina, British and French compelled Radama to adopt autarkic policies meant to decrease his empire's reliance on imported weaponry and shore up his domestic economy. His policies were greatly expanded under his sucessor, Queen Ranavalona (1828-1861) and it was during their respective reigns that Merina was at the height of its power.22

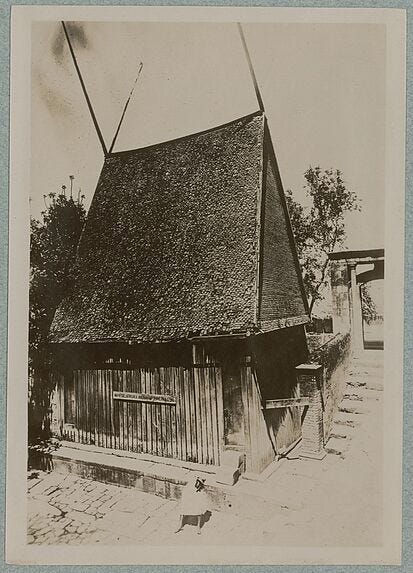

one of the residences of King Andrianampoinimerina within the Rova of Antananarivo, built in the traditional style. photo ca. 1895, quai branly

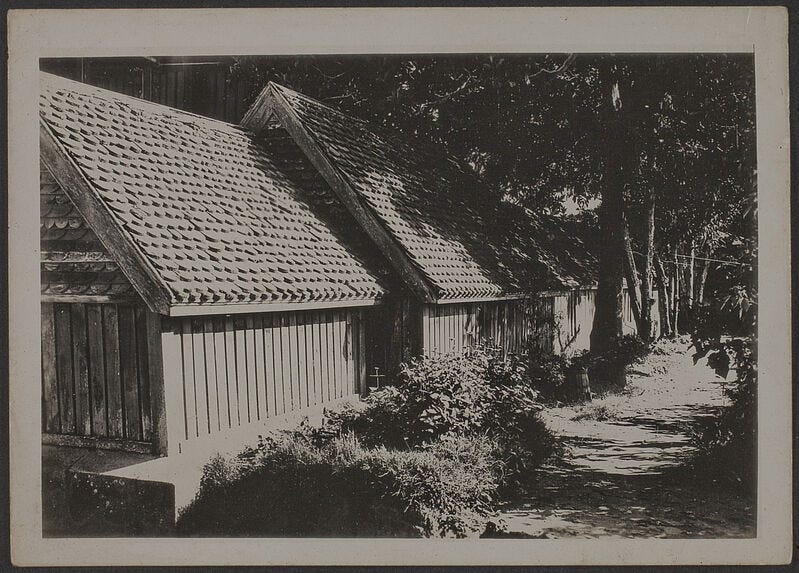

The seven tombs where the remains of king AndrianJaka and his descendants lie, Antananarivo, Madagascar. photo ca. 1945, quai branly. Originally built in the 17th/18th century, reconstruction was undertaken in the mid 19th century.

Expansion of the Merina kingdom in the early 19th century. Maps by G. Campbell

State and Society in early 19th century Merina: Politics, Military and the industrial economy.

The government in Merina was headed by the king/Queen, who was assisted by a council of seventy which represented every collective within the kingdom, the most powerful councilor being the prime minister. Merina's social hierachy was built over the cultural institutions that pre-existed the kingdom such as castes and clan groups, with the noble castes (andriana) ruling over the commoner clans (foko) and their composite subjects (Hova), as well as the slaves (andevo). The kinsmen of the King received fiefs (menakely) from which was derived tribute for the capital and labour attached to the court. The subjects often came together in assemblies (fokonolona) to enact regulations, and effect works in common such as embankments and other public constructions, and to mediate disputes.23

Both the Merina nobility and the subjects attached great importance to their ancestral lands (tanindrazana) controlled by clan founders (tompontany). Links between the ancestral lands and clan are maintained by continued burial within the solidly constructed tombs that are centrally located in the ancestral villages and towns, including the royal capital where the Merina court and King's tombs have a permanent fixture since the 17th century. Additionally, the clan founders and/or elders were appointed as local representatives of the Merina monarchy, in charge of remitting tribute and organizing corvee labour (fanompoana) for public works as well as for the military.24

the Tranovola of Radama I, built in the hybridized architectural style that gradually influenced the royal architecture of Merina. photo ca. 1945, quai branly

the Manjakamiadana palace of Ranavalona built by Jean Laborde in 1840, and encased in stone by Ranavalona II. photo ca. 1895, quai branly.

Merina armies initially consisted of large units drawn from ancestral land groups and commanded by the clan elders. when assembled, they were led by a commander in chief appointed by the king. After 1820 Radama succeeded in forming a standing army using the fanompoana system, who were supplied with the latest weaponry and stationed in garrisons across the kingdom. Radama's standing force and the traditional army units controlled by elders were both allowed to be engaged in the export trade, sharing their profits with the imperial court and enforcing Merina control over newly conquered regions. Radama's syncretism of Merina and European cultural institutions encouraged the settlement of Christian missionaries and the establishment of a school system whose students were initially drawn from the nobility and military, but later included artisans and other subjects.25

Merina's economy was predominantly based on intensive riziculture and pastoralism, supplemented by the various handicraft industries such as cloth manufacture, and metal smithing. Merina was at the center of a long-distance trade network of exchanges that fostered regional specialization, each province had regulated markets, and exchanges utilized imported silver, and commodity currencies. After the breakdown in relations between Merina and the Europeans, which included several wars where the French were expelled from Fort Daughin in 1824, and Tamatave in 1829, king Radama embarked on an ambitious program of industrialization that was subsquently expanded by Queen Ranavalona. Merina's local factories which were staffed by skilled artisans and funded by both the state and foreign entrepenuers (such as Jean Laborde), they produced a broad range of local manufactures including firearms, swords, ammunition, glass, cloth, tiles, processed sugar, soap and tanned leather.

Factory building in Mantasoa, Madagascar ca. 1900, the town of Mantasoa was the largest of several industrial settlements and plantations set up during the first half of the 19th century in one of the most ambitious attempts at industrialization in the non-western world.

read more about it here:

The Merina state in the late 19th century: stagnation, transformation and collapse.

During Queen Ranavalona's reign, increasing conflicts between the court and the religious factions in the capital led to the expulsion of the few remaining missionaries and the expansion of the tangena judicial system to check political and religious rivaries. Ranavalona's reign was characterized by increased Merina campiagns into outlying regions, the corvee labour system which supplied the industrial workforce and military, and the transformation of domestic labour with war captives from neighboring states, as well as imported captives from the Mozambique channel26. Merina retained its position as the most powerful state on the island thanks in part to the growing power of the prime minister Rainiharo, its armies managed to repel a major Franco-British attack on Tamatave in 1845, and to expel French agents from Ambavatobe in 1855. Rebellions in outlying provinces were crushed, but significant resistance persisted and Merina expansion effectively ground to a halt.27

Tomb of Rainiharo constructed by Jean Laborde, photo ca. 1945 quai branly

After Ranavalona's death in 1861, she was suceeded by Radama II, her chosen heir who undid many of her autarkic policies and re-established contacts with the Europeans and missionaries who regained their positions in the capital. But internal power struggles between the Merina nobility undermined Radama's ability to maintain his authority, and he was killed in a rebellion led by his prime minister Rainivoninahitriniony in 1863. The later had Radama's widow, Rasoherina (r. 1863-1868), proclaimed as Queen, who inturn replaced him with the commander in chief Rainilaiarivony as prime minister in 1864. From then, effective government passed on to Rainilaiarivony, who occupied two powerful offices at once, reduced the Queen's executive authority and succeeded in ruling Merina until 1895, in the name of three queens that suceeded Rasoherina as figureheads; Ranavalona II (1868-1883), and Ranavalona III (1883-1897). 28

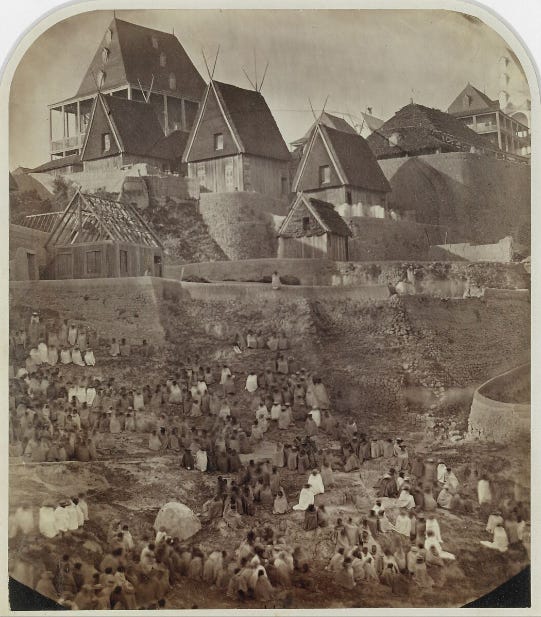

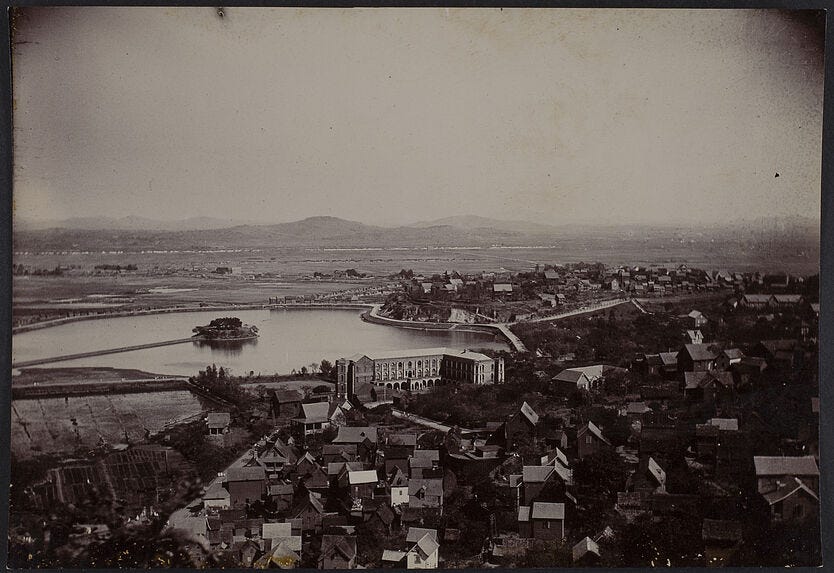

View of Antsahatsiroa, Antananarivo, Madagascar, 1862-1865

Tombs of King Radama I and Queen Rasoherina at the Rova of Antananarivo, photo ca. 1945, quai branly

Rainilaiarivony radically transformed Merina's political and cultural institutions, accelerating the innovations of the preceeding sovereigns. Merina's administration was restructured with more ministers/councilors under the office of the prime minister rather than the Queen, a code of laws was introduced to reform the Judicial system in 1868 and later in 1881, the military was rapidly modernized, and the collection of tribute became more formalized. Christianity became the court religion, mission schools were centralized, with more than 30,000 students in protestant mission schools alone by 1875.29

The increasing syncretism of Merina and European culture could be seen in the adoption of brick architecture in place of timber and stone houses, the uniformed military and the replacement of the sorabe script (an Arabo-Malagasy writing system) with the latin script as printing presses became ubiquitous. However, the evolution of Merina society was largely determined by internal processes, the court remained at Antananarivo which was the largest city with about 75,000 inhabitants, but besides a few coastal towns like Majunga and Tamatave, most Merina subjects lived in relatively small agricultural settlements under the authority of the clans and feudatories.30

Regionally, some of the political changes in Merina occurred in the background of the Anglo-French rivary in the western Indian ocean, which in Merina also played out between the rival Protestant and Catholic missions. As Rainilaiarivony leaned towards the British against the French, the latter were compelled to invade Merina and formally declare it a protectorate. In 1883, an French expedition force attacked Majunga and occupied Tamatave but its advance was checked in the interior forcing it to withdraw. A lengthy period of negotiations between the Merina and the French followed, but would prove futile as the French invaded again in December 1894. Their advance into the interior was stalled by the expedition's poor planning, only one major engagement was fought with the Merina army as the kingdom had erupted in rebellion. The Merina capital was taken by French forces in September 1895 and the kingdom formally ceased to exist as an independent state in the following month.31

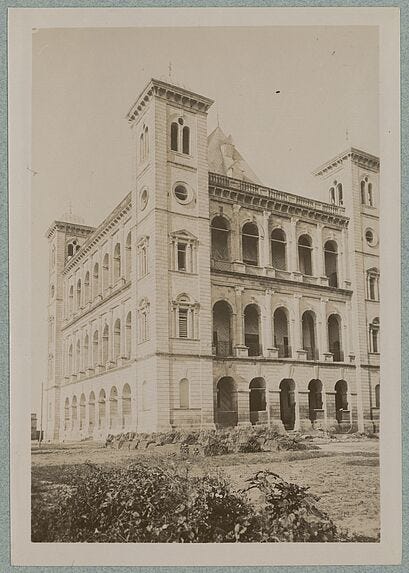

Palace of prime minister Rainilaiarivony, photo ca. 1895, quai branly

Antananarivo, ca. 1900, quai branly

In the early 19th century when the Merina state was home to one of the most remarkable examples of proto-industrialization in Africa.

read more about it on Patreon:

Early Exchange Between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World by G Campbell pg 195-204, A critical review of radiocarbon dates clarifies the human settlement of Madagascar by Kristina Douglass et al.

Early Exchange Between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World by G Campbell pg 206-214, Settling Madagascar: When Did People First Colonize the World’s Largest Island? by Peter Mitchell- and response: Evidence for Early Human Arrival in Madagascar is Robust: A Response to Mitchell by James P. Hansford et al.

The Austronesians in Madagascar and Their Interaction with the Bantu of the East African Coast by Roger Blench, The first migrants to Madagascar and their introduction of plants by Philippe Beaujard pg 174-185)

Early Exchange Between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World by G Campbell pg 213-220, The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Vol. 2 by Philippe Beaujard pg 374-378)

loanwords in Malagasy by Alexander Adelaar.

Early Exchange Between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World by G Campbell pg 244-250)

The Mobility Imperative: A Global Evolutionary Perspective of Human Migration By Augustin Holl pg 83-85, On the Origins and Admixture of Malagasy by Sergio Tofanelli et al pg 2120-2121, Malagasy Phonological History and Bantu Influence by Alexander Adelaar pg 145-146)

The first migrants to Madagascar and their introduction of plants by Philippe Beaujard pg 172-174, The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Vol. 2 by Philippe Beaujard pg 372-373

Desperately Seeking 'the Merina' (Central Madagascar) by Pier M. Larson pg 547-560

Early State Formation in Central Madagascar by Henry T. Wright et al pg 104-111, The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Vol. 2 by Philippe Beaujard pg 385-391

The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Vol. 2 by Philippe Beaujard pg 402-412)

The Myth of Racial Strife and Merina Kinglists: The Transformation of Texts by Gerald M. Berg pg 1-30, The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Vol. 2 by Philippe Beaujard pg 414-421

Unesco General history of Africa vol 5 pg 875-876, Early State Formation in Central Madagascar by Henry T. Wright et al pg 3)

Unesco General history of Africa vol 5 pg 862-866)

Desperately Seeking 'the Merina' (Central Madagascar) by Pier M. Larson pg 522-554

The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Vol. 2 by Philippe Beaujard of 560-561,615)

Unesco General history of Africa vol 5 877)

Sacred Acquisition: Andrianampoinimerina at Ambohimanga, 1777-1790 by Gerald M. Berg pg 191-211

Africa and the Indian Ocean World from Early Times to Circa 1900 by G. Campbell, pg 215 Unesco General history of Africa vol 5 pg 878

Slave trade and slavery on the Swahili coast by T Vernet , Madagascar and the Slave Trade by G Campbell

The Adoption of Autarky in Imperial Madagascar by G Campbell

The Cambridge History of Africa - Volume 5 pg 397)

Early State Formation in Central Madagascar by Henry T. Wright et al pg 12-14, Ancestors, Power, and History in Madagascar edited by Karen Middleton pg 259-265)

Radama's Smile: Domestic Challenges to Royal Ideology in Early Nineteenth-Century Imerina by Gerald M. Berg pg 86-91)

Of the 500,000 slaves on the eve of colonialism in Madagascar in 1896, more than 90% were Malagasy, while about 48,000 were Makuas from Mozambique; see: The African Diaspora in the Indian Ocean edited by Shihan de S. Jayasuriya, pg 96

The Cambridge History of Africa - Volume 5 pg 407-412, Africa and the Indian Ocean World from Early Times to Circa 1900 by G. Campbell pg 215-216)

The Cambridge History of Africa - Volume 5 pg 413-414

The Cambridge History of Africa - Volume 5 pg 413-417

Unesco general history of africa- Volume 6 pg 436-441)

An Economic History of Imperial Madagascar by G. Campbell pg 322-339)