A complete history of the old city of Gao ca. 700-1898.

Journal of African cities: chapter 12

Located in northeastern Mali along the bend of the Niger River, the old city of Gao was the first urban settlement in West Africa to appear in external accounts as the capital of a large kingdom which rivaled the Ghana empire.

For many centuries, the city of Gao commanded a strategic position within the complex political and cultural landscape of West Africa, as a cosmopolitan center populated by a diverse collection of merchants, scholars, and warrior-elites from across the region. The city served as the capital of the medieval kingdom of Gao from the 9th to the 13th century and re-emerged as the imperial capital of Songhay during the 16th century, before its later decline.

This article explores the history of Gao from the 8th to the 19th century, focusing on the political history of the ancient West african capital.

Map of west Africa’s empires showing the location of Gao1

The early history of Gao and its kingdom: 8th century to 13th century.

The eastern arc of the Niger River in modern Mali, which extends from Timbuktu to Gao to Bentiya (see map above), has been home to many sedentary iron age communities since the start of the Common Era. The material culture of the early settlements found at Tombouze near Timbuktu and Koima near Gao indicate that the region was settled by small communities of agro-pastoralists between 100-650CE, while surveys at the sites around Bentiya have revealed a similar settlement sequence.2

Settlements at Gao appear in the documentary and archeological record about the same time in the 8th century. The first external writer to provide some information on Gao was the Abbasid geographer Al-Yaqubi in 872, who described the kingdom of Gao as the "greatest of the reals of the Sudan [west Africa], the most important and powerful. All the kingdoms obey their king. Kawkaw [Gao] is the name of the town. Besides this there are a number of kingdoms whose rulers pay allegiance to him and acknowledge his sovereignty, although they are kings in their own lands.3

About a century later, Gao appears in the work of the Fatimid Geographer Al-Muhallabi (d. 990) who writes: “KawKaw is the name of a people and country in the Sudan … their king pretends before his subjects to be a Muslim and most of them pretend to be Muslims too." He adds that the King's royal town was located on the western bank of the river, while the merchant town called Sarnāh was on the eastern bank. He also mentions that the King's subjects were Muslims, had horses and their wealth included livestock and salt.4

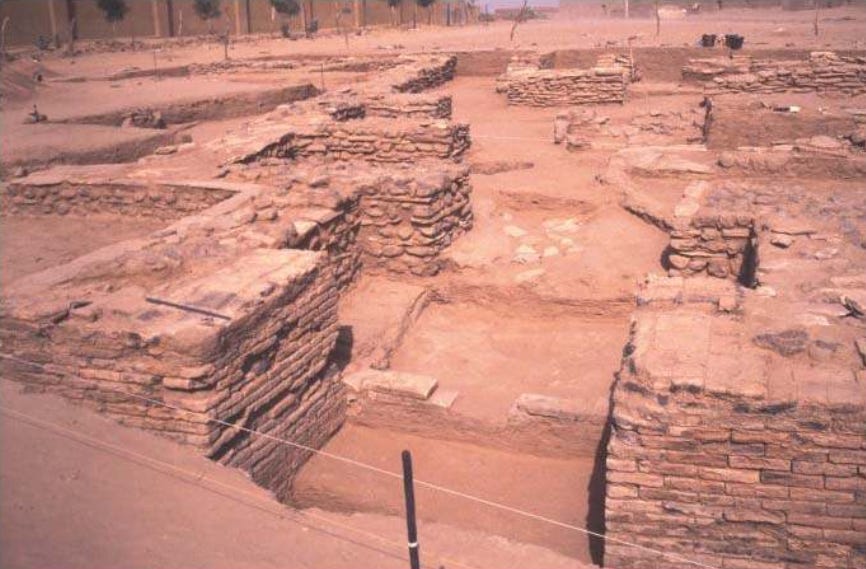

Excavations undertaken within and near the modern city of Gao by the archeologists Timothy Insoll5 and Mamadou Cissé at the sites of Gao Ancien and Gao Saney during the 1990s and early 2000s uncovered the remains of many structures including two large buildings and several residential structures at both sites built with brick and stone, as well as elite cemeteries containing over a hundred inscribed stele dating from the late 11th to the mid-14th century. Additionally, a substantial quantity of materials including pottery, and iron, objects of copper and gold with their associated crucibles, and a cache of ivory.6

remains of the ‘Long house’ and the ‘Pillar house’ Gao Ancien. The latter was initially thought to be a mosque, but it has no mirhab, which may indicate that it was an elite residence/palace like the former.

The bulk of the pottery recovered from excavations at Gao is part of a broader stylistic tradition called the Niger Bend Eastern Polychrome zone, which extends from Timbuktu to Gao to Bentiya, and is associated with Songhay speakers.7 Radiocarbon dates obtained from Gao-Saney and Gao Ancien indicate that the sites were occupied between 700-1100 CE with the largest building complexes being constructed between the 9th and 10th centuries, especially the ‘pillar house’ Gao-Ancien that is dated to between 900-1000 CE.8

The relative abundance of imported items at Gao (mostly glass beads, a few earthen lamps, fragments of glass vessels, and window-glass) as well as export items like gold and ivory, indicates that the city had established long-distance trade contacts with the Saharan town of Essouk-Tadmekka in the north9, which was itself connected to the city of Tahert in Algeria which was dominated by Ibadi merchants10. Many inscribed stele were also discovered at Gao Saney and Gao Ancien, most of which are dated to between the late 11th and mid-14th century and mention the names of several Kings and Queen-regnants who ruled the kingdom.

12th-century funerary stela from Gao-Saney11, a Commemorative stele for a Queen ‘M.s.r’ dated 111912, and a funerary inscription from Bentiya.

Stele from Gao of a woman named W.y.b.y. daughter of K.y.b.w, and another of a woman named K.rä daughter Adam. Moraes Farias suggests that her name was Waybiya (or Weybuy) daughter of Kaybu, and the second was Kara or Kiray, all of which are associated with Songhai names, titles, and honorifs, including those used by the daughters of the Askiyas who appear in the 17th century Timbuktu chronicles (Tarikh al-Sudan, and Tarikh al-Fattash).13

Before the recent archeological digs provided accurate radiocarbon dates for the establishment of Gao Saney and Ancien, earlier estimates were derived from the inscribed stele of both sites. Based on these, the historians Dierk Lange and John Hunwick proposed two separate origins for the rulers of Gao, by matching the names appearing on the stele with the kinglist of the enigmatic 'Za'/'Zuwa' dynasty that appears in the 17th century Timbuktu chronicles. Lange argued Gao’s rulers were Mande-speakers before they were displaced by the Songhay in the 15th century, while Hunwick argued that they were predominantly Songhay-speakers from the Bentiya-Kukiya region who founded Gao to control trade with the north and, save for a brief irruption of Ibadi-berbers allied with the Almoravids at Gao-Saney in the late 11th century, continued to rule until the end of the Songhai empire.14

However, most of these claims are largely conjectural and have since been contradicted by recent research. The names of the rulers (titled: Muluk for Kings or Malika for Queens) inscribed on the stele don't include easily recognizable ethnonyms (such as nisbas) that can be ascribed to particular groups, and their continued production across four centuries across multiple sites (Gao-Saney from 1042 to 1299; Gao Ancien from 1130 to 1364; Bentiya from 1182 to 148915) suggests that such attributions may be simplistic. The historian Moraes Farias, who has analyzed all of the stele of the Gao and the Niger Bend region in greater detail16, argues the rulers of the kingdom inaugurated a new system of government where kingship was circulated among several powerful groups in the area, and that the capital of Gao may have shifted multiple times.17

Furthermore, the archeological record from Gao-Saney in particular contradicts the claim of a Berber irruption during the late 11th century, as the site significantly predates the Almoravid period (ca. 1062–1150), having flourished in the 9th-10th century. Additionally, the pottery found at Gao Saney was different from the Berber site of Essouk-Tadmekka and North African sites, (and also the Mande site of Jenne-Jeno) but was similar to that found in the predominantly Songhay regions of the Niger Bend from Bentiya to Timbuktu, and is stylistically homogenous throughout the entire occupation period of both Gao Saney and Gao Ancien, thus providing strong evidence that the city's inhabitants were mostly local in origin.18

While the archeological record at the twin settlements of Gao ends at the turn of the 11th century, the city of Gao and its surrounding kingdom continue to appear in the historical record, perhaps indicating that there are other sites yet to be discovered within its vicinity (as suggested by many archeologists). The Andalusian geographer Al-Bakri, writing in 1068, describes Gao as consisting of two towns ruled by a Muslim king whose subjects weren't Muslim. He adds that "the people of the region of Kawkaw trade with Salt which serves as their currency" which he mentions is obtained from Tadmekka.19

A later account by al-Zuhri (d. 1154) indicates that the Ghana empire had extended as far as Tadmekka, in an apparent alliance with the Almoravids, but he says little about Gao20. The account of al-Idrisi from 1154 notes that the "town of Kawkaw is large and is widely famed in the land of the Sudan". Adding that its king is "an independent ruler, who has the sermon at the Friday communal prayers delivered in his own name. He has many servants and a large retinue, captains, soldiers, excellent apparel and beautiful ornaments." His warriors ride horses and camels; they are brave and superior in might to all the nations who are their neighbours around their land.21

Gao under the Mali empire: 14th to 15th century

During the mid-13th century, the kingdoms of Gao (as well as Ghana and Tadmekka) were gradually subsumed under the Mali empire. According to Ibn Khaldun, Mansa Sakura (who went on pilgrimage between 1299-1309) "conquered the land of Kawkaw and brought it within the rule of the people of Mali."22

This process likely involved the retention of local rulers under a Mali governor, as was the case for most provinces across the empire. According to the Timbuktu chronicles, the rulers of Gao revolted under the leadership of Ali Kulun around the 14th century. Ali Kulun is credited in some accounts with founding the Sunni dynasty of Songhay, while others indicate that the Sunni dynasty were deputies of Mali at Bentiya.23 Interestingly, the title of Askiya appeared at Gao as early as 1234 CE, instead of the title of Sunni, showing that some information about early Gao wasn’t readily available to the chroniclers of the Tarikhs.24

However, the hegemony of the empire of Mali in the Gao Region would continue well into the 1430s, as indicated by Mansa Musa's sojourning in the city upon his return from his famous pilgrimage of 1324. The Tarikh al-Sudan adds that Mansa Musa built a mosque in Gao, "which is still there to this day" [ie: in 1655], something that is frequently recalled in Gao’s oral traditions and was once wrongly thought to be the ruined building found at Gao-Ancien.25

When the globetrotter Ibn Batuta visited Gao in 1353, he mentioned that it was "one of the most beautiful, biggest and richest towns of Sudan, and the best supplied with provisions. Its inhabitants transact business, buying and selling, with cowries, as do the people of Mali" He adds that Mali’s hegemony extended a certain distance downstream from Gao, to a place called Mūlī, which may have been the name for Bentiya and a diasporic settlement of Mande elites and merchants. 26

Gao on the long-distance trade routes, map by Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias

astronomical manuscript titled "Kitâb fî al-Falak" (on the knowledge of the stars), ca. 1731, Gao, Mamma Haidara Library, Mali.

Gao as the imperial capital of Songhai from the 15th-16th century

Mali withdrew from the Niger Bend around 1434, and by the mid-15th century, the Suuni dynasty under Sulaymān Dāma had established its independence, his armies occupied Gao and campaigned as far as the Mali heartland of Mema by 1464. His successor, Sunni Ali Ber (r. 1464-1492) established Gao as the capital of his new empire of Songhai but maintained palaces across the region. Sunni Ali was succeeded by Askiya Muhammad, who founded the Askiya dynasty of Songhay and retained the city of Gao as his capital and the location of the most important palace. The city’s population grew as a consequence of its importance to the Askiyas, and it became one of the most important commercial, administrative, and scholarly capitals of 16th-century West Africa.27

The 1526 account of the maghrebian traveler Leo Africanus, who visited Gao during Askiya Muhammad’s reign noted that it was a “very large town" and "very civilized compared to Timbuktu", and that the houses of the king and his courtiers were of "very fine appearance" in contrast to the rest. He mentions that "The king has a special palace” and “a sizeable guard of horsemen and foot soldiers”, adding that "between the public and private gates of his palace there is a large courtyard surrounded by a wall. On each side of this courtyard a loggia serves as an audience chamber. Although the king personally handles all his affairs, he is assisted by numerous functionaries, such as secretaries, counsellors, captains, and stewards.”28

The various Songhay officers at Gao mentioned by Leo Africanus also appear extensively in the Tarikh al-Sudan, which also mentions that the Askiyas established "special quarters" in the city for specialist craftsmen of Mossi and Fulbe origin, that supplied the palace.29 According to the Tarikh al-Fattash, a ‘census’ of the compound houses in Gao during the reign of Askiya al-Hajj revealed a total of 7,626 such structures and numerous smaller houses. Given that each of these compound houses had about five to ten people, the population of the city's core was between 38,000 and 76,000, not including those living on the outskirts and the itinerant population of merchants, canoemen, soldiers, and other visitors.30

The city's large population was supplied by an elaborate system of royal estates established by the Askiyas along the Niger River from Dendi (in northern Benin) to Lake Debo (near Timbuktu). The rice and other grains that were cultivated on these estates were transported on large river barges along the Niger to Gao. The Timbuktu chronicles note that as many as 4,000 sunnu (600-750 tons) of grain were sent annually during the 16th century, carried by barges with a capacity of 20 tonnes.31

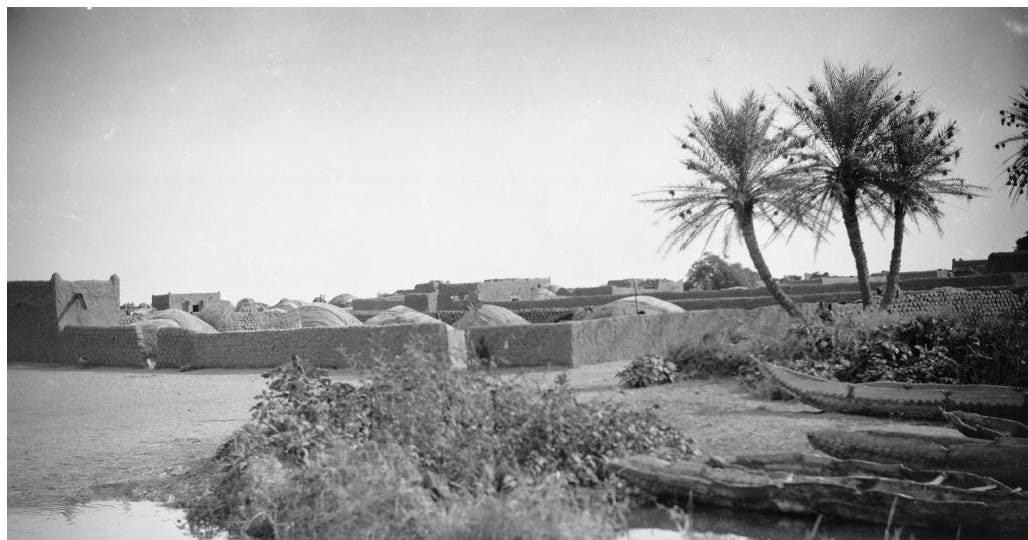

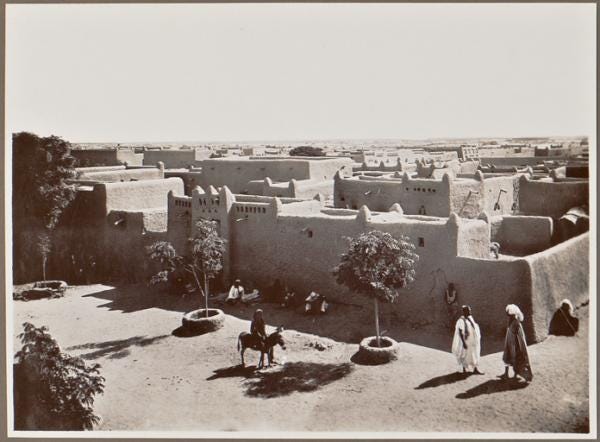

Gao, ca. 1935, ANOM.

Gao, late 20th century, Quai Branly

Map of Gao in 1951, showing Gao Ancien (broken outline), the old town, and the region of modern settlements (shaded). Map by T. Insoll.

The tomb of the Askiya, ca. 1920, ANOM.

Gao after the collapse of Songhay: 17th-19th century.

After the Moroccan invasion of 1591, many of the residents of Gao fled the city by river, taking the over 2,000 barges docked at its river port of Goima to move south to the region of Dendi. "none of its [Gao's] inhabitants remained there except the khatib Mahmud Darami, and the scholars, and those merchants who were unable to flee." This group opted to submit to the invaders, who subsequently appointed a puppet sultan named Sulayman son of Askiya Dawud, to ruler over Gao, while they chose Timbuktu as the capital of their Pashalik.32

Unable to defeat the Askiyas of Dendi as well as the Bambara and Fulbe rulers in the hinterlands of Djenne, the remaining Moroccan soldiers, who were known as the Arma, garrisoned themselves in Djenne, Timbuktu, and Gao and appointed their own Pashas. According to multiple internal accounts, the cities of Timbuktu and Gao went into steep decline during the late 17th to mid-18th century, largely due to the continued attacks by the Tuareg confederations of Tadmekkat and Iwillimidden in the hinterlands of the cities, which drove away merchant traffic and scholars. After several raids, Gao was occupied by the Iwillimidden in 1770, who later occupied Timbuktu in 1787, deposed the Arma, and abolished the Pashalik.33

Multiple accounts from the early 19th century indicate that Timbuktu and its surrounding hinterland were conquered by the Bambara empire of Segu around 1800, before the power was passed on to the Massina empire of Hamdullahi.34 However, few of the accounts describe the situation in Gao, which seems to have been largely neglected and doesn’t appear in internal accounts of the period.

It wasn't until the visit of the explorer Heinrich Barth in 1853 that Gao reappeared in historical records. However, the city was by then only a "desolate abode" with a small population, a situation which he often contrasted to its much grander status as the “ancient capital of Songhay”. Barth makes note of the mosque and mausoleum of the Askiya, where he set up his camp next to some tent houses, he also describes Gao's old ruins and estimates that the old city had a circumference of 6 miles but its section was by then largely overgrown save for the homes of the estimated 7,000 inhabitants including the tent-houses of the Tuareg.35

Barth’s illustration of the Askiya’s tomb on the outskirts of Gao in 1854 as viewed from his camp next to the Tuareg tent-houses, and a photo from 1934 (ETH Zurich) showing the same tomb as seen from the Tuareg tents.

Section of Gao showing the Tuareg tents within walled compounds. ETH Zurich, 1934.

Barth notes that the Songhay residents of Gao and its hinterlands comprised a “district” (ie: small kingdom) called “Abuba”, that had "lost almost all their national independence, and are constantly exposed to all sorts of contributions". According to local traditions collected a century later, the reigning arma of Gao (title: Gao Alkaydo) at the time was Abuba son of Alkaydo Amatu, who gave the kingdom its name. This indicates that Gao was still under the rule of the local Arma, who were independent of the then-defunct pashalik of Timbuktu, and were culturally indistinguishable from their subjects after centuries of intermarriage. These few Arma elites continued to collect taxes from the Songhay and itinerant merchants throughout the late 19th century, despite the presence of the more numerous Iwellemmedan-Tuareg on the city's outskirts.36

Gao was later occupied by the French in 1898, marking the start of its modern history37, and it is today one of Mali’s largest cities.

Gao in 1920, ANOM; 1934, ETH-Zurich.

Beginning in the 12th century, diplomatic links established between the kingdoms of West Africa and the Maghreb created a shared cultural space that facilitated the travel of West African envoys, merchants, and scholars to the cities of the Maghreb Marrakesh to Tripoli.

READ more about West Africa's links with the Maghreb on the AfricanHistoryExtra Patreon account:

Taken from Alisa LaGamma "Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara

Excavations at Gao Saney: New Evidence for Settlement Growth, Trade, and Interaction on the Niger Bend in the First Millennium CE by Mamadou Cissé, Susan Keech McIntosh pg 31, Archaeological Investigations of Early Trade and Urbanism at Gao Saney by M. Cisse pg 43-44, Bentyia (Kukyia): a Songhay–Mande meeting point, and a “missing link” in the archaeology of the West African diasporas of traders, warriors, praise-singers, and clerics by Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias prg 32-34

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 2)

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 8)

Islam, Archaeology and History: Gao Region (Mali) ca. AD 900 - 1250 by Timothy Insoll

Archaeological Investigations of Early Trade and Urbanism at Gao Saney by M. Cisse pg 47-57, 108, 120-138, 268-269)

Archaeological Investigations of Early Trade and Urbanism at Gao Saney by M. Cisse pg 63-265-267)

Archaeological Investigations of Early Trade and Urbanism at Gao Saney by M. Cisse pg 140, 270-271, Discovery of the earliest royal palace in Gao and its implications for the history of West Africa by Shoichiro Takezawa pg 10-11, 15-16)

Essouk - Tadmekka: An Early Islamic Trans-Saharan Market Town pg 273-280

Archaeological Investigations of Early Trade and Urbanism at Gao Saney by M. Cisse pg 22, 276-277)

Exposition al-Sahili by Musée National du Mali, 15-20 th March 2023.

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara by Alisa. LaGamma pg 122

Urbanism, Archaeology and Trade: Further Observations on the Gao Region (Mali), the 1996 Fieldseason Results by Timothy Insoll, Dorian Q. Fuller pg 156-159)

Excavations at Gao Saney: New Evidence for Settlement Growth, Trade, and Interaction on the Niger Bend in the First Millennium CE by Mamadou Cissé, Susan Keech McIntosh pg 12,

Essouk - Tadmekka: An Early Islamic Trans-Saharan Market Town pg 42, n.2

Arabic Medieval Inscriptions from the Republic of Mali: Epigraphy, Chronicles and Songhay-Tuareg History by P. F. de Moraes Farias

Excavations at Gao Saney: New Evidence for Settlement Growth, Trade, and Interaction on the Niger Bend in the First Millennium CE by Mamadou Cissé, Susan Keech McIntosh pg 12)

Archaeological Investigations of Early Trade and Urbanism at Gao Saney by M. Cisse pg 31, 41, 265, Islam, Archaeology and History: Gao Region (Mali) ca. AD 900 - 1250 by Timothy Insoll pg 46-47, Excavations at Gao Saney: New Evidence for Settlement Growth, Trade, and Interaction on the Niger Bend in the First Millennium CE by Mamadou Cissé, Susan Keech McIntosh pg 19-24, 30-32, for pottery from Essuk, see: Essouk - Tadmekka: An Early Islamic Trans-Saharan Market Town pg 144-148

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 22)

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 25-26

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 35)

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 94)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg xxxvii, Bentyia (Kukyia): a Songhay–Mande meeting point, and a “missing link” in the archaeology of the West African diasporas of traders, warriors, praise-singers, and clerics by Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias prg 84-87

The Meanings of Timbuktu by Shamil Jeppie,pg 101-102

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg 10)

The Travels of Ibn Battuta, AD 1325–1354: Volume IV by H.A.R. Gibb, C.F. Beckingham pg 971, Bentyia (Kukyia): a Songhay–Mande meeting point, and a “missing link” in the archaeology of the West African diasporas of traders, warriors, praise-singers, and clerics by Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias prg 69-70

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg xxxviii

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg 283 )

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg 147-148)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg xlix)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg pg l-li)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʿdi's Taʾrīkh Al-Sūdān Down to 1613, and Other Contemporary Documents by John O. Hunwick pg 190-191, 202)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4 pg 168-170)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 4 pg 178)

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa By Heinrich Barth, Vol. 5, London: 1858, pg 215-223)

Les Touaregs Iwellemmedan, 1647-1896 : un ensemble politique de la boucle du Niger · C. Grémont pg 337-346)

Saharan Frontiers: Space and Mobility in Northwest Africa edited by James McDougall, Judith Scheele pg 137