A history of the Gonja Kingdom: (1550-1899)

State and society in nothern ghana after the Mali empire's decline.

Near the end of the Mali empire, several sucessor states emerged across its southern frontier that inherited some of the empire's cultural and political institutions. One of the most remarkable heirs to the legacy of Mali was the Gonja kingdom in northern Ghana.

The kingdom of Gonja was an important regional power, linking the region of Mali to the Hausalands in northern Nigeria and the Gold-coast. Its cosmopolitan towns drew scholars and merchants from across west Africa, who left a significant intellectual and economic contribution to the region's history.

This article explores the history of the Gonja kingdom, including its political structure, intellectual history and architecture.

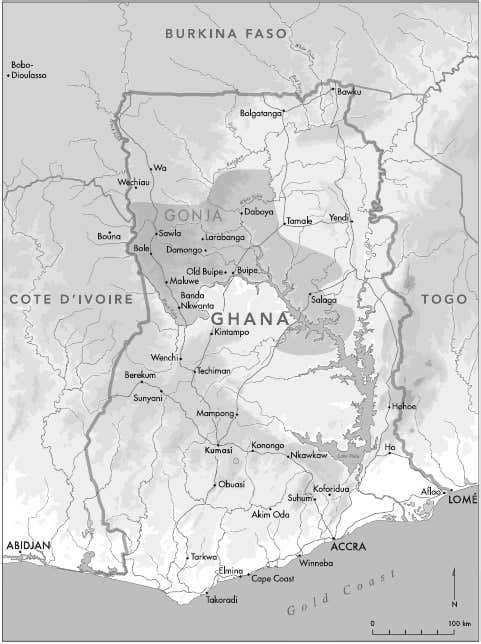

Map of Ghana showing the kingdom of Gonja at its height in the early 19th century1.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The early history of Gonja during the 15th and 16th century: from the Mali empire to the Volta Basin.

The region of northern Ghana where the kingdom of Gonja would later emerge was an important frontier for the old empire of Mali. It contained the rich gold mines of the Volta river basin, and the trading town of Begho established by merchants from Mali during the early 2nd millennium2. Beginning in the 18th century, the scholars of Gonja documented their kingdom’s history, their writings constitute some of west Africa’s most detailed internal accounts and allow us to reconstruct the region’s history.3

According to internal accounts, the Gonja kingdom was founded around the mid-16th century following a southern expedition from the Mali empire.4 The Mali emperor Jighi Jarra (this is likelyMahmud III r. 1496-1559 —who received Portuguese envoys from Elmina) requested for a tribute of gold from the ruler/governor of Begho, but the latter refused5. Jarra thus raised a cavalry force led by two princes, Umar and Naba and sent it to attack Begho, which was then sucessfully conquered. While Umar stayed at Begho, Naba advanced northwards to occupy the neighboring town of Buna, but instead of returning, he conquered the land east of the town, and founded the ruling dynasty of Gonja.6

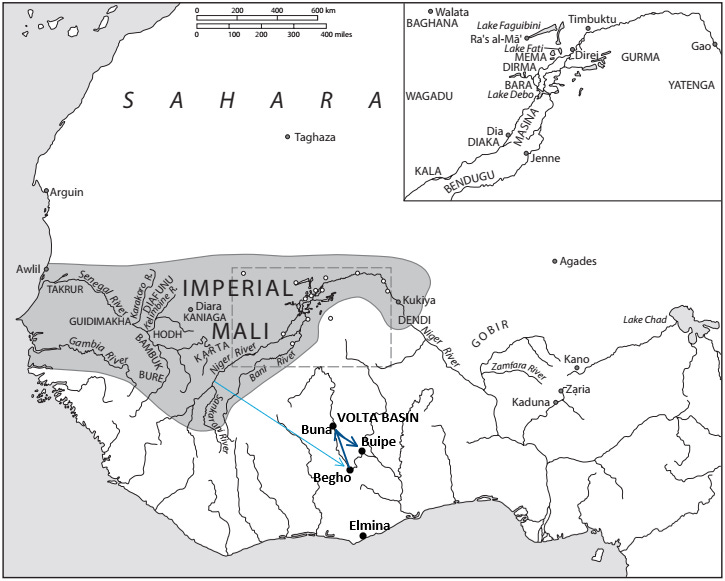

Purported migration of Gonja’s founders

For more on the Portuguese embassy to Mali and the conflict between Mali and Portugual see:

Traditions about immigrant founders from Mali are common among the origin-myths of the states in the Volta basin. While such traditions may not accurately recount real events, the Mali origin of some of the region’s elites is corroborated by their use of the clan names of Mande-speakers and the archeological evidence for pre-existing Mande settlements like Begho. Additionally, many of the scholars that appear in Gonja's history including those who wrote its chronicles were Wangara/Juula (ie Mande speakers), while the majority of the subjects in Gonja spoke the Guang-languages of the Akan family. 7

A more detailed internally written account known as the Kitab Gonja (Gonja chronicle) continues the early history of Gonja, identifying Naba as the first ruler of the kingdom from 1552 to 1582. Among Naba's allies was a Malam (teacher/scholar) named Ismā‛īl kamaghatay, and his son Mahama Labayiru (or Muhammad al-Abyad). This al-Abyad is credited with assisting Naba's sucessor Manwura (r. 1582-1600) while the latter was at war. Impressed by al-Abyad's assistance, Manwura adopted Islam and took on the name Umaru Kura. this King Umaru of Gonja was later suceeded by his brother Amoah (1600-1622) who is credited with constructing the first mosque at the town/capital called Buipe, and he also sent a representative to go on a pilgrimage to Mecca, thus taking on the honorific of Hajj.8

King Amoah was later suceeded by Jakpa Lanta (r. 1622–1666), a remarkable ruler who appears in several traditions as the "founder" of Gonja, or as the founder of a new dynasty. Jakpa is said to have come from ‘Mande’ (the Mali heartland) at the head of a band of horsemen, accompanied by his Malam named Fatigi Morokpe. He sucessfully conquered all the regions that became Gonja, upto the borders of Dagomba in the east and Asante in the south. Jakpa then settled at the town of Nyanga (or Yagbum), where he appointed his sons to govern each of the main provincial towns of Gonja, such as Tuluwe, Bole, Kpembe, Wasipe, and Kawsaw. Jakpa created the paramount office of Yagbumwura, which became the title of the king of Gonja, and was to rotate among the provinces.9

Conversely, the Gonja chronicle mentions that king Jakpa and his sucessor, king Sa'ara, launched several expeditions from their capital Buipe (rather than Yagbum). These included a sucessful invasion of Dagomba which seized the important town of Daboya, at the center of a salt-producing region. King Sa'ara was reportedly deposed in 1697 due to his ceaseless campaigns, he was initially suceeded by weak kings until the brief but sucessful reign of Abbas who sacked the town of Buna and Fugula in 1709. After the death of Abbas, central authority in Gonja was permanently weakened as each provincial chief retained power in their own capital. The now federated state, centered at Yagbum, consolidated its borders and would remain largely unchanged throughout most of the 18th and 19th century.10

Sketch showing the southern expansion of the Juula (in green) to the cities of Begho and Buna.11

Map of the Gonja kingdom by Jack Goody, showing the main provinces/chiefdoms

The government in Gonja during the 18th century.

The kingdom Gonja was a federated state, power was vested with the provincial chiefs, who owed ceremonial and ritual allegiance to the king at Yagbum. Effective authority lay in the hands of the chiefs of the roughly 15 provinces, the most prominent of whom were at Buipe, Bole, Wasipe, Kpembe, Tuluwe and Kawsaw12. Each of the chiefs had their own royal courts and armies, collected tribute and regulated trade. All chiefs were united in claiming descent from Jakpa, and were eligible for the role of king which was intended to be a rotating office, but was in practice often decided by the strongest chief.13

Gonja’s elite governed their subjects through representatives at the royal court and through matrimonial alliances with re-existing elites. The Gonja hierachy also included a class of Muslim scholars who formed an integral part of the state's political structure since its foundation. The kingdom was thus made up of three major social groups; the ruling elite called the Ngbanya, the Muslim scholars known as the Karamo and the rest of the subjects who were commonly known as the Nyemasi. The royals often resided in their capitals at some distance from the trading towns where the scholars lived, while the bulk of the subjects lived in the countryside.14

The archeological site of ‘Old Buipe’ in nothern Ghana has recently been identified as the location of the ancient town of Buipe, it was built around the late 15th century but abandoned in the 1950s.15 Excavations have uncovered complex structures in field A, C, D, E, and F of Old Buipe, which indicate that the site was relatively large urban settlement of significant political importance prior to the emergence of Gonja and during most the kingdom’s early history. The ruins of the site included several large courtyard houses with an orthogonal design, and flat roofs —some of which had an upper storey. The architecture of Old Buipe (which was also found at Gonja town of Daboya) challenges the mechanistic model of diffusion which assume that such building styles were introduced after the Islamization of the region.16

The largest structures excavated at Old Buipe were located in Fields; A, C and D, with a complex plan of juxtaposed rectangular rooms and courtyards, plastered cob walls (these are built with hardened silt, clay and gravel rather than brick), laterite floors, and a flat terrace-roof. The ruins of Field A included a large architectural complex of 16 rooms, built in the 15th cent and occupied until around the 18th century, while the ruins of Field C included a large structure of 14 rooms built in the 15th century, but abandoned in the early 16th century.17

Partially excavated ruins of a 15th century building complex at Field A, Old Buipe, Ghana (photo by photo Denis Genequand, drawing Marion Berti)

ruins of a 15th century building complex at Field C, Old Buipe, Ghana (photo by Denis Genequand)

ruins of a 15th century building complex at Field C, Old Buipe, Ghana (photo by photo Denis Genequand). Like the structure in A, this building was in use until around the 18th century.

The Scholars of Gonja

Both the written and oral traditions of Gonja often attribute king Naba and king Jakpa's military success to the role of their Malams; Ismail and al-Abyad (or Fatigi Morokpe). Gonja's scholars who descendend from these two figures formed distinct groups of urban-based imams, teachers and traders across the kingdom, all with varying relationships to the royal court.18 The scholary community of Gonja was part of a regional network that pre-existed the kingdom. According to the Kitab Gonja, town of Begho was the origin of Isma'il Kamagate and his son Muhammad al-Abyad19. Besides Begho, the scholars of Gonja were closely associated with their peers at Buna despite the town being a target of Gonja's attacks as it was virtually autonomous.20

Old mosque of Bouna (Côte d'Ivoire). Photo AOF, 1927

Like Begho, the town of Buna was Juula settlement and the capital of an independent chiefdom which pre-dated the founding of Gonja21. It became regional scholarly center, and by the 18th century, scholars from across west Africa converged at Buna, especially following the decline of Begho. These included Abū Bakr al-Siddīq of Timbuktu, who was a student in Buna around 1800, and mentioned several leading scholars of the town, including Shaykh ‘Abd al-Qādir Sankarī from Futa Jallon (in Guinea), Ibrāhīm ibn Yūsuf from Futa Toro (in Senegal) and Ibrāhīm ibn Abī’l-Hasan from Dyara (in Mali). Buna's scholary community was led by a local Juula named ‘Abdallāh ibn al-Hājj Muhammad Watarāwī.22

The relations between Buna and the Imams of Gonja, especially at Buipe and Bole, were close, and the authors of Gonja chronicle (Kitab Gonja) are among the scholars likely to have come from Buna23. The Kitab Gonja, was written in 1751 by the Gonja imam Sidi 'Umar b. Suma, who assumed office at Buipe in 1747. Umar was a descendant of al-Abyad and would be suceeded in office by his son 'Umar Kunandi b. 'Umar, who later updated the chronicle in 1764. Besides providing a detailed account of Gonja's history, the chronicle also records important events among Gonja's neighbors including the kingdoms of Asante, Dagomba, Bonduku, Mamprusi, Buna and Kong.24

19th century copy of the prayerbook 'Dalāʾil al-Khayrāt', written in northern Ghana, most likely by a scholar in Gonja or Dagomba, Ms. Or 6575, British library.25

19th century work titled kitāb al-balagh al-minan, (The Book of Attaining Destiny), written in northern Ghana, most likely by a scholar from Gonja or Dagomba, Ms Or. 6576, British Library. 26

The mosques of Gonja

There are four of Gonja old mosques still in use today, these include the mosques at Larabanga, Banda Nkwata, Maluwe and Bole. The construct of atleast two of these mosques; Larabanga and Banda Nkwata, is firmly dated to before 1900. While most local traditions date the construction of the Larabanga mosque to the 17th century, the present structure was built in the 19th century, with a few recent modifications27. The oldest mosque in Gonja was at Buipe, where the Kitab Gonja places its construction in the late 16th century, but the town was abandoned in the 1950s and the mosque is yet to be excavated.28 The mosque of Banda Nkwata was most likely built in the late 19th century29, while the mosques of Maluwe and Bole were built in the early 20th century, possibly ontop of older structures.30

The mosques of Larabanga, Banda Nkwanta, and Bole share a number of common elements: a square plan 10 to 12m wide, façades that are structured by buttresses surmounted by pinnacles and linked together by horizontal wooden poles, a prayer hall subdivided into three naves and three bays by four massive pillars and accessible through three doors, a terrace on the roof that is accessible by a staircase covered by a dome (the minaret-tower), and a protruding quadrangular mihrab sheltered at the base of another tower covered by a dome and situated in the centre of the qibla wall. The thick walls ensure the stability of the structure, while the wooden poles serve as scaffolding and decoration. Larabanga and Bole were built with cob, while the rest were built with mud-brick.31

Banda Nkwata mosque32

Larabanga mosque33

While islam played an important role in the kingdom’s social and political institutions, Gonja’s royal court was only partially Islamized, largely due to the accommodationist theology of the Wangara scholars who followed the Suwarian tradition of pacifism.34 Chiefs depended on both the imams and the earth-priests, and were only nominally Muslim despite claiming descent from the Islamized heartlands of Mali. The participation of the scholars in the state's creation and growth had earned them an influencial position in adminsitration but Gonja society’s differentiation into distinct social estates remained largely unchanged.35

Trade and Economy in Gonja

The kingdom of Gonja had a predominantly agro-pastoral economy, largely determined by its semi-arid ecology. The kingdom's towns, especially Buipe and Kaffaba were centers of significant craft industries including textile production and cloth dyeing, smiting, leatherworking, and salt mining. They posessed regular markets that were also connected to regional trade routes where external trade was undertaken by the old commercial diasporas of west Africa.36

The region of Gonja was at the crossroads of important trade routes which linked the gold and kola producing forests of the Voltaic basin to the trading hubs of Jenne to the north and Kano in Hausaland to the north-east. "Gonja" is itself a toponym of Hausa origin (ie: Gonjawa) which prexisted the kingdom and from which it would later derive its name. The chronicle Kano, mentions that the route from Kano to Gonja was first opened in the mid 15th century. Over the centuries, the commercial diasporas of the Hausa and the Wangara converged in Gonja and extended southward to Asante.37

Some of the towns in eastern Gonja such as Kafaba and Salaga pre-existed the founding of the kingdom and they included communities that claim to be of Hausa and Bornu origin. The Gonja chronicles also mention the presence of Hausa traders at Buipe whom came to buy Kola derived from Asante and Bunduku.38

As a result of the activities of external traders, the kingdom of Gonja appears on the 18th century maps made by the geographers De L'isle in 1707 and D'anville in 1749. The latter indicated Gonja as 'Gonge' and included its principal tows; Gbuipe as 'Goaffy', Tuluwe as 'Teloue' and Kafaba 'caffaba'. The names of the towns, which are rendered in Hausa, were transmitted by traders at the coast.39

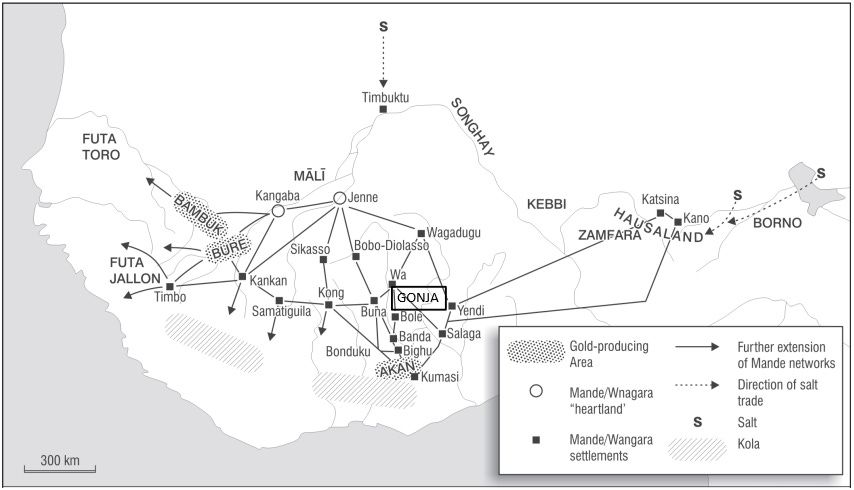

position of Gonja in the Mande trade network40

Gonja in the 19th century; from Asante domination to the onset of colonialism.

In the 1830s, the kingdom of Gonja became embroiled in a sucession crisis between Safo, the chief of Bole, and Kali, the chief of Tuluwe. The scholars of Buna agreed to mediate the dispute but ultimately failed, enabling Kali to defeat Safo's forces. After Safo's defeat his sons and followers fled to Wa, during which time, Kali's brief reign ended with the ascension of Saidu, the chief of Kongo . Saidu then requested ruler of Wa to repatriate Safo's followers but the latter refused. Saidu invaded Wa but was defeated, he then formed an alliance with the armies of Gyaman, but this too was defeated, forcing him to retreat to Daboya. The ruler of Wa then requested the Asante king Kwaku Dua (r. 1720-1750) to intervene, and the combined forces of Wa and Asante expelled Saidu from Daboya and killed him.41

Most of Gonja thereafter became a vassal of Asante, after several wars between most of the kingdom’s provinces. Written accounts from Gonja mention that the Asante first campaign into central and western Gonja occurred in 1732 (related to the abovementioned dispute with Wa), followed by an attack on Gonja’s eastern province of Kpembe in 1745 and 1751.42 The Asante invasion was initially perceived negatively by Gonja's scholars, especially the chronicler Sidi Umar who included an obituary of Opoku Ware that called the Asante king an oppressor that "harmed the people of Gonja". However, by the early 19th century, Gonja's scholars were praising the Asante for securing the region and protecting their interests at Kumase and at the town of Salaga.43

Founded around the late 16th century, Salaga was the trading town of the Gonja province of Kpembe and later became a trading emporium after its conquest by Asante. The cosmopolitan town with an estimated population of 40-50,000 during the early 19th century included diverse groups of scholars and merchants from across west africa that transformed it into a major center of education and trade. However, the brief disintegration of Asante following the British invasion of 1874 led to the independence of its northern vassals. The town Salaga expelled its Asante governors and gradually declined as it was displaced by other towns like Kitampo and Kete-Krachi, all of which were outside Gonja.44

a mosque at Salaga, ca. 1886-1890, Edouard Foa, Getty research institute

After it had thrown off Asante's suzeranity, Gonja had to contend with the growing power of the northern kingdom of Wa and the expansionist empire of Wasulu led by Samori Ture. The forces of Gonja’s nothern province of Kong had advanced towards Gonja’s border with Wa, prompting the ruler of Wa to assemble a large army and defeat Kong, annexing parts of the province45. This forced Jamani, chief of Kong, to ask Samori for support in his bid to retake his province and for the Gonja throne. In the late 1880s, Samori sent his son Sarankye Mori, who established himself at Bole after crushing local resistance, subsumed Wa, and briefly added most of Gonja to the Wasulu empire before Samori’s army fell to the French in 1898.46

In eastern Gonja, a conflict that begun in 1882 between the province of Kpembe and the kingdom of Dagbum, escalated into a major war by 1892 which destroyed Salaga.47 In 1894, Kpembe chief and the chiefs of Bole had signed treaty of ‘friendship’ with the British on the Gold coast, who were preparing to invade Asante in 1895 and didn’t want Gonja to aid Asante. The British presence angered the Germans who were now just east of Kpembe in what would later become Togo and considered Gonja a neutral zone. The Germans thus invaded Kpembe in 1896 and expelled its chief, around the same time that the British were occupying Asante and occupying Samori’s territories in Gonja by 1897. The British compelled most of Gonja’s chiefs into becoming part of the Gold-coast colony (Ghana) and the Germans gave up their claim of Kpembe. By 1899, Salaga formally came under British control, formally ending Gonja’s autonomy.48

Beginning in the late 18th century, Freed Slaves from the Americas resettled on west Africa’s coast and established themselves as influencial cultural intermediaries and wealthy merchants. These liberated Africans made a significant contribution to west-Africa’s economic and cultural growth in the 19th century, read more about them in this article:

Map by Marion Berti

Wangara, Akan and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. 1. The Matter of Bitu by Ivor Wilks pg 336-349 Outsiders and Strangers: An Archaeology of Liminality in West Africa By Anne Haour pg 68-73

Arabic Literature of Africa : The writings of Western Sudanic Africa, Volume 4 by J. Hunwick, pg 542-547

The Ethnography of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast by J. Goody pg 12, 54-55)

Wangara, Akan and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries II. The Struggle

for Trade by Ivor Wilks pg 468-472

Between Accommodation and Revivalism: Muslims, the State, and Society in Ghana from the Precolonial to the Postcolonial Era by Holger Weiss pg 53-54,

Between Accommodation and Revivalism by Holger Weiss pg 62-63, Jakpa and the Foundation of Gonja by D.H.Jones pg 6-12, Imams of Gonja The Kamaghate and the Transmission of Islam to the Volta Basin by Andreas Walter Massing pg 82-85

The Ethnography of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast by J. Goody pg 36-37, Between Accommodation and Revivalism by Holger Weiss pg 71)

Jakpa and the Foundation of Gonja by D.H.Jones pg 4-6, Between Accommodation and Revivalism by Holger Weiss pg 71)

Unesco General History of Africa vol 5, pg 339, The Ethnography of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast by J. Goody pg 11, 39, Jakpa and the Foundation of Gonja by D.H.Jones 17-20)

Foundations of Trade and Education in medieval west Africa: the Wangara diaspora.

As the earliest documented group of west African scholars and merchants, the Wangara occupy a unique position in African historiography, from the of accounts of medieval geographers in Muslim Spain to the archives of historians in Mamluk Egypt, the name Wangara was synonymous with gold trade from west Africa, the merchants who brought the gold, and the …

West African Kingdoms in the Nineteenth Century by Daryll Forde, P. M. Kaberry pg 188-189

Jakpa and the Foundation of Gonja by D.H.Jones pg 6)

Jakpa and the Foundation of Gonja by D.H.Jones pg 27-28, West African Kingdoms in the Nineteenth Century by Daryll Forde, P. M. Kaberry 186-187)

Excavations in Old Buipe and Study of the Mosque of Bole (Ghana, Northern Region): Report on the 2015 Season of the Gonja Project by Denis Genequand pg 28-29

Preliminary Report on the 2019 Season of the Gonja Project, Ghana by Denis Genequand et al. pg 287, Excavations in Old Buipe and Study of the Mosque of Bole (Ghana, Northern Region) by Denis Genequand et al. pg 26

For similar architectural complexes prior to Islamization, see: Oursi Hu-beero: A Medieval House Complex in Burkina Faso, West Africa edited by Lucas Pieter Petit

see the “Preliminary Reports” of the Gonja Project by Denis Genequand et al. from 2015-2020

West African Kingdoms in the Nineteenth Century by Daryll Forde, P. M. Kaberry pg 73-74)

Imams of Gonja The Kamaghate and the Transmission of Islam to the Volta Basin by Andreas Walter Massing pg 61 n.18

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 99, Wa and the Wala: Islam and Polity in Northwestern Ghana by Ivor Wilks pg 86)

Imams of Gonja The Kamaghate and the Transmission of Islam to the Volta Basin by Andreas Walter Massing pg 71-72

Between Accommodation and Revivalism by Holger Weiss pg 55)

Baghayogho: A Soninke Muslim Diaspora in the Mande World by Andreas W. Massing pg 914, Imams of Gonja The Kamaghate and the Transmission of Islam to the Volta Basin by Andreas Walter Massing pg 71

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg pg 99)

Architecture, Islam, and Identity in West Africa: Lessons from Larabanga By Michelle Apotsos pg 93-94, Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa By Stéphane Pradines pg 93-94)

The Ethnography of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast by J. Goody pg 37, Imams of Gonja The Kamaghate and the Transmission of Islam to the Volta Basin by Andreas Walter Massing pg 60

Preliminary Report on the 2016 Season of the Gonja Project by Denis Genequand pg 103)

Excavations in Old Buipe and Study of the Mosque of Bole by Denis Genequand pg 53-54, Preliminary Report on the 2017 Season of the Gonja Project by Denis Genequand pg 302)

Preliminary Report on the 2016 Season of the Gonja Project by Denis Genequand pg 96-108

Photos from wikimedia commons and by Denis Genequand

photos from wikimedia commons and Sue Milks on flickr

Between Accommodation and Revivalism by Holger Weiss pg 57-58)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 5 edited by J. D. Fage, pg 194)

West African Kingdoms in the Nineteenth Century by Daryll Forde, P. M. Kaberry pg 183-184)

The Ethnography of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast by J. Goody pg 7, Between Accommodation and Revivalism by Holger Weiss pg 97-99)

Accommodation and Revivalism by Holger Weiss pg 100-101, 109, n.311, Salaga: A Nineteenth Century Trading Town in Ghana by Levtzion Nehemia, pg 208 n. 3)

The Historian in Tropical Africa: Studies Presented and Discussed at the Fourth International African Seminar at the University of Dakar, Senegal 1961 by J. Vansina, R. Mauny, L. V. Thomas, Salaga: A Nineteenth Century Trading Town in Ghana Levtzion, Nehemia, pg 212-213)

map by Holger Weiss

Wa and the Wala: Islam and Polity in Northwestern Ghana by Ivor Wilks pg 100)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century by Ivor Wilks pg 20-21

The History of Islam in Africa edited by Nehemia Levtzion, Randall L. Pouwels pg 104-105)

Accommodation and Revivalism by Holger Weiss pg 110-112, 120-121, Salaga: A Nineteenth Century Trading Town in Ghana Levtzion, Nehemia, pg 218-222, 230-234)

West African Kingdoms in the Nineteenth Century by Daryll Forde, P. M. Kaberry pg 199, Wa and the Wala: Islam and Polity in Northwestern Ghana by Ivor Wilks pg 106)

Wa and the Wala: Islam and Polity in Northwestern Ghana by Ivor Wilks pg 121-123

Salaga: A Nineteenth Century Trading Town in Ghana by Levtzion, Nehemia, pg 236-240)

Salaga: A Nineteenth Century Trading Town in Ghana by Levtzion, Nehemia pg 242, Making History in Banda: Anthropological Visions of Africa's Past by Ann Brower Stahl pg 97-98

This is a professor-type comment, but I am struck in this essay by something that is a part of your other essays, it's just more notable here, which is that you don't actually do much historiographical discussion in your narration. e.g., you are often focusing on states or periods where there are some substantial questions about how much we know and how we know it--and when I look at your footnotes, you do a really interesting mixture of very old sources, of the major "first generation" of mainstream academic Africanists, and then a smattering of more recent archaeological and linguistic work often. But you don't talk about how you approach that mix of expertise, all of which presents at least a few issues. I really like the confidence and clarity of these essays, the straightforward narration of a knowable history, but I am a bit curious about how you see your approach to assembling the expert knowledge that informs these essays.

Thank you, really interesting to learn a more about that region of Africa.