Foundations of Trade and Education in medieval west Africa: the Wangara diaspora.

networks of gold and learning.

As the earliest documented group of west African scholars and merchants, the Wangara occupy a unique position in African historiography, from the of accounts of medieval geographers in Muslim Spain to the archives of historians in Mamluk Egypt, the name Wangara was synonymous with gold trade from west Africa, the merchants who brought the gold, and the mines from which they obtained it. But "Wangara" remained wrapped in mystery that confounded the external writers who described them and their confusion over the word’s usage, colored the medieval conception of west African societies.

In west Africa however, the Wangara were far from mysterious, but were the quintessential group of scholar-merchants who came to characterize the political and social landscape of the region. From their merchanttowns and scholarly centers that extended from Senegal to northern Nigeria, the Wangara oversaw a sophisticated commercial and intellectual network that greatly shaped the fortunes of pre-colonial west Africa. As one 17th century west African chronicle written by one of their scholars states "there was no land in the West that was not inhabited by the Wangara"

This article explores the history of the Wangara diaspora in west Africa, from their dispersion across west Africa to their legacy in scholarship and trade.

Map of west Africa showing the dispersion routes taken by the Jakhanke (yellow), Juula (green) and Wangarawa (red)

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Wangara Origins:

The name Wangara is one of several common ethnonyms including; Serakhulle; Juula; Jakankhe, which refers to closely related groups of northern Mande-speakers (Soninke and Maninka/Malinke languages) who were identified primarily by their involvement in long-distance trade and Islamic scholarship and are associated with the establishment of the medieval empires of Ghana and Mali. ‘Wangara’ originally denoted a loosely defined social-economic reality tied to the two factors of trade and learning, but later gave way to ethno-linguistic claims in some regions, while in other regions it was used by autochthonous groups to identify their communities of Mande scholar-merchants.1

The Wangara are known in external accounts as gold traders as early as the 11th century where they first appear in the descriptions of west Africa by al-Bakri as the "Gangara", and in al-Idrisi's texts who described the inland delta of the Niger as "the country of Wangara …its inhabitants are rich, for they possess gold in abundance." A 14th century account by Ibn Battuta identifies the "Wanjarat" town of Zaghari (Dia-Zagha/Dia-kha) that is home to many "black merchants" and scholars and is "old in Islam".2

In the mid-15th century, the Portuguese at El-mina (Ghana) had identified the “Mandingua” (ie Mande; a group which the Wangara belong) as their main suppliers of gold, and in 16th century external accounts, the Serakhullé are placed in the Senegambia region as important traders whose network extended to Egypt. The 17th century Timbuktu chronicle Tarikh al-fattash (whose author was a Wangara scholar) makes the distinction that the Malinke and Wangara are of similar origins but the former were Mali's soldiers while the latter were merchants, and other internal 17th and 19th century documents mention the “Wangarawa” as having arrived in the Hausalands between the 14th and 15th century.3

The heyday of the Wangara trade and scholarship prior to their dispersion was at the height of the Ghana and Mali empires between the 10th and 14th century when both Soninke and Malinke speakers inhabited a broad swathe of territory from the Senegal river to the Niger river. The Soninke in particular are associated with the Neolithic civilization of Dhar tichitt and the early urban clusters around the ancient cities of Dia and Jenne-jenno in the inner Niger delta region (see the green circle on the map) which grew to include the old towns of Kabara and Diakha (Jagha), while the Malinke are associated with the founding of Mali.4

Kābara was the dispersion point for Wangara scholars moving eastwards. These scholars became prominent in Timbuktu during the Mali era when the city is described as "thronged by sūdānī students, people of the west who excelled in scholarship and righteousness"; (sūdānī here being “black” west African in contrast to the bidan/“white” sanhaja-Berbers). The most prominent among whom was the scholar Modibbo Muhammad al-Kābari who moved to Timbuktu in 1446 along with 30 Kābara scholars and taught the (sanhaja) scholars Umar Aqit and Sidi Yahya, both of whose families were predominant at Timbuktu during the Songhay era. (the latter has a Mosque/school named after him).5

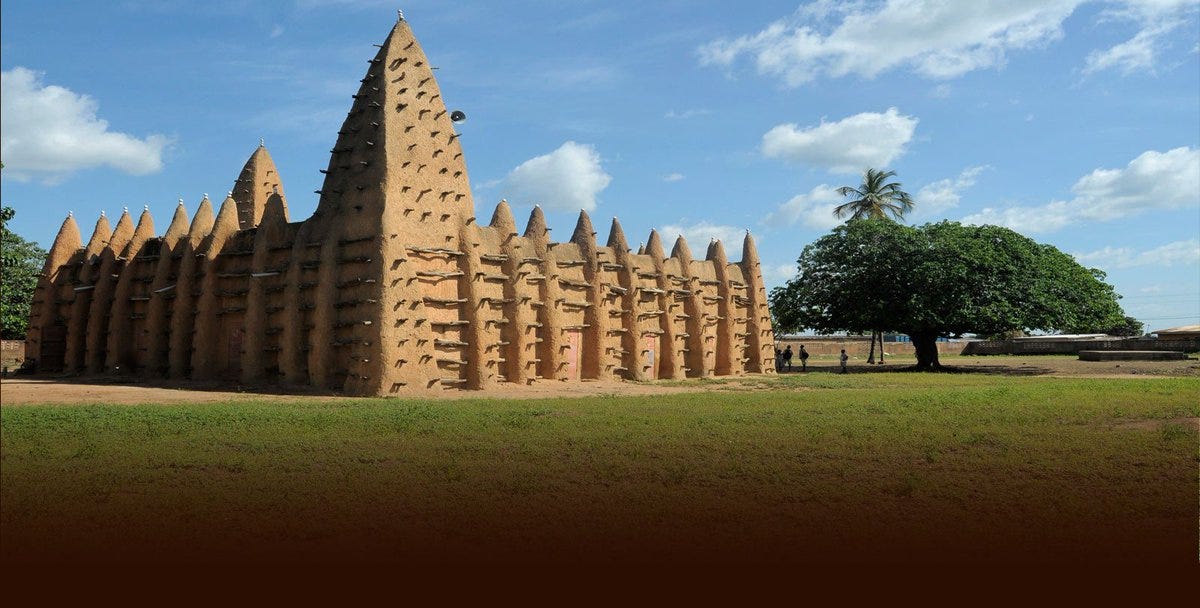

While Diakha became the point of dispersion for Wangara scholars and clerics moving south and west, and were known as Diakhanke/Jakhanke, they initially moved to Jenne (where virtually all scholars known have Wangara names) and later to Begho (where Jenne's merchants traded) and to the Senegambia regions. The most notable among whom was Muhammad Baghayogho al-Wangari of jenne (d.1593) who was also active in Timbuktu, the teacher of the famous Songhay scholar Ahmad baba as well as the Kunta scholars of the Sahel. The Baghayogho surname was prestigious across west africa including at Timbuktu where the Baghayogho family were the imams of the Sidi Yahya Mosque6, it also among the many soninke names of the Qadis of the jenne mosque, and appears among the Juula scholars who migrated southwards and who claim genealogical links to Jenne. Jenne was a major center of scholarship predating and rivaling Timbuktu with an estimated 4,200 scholars in the 12/13th century when its Great mosque was built, according to the 17th century Timbuktu chronicle tarikh al-sudan.7

the 15th century Sidi yahya mosque Timbuktu and the 13th century Great Mosque of Jenne.

A seminal figure among the Wangara scholars and merchants during their dispersion from Diakha was the scholar AI-Hajj Salim Suware. He is the subject of numerous hagiological references in writings that circulate widely among the Juula and Jakhanke groups and is said to have been born and educated in the city of Dia (Diakha or Ja) and travelled to mecca several times, after which he settled to teach in the city. The exact era in which he flourished is still a subject of debate with some scholars placing him in the 12th/13th century while others place him in the 15th/16th century.8

AI-Hajj Salim Suwari established, among Jakhanke and Juula alike, a pedagogical Suwari-an tradition which enjoined the repudiation of arms in favor of peaceful witness and moral example. His principle dicta which regulated the Wangara's relationships with non-Muslims, placed emphasis on pacifist commitment, education and teaching as tools of proselytizing, but it firmly rejected conversion through war (Jihad) which Suwari said was an interference with God's will.9 His teachings enabled the Jakhanke and Juula to operate within non-Muslim territories without prejudice to their distinctive Muslim identity, allowing them access to the material resources of this world (through trade) without foregoing salvation in the next.10

The old Wangara cities of Dia and Jenne

The arcs of Wangara dispersion

Trade appears to have been secondary to education/teaching according to most written and oral accounts among the Wangara diaspora which subscribed to the Suwarian tradition, as they focus not on those who went to do business, but on those who traveled to teach. Despite this emphasis on scholarship, many of the Wangara settlements (especially for the Juula groups) were established along gold trading routes, which betrays their commercial interests.11 Over the course of their migration, there were three common ethnonyms used for the Wangara scholar-merchants; in the Volta basin region (Burkina Faso to Ghana and ivory coast) they were called Juula (Dyula) which simply means merchant, while in the central Sudan (northern Nigeria and Niger) they were referred to as Wangarawa, and in the western-most region from Senegambia through Guinea to Sierra Leone, they are primarily identified as Jakhankhe. (although these terms attimes overlapped)12

The Southern expansion of the Juula

The earliest waves of expansion by the Juula following the southern direction into the Volta basin occurred in the 15th and 16th century with the establishment of the town of Begho by merchant-scholars from Jenne . According to a chronicle written in 1747 titled “Kitab Ghanja” written by Sidi Umar bin Suma -a direct descendant of the original Juula founders of Begho, the town of Begho was founded by a Mali general Nabanga, who had been sent to defend the declining empire's gold supplies, but Nabanga instead stayed there to found the kingdom of Gonja. The Timbuktu chronicle tarikh al-sudan on the other hand, simply mentions Begho as a mine frequented by Jenne traders. These account have been partially collaborated archeologically with the findings of Islamic material culture, burials and long distance trade goods in Begho dated to 1400-1700. Begho's collapse led to the dispersion of many of the Juula groups who are credited with the establishment of the towns of Bondouku, Salaga, Buna and Bole during the 17th/18th century.13

To the east of Begho was the 17th century kingdom of Dagomba (in northern Ghana), its non-Muslim King Na Luro (d.1660) is said to have invited the Juula scholar Abdallah Bagayogo from Timbuktu who built a mosque and school that was run by his son Ya'muru, the latter then taught the Dagomba prince Muhammad Zangina that became the kingdom's first Muslim ruler in 1700. A visiting north-African merchant in the 18th century described the Muslim kingdom of Dagomba and its characteristically Suwarian tradition of tolerance that "the Musselman and the Pagan are indiscriminately mixed that their cattle feed upon the same mountain, and that the approach of evening sends them in peace to the same village"14. A similar trajectory occurred in the kingdom of Wa (northern Ghana) where the Wangara scholar from the city of Dia named Ya'muru Tarawiri (who was the grandson of Suwari's student Bukari Tarawiri the 16th century Qadi of Jenne), got acquainted with prince Saliya of Wa and made Tarawiri the Wa kingdom's first imam.15

In other regions, the Juula were converted by their hosts rather than the reverse, including in the region surrounding the city of Bobo (southern Burkina Faso) and Tagara (northern Ghana). From the Juula’s perspective, this threat of backsliding necessitated the need for constant renewal from newer waves of immigrants, so the Juula’s Saganogo clan took on the role of renewers, initiating a wave of construction across the various Juula settlements with mosques and schools built at Kong in 1785, at Buna in 1795, at Bonduku in 1797 and at Wa in 1801. These cities became major centers of learning, especially Buna which the explorer Henrich Barth described in the 1850s that "a place of great celebrity for its learning and its schools, in the countries of the Mohammedan Mandingoes to the south."16

the juula city of Bonduku in Ivory coast and Wa Na’s residence in Ghana

The Juula established themselves in the Asante kingdom (central Ghana) during the 18th century. Some decades after the 18th century Asante conquest of northern states including Gonja (which is bitterly recounted in Sidi Umar's chronicle Kitab Ghanja mentioned above ). Umar's great-grandson Muhammad Kamagate eventually became a close confidant of the Asante king Osei Tutu, assumed the role of leader of the Juula quarter in Asante's capital Kumase and served as a go-between in the king Osei's correspondence with his Gonja subjects. The Juula merchant-scholar network in Kumase overlapped with other commercial diasporas including the Hausa.17

In some rare exceptions, the Juula accompanied military conquerors, as was the case with the Mande general Shehu Watara (d. 1745) who established the Kong kingdom between Ivory coast and Burkina Faso, and subsumed various already-established Juula settlements including at the cities of Kong, Bonduku and Bobo-Dioulasso. Despite the militant circumstances of its founding, Suwarian precepts were upheld in Kongo with one writer in 1907 noting that Kong was "a place distinguished, one might almost say, by its religious indifference, or at all events by its tolerant spirit and wise respect for all the religious views of the surrounding indigenous populations".18

the 18th century Juula mosques of Bobo-Dioulasso in Burkina Faso and Kong in Ivory coast

Eastern expansion of the Wangarawa

The eastern wave of the Wangara migration begun during the 14th century according to 17th and 19th century chronicles from the Hausaland which recount the arrival and influence of the Wangara scholar-traders on the political and commercial institutions of the region. In the city-state of Katsina during the mid 14th century a Wangarawa (Hausa for Wangara) named Muhammad Korau established a new dynasty, around the same time when a Malinke warlord named Usumanu Zamnagawa seized the throne of Kano and ruled between 1343-1349, but was succeeded by a Hausa ruler king Yaji (r. 1349-1385) under whose reign a group of 40 Wangara scholars are said to have come from Mali and influenced Yaji’s institution of Muslim administrative titles (imam and alkali). His second successor king Kanajeji (1390-1410) acquired cavalry equipment and chainmail from the Wangara, but his mixed military performance forced him to cut ties with the Wangara and reinstate traditional religion, his successor king Umaru (1410-1421) would instead turn to Bornu scholars and traders to play the role previously dominated by the Wangara.19

A chronicle written in 1650 from the city state of kano titled asl al-Wangariyyin alladhina bi-Kanu (The Origin of the Wangara in Kano) describes the journey of 3,636 scholars from the Mali empire, who travelled against the wishes its emperor in the year 1431, and arrived in Kano in the late 15th century. This group was led by Abd al-Rahmán Jakhite (Zaghayti /Diakhite; whose nisba denotes his origin from the city of Dia), the group was placed under the patronage of king Rumfa of kano (1463-1499) and remained prominent scholars in the city where they reportedly settled in the Madabo quarter.20

In the region of Borgu in northern Benin, the Wangara established themselves at an uncertain date during and after the fall of Songhai in the 16th century, becoming the dominant commercial diaspora in the towns of Djougou and Nikki by the 18th and 19th century where their networks overlapped with those of other commercial diasporas such as the Hausa and Yoruba.21

Western Expansion of the Jakhanke

The Jakhanke ethnonym represents the western wing of the northern Mande-speaking trade system, their geneological accounts (tarikhs) written in the 19th century say that under al-Hájj Sálim’s leadership, clerical learning shifted westward from the old city of Dia, toward the 17th century kingdoms of Bundu, Khasso, and Futa Jallon after fall of Mali. In the senegambia, the earliest jakhanke community was established at the town of Sutukho by the scholar Mama Sambu Gassama, this town also appears in several external (European) accounts from the 15th century as a major center of learning and trade where the Portuguese obtained a lot of gold (reportedly 5,000 ounces a year), and whose schools and private libraries are described as "monasteries". Sutukho was later abandoned in the 18th century when the Jakhanke moved to the town of Didecoto in Bundu kingdom, this state that was less militant than its peers due to the influence of Suwarian ideology carried by Didecoto’s main jakhankhe scholar Muhammad Fatima (d.1772) who also taught Bundu's rulers and influenced their adoption of Islamic offices in administration.22

Over the course of the 18th century, the Jakhanke expanded their clerical networks into the region of Futa Jallon led by the scholar al-Hajj Salim Gassama (b. 1730-d. 1824) who was born in Didecoto to Muhammad Fatima, and his name pays homage to the Suwarian founder. Gassama had travelled widely for advanced learning, including the cities of; Kounti (Gambia), Djenne and Massina (Mali), Kankan (guinea), and established several settlements for his students across the region before settling late in his life to found the city of Touba in Guinea in 1804.23

Touba became a major center of scholarship in the region and Touba's scholars eventually established other smaller centers of learning such as at Casamance (Senegal), Sutukung (Gambia) and Gbile (sierra-Leone). the Americo-Liberian Edward Blyden visited Gbile in 1872 where there was a ‘university’ run by the jakhanke scholar Foday Tarawali, cwhich Blyden called; “the Oxford of this region—where are collected over 500 young men studying Arabic and Koranic literature.24 The scholar's name Tarawiri (which in French is "Traoré) is a common nisba among the Jakhanke and Juula, and their settlement in Gbile (Kambia district, sierra Leone) marks the furthest expansion of the Wangara scholarly network

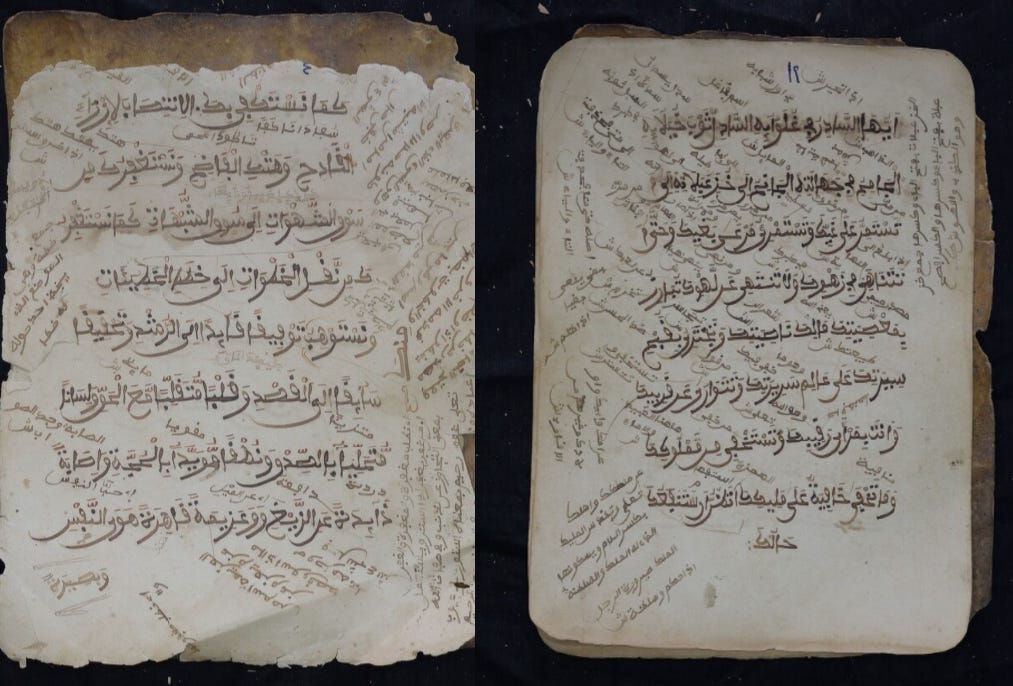

19th century copy of copy of Maqāmāt Al-Ḥarīrī with extensive in Soninke, Senegal25

Quranic manuscript with glosses in Soninke, from Casamance, Senegal26

Late 19th/early 20th century manuscripts from the private collection of the jakhanke descendants of Karang Sambu Lamin of Sutukung, stored in large metal boxes27

The Wangara as a commercial diaspora

The earliest mention of the Wangara’s trading activities comes from al-Bakri (d.1094), who describes them as a “non-Arab sūdān who conduct the commerce in gold dust between the lands” ie; from the goldfields of Bure and Bambuk (between Senegal and Mali) up to the markets of ancient Ghana. But despite his mention of Ghana’s scholars (presumably Wangara as well) in Andalusia (Spain) in the same text, his description of the Wangara as traders shows them still confined to their core territories. It wasn’t until the 15th century that accounts of Wangara traders appear outside their ethnic homeland as a commercial diaspora.

15th century accounts of the gold trade at the Portuguese El-mina castle credit the "Mandingua" (identified as Wangara) as the most prominent among the major trading groups that were responsible for the rapid influx of gold arriving at the fort, which in less than a decade had risen from 8,000 ounces in 1487 to 22,500 ounces in 1494, and prompted the Portuguese to send an envoy to Mali through the Wangara’s auspices in the 1490s.28

Contemporaneous accounts by external writers in north Africa also record the Wangara trading gold northwards through Jenne and Timbuktu and into north African markets, and by the 1540s, the Wangara had extended their trade westwards to the Gambia where the Portuguese had established a small trading town. An external account from 1578 notes that the Wangara travelled south from Gambia to obtain their gold on orders of the Mali emperor who'd also ordered the occupation of Begho (mentioned above) which ultimately led to the rapid decline of Elmina's gold trade.29

An example of a sophisticated Wangara network was the family of Karamo Sa Watara a resident of Timbuktu and Jenne. Karamo's brothers were established in Massina, Kong, and Buna and according to a biography written by his son, Karamo's business activities extended to the Hausalands where he was married to the daughter of a prominent local merchant Muhammad Tafsir in Katsina, to whom he sent a caravan of gold from Buna in the 1790s to which Tasfir paid for with Egyptian silks. Around the same time in 1790, a Wangara trader named aI-Hajj Hamad al-Wangari of Timbuktu organized a caravan of 50 camels carrying 4,000 ounces of gold and gum acacia, that was bound for the town of Akka in southern Morocco as payment for a large consignment of Flemish and Irish cloth.30

In the Hausalands, the Wangara were involved in the early establishment of the region's famous dyeing and textile industry as well as cotton growing, with al-Dimashqi (d.1327) referring to a Wangara state in near the Hausalands where "the Muslims inhabit the town and wear sewn garments" and where "cotton grows on great trees". The Wangara’s early association with characteristically Islamic chemises and mantles may point to the origin of the Hausa riga, and the wangara group accompanying Abd al-Rahmán Jakhite to Kano in the 1490s specialized in tailoring expensive gowns and its likely that his group joined earlier groups settled in Gobir and Katsina that were also involved in textile production at this early stage, although both activities would later be taken over by the Hausa.31

By the 18th century, trade in the Hausa city of Katsina was dominated by the Wangara and this continued through the 19th century despite the disastrous sack of their settlement at Yandoto during the Sokoto conquests that eventually led to their gradual displacement by other commercial diasporas such as the Agalawa-Hausa32. The explorer Heinrich Barth in the 1850s mentions that "almost all the more considerable native merchants in Katsena are Wangarawa", these traders occupied a ward which bore their name and one of its oldest quarters was called Tundun Melle.33

In the Volta region, the Asante's northern conquests in the 18th century are also associated with an influx in Kola-nut and Gold into Juula-dominated markets in Bonduku, Wa, Kong, Bobo and Nikki. Asante's extensive road network was grafted onto pre-existing regional trade routes especially those coming from the city of Salaga, and ultimately connecting the regions of Borgu and the Hausalands34

In Borgu, Wangara traders with northern-Mande clan names (jamuw/dyamuw) constituted some of the wealthiest traders and craftsmen especially the Kumate and Traore, the former coming to the Hausalands and Volta region in the 14th century from Mali, while the latter came from the same place around the 17th/18th century. The Kumate and Traore were also indigo dyers and were extensively engaged in textile trade, and while the Hausa dominated textile dyeing in the Hausalands, it was the Wangara that were the preeminent textile dyers and traders across the rest of the region from northern Benin through Burkina Faso to Côte d’Ivoire.35

Dye-pits outside Bobo

In the Senegambia region, the Jakhakhe were associated with closely related merchant groups and were also engaged in long distance trade themselves, despite being primarily identified with clerical/scholarly activity . Jakhanke traders dominated the regional commerce from Bundu in the 18th century, and were the wealthiest merchants in the Gambia according to 17th/18th century external accounts.36

In the region extending from Gambia to sierra Leone, the Jakhankhe are associated with crafts-groups of leatherworkers and blacksmiths called the garankew who are of soninke origin and accompanied (or more likely preceded) the migrating Jakhankhe clerics, and augmented the regions’ trade networks. Both explorers Mungo Park (1799) in Gambia and Thomas Winterbottom (1803) in Sierra Leone describe the trade and leatherworking activities carried out by "karrankea/garrankees" craftsmen that primarily involved making footwear and horse equipment.37

These merchant craftsmen were the southernmost community of a broader commercial diaspora, extending from Senegal to northern Nigeria, and from Sierra Leone to Ghana, making the Wangara diaspora the most widely attested community across West Africa.

Bonduku rooftops

AFRICAN DIASPORAS of scholars were also established in medieval EUROPE where their writings played a significant role in Europe’s political-religious movements. Read about the legacy of the ETHIOPIAN DIASPORA IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE on Patreon

If like this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

Outsiders and Strangers by Anne Haour pg 65-66)

The History of Islam in Africa pg 97, Beyond Jihad by Lamin Sanneh pg 83

The wangara an old soninke diaspora by Andreas W. Massing pg 282-285, The Role of the Wangara by Paul E. Lovejoy pg 175)

See a more detailed discussion in my article on

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John O. Hunwick pg 68-69)

Social history of Timbuktu by E. Saad pg 72

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John O. Hunwick pg xxviii-xxix,lvii, 18-19

Beyond Jihad by Lamin Sanneh, Al-Hajj Salim Suwari and the Suwarians by Ivor Wilks pg 45-46

Al-Hajj Salim Suwari and the Suwarians by Ivor Wilks 47

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 97-99)

Al-Hajj Salim Suwari and the Suwarians by Ivor Wilks pg 50

The walking Quran by R. Ware pg 93, Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 4. Writings of Western Sudanic Africa byJohn O. Hunwick. pg 539

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 99, Outsiders and Strangers by Anne Haour pg 71-72, The wangara an old soninke diaspora by Andreas W. Massing pg 297)

Al-Hajj Salim Suwari and the Suwarians by Ivor Wilks pg 40

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 100-101)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 101, 104)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 105)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 106)

Government In Kano by M. G. Smith pg 115-121)

Beyond Jihad by Lamin Sanneh pg 103-106)

Commerce caravanier et relations sociales au Bénin by Bregand Denise

Beyond Jihad by Lamin Sanneh pg 91-92, 94-100, Pragmatism in age of jihad by Michael A. Gomez pg 29-30, 65-67)

Beyond Jihad by Lamin Sanneh pg 132-143, 197

Beyond Jihad by Lamin Sanneh pg 164

Beyond Jihad by Lamin Sanneh pg 166)

Wangara, Akan and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries I by Ivor Wilks pg 338-339)

Wangara, Akan and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries II by Ivor Wilks 466-471)

The History of Islam in Africa pg 103)

Being and becoming Hausa by Anne Haour pg 189, The Role of the Wangara by Paul E. Lovejoy pg 185)

Sects & Social Disorder by Abdul Raufu Mustapha pg 29

Borgu and Economic Transformation 1700-1900 by Julius O. Adekunle pg 3)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century by Ivor Wilks pg 245)

Two Thousand Years in Dendi, Northern Benin by Anne Haour pg 300-304)

Merchants versus Scholars and Clerics in West Africa: Differential and Complementary Roles by Nehemia Levtzion pg 31-33, Pragmatism in the Age of Jihad by Michael A. Gomez pg 66-67)

Status and Identity in West Africa by by David C. Conrad pg 137-143

Always learn something new from you great information as usual the Wangara are such an interesting topic to study.

Very detailed as usual