A history of the Loango kingdom (ca.1500-1883) : Power, Ivory and Art in west-central Africa.

Africa's past carved in ivory

For more than five centuries, the kingdom of Loango dominated the coastal region of west central Africa between the modern countries of Gabon and Congo-Brazzaville. As a major regional power, Loango controlled lucrative trade routes that funneled African commodities into local and international markets, chief among which was ivory.

Loango artists created intricately carved ivory sculptures which reflected their sophisticated skill and profound cultural values, making their artworks a testament to the region's artistic and historical heritage. Loango ivories rank among the most immediate primary sources that offer direct African perspectives from an era of social and political change in west-central Africa on the eve of colonialism

This article explores the political and economic history of Loango, focusing on the kingdom's ivory trade and its ivory-carving tradition.

Map of west-central Africa in 1650 showing the kingdom of Loango

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The government in Loango

Beginning in the early 2nd millennium, the lower Congo river valley was divided into political and territorial units of varying sizes whose influence over their neighbors changed over time. The earliest state to emerge in the region was the kingdom of Kongo by the end of the 14th century, and it appears in external accounts as a fully centralized state in the 1480s. The polity of Loango would have emerged not long after Kongo's ascendance but wouldn't appear in the earliest accounts of west-central Africa.1

Loango was likely under the control of Kongo in the early 16th century, since the latter of which was nominally the suzerain of several early states in the lower Congo valley where its first rulers had themselves originated. Around the end of his reign, the Kongo king Diogo I (r. 1545-1561) sent a priest to named Sebastião de Souto to the court of the ruler of loango. Traditions documented in the 17th century credit a nobleman named Njimbe for establishing the independent kingdom of Loango.2

Njimbe built his power through the skillful use of force and alliances, conquering the neighboring polities of Wansi, Kilongo and Piri, the last of which become the home of his capital; Buali (Mbanza loango) near the coast. In the Kikongo language, a person from Piri would be called a Muvili, hence the origin of the term Vili as an ethnonym for people from the Kingdom of Loango3. But the Vili "ethnicity" came to include anyone from the so-called Loango coast which included territories controlled by other states.4

Kongo lost any claims of suzerainty over Loango by 1584, as the latter was then fully independent, and had disappeared from the royal titles of Kongo's kings. In the 1580s, caravans coming from Loango regularly went inland to purchase copper, ivory and cloth. And increasing external demand for items from the interior augmented the pre-existing commercial configurations to the benefit of Loango, which extended its cultural and political influence along the coast as far as cape Lopez.5

Once a vassal of Kongo, Loango became a competitor of its former overlord as a supplier of Atlantic commodities. After the death of Njimbe in 1565, power passed to another king who ruled over sixty years until 1625. Loango had since consolidated its control over a large stretch of coastline, established the ports of Loango and Mayumba, and was expanding southward. The pattern of conquest and consolidation had given Loango a complex government, centered in a core province ruled directly by the king and royals, while outlying provinces remained under their pre-conquest dynasties who were supervised by appointed officials.6

Colorized illustration of Olfert Dapper’s drawing of the Loango Capital, ca. 1686

By 1624, Loango expanded eastwards, using a network of military alliances to attack the eastern polities of Vungu and Wansi. These overtures were partly intended to monopolize the trade in copper and ivory in Bukkameale, a region that lay within the textile-producing belt of west-central Africa. This frontier region of Bukkameale located between Loango and Tio/Makoko kingdom, contained the copper mines of Mindouli/Mingole, and was the destination of most Vili carravans which regulary travelled through the interior both on foot and by canoe.7

The importance of Ivory, Cloth and Copper to Loango's rulers can be gleaned from this account by an early 17th century Dutch observer;

"[The king] has tremendous income, with houses full of elephant’s tusks, some of them full of copper, and many of them with lebongos [raphia cloth], which are common currency here… During my stay, more than 50,000 lbs. [of ivory] were traded each year. … There is also much beautiful red copper, most of which comes from the kingdom of the Isiques [Makoko] in the form of large copper arm-rings weighing between 1½ and 14 lb., which are smuggled out of the [Makoko] country".8

detail on a carved ivory tusk from Loango, depicting figures traveling by canoe and on foot. 1830-1887, No. TM-A-11083, Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen

Before the unnamed king's death in 1625, he instituted a rotation system of sucession in which each of the rulers of the four districts (Kaye, Boke, Selage, and Kabongo) within the core province would take the title of king. The first selected was Yambi ka Mbirisi from Kaye, who suceeded to the throne but had to face a brief sucession crisis from his rival candidates. The tenuous sucession system held for a while but evidently couldn't be maintained for long. In 1663, Loango was ruled by a king who, following a diplomatic and religious exchange with Kongo's province of Soyo, had taken up the name 'Afonso' after the famous king of Kongo.9

Afonso hoped his connection to Soyo would increase his power at the expense of the four other nobles meant to suceed him in rotation, since he’d expect to be suceeded by his sons instead. But this plan failed and Afonso was deposed by rival claimant who was himself deposed by another king in 1665. This started a civil war that ended in the 1670s, and when the king died, the rotation system was replaced by a state council (similar to the one in Kongo and other kingdoms), which elected kings. “they could raise one king up and replace him with another to their pleasure.”10

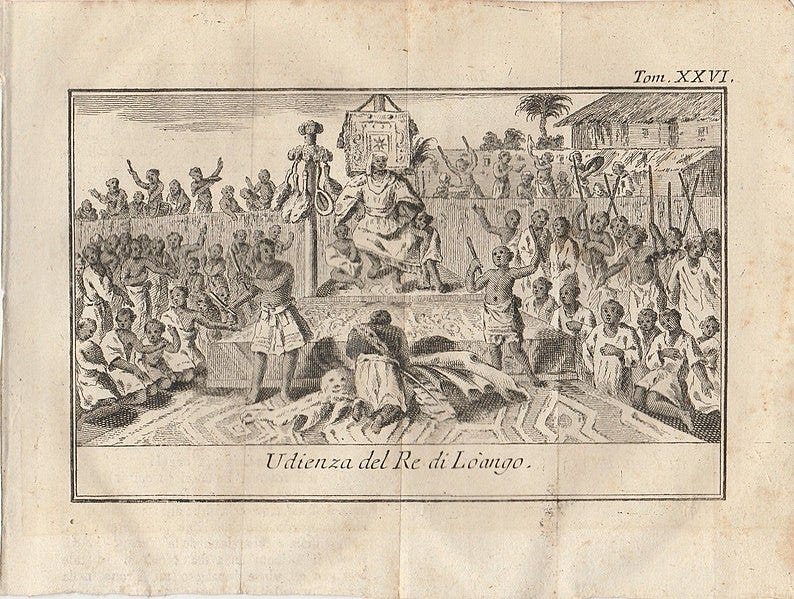

For most of the 18th century, the king's power was reduced as that of the councilors grew with each election. These councilors included the Magovo and the Mapouto who managed foreign affairs, the Makaka who commanded the army, the Mfuka who was in charge of trade, and the Makimba who had authority over the coast and interior. The king's role was confined to judicial matters such as resolving disputes and hearing cases.11

Detail of 19th century tusk, showing the emblem of the “Prime Minister of Loango ‘Mafuka Peter’” in the form of a coat of arms consisting of two seated animals in semi-rampant posture holding a perforated object between them. No. 11.10.83.2 -National Museums Liverpool.12

“Audience of the King of Loango”, ca. 1756, Thomas Salmon

After the death of a king, the election period often extended for some time while the country was nominally led by a 'Mani Boman' (regent) chosen by the king before his death. In 1701, no king had been elected despite the previous one having died nine months earlier, the kingdom was in the regency of Makunda in the interim. After the death of a king named Makossa in 1766, none was elected to succeed him in the 6 years that followed during which time the kingdom was led by two "regents". In 1772, Buatu was finally elected king, but when he died in 1787, no king was elected for nearly a century.13

From 1787 to 1870, executive power in Loango was held by the Nganga Mvumbi (priest of the corpse), another pre-existing official figure whose duty was to oversee the body of the king as he awaited burial. During the century-long interregnum, seven people holding this title acted as the leaders of the state. Their legitimacy lay in the claim that there was no suitable sucessor in the pool of candidates for the throne. The Nganga Mvumbi became part of the royal council which thus preserved its power by indefinitely postponing the election of the king. But the kingdom remained centralized in the hands of this bureaucracy, who exercised power in the name of the (deceased) king, collecting taxes, regulating trade, waging war and engaging with regional and foreign states.14

Descriptions of Loango in 1874 show a country firmly in the hands of the Nganga Mvumbi and his officers, although in the coastal areas, local officials begun to usurp official titles such as the Mafuk, which was sold to prominent families. New merchant classes also emerged among the low ranking nobles called the Mfumu Nsi, who built up power by attracting followers, dependents and slaves, as a consequence of increasing wealth from the commodities trade.15

detail of a 19th century Loango tusk depicting pipe-smoking figures being carried on a litter, No. TM-6049-29 -Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen

External Ivory trade from Loango

Loango, like most of its peers in central Africa had a mostly agricultural economy with some crafts industries for making textiles, iron and copper working, ivory and wood carving, etc. They had regular markets and used commodity currencies like cloth and copper and were marginally engaged in export trade. External trade items varied depending on demand and cost of purchase, but they primarily consisted of ivory, copper, captives, and cloth. These were acquired by private Vili merchants who were active in the segmented regional exchanges across regional trade routes, some extending as far as central Angola.16

detail on a 19th century Loango tusk depicting an elephant pinning down a hunter while another hunter aims a rifle at its head. No. 96-28-1 -Smithsonian Museum

The Vili's external trade was an extension of regional trade routes, no single state and no single item continuously dominated the entire region's external trade from the 16th to the 19th century. Cloth and salt was used as a means of exchange in caravans leaving Loango to trade in the interior. Among the goods acquired on these trade routes were ivory, copper, redwood and others. Most products were used for local consumption or intermediary exchange to facilitate acquisition of ivory and copper. Ivory was mostly acquired from the frontier regions, which were occupied by various groups including foragers ("pygmies"). The latter obtained the ivory using traps, and competitively sold it to both Loango and Makoko traders.17

The earliest external demand for Loango's ivory came from Portuguese traders. The Portuguese crown had attempted to monopolize trade between its own agents active along Loango's coast but this proved difficult to enforce as the Loango king refused the establishment of a Portuguese post in his region. This confined the Portuguese to the south and effectively edged them out of the ivory trade in favor of other buyers like the Dutch.18

Such was Loango's commitment to open trade that when the Dutch ship of the ivory trader Van den Broecke was captured by a Portuguese ship in 1608, armed forces from Loango intercepted the Portuguese ship, executed its crew and freed the Dutch prisoners.19 The Portuguese didn't entirely abandon trade with loango, and would maintain a token presence well in to the 1600s. They also used other European agents as intermediaries. Eg from 1590-1610, the English trader Andrew Battell who had been detained in Luanda, visited Loango as an agent for the governor of Luanda. He mentions trading some fabric for three 120-pound tusks and cloth.20

The Dutch become the most active traders on the Loango coast beginning in the early 17th century. The account of the Dutch ivory trader Pieter van den Broecke who was active in Loango between 1610 and 1612 provides some of the most detailed descriptions of this early trade. Broecke operated trading stations in the ports of Loango and Maiomba, where he specialized in camwood, raffia cloth and ivory, items that were cheaper and easier to store than the main external trade of the time which was captives. The camwood (used for dyeing cloth) and the raffia cloth (used in local trade) were mostly intermediaries commodities used to purchase ivory.21

Broecke and his agents acquired about 311,000 pounds of ivory after several trading seasons in Loango across a 5-year period. Most of the ivory came from private traders in the kingdom with a few coming from the Loango king himself. At the same time, Loango continued to be a major exporter of other items including cloth called makuta, of which up to 80,000 meters were traded with Luanda in 1611.22

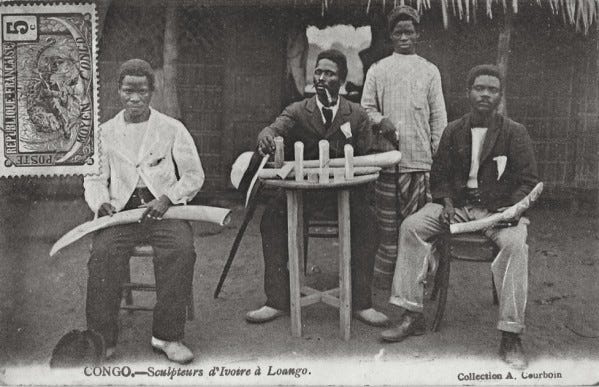

work made by ivory carvers in Loango, ca. 1910

The Dutch activities in Loango must have threatened Portuguese interests in the region, since the kings of Kongo and Ndongo sucessfully exploited the Dutch-Portuguese rivalry for their own interests. In 1624 the Luanda governor Fernão de Souza requested the Loango King to close the Dutch trading post, in exchange for buying all supplies of ivory, military assistance and a delegation of priests. But the Loango king rejected all offers, and continued to trade with the Dutch.23

Loango's ivory exports continued in significant quantities well into the late 17th century, but some observers noted that the advancement of the ivory frontier inland. Basing on information received from merchants active in Loango, the Ducth writer Olfert Dapper indicated that by the 1660s, supplies of ivory at the coast were decreasing because of the great difficulties in obtaining it.24

The gradual decline in external ivory trade coincided with the rise in demand of slaves.25 In the last decades of the 17th century, the Loango port briefly became a major embarkation point for captives from the interior, as several routes converged at the port.26 But Loango's port was soon displaced by Malemba, (a port of Kakongo kingdom) and later by Cabinda (a port of Ngoyo kingdom) in the 18th century, and lastly by Boma in the early 19th century, the first three of which were located on the so-called 'Loango coast'. Mentions of Loango in external accounts therefore don't exclusively refer to the kingdom, anymore than 'the bight of Benin' refers to areas controlled by the Benin kingdom.27

External Ivory trade continued in the 18th century, with records of significant exports in 1787, and the trade had fully recovered in the 19th century as the main export of Loango and its immediate neighbors after the decline of slave trade. The rising demand for commodities such as palm oil, rubber, camwood and ivory, reinvigorated established systems of trade and more than 78 factories were established along Loango's coast. Large exports of ivory were noted by visitors and traders in Loango and the kakongo kingdoms as early as 1817 and 1820, especially through the port of Mayumba.28

Vili carravans crossed territorial boundaries in different polities protected by toll points, and shrines with armed escorts provided by local rulers. Rising prices compensated the distances and capital invested by traders in acquiring the ivory whose frontier continued to expand inland. The wealth and dependents accumulated by the traders and the 'Mafuk' authorities at the coast gradually eroded the power of the central authorities in the capital. Factory communities created new markets for Vili entrepreneurs including ivory carvers who found new demand beyond their usual royal clientele. Its these carvers that created the iconic ivory artworks of Loango.29

Detail on a carved ivory tusk from Loango, ca. 1890, No. 71.1973.24.1 -Quai branly, depicting a European coastal ‘factory’

Carved ivory tusk from Loango, ca. 1906, No. IIIC20534, Berlin Ethnological Museum. depicting traders negotiating and giving tribute, and a procession of porters carrying merchandise.

The Ivory Art tradition of Loango

The carving of ivory in Loango was part of an old art tradition attested across many kingdoms in west central Africa.

For example, the earliest records of the Kongo kingdom mention the existence of carved ivory artworks that were given as gifts in diplomatic exchanges with foreign rulers. A 1492 account by the Portuguese chronicler Rui de Pina narrates the conversion of Caçuta (called a “fidalgo” of the Kongo kingdom) and the gifts he brought to Portugal which included “elephant tusks, and carved ivory things…” Another account by Garcia de Resende in the 1530s describes “a gift of many elephant tusks and carved ivory things..” among other items. Ivory trumpets and bracelets are also mentioned as part of the royal regalia of the king of Kongo.30

In Loango, the account of the abovementioned English trader Andrew Battell also refers to the ivory trumpets (called pongo or mpunga) at the King's court. He describes these royal trumpets as instruments made with an elephant's tusk, hollow inside, measuring a yard and a half, with an opening like that of a flute. He also mentions a royal burial ground near the capital that was encompassed by elephant tusks set into the ground.31

side-blown ivory Oliphant from the kingdom of Kongo, ca. 1552, Treasury of the Grand Dukes, italy

Ivory sculptors in Loango, ca. 1910

More detailed descriptions of Loango's ivory carving tradition were recorded in the 19th century. These include the account of Pechuël-Loesche's 1873 visit of Loango which includes mentions of ivory and wood carvings depicting the Loango king riding an elephant, that was a popular motif carved onto many private pieces, especially trumpets. Such instruments were costly and only used in festivals after which they were carefully stored away. Pechuël-Loesche believed these royal carvings inspired the pieces carved by private artists of whom he wrote "many have an outstanding skill in meticulously carving free hand”.32

Carved ivory tusk from Loango, ca. 1875, no. III C 429, Berlin Ethnological Museum. It depicts a succession of genre-like scenes arranged in rows spiraling around the longitudinal axis, it shows activities associated with coastal trading stations as well as hunting and processions of porters.

Artists in Loango were commisioned by both domestic and foreign clients to create artworks based on the client's preferences. For European clients, the carvers would reproduce a paper sketch on alternative surfaces such as wood using charcoal as ink, and then carefully render the artwork on ivory using different tools

One visitor in 1884 describes the process as such;

"On a spiral going all around the large tusk like the arrangement upon the column of trajan, there were depicted a multitude of figures (40 to 100) first incised with a sharp piece of metal; then, by means of two small chisels, sometimes also nails, a bas-relief was produced with a wooden mallet; and then the whole thing was smoothed off with a small knife.33

Elaborately carved ivory tusk depicting human and animal figures in various scenes, ca. 1890, No. 71.1966.26.16, 71.1966.26.15, 71.1890.67.1 Quai branly

The main motifs were human and animal figures depicted in scenes that revolve around specific themes. The human figures include both local and foreign individuals, who are slightly differentiated by clothing, activities and facial hair.34 The figures are always viewed from the side, in profile while the top often has a three-dimensional figure. Themes depicted include trade, travel, hunting in the countryside as well as activities around the factory communities. The latter scenes in particular reflect the semi-colonial contexts in which they were made, with artists exerting subversive criticism through selected imagery.35

While most of the extant Loango tusks in western institutions were evidently commissioned for European clients, the artists who carved the tusks asserted control over the narratives they depicted.36 Despite the de-centralized nature of the artists’ workshops across nearly a century, the narratives depicted remained remarkably consistent. The collector Carl Stecklemann who visisted Loango before 1889 suggests that the vignettes on the carved tusks chronicled “stirring events” in a great man’s career and were “carefully studied”, while another account from the 1880s suggests that they were “intended to tell stories and to point morals,” 37

One particulary exceptional tusk recreates four postcard images that were photographed by the commissioner of the tusk, German collector Robert Visser. In this tusk, the Loango artist skillfully returned his German surveyors’ surveillance by including a carving showing the latter taking a photo of the site.38 The Loango kingdom formally ended in 1883 when its capital was occupied by the French, but its art tradition would continue throughout the colonial and post-colonial era, with Vili artists creating some of the most exquisite tourist souvenirs on the continent.

detail of a 19th century Loango ivory tusk depicting the harvesting of palm oil, on the right is a postcard by Robert Visser in Loango, photos by Smithsonian39

Carved ivory tusk, made by a congolese artist, ca. 1927, No. TM-5969-203 Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen

The African religion of Bori and its Maguzawa Hausa practitioners, are some of the best-documented traditional african practices described by pre-colonial African historians. Kano's Muslim elite recognized the significance of the traditional Bori faith and the Maguzawa in the city-state's history and ensured that their contributions were documented.

Read more about it here:

If you like this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

Paths in the rainforests by Jan Vansina pg 155-156, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 64)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 65)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 65

Paths in the rainforests by Jan Vansina pg 202-204, Kongo: Power and Majesty By Alisa LaGamma pg 75

"Por conto e peso” by Mariza de Carvalho Soares pg 71-72, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 66, Paths in the rainforests by Jan Vansina pg 159)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 137-138, Paths in the rainforests by Jan Vansina pg 159)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 138-139, The External Trade of the Loango Coast, 1576-1870 by Phyllis Martin pg 17-18)

The Archaeology and Ethnography of Central Africa by James R. Denbow pg 145)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 177)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 178)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 249)

Trade, Collecting, and Forgetting in the Kongo Coast Friction Zone during the Late Nineteenth Century by Zachary Kingdon pg 29

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 305-306)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 306-307)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 345)

Paths in the rainforests by Jan Vansina pg 201-202)

"Por conto e peso” by Mariza de Carvalho Soares 63, 71, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 138

"Por conto e peso” by Mariza de Carvalho Soares pg 73-74)

Brothers in Arms, Partners in Trade: Dutch-Indigenous Alliances in the Atlantic World, 1595-1674 by Mark Meuwese pg 86-87)

"Por conto e peso” by Mariza de Carvalho Soares pg 74)

“Por conto e peso” by Mariza de Carvalho Soares pg 75)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 13,196,Por conto e peso” by Mariza de Carvalho Soares pg 76-77

Brothers in Arms, Partners in Trade: Dutch-Indigenous Alliances in the Atlantic World, 1595-1674 by Mark Meuwese pg pg 83-86, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by J. Thornton pg 134-136)

The External Trade of the Loango Coast, 1576-1870 by Phyllis Martin pg 71)

The Universal Traveller Or a Compleat Description of the Several Foreign Nations of the World, Volume 2 by Thomas Salmon pg 401-403

Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade by David Eltis pg 137-139,

Paths in the rainforests by Jan Vansina pg 204, A general collection of voyages and travels, digested by J. Pinkerton, Volume 16, pg 584-586)

African Voices in the African American Heritage By Betty M. Kuyk pg 32-33, Kongo: Power and Majesty By Alisa LaGamma pg 78, 80)

African Voices in the African American Heritage By Betty M. Kuyk pg 34-37, Kongo: Power and Majesty By Alisa LaGamma pg 79)

“Por conto e peso” by Mariza de Carvalho Soares pg 64)

“Por conto e peso” by Mariza de Carvalho Soares pg 74, The Portuguese in West Africa, 1415–1670 M. D. D. Newitt pg 185-186)

Kongo: Power and Majesty By Alisa LaGamma pg 80)

Kongo: Power and Majesty By Alisa LaGamma pg 81)

Trade, Collecting, and Forgetting in the Kongo Coast Friction Zone during the Late Nineteenth Century by Zachary Kingdon pg 22

A Companion to Modern African Art edited by Gitti Salami, pg 64

Nineteenth-Century Loango Coast Ivories by della Jenkins

Trade, Collecting, and Forgetting in the Kongo Coast Friction Zone during the Late Nineteenth Century by Zachary Kingdon pg 22-23

A Companion to Modern African Art edited by Gitti Salami, pg 63

I'm a Yombe from Loango , Congo. Glad to read this.

I'm a Yombe from Loango , Congo. Glad to read this.