A history of the Majeerteen Sultanate: 1700-1927.

Maritime trade and diplomacy in the northern Horn of Africa.

The north-eastern coast of Somalia was home to some of Africa's most dynamic maritime societies since antiquity. During the 18th century, the region was controlled by the Marjeerteen sultanate which became a major regional power linking the Somali mainland to the western Indian ocean.

From their fortified coastal towns, Marjeerteen’s rulers controlled a lucrative spice trade with southern Arabia, enforced maritime laws along a major shipping lane, and initiated diplomatic contacts with foreign states while halting the advance of colonial powers.

This article explores the history of the Majeerteen sultanate and its role as an important regional power in the northern horn of Africa from the 18th century to 1927.

Map showing the Majeerteen sultanate in north-eastern Somalia.1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

A brief history of the northern-eastern Somalia before the rise of Majeerteen.

The northern coast of the horn of Africa was home to several ancient settlements since antiquity. Archeological surveys of the settlements at Hafun, Alula and Cape Guardafui, revealed evidence of trade links between the settlements and the Sabean kingdom (in Yemen) and the Romans, including ruined buildings of sandstone and sherds of amphorae dated to the 2nd century.2 According to the 1st century guidebook, Periplus of the Erythraen Sea, there were several trading ports along the coast of northern Somalia, which was known as the Spice Coast, named after its aromatic and medicinal resins exports, notably frankincense.3

The empire of Aksum and the sultanate of Adal controlled parts of the northern horn of Africa’s coastline between late antiquity and the middle ages, but the region in which Majeerteen would emerge remained outside their political spheres. Around the 14th century, the north-eastern tip of the Horn was controlled by a vast confederation of Somali-speaking clan groups of the Darod family, of which the Harti sub-group were the most prominent. Among the Harti were the Majeerteen clan who were the nominal head of the confederation, but by the 18th century, this confederation had splintered into several independent states including Majeerteen.4

Coastal towns of the Majeerteen sultanate.5

The sultanate of Majeerteen.

The Majeerteen state was led by a ruler (variously refered to as Sultan or Boqor). while such titles carried little defined authority among some of the neighboring lineage groups6, the Majeerteen sultan exercised significant authority over the affairs of the state7. The Majeerteen ruler was assisted by a council of officers (including chiefs, qadis, etc) often appointed by himself8, taxes were paid by foreign merchants (often Arab and Indian) but not by his subjects9, he engaged with foreign diplomats as an independent sovereign albeit in the presence of his subordinate chiefs10, and he enforced laws regarding fort construction, security, marine salvage, and transhumance (pastoral rights on land, wells, etc).11

The capital/residence of Majeerteen sultan shifted with each successive ruler, it was initially at Bandar Meraya in the early 19th century12 before moving to Bargal and Bandar Gedid in the late 19th century13. Besides the capitals, a number of coastal towns were established along Majeerteen's shores during the 19th century including; Bandar Ziada, Bandar Cassim/Kasin (Bosaso), Kandala, Bandar Kor, Durbo, Filuk and Alula. Many of these were under the authority of princes and other kinsmen of the sultan.14 But the degree of control exercised over each subordinate chief, prince or kinsman of the Sultan was attimes tenuous, such as at the chiefs of Alula who often ‘rebelled’ against Majeerteen’s authority.15

As a coastal state, Majeerteen regulated the activities of foreign traders, travelers and shipwrecked sailors through the pre-existing somali social institution of abban ( mediator). It was the abban who took responsibility for a visitor’s security, acted as broker for business transactions, made introductions, and played the role of host and interpreter. In exchange, the abban levied a fee on all purchases made by the person under their protection, often in addition to presents and gifts. In the Majeerteen worldview, the abbans, who often came from the royal lineages, integrated guests into the society for the duration of their stay.16

The abban institution was utilized as a diplomatic system which mediated everyday interactions between the Majeerteen and envoys of foreign states including the Ottoman-Egyptian Khedive (which nominally claimed parts of the region), the Naqib of Mukalla (in Yemen), the sultan of Oman, and later European powers. Majerteen's regional diplomacy involved mutual recognition, gift giving and treaty signing, in a system of international relations common across the indian ocean littoral.17

Majeerteen rulers signed commercial treaties with the sultan of Oman (Zanzibar), as well as with the ruler of Mukalla. But as an independent state, Majerteen only accepted treaties which conformed to their own interests, and demonstrated this by turning down the Oman Sultan's request to build a his own lighthouse at Cape Guardafui. Such treaties and international relations strengthened and enhanced the Majeerteen sultans’ position as rulers in a contested political landscape.18

Among the foreign states which Majeerteen singed commercial treaties with were the British who had in 1839, occupied the port-city of Aden in Yemen. While Aden remained a relatively minor port in the first half of the 19th century, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, imbued the region with a strategic political and economic significance, leading to a significant increase in maritime traffic. What was once a six-month around Africa was transformed into a two-week steamship passage via the Red Sea.19

The precolonial commercial and diplomatic connections across the north-western Indian Ocean20

Trade and Economy of Majeerteen: Frankincense and Fort-building.

The growth of Aden and Muscat (Oman) increased maritime trade in the western Indian ocean ,creating more demand for Somali commodities including incenses, livestock, spices, coffee and hides. In 1837, an estimated 732 tonnes of Frankincense collected from the capital’s hinterland was sold at Merayah annually, more than half of which went to Bombay, while the rest went to the Red sea region and southern Arabia.21

By the 1870s, Majeerteen’s trade with the city of Aden alone amounted to around 5% of the city’s total imports valued at around 500,000 British Rupees per year by the 1870s, or about £25,000–50,000 sterling (about £30–60 million today), a figure that would double by the end of the century. While most of the export trade was in the hands of foreign merchants, a significant share was also undertaken by Majeerteen merchants. By the mid-19th century, local merchants owned 40 large merchant sailboats between them, each capable of carrying one hundred tons.22

Increasing numbers of local merchant vessels in Marjeerteen’s ports enabled its merchants to control more of its export trade to southern Arabia and sail southwards along Somali’s coast for trade goods. Majeerteen exports were sold across the entire stretch of Yemen's coast, the sultanate's traders travelled as far south as the Benadir coast between Mogadishu and Kismayo, to purchase grain for sale in Arabia. Their activities partly contributed to the agricultural boom of southern Somalia in the late 19th century.23

The uptick in commerce amplified pre-existing social patterns, trade routes and commercial institutions. Majeerteen aristocrats imported a range of markers of social distinction such as horses, cavalry warfare, forts and multi-story houses built in the style of the Hadhramaut. A visitor to Meraya in 1872 described the Majeerteen capital as occupied by about 700 inhabitants, with three mosques, a school and a multi-story palace of the Sultan built in the 1830s.24

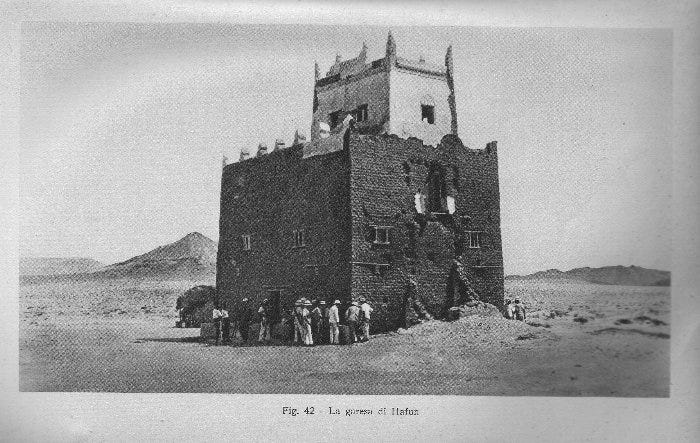

Majeerteen’s rising prosperity attracted diverse clan groups from the interior who built more settlements within the port towns. Conflicts between the new communities were resolved by the Majeerteen sultan, and through the construction of forts for each community that were used to store weapons, as well as to provide security for each community. Most of them were built using materials acquired from Aden, By 1906, Meraya had 4 forts, Ziada had 3 forts, Bosaso had 7 forts, Kandala had 6 forts, Durbo had 4 forts, Filuk had 4 forts, and Alula had 3 forts.25

Fort of Hafun, early 20th century, Archivio Aperto di Ateneo Università degli studi Roma Tre, Italy.

Majeerteen fort at Alula, ca. 1891, archivio fotografico

Majeerteen fort at Bender Gasim (Bandar Cassim), ca. 1891, archivio fotografico

House in Bender Gasim, ca. 1891, archivio fotografico

Majeerteen, the British and the founding of Hobyo: Diplomacy and Marine Salvage in 19th century Somalia.

After the opening of the suez, the entire Red Sea region became crowded with rival imperial superpowers competing to advance their interests. Despite is importance along a major shipping lane, the coast of Majerteen was unusually dangerous for navigation, its surrounding waters had reefs, and its habours weren’t deep enough for large ships. A traveler who visited the region in the late 1870s counted more than 6 steamships which had floundered there in less than 3 years between 1877-1880.26 The threat to foreign shipping created a need for laws regarding marine security and marine salvage, which Majeerteen regulary enforced through treaties.

In 1843, the shipwrecked crew of the British steamer memnon signed a treaty with the Majeerteen regent Nur Muhammad, in which the latter promised assistance for stranded British ships along the Majerteen coast in exchange for payment/stipends. But when a similar incident occurred to a stranded British ship in 1858, its crew rejected Majerteen's assistance, abandoned their vessel, and fled to Aden in their lifeboats.27

The crew then urged the British resident of Aden to avenge the "piracy" which they had claim to have suffered at the hands of the Majeerteen authorities, so the British bombarded the forts of Bandar Meraya. When a similar shipwreck occurred in 1858, the sultan's forces rescued its crew, sucessfully using them to initiate negotiations with the British. But in 1862 when a stranded steamer off the coast of Alula mistook the Majeerteen rescue crew to be raiders, a fight broke out which ended with the crew deserting its ship in the town of Baraada.28

The British blamed Majeerteen’s capital in retaliation to the incident at Baraada, and requested the reigning Sultan Mahmud Yusuf to find the culprits and execute them, threatening further bombardment if he didn't. The British chipped away some of the Sultan’s authority by forcing the latter to let the British search all its vessels and patrol its coasts, using the pretext of an anti-slavery treaty. (none of Majerteen's ports lay along any major slave route). More wrecks in the late 1870s near Alula exacerbated the divide between the town’s chief/governor, named Yusuf Ali, and Mahmud’s sucessor Sultan Uthman, as the former enriched himself and sought British recognition.29

Between the late 1870s and early 1880s, Yusuf had sucessfully rescued a few shipwrecked crews, which he sent to Aden and received recognition as “sultan” in return. But despite Yusuf's insubordination, sultan Uthman managed to retain most his authority with treaty signed between 1884-630. Yusuf then sought new allies in Zanzibar, whose sultan had claims to southern Somalia's coast, enabling Yusuf to establish his own state with its capital at Hobyo, about 200 miles south of Alula.31 A brief alliance between Yusuf and the Germans in 1885 ended when the latter pulled out of east Africa and were replaced by the Italians in 1889, with whom Yusuf immediately signed a treaty.32

Obbia (Hobyo) showing the Sultan’s residence and a fort. ca. 1924, archivio fotografico

Majeerteen between the anti-colonial movement of Abdille Hassan and the Italians.

With the British losing interest in Majeerteen’s coast in the late 1880s, and Italians arming Yusuf at Hobyo, sultan Uthman pragmatically chose to sign a protectorate treaty with Italy in 1889. To counter-balance the gradual loss of Majeerteen's power, Uthman begun selling some of the guns he bought (about 3,000 a year) to the anti-colonial movement of Muhammad Abdille Hassan in the hinterland33. He used the threat of Hassan's movement to sign an advantageous treaty with the Italians in 1901 that resulted in double the trade with Aden (about 5m lira ) and more guns for Majeerteen ( an estimated 20,000 rifles in 1901 alone).34

However, Uthman's involvement with Hassan's movement brought unwanted attention on Majeerteen's coast with frequent naval patrols by the British and Italians, both of whom claimed parts of northern Somalia. In 1904, a Majeerteen broker working for Hassan's movement was arrested by the Italians and revealed that Uthman supported Hassan. Yusuf Ali tried to capitalise on Uthman's fallout with the Italians by allowing the latter to use Hobyo as base against Hassan's movement. But Yusuf soon fell out with his allies, was deposed and Hobyo was occupied by the Italians. Uthman tried to restore his trust among the British and Italians by sending token support against Hassan, but once the latter was defeated in 1905, the Italians occupied Majeerteen port of Alula.35

In 1908, Hassan resumed his anti-colonial movement against the British, Italians and against the Majeerteen as well after he had fallen out with sultan Uthman. Faced with an invasion by Hassan’s forces, internal challenges to his authority and disapproving Italians, sultan Uthman ceded more of his power to the Italians in a 1909 treaty. Uthman assisted the Italians in fighting Hassan who was eventually defeated in 1921 and his movement dispersed36. Sultan Uthman later rebelled against Italian rule in1925 and made attempts to rebuild Hassan’s old forts in the interior, but his forces eventually fell to the Italians in 1927, formally marking the end of Majeerteen.37

Bender Cassim in 1938, archivio fotografico.

What was the extent of pre-colonial African knowledge about their own continent? In medieval north-east Africa, visitors from the Kingdoms of Makuria and Ethiopia including bishops, envoys and pilgrims, travelled to each other’s country and founded disporic communities abroad.

read more about it here: AFRICANS EXPLORING AFRICA CHAPTER 2;

Map by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith

An Archaeological Reconnaissance in the Horn: The British-Somali Expedition, 1975 by Neville Chittick pg 120-124, Early ports in the Horn of Africa by Neville Chittick pg 274-276

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 31, Imperialism Ancient and Modern: a study of British attitudes to the claims to Sovereignty t the Northern Somali coastline by David Hamilton pg 11

The Shaping of Somali Society by Lee V. Cassanelli pg 130)

Map by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith, additions taken from Luigi Bricchetti Robecchi’s 1893 map

Historical Aspects of Genealogies in Northern Somali Social Structure by I. M. Lewis pg 11

On the Neighbourhood of Bunder Marayah by S. B. Miles pg 69

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 49-50

The Promontory of Cape Guardafui by Giulio Baldacci pg 62

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 67-68

The Shaping of Somali Society by Lee V. Cassanelli pg 51, n24,

On the Neighbourhood of Bunder Marayah by S. B. Miles pg 61

Bollettino della Società geografica italiana By Società geografica italiana, pg 274-275.

The Promontory of Cape Guardafui by Giulio Baldacci 59-69)

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 47-49, 57-58

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 42, The Shaping of Somali Society by Lee V. Cassanelli pg 156-158

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 43-44.

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 44-45)

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 8, 50-52)

Map by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith

Transactions of the Linnean Society, Volume 27 By Linnean Society of London pg 133-134

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 35-36)

The Shaping of Somali Society by Lee V. Cassanelli pg 180

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 39, On the Neighbourhood of Bunder Marayah by S. B. Miles pg 61

The Promontory of Cape Guardafui by Giulio Baldacci pg 60-61

From Slaves to Coolies: Two Documents from the Nineteenth-Century Somali Coast by LE Kapteijns pg 2

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 48-52)

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 53-57)

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 57-59, 64-70)

The scramble in the Horn of Africa pg 239-244, From Slaves to Coolies: Two Documents from the Nineteenth-Century Somali Coast by LE Kapteijns pg 3-4

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 74-84)

The scramble in the Horn of Africa pg 236-238, 247

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith 82-85, The Arms Trade in East Africa in the Late Nineteenth Century pg 464

The Promontory of Cape Guardafui by Giulio Baldacci pg 71-72, Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith 86-91

Colonial Chaos in the Southern Red Sea by Nicholas W. Stephenson Smith pg 91-94)

The 'Mad Mullah' and Northern Somalia by Robert L. Hess pg 426-433

The Coinage of Ethiopia, Eritrea and Italian Somalia by Dennis Gill pg 324 The King's African Rifles - Volume 2 By Lieutenant-Colonel H. Moyse-Bartlett pg 450

why there is no one making a YouTube video about the history of this sultanate?

Thanks for sharing this article

interesting can we value the quality of life during those time periods