A history of the Massina empire (1818-1862)

the sucessor of Songhai

Buried in the pages of an old west African chronicle is a strange prophecy foretelling the emergence of a charismatic leader from the region of Massina in central Mali. According to the chronicle, the Songhai emperor Askiya Muhammad was transported into a spiritual realm where he was told that he would be suceeded as ‘Caliph’ of west Africa by one of his descendants named Ahmadu from Massina.

The empire of Massina emerged in 1818 and conquered most of the former territories of Songhai, ending the two centuries of political fragmentation that had followed Songhai's collapse. From its capital of Hamdullahi, the armies of Massina created a centralized government over a vast region extending from the ancient city of Jenne to Timbuktu, and nurtured a vibrant intellectual community whose scholars composed many writings including the chronicle containing the 'prophesy' related above.

This article explores the political history of the Massina empire, and its half a century long attempt to restore the power of Songhai.

Map of central Mali showing the extent of the Massina empire.1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

West Africa from the fall of Songhai to the rise of the revolution movements.

After the collapse of Songhai in 1591, the empire’s territories reverted to their pre-existing authorities as the remaining Moroccan soldiers (Arma) were confined to the cities of Djenne and Timbuktu where they established a weak city-state regime that was independent of Morocco. This state of political fragmentation continued until the early 18th century, when the Bambara empire expanded from its capital of Segu, and came to control much of the Niger river valley from Jenne to Timbuktu during the reign of N'golo Diara (1766-1795). At the turn of the 19th century, most of the region was under the Bambara empire’s suzeranity, but wasn’t fully centralized as local authorities were allowed to retain their pre-conquest status, these included the Arma of Jenne and Timbuktu, and the Fulbe/Fulani aristocracy of Massina.2

A reciprocal relationship existed between the (muslim) elites Djenné, the Arma, the Fulani, and their (non-Muslim) Bambara overlords, all of whom supported and legitimized each other to maintain the status quo. By the late 1810s the rising discontent over the political situation of Massina, characterized by the dominion of the powerful Bambara emperors and the local Fulani aristocracy, led an increasingly large number of followers to rally around Ahmadu Lobbo, a charismatic teacher who had spent part of his early life near Djenne where he had established a school.3

Djenne street scene, ca.1905/6

The antagonistic relationship between the elites of Djenne allied with the local Fulbe prince named Ardo Guidado against Ahmadu Lobbo and his followers eventually descended into open confrontation between the two groups that ended with prince Guidado's death. Ahmad Lobbo had by then written a polemic treatise titled Kitab al-Idtirar, in which he outlined his religious and political grivancies against the local authorities and against what he considered blameworthy practices of Jenne's scholary community.4

The political-religious movement of Ahmadu was part of a series of revolutions which emerged across west Africa’s political landscape in the 18th and 19th century. Prior to these revolutions, political power was in the hands of “warrior elites,” such as the Bambara of Segu, the Fulani aristocracy of Massina, and the Arma in Jenne and Timbuktu. while scholars/clerics occupied a high position in the region’s social hierachy, they were often barred from holding the highest political office. But as the power of the warrior-elites weakened, more assertive political theologies were popularized among the scholars who advocated political reform and made it permissible for their peers to hold the highest office. The scholars then seized power and established distinct forms of clerical rule in Futa Jallon (1725), Futa Toro (1776), Sokoto (1804) Massina (1818), and Tukulor (1861), where religious authorities become the government and attempt to exercise secular power with the weapons of religious ideology.5

Map of the 19th century ‘revolution’ states in west Africa. (map by LegendesCarto)

Having openly defied the authorities, Ahmad Lobbo's followers prepared for war. The local Fulbe chief Ardo Amadou, whose son (prince Guidado) had been killed by Lobbo's followers, successfully sought the support of the Bambara king Da Diarra (r. 1808-1827), as well as other Fulbe warriors, including Gelaajo, the chief of Kounari. Their combined army moved against Ahmad Lobbo and his followers, who had retreated to Noukouma. The battle between Lobbo's followers and the Bambara army occurred in March 1818, ended with the defeat of the Bambara who had attacked before the arrival of Arɗo Amadou and Gelaajo. Discouraged by this, the latter decided to abandon the war. By contrast, the ranks of Ahmad Lobbo swelled substantially after the victory at Noukouma, such that by mid-May 1818 Ahmad Lobbo emerged as the leader of a new state centered in Masina.6

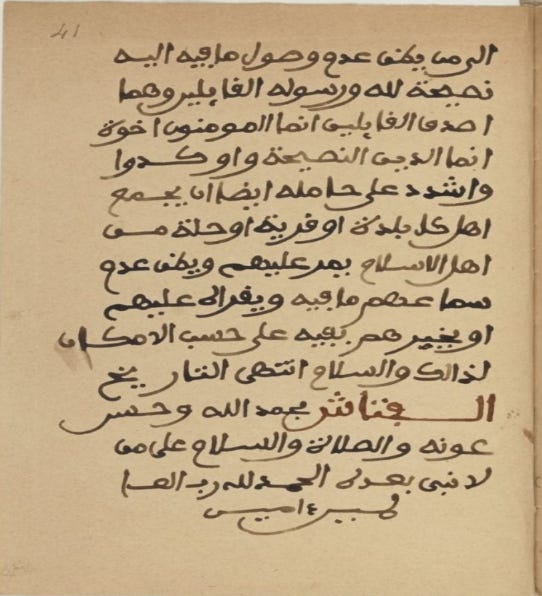

copy of the Kitab al-Idtirar by Amhadu Lobbo

Empire building and Government in Massina during the reign of Ahmadu I (1818-1845)

Like the Songhai armies centuries earlier, Lobbo's expansion was primarily conducted along the middle section of the Niger river between Djenne and Timbuktu, where he could combine overland and riverine warfare to capture the region's main cities. The city of Djenné was conquered twice, in 1819 and 1821 after some minimal resistance, and Ahmadu's son, named Ahmadu Cheikou was appointed its governor.7 By 1823, Ahmadu had defeated the armies of al-Husayn Koita at Fittuga, where a competing Fulbe movement had emerged, instigated by Sokoto’s rivary with Massina.8

Lobbo's armies also advanced northwards beginning in 1818, when they were initially defeated by a Tuareg force which controlled the area. But by 1825, Massina's army crushed the Tuareg forces at the battle of Ndukkuwal and incorporated the region from Timbuktu to the city of Gao into the Massina empire. An insurrection in Timbuktu was crushed in 1826 and Lobbo appointed Pasha Uthman al-rimi as governor, while San Shirfi became the imam of the Djinguereber Mosque.9

Internal challenges to Ahmadu's rule came primarily from the deposed Fulbe aristocracy such as Buubu Arɗo Galo of Dikko whose army was defeated in 1825. More threatening was the rebellion of Gelaajo of Kounari who controlled the region extending upto Goundaka in the bandiagara cliffs of Dogon country. After around seven years of intense fighting, Gelaajo was defeated and forced to flee to Sokoto.10

By the mid-1820s Ahmadu Lobbo had consolidated his control over most of the Middle section of the Niger river upto the Bandiagara cliffs, as well as the region extending northwards to Timbuktu. He established his capital at Hamdullahi, which was founded around 1821, and developed as the administrative center of the state. The walled city was divided into 18 quarters with a large central mosque next to Lobbo's palace, it also included a “parliament” building (called 'Hall of seven doors'), a court, a market, 600 schools and the residences of Massina's elite.11

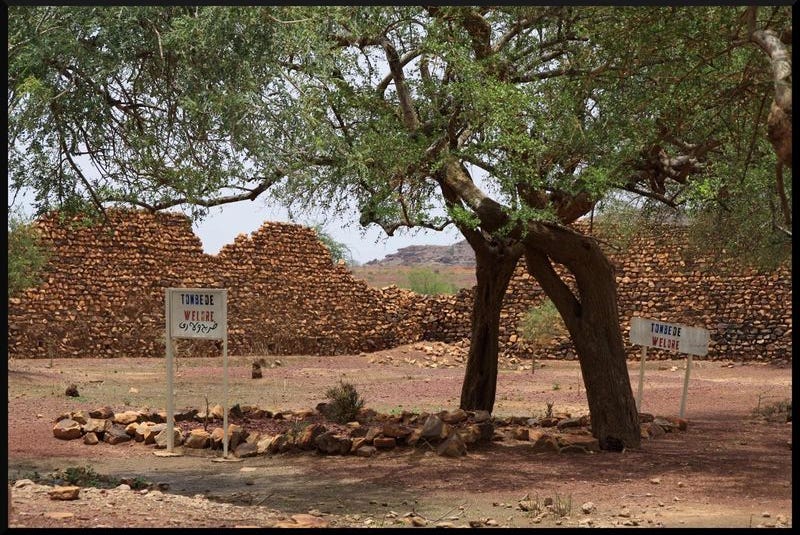

Ruins of Hamdullahi’s walls, the third photo includes the mausoleum of Ahmad I and Nuh al-Tahir, and a roofed structure where the ‘Hall of seven doors’ was located. 12

The administration of Massina was undertaken by the Great Council (batu mawɗo), an institution composed of 100 scholars that ruled the empire along with Ahmad Lobbo. This council was the official state assembly/parliament, and it was further dived into a 40-person house of permanent members headed by 2 scholars closest to Ahmad Lobbo, named Nuh al-Tahir and Hambarké Samatata. The council oversaw the governance of the empire's five major provinces and appointed provincial governors that were inturn assisted by their own smaller councils. The Great council made their rulings after consulting various (Maliki) legal and political texts used across the wider Muslim world including those written by west African scholars such as the Fodiyawa family of Sokoto. The council permanently resided in the capital, they regulary assembled in the parliament building, and also oversaw the policing of the capital.13

The administrative units of Massina were towns and villages called ngenndis, an conglomeration of these formed a canton (lefol leydi), which were inturn grouped together to form provinces (leyde). Each province was governed by an amir chosen by the Great Council, and was to be in charge of collecting taxes, overseeing the forces of each province. He was assisted by a Qadi appointed by the Great council to oversee provincial judicial matters that didn’t need to be sent to the Qadi in the capital.14

The intellectual tradition of Massina

The centralization of Massina was possible due to the substantial development of literacy in the region. literacy became the crucial tool for the development of an administrative apparatus based on orders that emanated from the capital and circulated through a capillary system of letters and dispatches to the different local administrative units. Members of the Great coucil were all highly accomplished scholars in their own right, and all provincial governors down to the lowest village were required to be literate.15

The scholary community of Massina produced many prominent figures and reinvigorated the region’s intellectual production as evidenced by the manuscript collections of Djenne. In Hamdullahi, most notable scholar from Massina was Nuh al-Tahir al-Fulani, one of the two leaders of the Great council, and the author of the famous west-African chronicle; the tarikh al-Fattash. Nuh al-Tahir was in charge of Hamdullahi's education system that managed the over 600 schools in the capital. Like most contemporary education systems in Muslim west-Africa, the schools of Hamdullahi were individualized, led by highly learned scholars who received authorization from Nuh al-Tahir to teach various subjects ranging from theology to grammar and the sciences.16

Nuh al-Tahir’s commentary on the Lamiyyat al-af‘al of Ibn Malik (d. 1274), and a short treatise titled Khasa’is al-Nabi, manuscripts found at the Ahmed Baba Institute of Higher Learning and Islamic Research, photos by M. Nobili.

Kitāb fī al-fiqh by Sīdī Abūbakr b. ‘Iyāḍ b. ‘Abd al-Jalīl al-Māsinī written in 1852, now at Djenné Manuscript Library.17

Intellectual disputes between Massina and Sokoto, and the creation of a west African chronicle

Both the political movement of Ahmadu, and the scholary community at Hamdullahi were in close contact with the Sokoto movement of Uthman Fodio in northern nigeria. Uthman Fodio had intended to expand his political influence over the middle Niger region, especially through his connection with the Kunta clerics and the scholars of Masina. Although Lobbo and Uthman never met, the influence of the latter's movement on the former can be gleaned from the correspondence exchanged between the Fodiyawa family of Uthman Fodio that closely corresponded with Ahmadu before and after Massina was founded.18

Ahmadu Lobbo reportedly sent a delegation to Uthman requesting the latter's support in his impending war against Segu, and the delegation came back with a flag representing his authority. But Lobbo's eventual military success and Uthman's death obfuscated any need for him to derive authority from Sokoto, and following the sucession disputes in Sokoto, Lobbo even made attempts to request that Sokoto submits to Massina prompting the then Sokoto leader Muhammad Bello (sucessor of Uthman Fodio) to inspire the abovementioned rival movement of al-Husayn Koita at Fittuga. The ideological and intellectual disputes between the two states eventually led to the creation of the Tarikh al-Fattash by Nuh al-Tahir, which contained sections which legitimated Lobbo's claim of being a Caliph and a sucessor of the Songhai emperor Askiya Muhammad.19

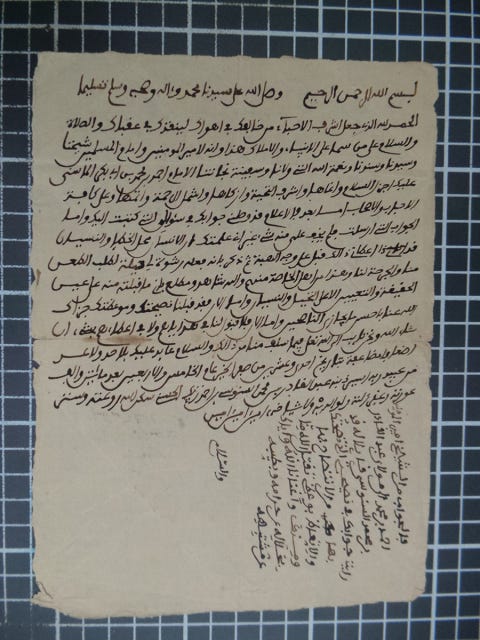

Letters by Sokoto ruler Muhammad Bello to the Massina ruler Ahmadu Lobbo on various questions of government including that of Massina’s allegiance to Sokoto, copy from 1840 now at National Archives Kaduna, Nigeria.20

Letter on the Appearance of the Twelfth Caliph by Nuh b. al-Tahir, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Ms. Arabe 6756. (Photo by M. Nobili)

Nuh al-Tahir’s Tarikh al-Fattash (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

The expansion of Massina under Amhadu I and the city of Timbuktu.

Massina owed much of its expansion to its armies, divided into the five major provinces of the empire. It was led by five generals (amiraabe), below whom were the pre-conquest war chiefs that had submited to Lobbo's rule. The soldiers were divided into infantry, cavalry and a river-navy, and their equipment, horses and rations were largely supplied by the state. Most of the soldiers were recruited by the individual war-chiefs, but a permanent cavalry corps was also maintained in garrisons on the outskirts of important cities such as Hamdullahi, Ténenkou, Dienné, and Timbuktu. Owing to the nature of its formation as an outgrowth of Lobbo's movement, the army's command structure was relatively less centralized with each unit fighting more or less independently under their leader albeit with the same goals.21

Massina's conflict with Segu continued on its western and southwestern fronts, with several battles fought around Djenne especially with the Bambara provinces of Sarro and Nyansanari. While Sarro largely remained at war with Massina, Nyansanari eventually surrendered to Massina and was incorporated into the state, with its leader being formally installed by Amhad Lobbo.22

Massina's expansion into the region between the Mali-Niger border and north-eastern Burkina Faso was more sucessful, and marked the southernmost limit of the empire, which it shared with the Sokoto empire. The various chiefdoms of the region, most notably Baraboullé and Djilgodji, were subsumed in the late 1820s after a serious of disastrous battles for the Massina army that ultimately ended when threats from the Yatenga kingdom forced the local chieftains to place themselves under Massina's protection. The conflict that emerged with the Bambara state of Kaarta, however, was more serious, with Massina's army suffering heavy casualties, especially in 1843–44. every attempt by to expand westward proved equally futile.23

After the first conquest of the north-eastern regions between Timbuktu and Gao in 1818-1826, Arma and the Tuareg who controlled the region rebelled several times, trying to escape the imposition of direct rule by Lobbo’s appointed governor Abd al-Qādir (who took over from Pasha Uthman al-rimi). This prompted Massina to firmly control the town in 1833 when a Fulbe governor was appointed that controlled the entire region upto Gao.24 A Tuareg force drove off the Massina garrison in 1840 but were in the following year defeated and expelled. The Tuareg then regrouped in 1842-1844 and managed to defeat the Massina forces and drive them from Timbuktu, but the city was later besieged by Massina and its inhabitants were starved into resubmitting to Massina's rule by 1846. Disputes between Massina and Timbuktu were often mediated by the Kunta scholary family led by Muhammad al-Kunti and his son al-Mukhtar al-Saghir .25

A letter from Mawlāy ‘Abd al-Qādir to Aḥmad Lobbo, which includes at the bottom the response of the caliph of Ḥamdallāhi. Ahmed Baba Institute of Higher Learning and Islamic Research, photo by Mohamed Diagayété

Folios from two letters sent by Muhammad al-Kunti addressed to Ahmadu Lobbo, advising the latter on good governance, written around 1818-1820, now at the Djenné Manuscript Library.26

The reign of Ahmadu II and the consolidation of Massina (1845-1853)

In the later years of Ahmadu's reign, the ageing ruler asked the Great Council to nominate his sucessor. The choice for the next ‘Caliph’ of Massina was narrowed down to two equally qualified candidates; an accomplished general named BaaLobbo, and the Caliph’s son, Ahmadu Cheikou who was a renowned scholar and administrator. The Great council picked Ahmadu Cheikou, who suceeded his father in March 1845 as Ahmadu II, and they chose BaaLobbo as the head of the military inorder to placate him and avoid a sucession dispute.27

Throughout his reign, Ahmadu II had to fight against the Tuaregs in the region of the Niger river’s bend near Timbuktu, as well as the Bambara empire of Segu which had resumed hostilities with Massina. However, none of the expansionist wars of Ahmadu’s reign were undertaken by Ahmadu II, who chose to retain the status quo especially between the Segu empire and the rebellious Tuareg-Kunta alliance near Timbuktu. This was partly done to prevent BaaLobbo from accumulating too much power, but it may have undermined Massina’s ability to project its power in the region. 28

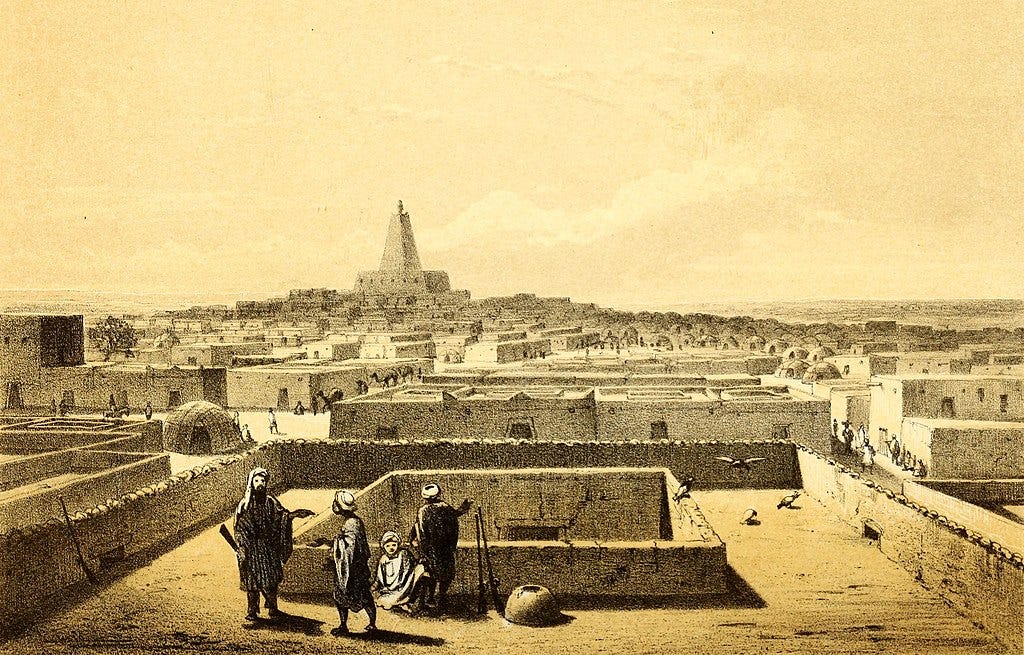

In 1847, Ahmadu II re-imposed the ruinous blockade of Timbuktu to weaken the Tuareg-Kunta alliance which had resumed its revolt against Massina soon after Ahmadu’s death. This blockade partially sucessful politically, as some of the Kunta allied with Massina against their peers led by Ahmad al-Bakkai al-Kunti who suceeded al-Mukhtar al-Saghir. al-Bakkai later travelled to Hamdullahi, negotiated a truce and Timbuktu resubmitted to Massina. But commercially, the blockade, which lasted nearly the entirety of Ahmadu II’s reign, ruined Timbuktu and drained the old city of its already declining fortunes.29 When the German explorer Heinrich Barth visisted Timbuktu and Gao around 1853-4, he provided a detailed description of both cities which were now long past their glory days, with Gao having been reduced to a village, while Timbuktu was a shadow of its former self.30

Illustration of Timbuktu by Heinrich Barth (1853)

The reign of Amhadu III and the collapse of Massina (1853-1862)

Ahmadu II died in 1853, and the problem of succession reemerged even more strongly than before. The best candidates to succeed him were, again, BaaLobbo and another of Ahmad Lobbo’s sons named Abdoulay, as well as Ahmad II’s son named Amadou Amadou. Feeling sidelined again, BaaLobbo quickly formed an alliance with Amadou Amadou who had been close to him and he considered easy to influence than Abdoullay. BaaLobbo then requested his allies on the Great council to consider his proposition, which was accepted by the majority and Amadou Amadou was installed as Ahmadu III.31

Ahmadu III inaugurated a less austere form of government in Massina that was harshly criticized by his contemporaries, and was immediately faced with rebellion from Abadulay which was only diffused after a lengthy seige of the capital and negotiation32. He also centralized all the power that had been divided between the caliph and the Great Council. In this way, he alienated the veteran leaders of the empire, transforming the Great Council into a mere mechanism for approving his decisions. Hence, most of its members abandoned both Ahmadu III and the Great Council shortly after his ascension. Ahmadu III lost the support of the Kunta when Ahmad al-Bakkai broke off his relationship with Hamdullahi. With little support from inside the capital or from Timbuktu, Ahmadu III initiated a policy of rapprochement with the Bambara rulers of Segou who became allies of Massina.33

This open alliance between a clerical Muslim state and a non-Muslim state was soon challenged by the Futanke movement of al-Hajj Umar Tal, a powerful cleric whose nascent empire of Tukulor had expanded from Futa jallon in Guinea to take over the kingdom of Kaarta in 1855 that had eluded Massina. The capture of Kaarta opened the road for the Tukulor armies to conquer Kaarta’s suzerain; the Segu empire, which threatened Massina despite both Umar and Amhadu III drawing legitimacy from the same political-religious teachings. Ahmadu III moved Massina’s armies to confront Tukulor’s forces in 1856 at Kasakary and in 1860 at Sansanding, all while exchanging letters justifying each other’s expansionism and challenging the legitimacy of either’s authority. Segu was eventually conquered by Umar in March 1861 forcing its ruler to flee to Hamdullahi for protection.34

After a series of diplomatic exchanges between Umar Tal and Ahmadu failed to secure the release of Segu’s deposed ruler, Umar decided to declare war against Massina. The Tukulor marched on Massina in April 1862 and the empire’s capital was occupied in the following month after Ahmadu III’s divided forces had treacherously abandoned him and the beleaguered leader had died from wounds sustained during the battle. The ever ambitious BaaLobbo had surrendered to Umar Tal hoping the latter would retain him as ruler of Hamdullahi, but Umar instead appointed his son (also called Ahmadu). Enraged by Umar’s duplicity, BaaLobbo raised a rebellion, laid siege on Hamdullahi, and forced Umar to flee to his death in 1864.35

The capital of Massina would be reduced to ruins after several battles as it switched between Umar’s sucessors and the “rebels”. The empire of Massina was erased from west-Africa’s political landscape, ending the nearly half a century long experiment to restore Songhai.

When Europe was engulfed in one of the history’s deadliest conflicts in the early 17th century, the African kingdoms of Kongo and Ndongo took advantage of the European rivaries to settle their own feud with the Portuguese colonialists in Angola. Kongo’s envoys traveled to the Netherlands, forged military alliances with the Dutch and halted Portugal’s colonial advance. Read more about this in my recent Patreon post:

Map by M. Ly-Tall

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 177-178)

UNESCO general history of Africa volume VI pg 601-603

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 137-141, L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 26-27)

Beyond jihad: The pacifist tradition in West African Islam by L. Sanneh

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 10-11)

L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ 199-203)

UNESCO general history of Africa volume VI pg 603

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 155-160, 170-173 )

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 149-151, L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 146-163)

L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 46-51)

L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 64-68, 52)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 211-212)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 213, L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 68, 88

L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 51, 70-71)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 132-133, 135-137)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 182-200, Frontier Disputes and Problems of Legitimation: Sokoto-Masina Relations 1817-1837 by C. C. Stewart pg 499-500

L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 75-88)

L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 184-191, 206-209)

L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 214-220

L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 269, A note on Mawlāy ‘Abd al-Qādir b. Muḥammad al-Sanūsī and his relationship with the Caliphate of Ḥamdallāhi by Mohamed Diagayété

Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa by Heinrich Barth vol 4 pg 433-436, Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 160-176

L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 312-314, 326

UNESCO general history of Africa volume VI pg 608-609

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 176-181

Travels and discoveries in North and Central Africa by Heinrich Barth vol 5 pg 1-94, pg 215-220

L'empire peul du Macina by Amadou Hampâté Bâ pg 360-361

UNESCO general history of Africa volume VI pg 610

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by Mauro Nobili pg 233)

UNESCO general history of Africa volume VI pg 613-618, In the Path of Allah: The Passion of Al-Hajj ʻUmar by John Ralph Willis pg 171-184

In the Path of Allah: The Passion of Al-Hajj ʻUmar by John Ralph Willis pg 185-188, 218-222

I know you work very hard to produce your African history posts. And I’m sorry it doesn’t seem like many people read/rate your articles.

Honestly speaking and from a Black American point of view, I am very interested in the topic on your least favorite subject: African Slavery and the Diaspora of Africans around the globe.

What we don’t know, hear or understand about the slavery of our ancestors is

1. Why us and who are we?

2. What do today’s Africans know about this history and how do they feel about their slave trading ancestors? How do they feel about us?

3. How can we, today’s Black Americans and Africans, build or mend our relationship?

4. How can we forgive and forget the past and try to move forward in some kind of partnership of kinship?

My husband and I plan to visit a couple of African countries in the next several years. We want to walk on the land of our forefathers and feel the essence of our ancestors.

Thank you for reading my message.

Anita

Atlanta, Georgia

This is very helpful I would be reading more of your articles