A history of the west African diaspora in Arabia and Jerusalem before 1900

The legacy of west African travel to Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem.

Tucked along the western edges of the world's most contested religious site, are the residencies of west Africa's oldest diaspora in the eastern Mediterranean. The west-African quarter of Jerusalem's old city is one of three major diasporic communities established by west African Muslims outside Africa, the other two are found in the cities of Mecca and Medina

The history of the West African diaspora in Arabia and Jerusalem is a fascinating and often overlooked aspect of the African diaspora. For centuries, West Africans have traveled to these regions as scholars and pilgrims, leaving an indelible mark on their intellectual and religious traditions of the middle east.

This article explores the history of the West African diaspora in Arabia and Jerusalem, tracing the growth of the diaspora from Egypt to Arabia and Jerusalem, and highlighting their intellectual and cultural contributions.

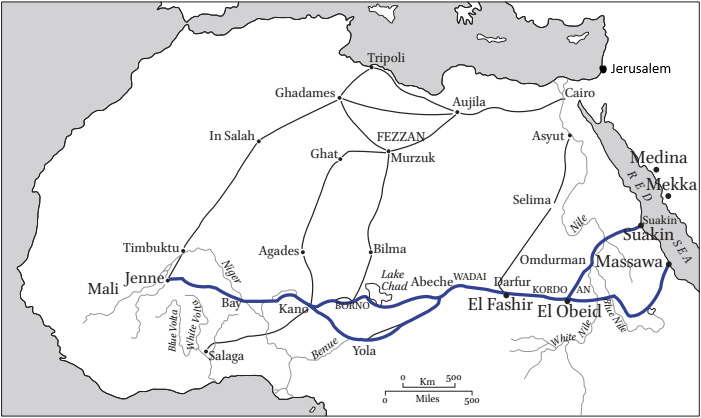

Map showing the route taken by west African pilgrims to Arabia and Jerusalem

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Foundations of a west African diaspora: the Takruri residents of Cairo

Scholars, pilgrims and travelers from west Africa had been present in Arabia and Palestine since the early second millennium. Initially, the west African diaspora only extended into Egypt, where the earliest documented west African Muslim dispora resided.

The enigmatic Cairo resident named al-Shaikh Abu Muhammad Yusuf Abdallah al-Takruri lived in Egypt during the 10th century. After he died, a mausoleum and mosque was built over his grave, and later rebuilt around 1342. His nisba of "al-Takruri" was evidently derived from the medieval west African kingdom of Takrur which was widely known in the Islamic world beginning in the 11th century and would become the main ethnonym for west African pilgrims travelling to the Holy lands.1

By the 14th century, the west African diaspora in Cairo had grown significantly especially after several pilgrimages had been undertaken that included reigning west African kings. The west African community in Egypt (or more likely the ruler of Bornu) commisioned the construction of the Madrasat ibn Rashiq around 1242 to house pilgrims from Bornu2. The community must have been relatively large, given the presence of a west African scholar named Al-Haj Yunis who was the interpreter of the Takrur in Egypt and provided the information on west African history written by Ibn Khaldun.3

A particulary important locus for the west African diaspora in Egypt was the university of al-Azhar. The first residence for West African students and pilgrims was established in Al-Azhar during the mid-13th century for Bornu’s students and pilgrims (Riwāq al-Burnīya). By the 18th century, 3 of the 25 residences of Al-Azhar hosted students from West Africa. These included the abovementioned Bornu residence, the Riwāq Dakārnah Sāliḥ for students from Kanem, and the Riwāq al-Dakārinah for students from; Takrūr (ie: all kingdoms west of the Niger river), Sinnār (Funj kingdom in Sudan), and Darfūr.4

Among the most prominent west African scholars resident in Egypt was Muḥammad al-Kashnāwī, a scholar from the Hausa city-state of Katsina in northern Nigeria. He boasted a comprehensive scholarly training before leaving Katsina around 1730, having been a student of the Bornu scholar Muḥammad al-Walī al-Burnāwī. al-Kashnāwī became well known in Egypt especially as the author of an important treatise on the esoteric sciences and as the teacher of Ḥasan al-Jabartī, the father of the famous Egyptian historian ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Jabartī.5

Another prominent west African resident in Cairo was Shaykh al-Barnāwī (d. 1824) from Bornu and was one of the important members of the Khalwati sufi order. He thus appears in the biographies of prominent Egyptian and Moroccan scholars of the same order as their teacher including ʿAlī al-Zubādī (d. 1750) and ʿAbd al-Wahhāb al-Tāzī (d. 1791).6

Many west African scholars are known to have resided permanently in Cairo. Archives from Cairo include lists of properties and possessions owned by west African Muslims on their way to the Hijaz. These include Hajj Ali al-Takruri al-Wangari who left 200 mithqals of gold and camels in 1562, and another document from 1651 listing nearly 500 mithqals of gold, cloth and several personal effects belonging to atleast 6 west Africans, 4 of whom had the nisba “al-Takruri”.7 The Cairo disporic community would doubtlessly have enabled the establishment of smaller disporic communities in the 'Holy cities' of Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem

students at the Al-azhar university in Cairo, early 20th century postcard.

The west African diaspora in Mecca and Medina.

The Holiest city of Islam was the ultimate destination for the pilgrimage made by thousands of west Africans for centuries, yet despite its importance, few appear to have resided there permanently. There’s atleast one reference to a 17th century Bornu ruler purchasing houses in Cairo, Medina and Mecca in order to lodge pilgrims; he also bought stores to meet the costs of the houses.8

Some of the more detailed descriptions of west Africans in Mecca are derived from 19th century accounts. In 1815, the traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt noted the presence of “Takruri” "Negro Hadjis" residing in Messfale (misfala quarter of mecca) and at Suq al-saghir (about 200m from the Kaaba). But all appear to have been temporary residents, some of whom were engaged in trade to cover the cost of their journey back to west Africa.9

The account of Richard Burton in 1855 further corroborates this. He describes the city’s "heterogeneous mass of pilgrims" as including the 'Takrouri' "and others from Bornou, the Sudan (Darfur and Funj), Ghdamah near the Niger and Jabarti from the Habash".10

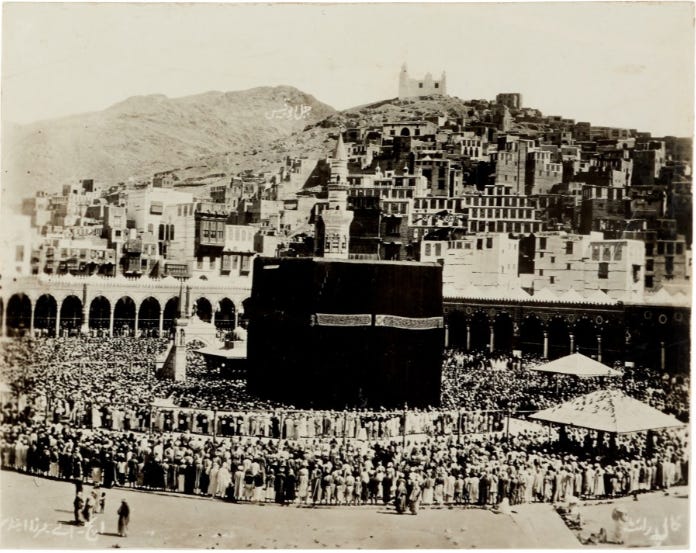

view of the Kaaba at Mecca, early 20th century

In contrast to Mecca, west Africans had a significant presence in Medina. Pious west Africans attimes took up residence in the city towards the end of their lives, to spend their last days, and then to be buried 'close' to the Prophet's grave. For example, the west African scholar Abu Bakr from the city of Biru (walata) travelled with his family to Medina on his second pilgrimage, and settled in the city where he'd later be buried in 1583.11

Another west African known to have resided in Medina was the 18th century scholar and merchant named Muhammad al-Kànimì, the father of the better known scholar Shehu al-Kanimi who ruled Bornu. Originally from Kanem, Muhammad moved to the Fezzan, before retiring in medina where he later died during the late 18th century.12

Given the importance of Medina to West African pilgrims, rulers such as the Songhai emperor Askiya Muhammad made charitable donations at several sacred places in the Hijaz, and purchased gardens in Medina which he turned into an endowment for the people of Takrur. Writing in 1655, the Timbuktu chronicler al-Sa'di indicates that the Askiya’s gardens were still in use at the time, mentioning that "these gardens are well known there".13 similarly, the Bornu ruler Mai Idris Alooma purchased a garden in Medina during the 16th century where he installed his followers.14

However, the experience of some 18th century west African scholars indicates that the gardens may have been abandoned at the time. The shinqit-born scholar Abd al-Rashid Al-Shinqiti, who was a resident of Medina, went to great lengths to receive stipends from the foundations of Maghribis (mostly Moroccans) in Medina, and despite obtaining support from Egyptian and Moroccan scholars in 1785, he was still denied the stipends. His contemporary named Abd al-Ramàn al-Shinqiti (d. 1767) who also resided in the city lived in household of a non-west African —in the Zawiya of the Sammàniyya founder Muhammad as-Samman.15

There are a number of west African scholars who gained prominence in Medina besides the above mentioned scholars from Shinqit (Chinguetti). The latter city was itself a major departure point for many west African pilgrim caravans heading to Mecca during the 18th and 19th centuries, among these pilgrims was the scholar Ṣāliḥ al-Fullānī. Born in Futa Jallon (modern-day Guinea), al-Fullani came to reside in Medina with a wide reputation for Islamic scholarship.16

al-Fullani was educated locally in Futa Jallon, Adrar and Timbuktu before proceeding to Marrakesh, Tunis and Cairo, and arriving at Medina in 1773. While in medina, he studied many subjects, and after he had "read all the major Islamic writings of his time", he became a teacher. His students included the qadi of mecca Abd al-Ḥāfiẓ al-ʿUjaymī (d. 1820) as well as Muḥammad ʿAbīd al-Sindī (d.1841) from sindh in Pakistan. His notable African students included Muḥammad al-Ḥāfiẓ al-Shinqītī (d. 1830), as well as the Moroccan scholar Ḥamdūn b. al-Ḥājj (d. 1857).17

Such was al-Fullani's influence that the Indian scholar, Muḥammad ʿAẓīmābādī (d. 1905), referred to him as the scholarly renewer (mujaddid) of his age, and his writings inspired India’s Ahl al-Ḥadīth movement.18

See this Patreon post on al-Fullani's influence in India:

Ruins of Chinguetti, southern Mauritania

The west African diaspora in Jerusalem

During the Umayyad period when the Hajj tradition was firmly established, the city of Jerusalem was transformed into the 3rd holy city of Islam after the construction of the Dome of the Rock on the ruins of an old temple. This construction followed an Islamic tradition about the prophet ascending to heaven from the Dome. Jerusalem was therefore an important center of pilgrimage for all Muslims alongside other Abrahamic religions.

West African Muslims likely travelled to Jerusalem early since the emergence of their pilgrimage tradition, but evidence for this is limited. The earliest reference to a west African Muslim community in Jerusalem likely dates to the Mamluk era when a Jerusalem waqf was given to a resident West African community, granting them a historic role as one of the guardians of the Al-Aqsa mosque.19

Jerusalem's west African Muslim community (called the 'Tukarina') grew significantly during the Ottoman era especially around the al-Aqsa mosque’s council gate (Bab al-Nazir). Around the early 16th century, the Ribat ‘Ala’ al-Din and the Ribat al-Mansuri, which were originally built in the 13th century as hostels for pilgrims, were officially transformed into permanent residencies for west African pilgrims.20

The Tukarina found jobs as the official guardians for the colleges and residencies around the entrance of al-Aqsa. Such was the Tukarina's control of the gates to prevent non-Muslims from entering that they were detained in 1855 by the local ottoman governor of Jerusalem to prevent them from denying entrance to the then Belgian prince Leopold II —the first Christian ruler since the Crusades to be allowed into the Dome of the Rock, prior to his infamous colonization of Congo.21

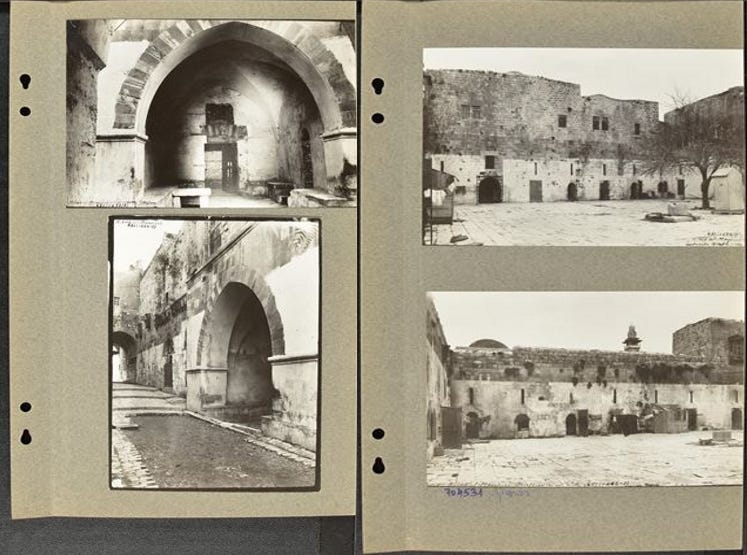

exterior and interior of the Ribat al Mansuri, early 20th century, The Israel Antiquities Authority22

Arguably the most notable west-African resident in Jerusalem (albeit briefly) was the Tukulor empire founder Umar Tal. Al-Hajj Tal left his homeland of Futa-Toro in 1826, arrived in Mecca in 1828 and stayed there for several years. He later traveled to Jerusalem and after several weeks departed for Cairo, before traveling back to west Africa. While in Jerusalem, Umar’s reputation for piety and learning were recognized, he led the prayer in the Dome of the Rock and treated a son of Ibrahim Pasha.23

These two ribats of ‘Ala’ al-Din and Ribat al-Mansuri now comprise the largest "African quarter" in Jerusalem (al-jaliyya al-Afriqiyya) adjacent to the gates of the famous Al Aqsa Mosque. After the arrival of more African Muslims from colonial west africa during the early 20th century, the diasporic community now has a population of about 500 (but far more Africans live outside the quarter itself).24 While relatively small compared to the modern dispora of west Africans in mecca and medina, its position in front of one of the word's most contested sites has given the community a significant place in politics of the Old city.

Hall of the Ribat of al-Mansur Qalawun, photo by ‘Discover Islamic Art’

Conclusion: west africa’s diaspora in world history

Examining the significance of the West African diaspora in Arabia and Jerusalem, allows us to gain a deeper understanding of the complex historical and cultural connections that exist between Africa and the Middle East. From the writings of resident west African scholars in Medina and Cairo, to the cultural roles of west Africans in Jerusalem, the region’s African communities highlights the diversity of the Muslim world, and the many ways in which it has been shaped by different cultural influences over time.

And as a testament to the often overlooked presence of the African diaspora in the eastern Mediterranean, Jerusalem’s historical African quarters for west Africans and Ethiopians are located within about 200 meters of each other. This underscores the cosmopolitan nature of African communities outside the continent as active agents in world history.

Map showing the west-African and Ethiopian quarters in the Old city.25

on AFRICANS DISCOVERING AFRICA: Far from existing in autarkic isolation, African societies were in close contact thanks to the activities of African travelers. These African explorers of Africa were agents of intra-continental discovery centuries before post-colonial Pan-Africanists

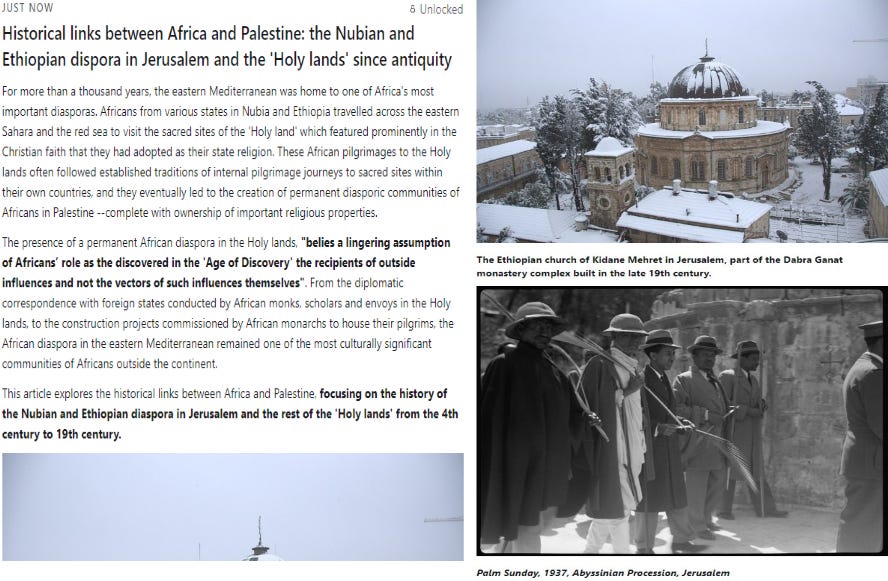

On the Nubian and Ethiopian diaspora in Jerusalem:

If you like this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

Takrur the History of a Name by 'Umar Al-Naqar pg 365-370)

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 223, 249

Takrur the History of a Name by 'Umar Al-Naqar pg 370)

Islamic Scholarship in Africa by Ousmane Oumar Kane pg 8)

The African Roots of a Global Eighteenth-Century Islamic Scholarly Renewal by Zachary Wright pg 31)

The African Roots of a Global Eighteenth-Century Islamic Scholarly Renewal by Zachary Wright pg 32)

Trade between Egypt and bilad al-Takrur in the eighteenth century by Terence Walz pg 27-28

Trade between Egypt and bilad al-Takrur in the eighteenth century by Terence Walz pg 26

Travels in Arabia by John Lewis Burckhardt, 24, 85, 203-204, The Hajj: The Muslim Pilgrimage to Mecca and the Holy Places By F. E. Peters pg 96-98

Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah, Volume 1 By Richard F. Burton pg 177

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 45, 59)

The Transmission of Learning in Islamic Africa by Scott Steven Reese pg 141)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 105)

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 250

The Transmission of Learning in Islamic Africa by Scott Steven Reese pg 129-130, 148)

The Transmission of Learning in Islamic Africa by Scott Steven Reese pg 43, 132-133)

West African ʿulamāʾ and Salafism in Mecca and Medina by Chanfi Ahmed pg 93-96)

Islamic Scholarship in Africa by Ousmane Oumar Kane pg 33

Black African Muslim in the Jewish State by William F. S. Miles pg 39-40,

Mamluk Jerusalem: An Architectural Study by Michael Hamilton Burgoyne pg 119

Mamluk Jerusalem: An Architectural Study by Michael Hamilton Burgoyne pg 121, , Great Leaders, Great Tyrants? by Arnold Blumberg pg 160, Medievalism in Nineteenth-Century Belgium by Simon John pg 144.

From West Africa to Mecca and Jerusalem by Irit Back pg 12-14, In the Path of Allah: 'Umar, An Essay into the Nature of Charisma in Islam' By John Ralph Willis pg 87

The Dom and the African Palestinians by Matthew Teller pg 95-99, in ‘Jerusalem Quarterly, 2022, Issue 89’, Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem by Ali Qleibo pg 64-67)

adapted from: The Growth of Jerusalem in the Nineteenth Century by Y. Ben-Arieh, pg 256

This was a wonderful topic I knew that there was an historical presence of West Africans in places such as Jerusalem and Mecca and Medina and West Asia however the extent and exact nature of such is something I didn't realize. This was very informative and I appreciate the insights. Btw have you any info on West African or African presence in general in places such as Baghdad and or Damascus as well?