A history of Zanzibar before the Omanis (600-1873)

Journal of African cities chapter 7

For most of the 19th century, the western Indian ocean was controlled by a vast commercial empire whose capital was on the island of Zanzibar. The history of Zanzibar is often introduced with the shifting of the Omani capital from Muscat to Stone-town during the 1840s, disregarding most of its earlier history save for a brief focus on the Zanj revolt.

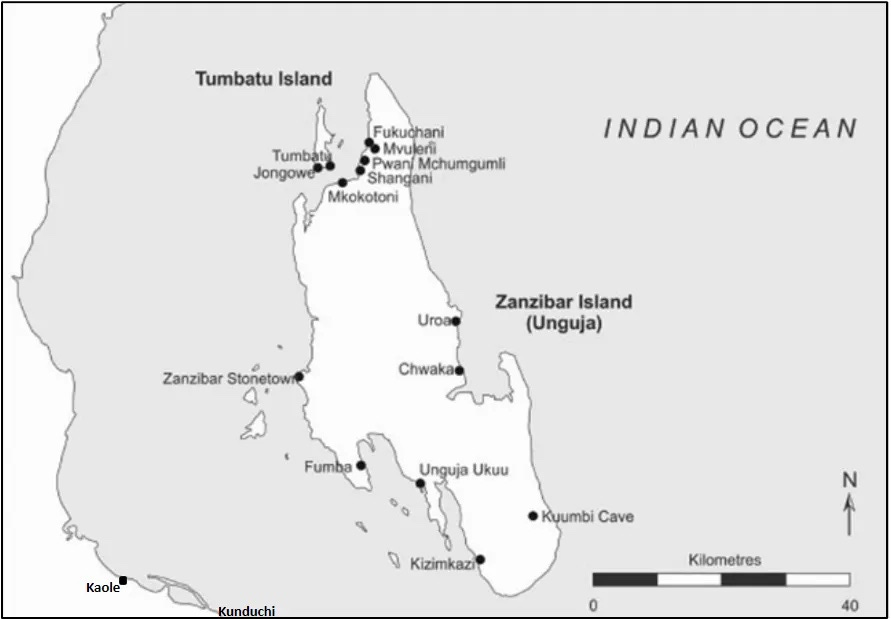

Zanzibar was for centuries home to some of Africa's most dynamic urban societies, long before it became the commercial emporium of the 19th century. With over a dozen historical cities and towns, the island played a central role in the political history of east Africa —from sending envoys as far as China, to influencing the activities of foreign powers on the Swahili coast.

This article explores the history of Zanzibar, beginning with the island's settlement during late antiquity to the formal end of local autonomy in 1873.

Map of the east African coast showing the location of Zanzibar island1

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Zanzibar in the 1st Millennium: From Unguja to China

The island of Zanzibar (Unguja) is the largest in the Zanzibar Archipelago, a group of islands that includes Pemba, Mafia and several dozen smaller islands. Zanzibar has a long but fragmentary record of human settlement going back 20,000 years, as shown by recent excavations at Kuumbi Cave. But it wasn’t until the turn of the common era that permanent settlements were established by sections of agro pastoral populations that were part of the wider expansion of Bantu-speakers.2

According to the Perilus, a 1st-century text on the Indian ocean world, the local populations of the east African island of Menouthias (identified as Pemba, Zanzibar or Mafia) used sewn watercraft as well as dugout canoes to travel along the coast, and fished using basket traps. There's unfortunately little archeological evidence for such communities on Zanzibar itself during the 1st century, as occupation is only firmly dated to around the 6th century.3

Between the late 5th and early 6th century, Zanzibar, like most of the East African coast, was home to communities of ironworking agriculturalists speaking Swahili and other Northeast-Coast Bantu languages4. Two early sites at Fukuchani and Unguja Ukuu represent the earliest evidence for complex settlement on Zanzibar island. The discovery of imported roman wares and south-asian glass indicates that the island’s population participated in long distance trade with the Indian ocean world, albeit on a modest level .5

Like most of the early Swahili settlements during the mid-1st millennium, the communities at Unguja Ukuu and Fukuchani constituted small villages of daub houses whose occupants used local pottery (Tana and Kwale wares). Subsistence was based on agriculture (sorghum and finger millet), fishing and a few domesticates. Craft activities included shell bead-making and iron-working, as well as reworking of glass. By the late 1st millennium, the Zanzibar sites of Unguja Ukuu, Fukuchani, Mkokotoni, Fumba and Kizimkazi were able to exploit their position to become trade entrepôts.6

Kizimkazi mosque, early 20th century photo. An inscription decorating the qiblah wall of the mosque was dated to 1107.

Map of Zanzibar island showing some of the towns mentioned in this text.

The town of Unguja Ukuu, which covered over 16ha in the 9th century, became the largest settlement on Zanzibar island during this period, and one of the largest along the Swahili coast. The rapid growth of Unguja Ukuu can be mapped through massive quantities of imported material derived from trade. While Ugunja's material culture remained predominantly local in origin, significant amounts of imported wares (about 9%) appear in Unguja's assemblages beginning in the 6th century, that include Indian and Persian wares, as well as Tang-dynasty stoneware from China, Byzantine glass vessels and glass beads from south Asia.7

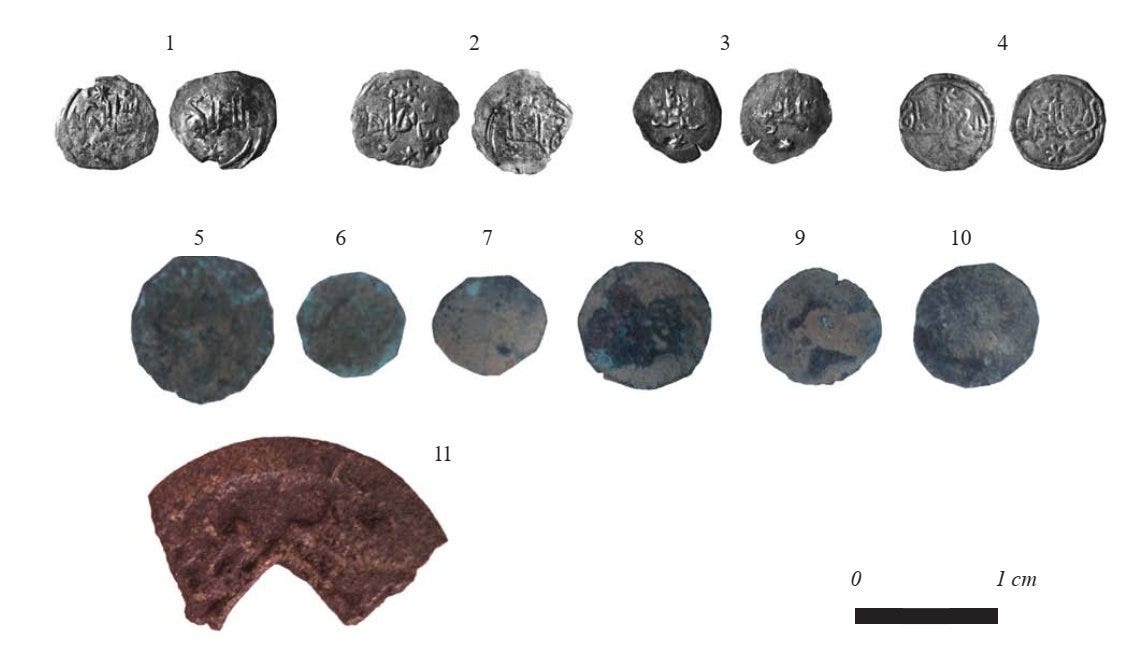

The imports at Unguja would have been derived from its external trade with the African mainland and Indian ocean world, which is also evidenced by its local population's gradual adoption of Islam and their construction of a small mosque around 900. Additionally, copper and silver coins were minted locally by two named rulers during the 11th century, and the foreign coins from the Abbasids and Song-dynasty China were used.8 A similar but better-preserved mosque was built at Kizimkazi around 1107. it features early Swahili construction styles where rectilinear timber mosques with rectangular prayer halls were translated into coral-stone structures.9

Unguja is one of the earliest Swahili towns mentioned in external accounts, besides its identification as Lunjuya by al-Jāḥiẓ (d. 868), its also mentioned in the Arabic Book of Curiosities ca.1020 which contains a map showing the coasts of the Indian Ocean from China to eastern Africa where its included as ‘Unjuwa’ alongside ‘Qanbalu’ (Pemba island). 10 The elites of Unguja were also involved in long distance maritime travel. During Song dynasty china, the african envoy named Zengjiani who came from Zanzibar (rendered Cengtan in Chinese = Zangistân) and reached Guangzhou in 1071 and 1083, is likely to have come from Unguja.11

Zengjiani gave a detailed description of his home country including his ruler's dynasty that had been in power for 5 centuries, and the use of copper coins for trade12. Despite probably being embellished, this envoy's story indicates that his ruler's dynasty was about as old as Ugunja and may reflect the town's possibly hegemonic relationship with neighboring settlements. Historically, most Swahili city-states developed as confederations which included a major cultural and trading center like Unguja, surrounded by various less consequential settlements located at a distance on the mainland or on other parts of the island.13

ruins of a late medieval structure at Unguja Ukuu14

Unguja Ukuu, Local silver coins (1-11) and one Chinese bronze coin (11) Among the local coins are those belonging to an Unguja ruler named Muhammad bn Is-haq (1-3) dated to the 11th century, one belonging to an Unguja ruler named Bahram bn Ali (5) also dated to the 11th century, and uninscribed local pieces (5-10) also dated to the same period, the chinese coin is from the mid-12th century.15

Unguja Ukuu, the Indian ocean world and the Zanj episode

Given the Zanzibar island's central location between the early mainland Swahili settlements such as Kunduchi and Kaole, and the offshore islands such as Pemba, the town of Unguja would have controlled some of the segmented trade between the mainland, the coast and the Indian ocean world. Most of this trade would have been locally confined given the paucity of imported material and the modest size of the settlements, but some would have involved exports. Exported products likely included typical products attested in later accounts such as ivory, mangrove, iron, and possibly captives, although no contemporary account mentions these coming from Zanzibar.16

Despite Unguja's relatively small size and its modest external trade, the town's importance had been exaggerated by some medievalists as the possible origin of the so-called Zanj slaves who led a revolt in Abassid Iraq from 869 and 883. This has however been challenged in recent scholarship, showing that actual Zanj slaves were a minority in the revolt. Not only because the very ambiguous ethnonym of 'Zanj' was applied to a wide variety of people from africa who were in Iraq, but also because most rebel leaders of the Zanj revolt were free and their forces included many non-africans.17

Additionally, there's also little mention of slave trade from the Swahili coast before 950 in accounts written during the period just after the revolt18 (the account of al-Masudi, who visited Pemba in 916, only mentions ivory trade). There's also little mention of slave trade in the period between 960 and the Portuguese arrival of 1499; (the secondary account of Ibn Shahriyar in 945 which does mention an incident of slave capture was copied by later scholars, but Ibn Batutta's first hand account in the 1330s makes no mention of the trade.19)

Furthermore, the moderate volumes from the east African coast between the 15th and 18th century were derived from secondary trade in Madagascar prior to the trade's expansion in the 19th century. The Swahili cities were too military weak to obtain captives from war, and their external trade was too dependent on transshipment from other ports (their "exports" were mostly re-exports).20

Zanzibar between the 12th and 15th century: The rise of Tumbatu

Unguja Ukuu gradually declined after 1100 when its last ruler is attested21. During this period, the island of Zanzibar appears to have gone through a period of settlement reorganization coinciding with the expansion of other Swahili city-states along the coast, and the emergence of new settlements on Zanzibar. This includes the town of Tumbatu, which emerged on the small island of Tumbatu around 1100 and remained the largest on the Island until the 14th century,22 and other settlements, e.g at stone town.23

By the 13th century, Tumbatu was a relatively large city of large coral houses with associated kiosks and atleast three monumental mosques. The rulers at Tumbatu struck coins of silver and copper between the 12th and 14th century, which share stylistic similarities with those later attested at Kilwa.24 The mosque at Tumbatu followed the design established at Unguja and kizimkazi with a few additions including the use of floriate Kufic and a trefoil arch. The rise of Tumbatu benefited other towns such as Shangani and Fukuchani which all show significant settlement expansion during the 13th century.25

Tumbatu declined after 1350 following a sudden and violent abandonment with signs of burning and deliberate destruction of houses and its mosques, and its elites most likely moved to Kilwa.26 The famous globetrotter Ibn Battua also failed to mention Tumbatu (or even Zanzibar island) during his visit to the Swahili coast, in stark contrast to the city’s prominence one century prior. However, settlements on the island of Zanzibar itself would continue to flourish especially at Shangani and Fukuchani. The discovery of both local and foreign coins at both sites, as well as the continued importation of Islamic glazed wares and Chinese celadon, demonstrates the continuity of Zanzibar's commercial significance.27

Friday mosque at Tumbatu

Zanzibar from the 15th to the 18th century: The Portuguese era

More settlements emerged on Zanzibar island at Uroa and Chwaka around the late 14th/early 15th century, and the ruined town of Unguja Ukuu was reoccupied prior to the Portuguese arrival in the 1480s. Like many of its Swahili peers, Zanzibar's encounter with the Portuguese was initially antagonistic. Unguja was sacked by the Portuguese in 1499, with the reported deaths of several hundred and the capture of 4 local ships from its harbour.28 And in 1503 20 Swahili vessels loaded with food (cereal) were captured by the Portuguese off the coast of Zanzibar.29

However, some of the states on Zanzibar (presumably those on the western coast of the island) whose political interests were constrained by Mombasa's hegemony would ally with the Portuguese against their old foe. In 1523, emissaries from Zanzibar requested and obtained Portuguese military assistance in re-taking the Quirimbas Islands (in northern Mozambique) that were under Mombasa's suzerainty. By 1528, Zanzibar's elites welcomed Portuguese fleet and offered it provisions in its fight against Mombasa. And by 1571, a ‘king’ from Zanzibar also obtained Portuguese military assistance in putting down a rebellious mainland town.30

Like other Swahili city-states, the political system on Zanzibar island would have been directed by an assembly of representatives of patrician lineage groups, and an elected head of government. The titles of "King" and "Queen" used in Portuguese accounts for the leading elites of Zanzibar were therefore not accurate descriptors of their political power.

The pacification of Mombasa in 1589 was followed by the establishment of a Portuguese colonial administration along the Swahili coast that lasted until 1698, within which Zanzibar was included. The colonial authority was represented by the ‘Fort Jesus' at Mombasa, a few garrisons at Malindi, and a few factors in various cities. It was relatively weak, the token annual tribute was rarely submitted, and rebellions marked most of its history. However, the pre-existing exchanges on Zanzibar -- especially its Ivory, cloth and timber trade-- were further expanded by the presence of Portuguese traders.31

The western towns of Shangani and Forodhani emerged around the 16th century, and became the nucleus of Mji Mkongwe (Old Town), later known as 'stone town' . The residence of a Portuguese factor was built near Forodhani in 1528, rebuilt in 1571, and was noted there by an English vessel in 1591. An Augustinian mission church was also built around 1612 supported by a small Portuguese community. 32

But the northern and southern parts of the Island appear to have remained out of reach for the weak colonial administration at stone-town. The settlements of Fukuchani and Mvuleni which are dated to the 16th century feature large fortified houses of local construction that were initially thought to be linked to Portuguese agricultural activities. But given the complete absence of the sites in Portuguese accounts and their lack of any Portuguese material, both settlements are largely seen as home to local communities mostly independent of Portuguese control.33

ruined house at Fukuchani

The growing resistance against the Portuguese presence especially by the northern Swahili city of Pate led to its elite to invite the Alawi family of Hadrami sharifs. Swahili patricians seeking to elevate the prestige of their lineages entered into matrimonial alliances with some of the Alawis, creating new dynastic clans.34In stone-town, the dynastic Mwinyi Mkuu lineage entered matrimonial alliances with the Sayyid Alawi with Hadrami and Pate origins. These Zanzibari elites therefore adopted the nisba of Alawi, but the Alawi themselves had little political influence, as shown by the continued presence of women sovereigns in Zanzibar.35

By 1650 stone-town’s queen Mwana Mwema who’d been allied with the Portuguese joined other Swahili elites in rebellion by forming alliances with the Ya'rubid dynasty of Oman. In 1651, Mwana Mwema invited a Ya'rubid fleet which killed and captured 50-60 Portuguese resident on the island, and she called for further reinforcements by sending two of her ships. However, the reinforcements didn’t arrive, and the elites of Kaole —stone-town's rival city on the mainland— would ally with the Portuguese to force the Queen out of Zanzibar by 1652.36

By the late 1690s, there were further rebellions led by Mombasa and Pate which invited the Ya'rubids to oust the Portuguese, but stone-town's elites didn't feature in this revolt. Stone-town’s queen Fatuma Binti Hasan was still a Portuguese ally by the time of the Ya'rubid siege of fort Jesus in 1696-1698, and her residence was located next to the church at Forodhani. Stone-town and other allied Swahili cities sent provisions to the besieged Portuguese and allied forces at Fort Jesus, which invited retaliation from the Ya'rubids and allied cities.37

After expelling the Portuguese, the Ya'rubids imposed their authority on most of the Swahili coast by 1699 by placing armed garrisons in several forts, and deposing non-allied local elites like Fatuma to Oman. In stone-town, the church at Forodhani was converted into a small fortress by 170038.

But Yaʿrubid control of the Swahili coast was lost during the Omani civil war from 1719 to 1744, during which time stone-town was ruled by Fatuma's son Hasan.39 This war was felt in stone-town in 1726, when a (Mazrui) Omani faction based in Mombasa attacked a rival faction in stone-town, resulting in a five-month siege of the Old Fort. The defenders left stone-town, and the Portuguese briefly used this conflict to reassert their control over Mombasa and stone-town from 1728 and 1729 but were later driven out. Stone-town reverted to the authority of the so-called Mwinyi Mkuu dynasty of local elites.40

Other towns on the island such as Kizimkazi continued to flourish under local control during the mid to late 18th century.41 According to traditions, the population of southern Zanzibar extending from Stone-town to Kizimkazi were called the maKunduchi (kae) while those in the northern section of the island were called the waTumbatu. Kizimikazi's mosque was expanded around the year 1770 and this construction is attributed to a local ruler named Bakari who controlled the southern most section of the island.42

Zanzibar from 1753-1873: From local autonomy to Oman control.

Zanzibar's polities remained autonomous for most of the 18th century despite attracting foreign interest. In 1744, political power in Oman shifted to the Bu’saidi dynasty, who for most of the 18th century, failed to restore any of the Yaʿrubid alliances and possessions on the Swahili coast, except at stone-town.43

The Mwinyi Mkuu of stone-town sought out the protection of the Bu'saidi as a bulwark against Mazrui expansion, and allowed a governor to be installed in the old fort in 1746. The Mazrui would later besiege stone-town in 1753 but withdrew after infighting. Despite the alliance between stone-town's elites and the Busaidi, the latter's control was constrained by internal struggles in Oman and only one brief visit to stone-town was undertaken in 1784 by the then prince Sultan bin Ahmad.44

Sultan bin Ahmad later ascended to the Oman throne at Muscat in 1792 but died in 1804 and was succeeded by his son Seyyid Said. Events following the victory of Lamu against Mombasa and Pate around 1813, compelled the Lamu elites to invite Seyyid's forces and stave off a planned reprisal from Mombasa. Seyyid forged more alliances along the coast, garrisoned his soldiers in forts and increasing his authority in stone town.45

In 1828 Said bin Sultan made the first visit by a reigning Busaid sultan to the Swahili coast, shortly after commissioning the construction of his palace at Mtoni. His visits to Zanzibar became increasingly frequent, and by 1840 stone-town had become his main residence. Contrary to earlier scholarship, the shift from Muscat to stone-town was largely because Seyyid's authority was challenged in Oman, while stone-town offered a relatively secure location for his political and commercial interests.46

Seyyid's control of stone-town was largely nominal as it was in Lamu, Pate and Mombasa. Effective control amounted to nothing more than a nominal allegiance by the local elites (like in Tumbatu and stone-town) who retained near autonomy, they occasionally shared authority with an appointed 'governor' and customs officer assisted by a garrison of soldiers.47

The Mwinyi Mkuus ruled from their capital at Mbweni during the reign of Seyyid (1840-1856) and his successor Majid (1856-1870). The most notable among whom was Muhammad bin Ahmed bin Hassan Alawi also known as King Muhamadi (1845-1865), he moved his capital from Mbweni to Dunga where he built his palace in 1856. He held near complete political power until his death in 1865, and was succeeded by his son Ahmed bin Muhammad48.

The last Mwinyi Mkuu Ahmed died in 1873, and the reigning Sultan Barghash (r. 1870-1888) refused to install another Mwinyi Mkuu, formally marking the end of Stone-town’s autonomy.49 The gradual expansion of Sultan Barghash's authority followed the abolition of the preexisting administration, and the island was governed directly by himself shortly before most of his domains were in turn taken over by the Germans and the British in 188550.

The Mwinyi Mkuu of stone-town; Muhammad bin Ahmed bin Hassan Alawi, with his son, the last Mwinyi Mkuu Ahmed.

The Mwinyi Mkuu’s palace at Dunga, ca. 1920

Zanzibar was one of several cosmopolitan African states whose envoys traveled more than 7,000 kilometers to initiate contacts with China, Read more about this fascinating history here:

Map by Ania Kotarba-Morley

Continental Island Formation and the Archaeology of Defaunation on Zanzibar, Eastern Africa, M Prendergast et al

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 107, 138)

The Swahili: Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society pg 50-51

The Swahili and the Mediterranean worlds by A. Juma pg 148-153

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 142, 109, 241)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 143, 170-174)

Unguja Ukwu on Zanzibar by A. Juma pg 19-20, 62, 73, 137,-143

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 241, 489-490)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 170)

Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture by by J. de V. Allen pg 186, 146, The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 372)

Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture & the Shungwaya Phenomenon By James De Vere Allen pg 146, 186-188

The Battle of Shela by RL Pouwels pg 381)

Unguja Ukwu on Zanzibar by A. Juma pg 140

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 143-144, 241)

East Africa in the Early Indian Ocean World Slave Trade by G. Campbell pg 275-281, The Zanj Rebellion Reconsidered by G. H. Talhami (A. Popovic’s critique of Talhami relies solely on medieval texts to estimate the first coastal settlements and their links to the Zanj, this is taken on by M. Horton but the evidence on the ground is lacking as G. Campell argues)

Estimates for the population of rebelling slaves in 800-870 revolt would have required a volume of trade just as high as in the 19th century when the trade was efficiently organized, making them even more unlikely, see “Early exchanges between Africa and the Indian ocean world by G Campbell pg 292-294,

The one contemporary source was al-Jāḥiẓ (d. 868), himself a grandson of an ex-slave, wrote that captives came from “forests and valleys of Qanbuluh” [Pemba] and they are not genuine/native Zanj but were “our menials, our lower orders” while the native Zanj “are in both Qambalu and Lunjuya [Unguja—Zanzibar]”, taken from “Early exchanges between Africa and the Indian ocean world by G Campbell pg 290

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 78

Slave Trade and Slavery on the Swahili Coast 1500–1750 by Thomas Vernet

Unguja Ukwu on Zanzibar by A. Juma pg 84, 154

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 242)

Excavations at the Old Fort of Stone Town, Zanzibar by Timothy power and Mark Horton pg 278)

The Indian Ocean and Swahili Coast coins by John Perkins

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 242, 493)

A Thousand Years of East Africa by JEG Sutton’

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 242

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 243)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 69)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 83-84, 88)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 119-128, 88)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 243, Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 87, Excavations at the Old Fort of Stone Town, Zanzibar by Timothy power and Mark Horton pg 281, Swahili Culture Knappert pg 144) )

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 243)

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 39-43)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 165)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 301-302, Excavations at the Old Fort of Stone Town, Zanzibar by Timothy power and Mark Horton pg 281)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 373, The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 243)

Zanzibar Stone Town: An Architectural Exploration by A. Sheriff pg 8, Excavations at the Old Fort of Stone Town, Zanzibar by Timothy power and Mark Horton pg 284)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 531)

Trade and Empire in Muscat and Zanzibar By M. Reda Bhacker pg 80, Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar by Abdul Sheriff pg 26-27)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones pg 295)

The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, pg 247, The African Archaeology Network by J Kinahan pg 110

Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar by Abdul Sheriff pg 20-21)

Excavations at the Old Fort of Stone Town, Zanzibar by Timothy power and Mark Horton pg 285, The Land of Zinj By C.H. Stigland pg 24)

The Battle of Shela by RL Pouwels, Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 99)

Trade and Empire in Muscat and Zanzibar By M. Reda Bhacker pg 88-95, 99-100)

Trade and Empire in Muscat and Zanzibar By M. Reda Bhacker pg 97)

Seyyid Said Bin Sultan by Abdallah Salih Farsy pg 34-35

Seyyid Said Bin Sultan by Abdallah Salih Farsy pg 35

Swahili Port Cities: The Architecture of Elsewhere by Sandy Prita Meier 103-105