A network of African scholarship and a culture of Education: The intellectual history of west Africa through the biography of Hausa scholar Umaru al-Kanawi (1857-1934)

The school systems of precolonial Africa.

Research on Africa's intellectual history over the last few decades has uncovered the comprehensiveness of Africa's writing traditions across several societies; "There are at least eighty indigenous African writing traditions and up to ninety-five or more indigenous African writing traditions which belong to a major writing tradition attested to all over the continent". Africa has been moved from "continent without writing" to a continent whose written traditions are yet to be studied, and following the digitization of many archival libraries across the continent, there have been growing calls for a re-evaluation of African history using the writings of African scholars.1

West African has long been recognized as one of the regions of the continent with an old intellectual heritage, and its discursive traditions have often been favorably compared with the wider Muslim world of which they were part. (West Africa integrated itself into the Muslim world through external trade and the adoption of Islam, in the same way Europe adopted Christianity from Palestine and eastern Asia adopted Buddhism from India during the medieval era). West African intellectual productions are thus localized and peculiar to the region, its education tradition developed within its local west African context, and its scholars created various ‘Ajami’ scripts for their languages to render sounds unknown in classical Arabic. These scholars travelled across several intellectual centers within the region, creating an influential social class that countered the power of the ruling elite and the wealthy, making African social institutions more equitable.

This article explores the education system of pre-colonial west Africa, and an overview of the region's intellectual network through the biography of the Hausa scholar Umaru al-Kanawi, whose career straddled both the pre-colonial and colonial period, and provides an accurate account of both eras of the African past.

Map of the intellectual network of 19th century westAfrica through which Umaru travelled

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

West Africa’s intellectual tradition: its Position in world history, its Education process, and the social class of Scholars.

The political, economic and social milieu in which Islam was adopted across several west African states resulted in the incorporation of its aspects into pre-existing social structures, one of these aspects was the tradition of Islamic scholarship that flourished across several west African cities beginning in the 11th century. The quality of west African scholarship and its extent is well attested in several external and internal accounts. As early as the 12th century, a west African scholar named Yaqub al-Kanemi (“of Kanem”) who had been educated in west African schools became a celebrated grammarian and poet of the Moroccan and Andalusian (Spanish) courts 2, in the 14th century, an Arab scholar accompanying Mansa Musa on his return trip from mecca realized his education was less than that of the resident west African scholars and was forced to take more lessons in order for him to become a qualified teacher in Timbuktu.3 Several external writers, including; Ibn Battuta in the 14th century, Leo Africanus in the 16th century, Mungo Park in the 18th century, and colonial governors in the 19th and 20th century, testified to the erudition of west African scholars, with French and English colonial officers observing that there were more west Africans that could read and write in Arabic than French and English peasants that could write in Latin4. The terms "universities of Timbuktu" or "university of Sankore", despite their anachronism, are a reflection of the the advanced nature of scholarship in the region’s intellectual capitals.

painting of 'Timbuctoo' in 1852, by Johann Martin Bernatz, based on explorer H. Barth’s sketches; the three mosques of Sankore, Sidi Yahya and Djinguereber are visible.

Education process in west africa: teaching, tuition and subjects

The scholarly tradition of west Africa was for much of its history individualized rather than institutionalized or centralized, with the mosques only serving as the locus for teaching classes on an adhoc basis, while most of the day-to-day teaching processes took place in scholar's houses using the scholar's own private libraries.5 The teacher, who was a highly learned scholar with a well established reputation, chose the individual subjects to teach over a period of time; ranging from a few months to several years depending on the level of the subject's complexity. The students were often in school for four days a week from Saturday to Tuesday (or upto Wednesday for advanced levels), setting off Wednesdays to work for their teachers, while Thursday and Friday are for rest and worship. By the 19th century, individual students paid their teachers a tuition of 30,000-10,000 cowries6 every few months, to cover the materials used (paper, ink, writing boards, etc), and for the expenses the teacher incurs while housing the students, and the teachers also redistributed some of their earnings in their societies as alms.7

Hausa writing boards from the 20th century, Nigeria, (Minneapolis institute of arts, fine arts museum san francisco)

Elementary school involved writing, grammar, and memorizing the Quran, and often took 3-5 years. Advanced level schooling was where several subjects are introduced, for the core curriculum of most west African schools, these included; law/Jurisprudence (sources, schools, didactic texts, legal ̣ precepts and legal cases/opinions), Quranic Sciences, Theology, Sufism, Arabic language (literature, morphology, rhetoric, lexicons), studies about the the Prophet (history of early Islam, devotional poetry, hadiths)8. The more advanced educated added dozens of subjects included; Medicine, Arithmetic, Astronomy, Astrology, Physics, Geography, and Philosophy among others.9 At the end of their studies, the student was awarded with an ijazah by their teacher, this was a certificate that authorized the student to teach a subject, and thus linked the student to their teacher and earlier scholars of that subject.10 More often than not, a highly learned student would at this stage compose an autobiography, listing the subjects they have studied from each teacher.

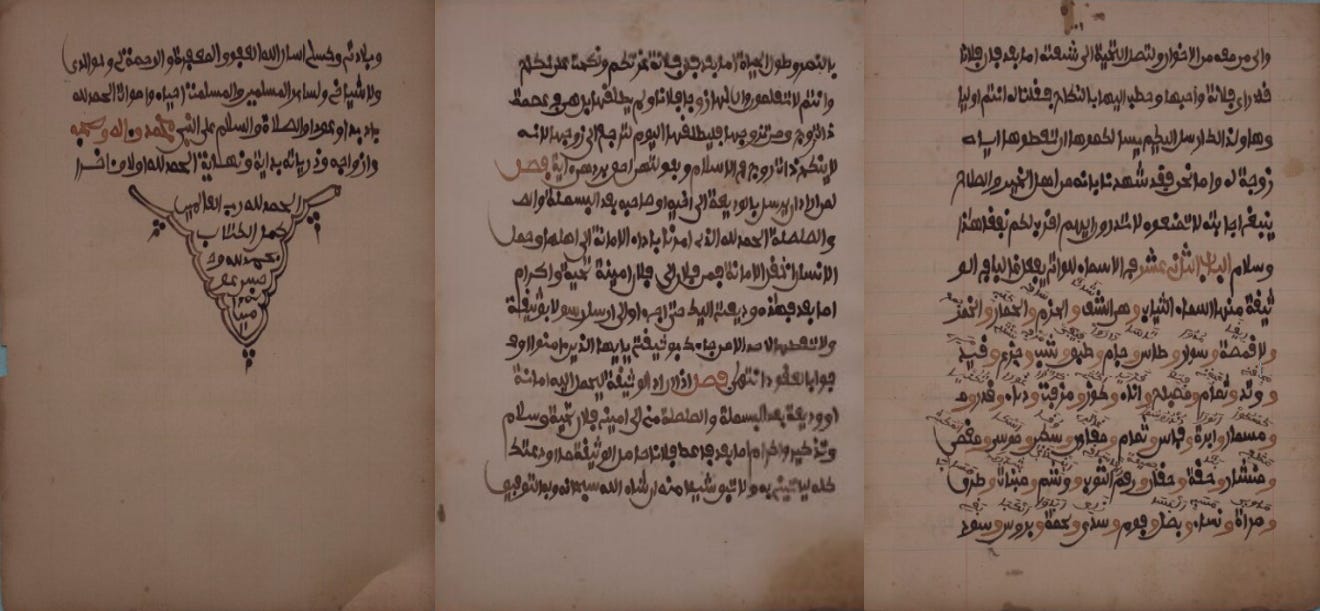

19th century manuscript by the philosopher Dan Tafa from Sokoto (Nigeria) listing the subjects he studied from various teachers (see article about him). Astronomical manuscript from Gao, (Mali) written in 1731.

Creating an intellectual network and growing a scholarly class: the Ulama versus the rulers, and the Ulama as the rulers.

A common feature of west African teaching tradition (and in the wider Muslim world) was the preference by advanced-level students to travel across many scholarly centers to study different subjects from the most qualified scholar, rather than acquire them from one teacher (even if the teacher was familiar with many subjects).11 Upon completing their studies, the students would often set out to establish their own schools. This "itinerant" form of schooling at an advanced level —which was especially prevalent in west African scholarly communities that didn't often practice the endowment of "fixed" colleges/madrassas12—, offered several advantages; besides greatly reducing the cost of establishing schools. The most visible advantage was the challenge faced by west African rulers in their attempts at bringing the scholarly class (Ulama) under central authority, this created the long-standing antagonistic dynamic between the Ulama and the ruling elites which served as a check on the authority of the latter —since the latter's legitimacy partly rested on concepts of power derived from the former— and resulted in both scholars and rulers maintaining a delicate equilibrium of power.13

The Ulama were incorporated as one of the several "castes" in west Africa's social structures and were thus often excluded from direct political power despite their close interaction with rulers14. This also meant the Ulama were not unaccustomed to condemning the excesses of the rulers as well as the wealthy merchant-elite, an example of this were the longstanding disputes between the scholars based in Timbuktu and Djenne, and the ruling class of the Songhai empire; eg when the djenne scholar Maḥmūd Baghayughu criticized the double taxation of Songhai emperor Askia Isḥāq Bēr (r. 1539-1549), the latter managed to short-circuit this challenge of his authority by appointing Baghayughu in the local government of Djenne putting him in charge of the very same taxation he was criticizing, Ishaq was employing the same political stratagem which his predecessors had used to curb the power of the Timbuktu-based Ulama15. A similar antagonism between rulers and scholars prevailed in the Bornu empire, where the scholar Harjami (d. 1746) composed a lengthy work condemning the corruption, bribery and selfishness of Bornu's rulers, judges and wealthy elite.16 Harjami’s text became popular across west Africa and Egypt and was used by later scholars such as Sokoto founder Uthman Fodio in their critique of their own ruling elites17. The influence a scholar like Harjami had that enabled him to openly challenge authority is best summarized by Umaru who writes that; "this type of Malam (teacher/scholar) has nothing to do with the ruler and the ruler has nothing to do with his, he is feared by the ruler".18 Nevertheless, Bornu’s rulers also found ways to counter the challenge presented by such scholars, they granted some of the Ulama charters of privilege, generous tax advantages and land grants, which led to the emergence of official/state chroniclers such as Ibn Furṭū who wrote accounts of their patron's reigns.19

a critique of Bornu’s corruption by the 18th century Kanuri scholar Harjami in Gazargamu, Bornu (Nigeria)

copies of the 16th century chronicles of Bornu, written by state chronicler Ahmad Ibn Furtu in Gazargamu, Nigeria (now at SOAS london)

By the 18th and 19th century, some among the Ulama were no longer seated on the political sidelines but overthrew the established authorities and founded various forms of "clerical" governments in what were later termed revolution states20. Because of the necessities of governing, these clerical rulers left their itinerant tradition to became sedentary, establishing themselves in their capitals such as Sokoto, Hamdallaye, which became major centers of scholarship producing some of the largest corpus of works made in west african languages (rather than arabic). These clerical rulers’ radical shift away from itinerant tradition of education (and trade) to a settled life in centers of power, was such that despite their well-deserved reputation as highly educated with expertise on many subjects, few of them made the customary Hajj pilgrimage21. On the other hand, the majority of west African scholars chose to remain outside the corridors of power, especially those engaged in long distance trade which put them in close interaction with non-Muslim states eg in the region of what is now ivory coast and ghana. Most of these scholars followed an established philosophy from the 15th century west African scholar Salim Suwari whose dicta outlined principles of co-existence between the Ulama in non-Muslim states and their rulers.22 These scholars therefore continued practicing the itinerant form of schooling and teaching, they established schools in different towns and remained critical of the ruling elite (including the later colonial governments). The biography of the Hausa scholar Umaru al-Kanawi (b.1858 – d.1934) embodies all these qualities.

photo of alHaji Umaru in the early 20th century.

Short biography of Umaru: from Education in Kano (Nigeria), to trade in Salaga (Ghana) and to settlement in Kete (Togo)

Umaru was born in the Kano in 185723 (Kano was/is a large city in the ‘Hausalands’ region of what is now northern Nigeria, and was in the 19th century under the Sokoto empire). He begun his elementary studies in the city of Kano at the age of 7, and had completed them at the age of 12. He immediately continued to advanced level studies in 1870 and had completed them by 1891. In between his advanced-level studies, he would accompany his father on trading trips to the city of Salaga in what is now northern Ghana (an important city connected to the Hausalands whose primary trade was kolanuts), from where he would occasionally take a detour away from the trading party to find local teachers and read their libraries. Umaru composed his first work in Kano in 1877; it was a comprehensive letter writing manual titled "'al-Sarha al-wariqa fi'ilm al-wathiqa" (The thornless leafy tree concerning the knowledge of letterwriting).24 He wrote it as a request of his friends in Kano who wanted standard letters to follow in their correspondence. The epistolary style and formulae used in his work outlined standard letter writing between merchants of long-distance trade, letter writing to sovereigns, and letter writing for travelers on long distances.25

Umaru’s first work in 1877 (at the age pf 20); a 20-page letter writing manual; now at Kaduna National Archives, Nigeria (no. L/AR20/1)26

After his father passed away in 1883, Umaru moved to Sokoto for further studies, as well as to the cities of Gwandu and Argungu where he spent the majority of his time. Umaru also travelled to the lands of Dendi-Songhai, Mossi and Gurunsi for further studies between the years 1883 and 1891. Umaru completed his studies in 1891 at the age of 34 and was awarded his certificate by the teacher Sheikh Uthman who told him "you are a very learned man and it is time that you go and teach". During and after his studies, Umaru composed hundreds of books of which several dozen survive, most of them were written in Hausa and some in Arabic. Umaru decided to leave the Hausalands to settle in Salaga in 1891, a city which was familiar to him and where his relatives were already established.27 He arrived at Salaga when it —and much of northern Ghana— was in the process of being colonized by the British and the Germans, and the Anglo-German rivalry for the domination of the region continued until world war I. In Salaga, Umaru had many students including among his Hausa merchant community and the residents of the city, one of Umaru's students was the German linguist Gottlob Krause (d. 1938), an unusual figure among the crop of European explorers at the time, his interests appear to have been solely scientific, he was opposed to both colonial powers and lived off trade to support his research in Hausa history and language, he spoke Hausa fluently (the region’s lingua franca) and took on the name Malam musa, he studied under Umaru for a year until he left the town in 1894.28 Umaru also left Salaga shortly after, as the Asante kingdom’s withdraw from the town following the British defeat in 1874 had left the area volatile, leading to a ruinous civil war in 1891-1892 from which it didn’t recover its former prominence.

Umar’s birthplace; The city of Kano, Nigeria. photo from the mid 20th century

Umaru moved to Kete-Krachi in 1896, in what was by the German colony of Togo, who had just seized the town in 1894.29 It was at Kete that he composed many of his works on west African history and society. Umaru had several students at Kete and when a dispute arose over the choice of an imam, the newly appointed German administrator of Kete in 1900, named Adam Mischlich, resolved it by asking the rival contenders to read the famous Arabic dictionary al-Qāmūs by Firuzabadi (d. 1414) which Umaru was familiar with. Adam then became a student of Umaru, studying everything he could from him about the history and society of the Hausalands region (this was a personal interest since the Hausalands were firmly under British occupation with the only other contenders being the French). Adam wrote of his studies under Umaru as such; "… the intelligent and very gifted Imam Umoru from Kano, who having travelled through Hausaland and the Sudan, lived in Salaga, and had finally come to Kete, In Togo, He was in possession of a very well stocked library … Imam Umaru had seen and come to know a great part of africa, had broadened extraordinarily his intellectual horizon and could give information on any matter. He knew exactly the history of his country".30

Umaru’s written works with critiques of the rulers of Sokoto and Salaga, and his anti-colonial writings against the British, French and Germans.

Umaru’s works were often critical of the established governments in the places he lived and moved to; he strove to maintain a distance from the ruling authorities despite interacting with them, and his compositions of west African history reflect his mostly independent status outside the political apparatus. He was critical of the clerical rulers of Sokoto (that dominated the Hausalands) despite his identification with their religious aims.31 Writing that the rulers of Sokoto

"came into Kebbi and they were office-holders. The former (Sokoto rulers) who were non-powerful, now conquered much, but they were not careful with their conquest. When they wanted to lodge at a house, they would tie the harnesses (of the horses) in the courtyard (it was not supposed for animals to enter it). There was no speaker (for the Kebbi people)".32

In another work ‘Tanbih al-ikhwān fi dhikr al-akhzān’ written in 1904, Umaru criticized the rulers of Salaga and the Muslim community there for their part in the civil war (as they had broken their non-participation custom to back one of the rivaling rulers who ultimately lost). he wrote that

“The people followed their whims and became corrupt, they gathered money and were overproud. They created enmity among themselves, hatred and distasteful cheating; In their town there was much snatching: salt, meat, alum, and cowries were taken from the market; clothing likewise. The rulers acted so tyrannically in public that they made their village like a cadaver on which they sat like vultures."33

Umaru’s anti-colonial works:

Despite the presence of a colonial administrator as one of his students, Umaru's writing was unsurprisingly critical of colonialism, he composed three works in 1899, 1900 and 1903 that were wholly negative of the colonial government. One of his works in particular, titled ‘Wakar Nasara’ (Song of the Europeans) coolly summarizes the process of colonization of west Africa. He used the term Nasara (translated: Christian/European/Whiteman) to mean British, French and German colonial officers.34

"At first we are here in our land, our world.

Soon it was said, "there is no kola" and people said there was warfare between the Asante and the whiteman. Still later it was said, "Oh Asante is finished! their land, all of it, has been seized by the whiteman!"

As time went on, people said, Samory has come. He says that he will not run from the whiteman! He has his warriors and troops an other things he will use against the white man" Oh, lies were being told by the people, for the whiteman was able to drive him from his town and seize it!

Samory is seeking to lead but he was behind, looking over his shoulder to see if the whiteman was coming! As time went on, Prempeh got the news. Prempeh heard of Malam Samory who hated the whiteman. Immediately he sent messengers to him: "let us bring our heads together and route the white man!"

But the whiteman got wind of the news, and with cunningness seized Prempeh. Then they begun to march on Samory; the French, the English, both whitemen. Then Samory found himself caught in their hands: caught and taken to the town of the whiteman”

(This is a reference to the British-Asante war of 1874, the attempted alliance between Samory Ture and the Asante king Prempeh in 1895, and the subsequent British occupation of Asante in 1896 and exile of Samory in 1898; read more about it in this article )

he continues …

“Amhadu of Segu was an important ruler. At Segu, the whiteman descended upon him. His brother Akibu was responsible for that, for he called the whiteman. Amhadu was driven from the town and went as Kabi, for he was angry having been driven out. It was there that he died, may God bless his soul.

When they came to the land of Nupe, our Abu Bakr refused to follow the whiteman. Circumstances forced him to set out and leave his home: he was running being chased by the whitemen. They were racing, Abu Bakr and the whitemen; the whitemen were in pursuit, until they grabbed him.

And in Zinder, Jinjiri made the costly mistake, he killed a white man; He caught hell, having killed the leader of the French, Sagarafa (white man) came at top speed with the soldiers; jinjiri confronted them; There is destruction on meeting the whiteman. It was there that Jinjiri was killed on the spot, along with his people. Oh, cruel whiteman. And then the whiteman ruled Zinder"35

(These verses refer to several wars between the French and the Tukulor empire under Amhadu Tall in the 1890s, the war between the British and the Nupe under Abubakar in 1897, the 1898 assassination of Cazemajou, the leader of the French invading force, and the subsequent French occupation of Zinder in 1899)

Umaru against wealth inequality:

Umaru drew students from across the region, and these inturn became scholars of their own right, He occasionally travelled from Kete such as in 1912 when he went for pilgrimage, returning in 1918 to find that the British had taken over the Togo colony. He composed other works and over 120 poems, and wrote other works on Hausa society including one titled ‘Wakar Talauci da wadata’ (Song of poverty and of wealth) that was written in the 1890s, and decried the wealth inequality in Hausa communities.

excerpt:

"If a self-respecting man becomes impoverished, people call him immoral; but that is unfounded. The poor man does not say a word at a gathering; his advice is kept in his heart. If he makes a statement on his own right, they say to him, "Lies, we refuse to listen!" They muddle up his statements, mix-up what he says; he is considered foolish, the object of laughter".36

Umaru passed away in 1934 after completing a new mosque in Kete, in which he was later buried. On the day of his burial, a student eulogized him in a poem; "God created the sun and the moon, today the two have vanished"

photo from 1902 showing a rural mosque under construction at Kete-Krachi in Ghana (then Kete-Krakye in German Togo), Basel Mission archives

Conclusion: Re-evaluating African history using the writings of Africans.

The legacy of Umaru’s intellectual contribution looms large in west African historiography. His very comprehensive 224-page description of pre-colonial Hausa society that covered everything from industry to agriculture, kinship, education, religion, child rearing, recreation, etc, is one of the richest primary accounts composed by an African writer37, and his history books on the various kingdoms of the "central Sudan" (in what is now Nigeria and Niger) are an invaluable resource for reconstructing the region's history.38

Scholars like Umaru were however not a rarity, but a product of the 1,000 year old West African scholarly tradition and intellectual network, which created a social class of scholars that checked the excesses of rulers and the wealthy elite, and wrote impartial accounts of African societies that were unadulterated by the biases of external and colonial writers.

The writings of Umaru enable us to re-evaluate our understanding of African societies, revealing the complex nature in which power was negotiated, history was remembered and an intellectual culture flourished. In his writings, Umaru paints a fairly accurate portrait of Africa as seen by Africans.

read about African ‘explorers’ in 19th century Russia and northern Europe, and books on Africa’s intellectual history on my Patreon

(you can download these books listed below from my patreon)

The Arabic Script in Africa: Understudied Literacy by Meikal Mumin pg 41-76

Arabic literature of africa Vol. 2 by J. Hunwick pg 18-19

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 73-74)

Beyond timbuktu by Ousmane Oumar Kane pg 7-8)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg lviii-lix)

these are 19th century figures, equal to about the cost of an expensive garmet, or roughly £3 in 1850, a class with a few dozen students could thus provide enough sustenance for the teacher (see pg 98 of Cloth in West African History By Colleen E. Kriger)

Nineteenth Century Hausaland: Being a Description by Imam Imoru of the Land, Economy and Society of His People by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 260-265)

The Trans-Saharan Book Trade by Graziano Krätli pg 109-152)

Philosophical Sufism in the Sokoto Caliphate: The Case of Shaykh Dan Tafa by Oludamini Ogunnaike pg 144-147)

Nineteenth Century Hausaland by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 9)

The SAGE Handbook of Islamic Studies by Akbar S Ahmed pg 10-11)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg lix)

African dominion by Michael A. Gomez pg 193-207)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by M. Nobili pg 18)

African Dominion by M. Gomez pg 265-279

The Kanuri in Diaspora by Kalli Alkali Yusuf Gazali , pg 43

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 2 by J. Hunwick pg 39-41

Nineteenth Century Hausaland by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 265)

(Aḥmad b. Furṭū, homme de cour, observateur du monde in Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière)

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith by M. Nobili pg 13-19)

Geography of jihad Stephanie Zehnle 198-208)

The History of Islam in Africa by N. Levtzion pg 97-99)

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 2 by J. Hunwick pg 586

Arabic Literature of Africa, Volume 2 by J. Hunwick pg 590)

Nineteenth Century Hausaland by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 32)

Nineteenth Century Hausaland by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 8-13)

Nineteenth Century Hausaland by Douglas Edwin Ferguson 19th pg 17-18)

Nineteenth Century Hausaland by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 20)

Nineteenth Century Hausaland by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 26-27)

Imam Umaru's account of the origins of the Ilorin emirate by Stefan Reichmuth 159)

Geography of jihad Stephanie Zehnle pg 285-290)

“Salaga a trading town in Ghana” by Nehemiah Levtzion in ‘Asian and African Studies: Vol. 2’ pg 239, Nineteenth Century Hausaland by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 15-16

Hausaland Divided: Colonialism and Independence in Nigeria and Niger By William F. S. Miles pg 100-103

Nineteenth Century Hausaland by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 29-30)

Nineteenth Century Hausaland by Douglas Edwin Ferguson pg 34)

see a full translation of his magnu opus in “Nineteenth Century Hausaland” by Douglas Edwin Ferguson

see “Imam Umaru's Account of the Origin of the Ilorin Emirate” by S Reichmuth, Northern Nigeria; historical notes on certain emirates and tribes by J A Burdon, and more excerpts in “A Geography of Jihad” by Stephanie Zehnle

This is interesting information I mean I know that West Africa long had a rich intellectual history that spanned centuries in particular the Islamic tradition is West Africa is considered to be among the most respected in Islamic history even outside of Africa but like even then the Pre-Islamic intellectual history is interesting too though needs more studied as well either way your work is amazing keep it up I always like to read up on info you post.

Hello,

I enjoy your content and would like to learn more about your background and possibly invite you to be interviewed on The Leopard Society show. Can I have your email or can you email me at theleopardsociety@protonmail.com ?