A political history of the Kotoko city states (ca. 1000-1900)

Urbanism and state building in the lake chad basin..

The parched floodplains of the lake chad basin were home to Africa's most enigmatic urban societies. Enclosed within monumental walls was a maze of palaces, towering fortresses, flat-roofed houses, and vibrant markets intersected by narrow streets.

The cities of Kotoko were organized into state-level societies in which urbanism played an essential role. Situated at the center of regional exchange systems but on the frontier of expansionist empires, the city states flourished within a contested political environment.

This article outlines the history of the Kotoko city-states. Beginning with the emergence of the oldest urban state at Houlouf, to the consolidation of the cities under the kingdom of Logone.

Map of the Lake chad basin in the 16th century showing the location of the Kotoko city-states.1

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The early history of Kotoko: from incipient states to the Houlouf chiefdom

The south-eastern margins of lake chad were settled by speakers of Central Chadic languages around the early 2nd millennium BC and established a number of Neolithic settlements and incipient states. Among these were speakers of the proto-Kotoko language who occupied the floodplains of the Logone river basin.2

The earliest settlements along the Logone river are dated to the Deguesse Phase which begun in 1900BC to the turn of the common era. The region was home to mobile herders who set up semi-permanent pastoral camps at Deguesse and Krenak that were contemporaneous with the Gajigana Neolithic on the western shores of the lake.3 In the succeeding Krenak and Mishiskwa settlement phases that ended around 1000 AD, the iron-age settlements at the sites of Deguesse, Krenak and Houlouf grew into autonomous self-sustaining communities, and later into the centers of small polities. They had a mixed agro-pastoral economy, with access of aquatic resources of the logone delta.4

The site of Houlouf became the largest among the urban clusters of the Ble phase (1000-1400 CE) when a 16-hectare earthen rampart was built around it. The emerging urban settlement at Houlouf became the capital of local chiefdom, following a period of increased warfare due to peer-polity competition among the small polities, and the formation of a "warrior-horsemen" class, which necessitated the construction of defensive walls. As a major political center of substantial polity, Houlouf had a rich royal cemetery, a large palace and an extensive city wall.5

At its height in the 16th century the Houlouf polity had a hierarchical political system headed by a chieftain (Mra/Sultan), and a diverse political system of elite groups comprising administrators and tribute collectors such as the chief of the land (galadima), military heads for horsemen and archers, and ritual specialists for religious events and rites. These were organized into factions that also controlled access to long-distance luxury goods obtained from regional markets and across the Sahara.6

The city of Houlouf is the most likely candidate for the city of Quamaco/Quamoco mentioned by the 16th century geographer Lorenzo d'Anania. His informant on the trade routes of the lake chad basin wrote that, “at Quamaco, there is a great traffic of iron that is carried from Mandrà [Mandara]" —Mandara being the kingdom in northern Cameroon, thus placing Quamaco south of lake chad in Kotoko country. 7

The capital of Houlouf was a large urban settlement, divided into six quarters each with a gate named after the different rulers of the chiefdom. It domestic space was built with the typical rectangular mud-brick houses with flat roofs, organized into walled compounds within the city quarters.8 It had a substantial crafts industry that included cloth production and dyeing, metallurgy and smithing, fish processing, as well as salt mining and trade.9

The ramparts of Houlouf, ca 1930, photo by A. Holl

Holouf cemetery and a copper-alloy figurine of a horseman, 11th-15th century, photos by A. Holl

The Kotoko city-states.

All across the Logone river basin, city-states emerged whose political trajectory mirrored that of Holouf; beginning as small walled communities and growing into the walled capitals of autonomous chiefdoms. Like Holouf, they were predominantly settled by Kotoko/Lagwan speakers of Chadic languages, although each spoke a different dialect.10

They had a mixed agro-pastoral and fishing economy with a substantial crafts industry, and were marginally engaged in long distance trade both regionally and across the sahara. More than 20 Kotoko city-states are known from this period, including Logone-Birni, Waza, Zgague, Zgue, Djilbe, Tilde, Kala-Kafra, and Kabe as well as; Goulfey, Makari, Afade, Maltam, Kusseri, Sao, Woulki, Waza, Midigué, Tago, Gawi, Amkoundjo, and Messo. 11

The biggest of these Kotoko cities are mentioned by both the 16th century Bornu scholar Ibn Furtu and the Italian geographer Lorenzo d'Anania. For the latter's account in particular; the best known cities include; Makari (Macari) , Gulfey (Calfe) , Afade (Afadena) , Wulki (Ulchi) , Kusseri (Uncusciuri) , Sao (Sauo) and Logone (Lagone).12

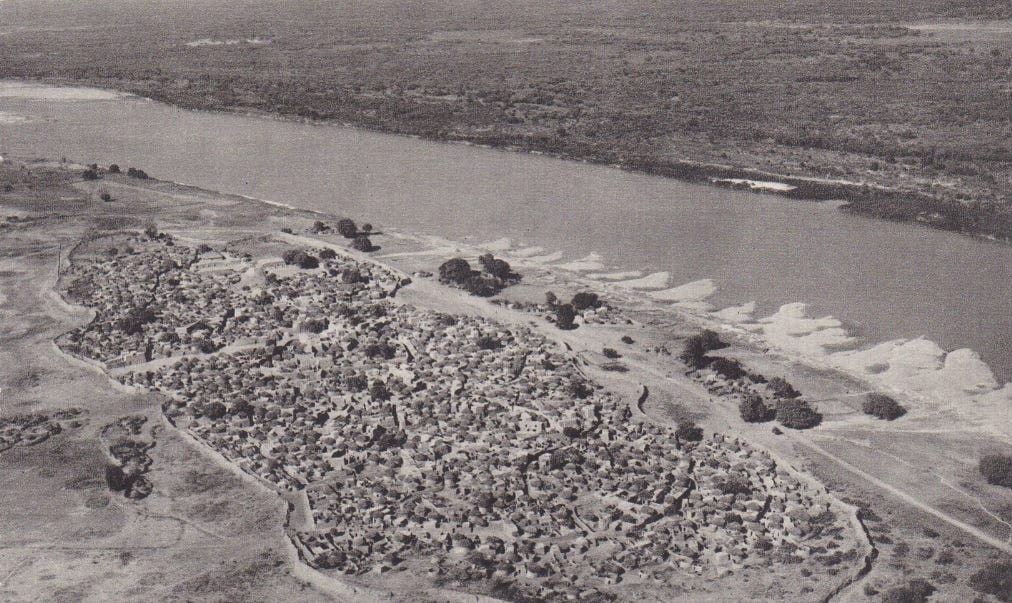

Aerial photo of Gulfey, and the mosque of Kusseri in the early 20th century, quai branly

Walled sections of Afade and Wulki, 1936, quai branly

Kotoko cities between the empire of Bornu and the emergence of the Logone kingdom (16th century-18th century)

Begining in the 16th century, the social and political landscape of south-eastern chad was profoundly altered by the expansion of the state of Bornu and the arrival of nomadic shuwa-Arab pastoralists. The Bornu empire had been active in the south-eastern chad region since the mid-16th century. In the 1560s, Mai Idris Alooma's armies campaigned in the region as part of Bornu's attempt to retake control of the region east of lake Chad. Bornu's armies only reached the northern Kotoko cities, capturing the ruler of Kusuri (Kusseri) whose chiefdom was turned into a vassal, and sacking the city of Sabalgutu.13

The threat posed by Bornu empire resulted in the formation of two main confederations. The northern cities were under the ruler of Makari, who is reported to have joined the Bornu armies in campaigning directed against other polities on the frontiers of Bornu. While the southern city-states were under the ruler Logone. It's during this period that Houlouf was subsumed under the expanding kingdom centered at Logone along with the first eight city-states listed above.14

Its through this process of political consolidation that the two major dialects of Makari and Lagwan (Logone) were created, with the former spoken in the northern cities, while the latter was spoken in the southern cities. But since the northern cities were often under the suzerainty of Bornu, both the language and the independent southern kingdom were commonly known in external accounts as Kotoko, following the exonymous term "Katakuwā" used in Bornu.15

Conversely the nomadic Shuwa-Arab groups became subordinate to the Kotoko kingdom in a broad range of tribute payments where they submitted pastoral products to the rulers of Kotoko city-states in exchange for grazing rights. This subordinate relationship between the Shuwa Arabs and the various kingdoms of the Sahel belt is also attested in the neighboring states of Bornu, Bargimi, Wadai, and Darfur.16

The pre-existing social-political institutions of Holouf were maintained by the Logone rulers who left Holouf as a nearly autonomous vassal. According to the traditions about the expansion of Logone, the process of subsuming the neighboring city-states (especially Holouf and Kabe) involved a complex series of matrimonial alliances and diplomacy rather than outright military conquest.17

The government at Logone was headed by the King and a state council of hereditary officials below which were numerous elites in a complex inflationary title system. The council was in charge of administration and policy, and it comprised high-ranking officials in the city and regional chiefs such as the pre-existing rulers of Holouf and other city-states. There was a permanent body of army officials led by the Mra Zina who was in charge of warfare, and an elaborate palace institution where subordinate chiefs were required to send their princes to the Logone palace to be raised by the king.18

The palaces at Logone-birni, and Gulfey

Kotoko cities in the 19th century: Trade, warfare and colonization.

Besides the traditional economic activities and exchanges involving agricultural, pastoral and marine products, the kingdom at Logone had a substantial textile industry inherited from the pre-existing polities it had subsumed. Cloth dyeing was a significant economic activity especially for the production of the tobe; a large prestige garment that was tinted with a shining black or blue color, and found high demand in Bornu.19

The city of Logone was visited by Major Denham in 1824 and by Heinrich Barth in 1852. Denham described the characteristic walled cities of Kotoko including Alph (Houlouf) and Kussery (Kusseri) as ruled by sultans that were at the time mostly independent of both Bornu and its emerging southern neighbor Bagirmi. Denham describes Logone (Loggun) as the capital of a large kingdom, it had a population of about 15,000 Kotoko speakers surrounded by countless shuwa-Arab dependents, and was neutral of the wars between Bornu and Bagirmi. The city had a vibrant cloth-making industry (with almost every house having a weaving loom), a busy market for regional and long-distance trade items that were exchanged using local metal currency. 20

In between Denham and Barth's visit, probably around 1830, Logone became a tributary of Bornu, paying a token tribute of 100 tobes and 10 captives to the Bornu ruler. Barth's account mentions the presence of Kotoko traders from Makari, Gulfeil, Kusseri, and Logone in the trading city of Angornu in Bornu, who exchanged dyed tobes for alloyed copper.21

By the 1870s, Kotoko confederations had grown into significant regional powers. The explorer Gustav Nachitgal describes the Kotoko cities as well built urban settlements that were relatively populous, with Kala Kafra's population at 6,000, Alph (Houlouf) at 7,000, and logon (Logone) at 12-15,000. Sultan Ma'aruf, the ruler of Logon at the time, was under the suzerainty of Bornu's ruler sheikh Omar (Umar I r. 1837-1881) in alliance with Makari, against the Bagirmi ruler Abd ar-Rahman II (r. 1870-1871) who was allied to Goulfey, Kusseri, and Wulki. The entire kingdom centered at Logone was estimated to cover about 8,000 sqkm comprising of several walled cities and towns of about 5,000 inhabitants for a total population of 250,000. Gustav observed that Logone’s urban population "devote themselves diligently to farming, fishing and industry" describing their vibrant cloth-dyeing industry, construction, and boat-building. 22

Over the late 19th century, the emergence of new expansionist states which greatly reduced the autonomy of the Kotoko cities. While the threat of Bagirmi was reduced by the southern expansion of the Wadai kingdom, the decline of Bornu enabled the ascendance of the warlord Rabeh, who carved up his own state based at Dikwa. Rabeh's forces occupied Kusseri and Logone in 1893, on his way to conquering Bornu. He established a short-lived state before he was ultimately defeated by the French in 1900.23 The Kotoko city-states remained a contested territory within the German and French spheres but ultimately fell to the latter in the early 20th century.

Aerial view of Logone-Birni, 1936, quai branly

The kingdom of Kush in ancient Nubia was home to one of the world’s oldest and most dynamic religions. The pantheon of Kush boasts dozens of gods and goddesses, many of which were Nubian in origin.

map by Gargaristan and Augustin Holl

The Mobility Imperative by Augustin Holl pg 104-114. The Land of Houlouf: Genesis of a Chadic Polity by Augustin Holl pg 14-18)

Emergent Complexity and Political Economy of the Houlouf Polity in North Central Africa by A. Holl pg 675-676, The Land of Houlouf: Genesis of a Chadic Polity by Augustin Holl pg 42-43)

Emergent Complexity and Political Economy of the Houlouf Polity in North Central Africa by A. Holl 676-678)

The Land of Houlouf: Genesis of a Chadic Polity by Augustin Holl pg 165, 213, 223-225, 233

The Land of Houlouf: Genesis of a Chadic Polity by Augustin Holl pg 710-711)

Du Lac Tchad à La Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 126)

The Land of Houlouf: Genesis of a Chadic Polity by Augustin Holl pg 139)

The Land of Houlouf: Genesis of a Chadic Polity by Augustin Holl pg 690-693)

The Land of Houlouf: Genesis of a Chadic Polity by Augustin Holl pg 226)

From House Societies to States by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia pg 231-232,

Aspects of African Archaeology: Papers from the 10th Congress pg 589

History of the First Twelve Years by R. Palmer pg 49)

The Land of Houlouf: Genesis of a Chadic Polity by Augustin Holl pg 225-6, A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures pg 531)

‘Kotoko’ by N. Levtzion pg 278, in; The Encyclopaedia of Islam edited by Sir H. A. R. Gibb,

Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab Settlements by Augustin Holl pg 14-23, 389-394

The Land of Houlouf: Genesis of a Chadic Polity by Augustin Holl pg 711-712)

The Land of Houlouf: Genesis of a Chadic Polity by Augustin Holl pg 254)

Emergent Complexity and Political Economy of the Houlouf Polity in North Central Africa by A. Holl pg 685)

Narrative of Travels and Discoveries in Northern and Central Africa by Dixon Denham pg 10-21, 27-29)

Emergent Complexity and Political Economy of the Houlouf Polity in North Central Africa by A. Holl pg 700-701)

Sahara and Sudan, Volume 3 by Gustav Nachtigal pg 508-538)

Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab Settlements by Augustin Holl pg 24-25

Really enjoyed the relationship to geography and location in this one. Also want to say how much I appreciate having such great photos for each article. They're always interesting! Thanks for another great article!