A social history of the Lamu city-state (1370-1885)

Journal of African cities chapter 5

Situated off the eastern coast of Kenya, the old city of Lamu, with its narrow alleys, old mosques and coral-stone houses with white-washed façades, is the quintessential Swahili city.

Lamu was a Janus-faced city, mediating economic and social interactions between the African mainland and the Indian Ocean world. It was poised at the interface of land and sea, and served to link local, regional and transnational economies and cultural spheres.

Its dynamic social institutions created a unique from of government characteristic of the Swahili coast, that was however only preserved in Lamu throughout the turbulent political history of the Indian ocean world.

This article outlines the social history of Lamu, from the establishment of the city-state in the 14th century, to its formal colonization in 1885.

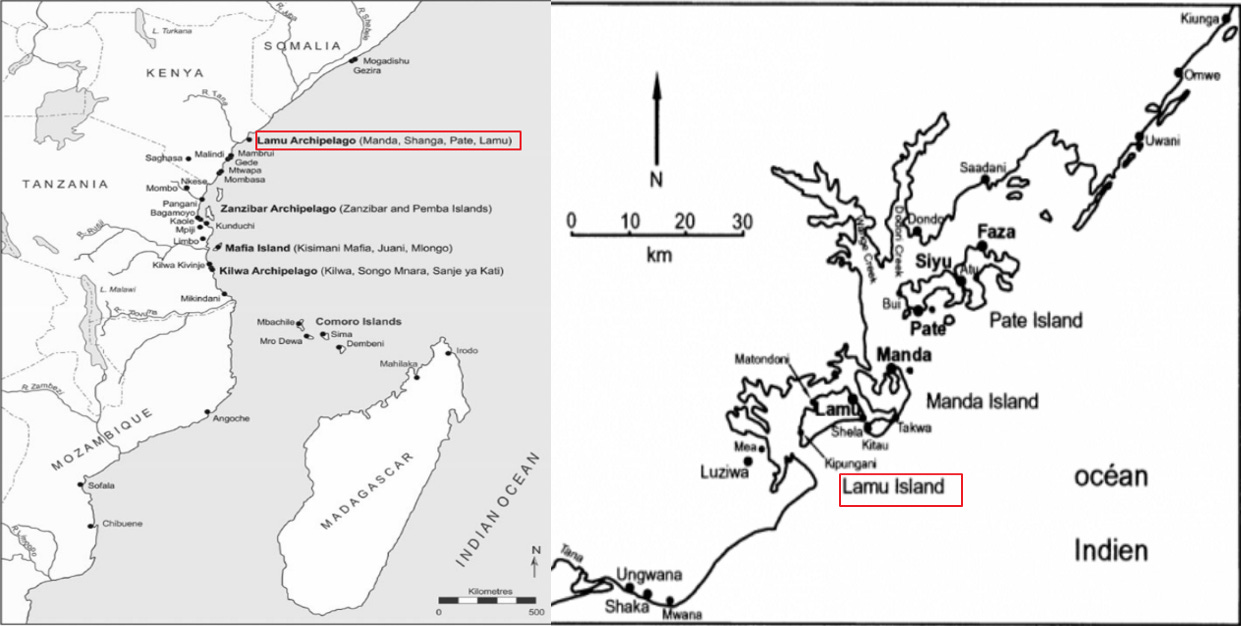

Map showing the location of Lamu island in its archipelago along the coast of Kenya

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early history of Lamu archipelago to the rise of the Manda and Ozi confederations (8th-15th century)

The Lamu archipelago is made up of three islands Pate, Manda and Lamu. The island of Pate was home to the cities of; Pate, Faza, Shanga and Siyu, the island Manda hosted the cities of Manda and Takwa, while Lamu island had only the city of Lamu. The archipelago was settled by the mid 1st millennium during the early expansion of Bantu-speakers of the Sabaki subgroup along the east Africa coast, among whom were groups that Swahili speakers. Prior to the emergence of Lamu, some of the the oldest Swahili urban settlements emerged at Shanga on Pate island and Manda in the 8th century.1

The ruins of Shanga in particular, have the best-preserved stratigraphy in eastern Africa. They reveal the gradual evolution of the Swahili urban society at the turn of the 2nd millennium, from the use of timber and daub to the use of coral stone, the increased participation in maritime trade, the emergence of political institutions, the construction of monumental architecture, and the adoption of Islam.2

While the urban settlement at Lamu was likely established around the 14th century based on an inscription found on the Pwani mosque dated to 1370, it doesn't frequently appear among the Swahili cities mentioned in external accounts before the 15th century --unlike Kilwa, Mogadishu and Malindi which were more actively engaged in maritime trade. There is a brief mention of a qadi from Lamu who met Al-Maqrizi in Mecca in 1441.3 But the apparent invisibility shouldn't be mistaken for its relative insignificance, because dozens of urban settlements within and near the Lamu archipelago emerged between the 12th and 15th century, including Siyu and Faza (on Pate island), as well as; Ungwana, Mwana and Shaka (on the immediate hinterland just south of the Lamu island) and several other ruined towns mostly populated by farmers and fishers less engaged in long-distance trade.4

By the 16th century, two major polities in the form of confederations had emerged on the Lamu archipelago and its immediate hinterland. The city-state of Manda controlled most of the other city-states on the archipelago including Lamu and Pate, while the hinterland city-states were controlled by the sultanate of Ozi whose capital was either at Ungwana or Mwana. Both confederations were ruled by "shirazi" dynasties, a term which is derived from the fictive genealogy made by autochthonous east-African coastal groups who constitute the "Swahili par excellence", in contrast to foreign immigrants who came later such as Hadrami (Yemenis) and Omanis (Arabs) as well as the various groups from the mainland. 5

The manipulation of identity is a frequent phenomenon in the Swahili world, because established lineage groups in the cities constantly redefine themselves according to interactions and competition with immigrant groups. In a society where wealth is a source of authority and prestige, "foreigners" from the hinterland and the Indian ocean could achieve high status by integrating the kinship of their patron, or by enriching themselves through trade.6 This dynamic became especially critical in Lamu's social relations after the the reorientations of population movements in the Indian ocean world after the coming of the Portuguese.

The Portuguese arrival was initially catastrophic to most of the Swahili cities, especially the leaders of the large political confederations such as Mombasa, Kilwa and Ungwana which were repeatedly sacked and looted. Thus, after witnessing the sack of Ungwana in 1506, the sovereign of Lamu quickly sent "tribute" of 600 mithqals of gold and provisions for the Portuguese captain Tristao da Cunha, and received a flag to prove his allegiance. But the early Portuguese hold over the coast proved to be ephemeral and they withdrew southwards to Mozambique island shortly after their puppet in Kilwa had been deposed in 1512.7

Elite tomb and house in the ruins of Shanga

Ruins of an elite house at Ungwana

Ruins of a Mosque at Mwana

The ‘republican’ government of Lamu and the city-states’ economy (16th century)

Lamu was described in Portuguese accounts from the mid-16th century as a sprawling city with stone buildings and a busy port frequented by large commercial vessels with sewn hulls. Like other Swahili city-states, the political system of Lamu was directed by an assembly of representatives of patrician lineage groups, and an elected head of government. The titles of "King" and "Queen" as used in external sources for the different leaders of Lamu were therefore not accurate descriptors for the political power held by the ruler.8

The political and social life of Lamu was governed as a "republic" according to a dual principle that divided the city into spatial and social halves, constituting two factions (mikao) named Zena and Suudi, that comprised several different clans made up of patricians (Waungwana), lower social classes (wazalia) and foreigners (wageni). These clans were themselves led by an elected leader (mzee) who together constituted a council (Yumbe), which inturn chose the mwenye mui as a revolving office between the two factions.9 The factious nature of Lamu's politics involved the use of many legitimating devices through the ritualized maintenance of antagonisms to unite groups of diverse origins and integrate foreigners whose military and commercial alliances were needed during internal contests of power.10

The political factions of Lamu were also spatially divided, a description that is provided in the 18th century but had gradually formed over the centuries.11 The city comprised two quarters named; Mkomani and Langoni, with the majority of households in Mkomani belonging to the Waungwana, while Langoni was inhabited by the descendants of immigrants including coastal groups (eg the Hadrami and Comorians) and groups from the mainland (eg Bajun, Pokomo and Mijikenda). For the Waungwana of Mkomani, the Langoni inhabitants, including the Hadrami sharifs, lacked political respectability and did not have the right to intervene in the public affairs of the city. These social distinctions were however more fluid in practice and anyone could eventually become part of the Waungwana through accumulation of wealth and forging of kinship ties.12

Like its peers in the archipelago, Lamu’s main exports were mostly derived from the hinterland, they included ivory, mangrove timber, ambergris, civet, candlewax, copal, as well as ropes and straw-mat sails used in shipbuilding and repair. The city’s economic exchanges are based on personal ties because each trader is sponsored by his Swahili counterpart residing in the house of his host and ties of friendship and kinship are created. The same is true with the partners on the hinterland such as the Pokomo and Bajun , who were involved in kinship ties and clientelism with the Swahili elites.13

The subsistence of the city-states in the Lamu archipelago, especially Lamu with its poor soils, was based mainly on the agricultural production of their continental hinterland. The lands were developed in common under the direction of a town-based overseer (jumbe ya wakulima), according to a mode of production which was based on the collaboration with continental groups14. In Lamu, this fostered an economic and political alliance with the hinterland town of Uziwa/Luziwa, whose rulers established a symbiotic relationship with the rulers of Lamu. The city's main export of ivory and its agricultural supplies were provided by Luziwa, while the latter received imported products from Lamu in exchange, following a common pattern utilized by other Swahili cities. Lamu's political regalia, especially the siwa ivory horn, is also said to have come from Luziwa.15

17th century Siwa Lamu museum, Kenya

Ruined house showing doorways made of carved coral, and niches. Shela, Lamu, Kenya, 16th century,

patricians Waungwana) sitting in state in a richly decorated reception room in Lamu Town, 1884, National Library of Scotland

The Political history of Lamu from the 16th-17th century

Lamu was ruled by a ‘Queen’ in the mid 16th century who, like the ruler of Malindi, had protected the beleaguered Portuguese against the alliance forged between Mombasa, Pate and the Ottomans during their attempt at breaking Portuguese hold of the Swahili coast in 1546-1554. After the defeat of the Ottomans whose armies had looted and sacked Lamu during the war, its queen was rewarded for the protection by granting her merchants and ships greater freedom of movement. The decision to protect the Portuguese was however, likely driven by an internal political struggles in Lamu and the meteoric rise of the Pate city-state, since the Queen was later deposed between 1571-1585 by an obscure ruler described as a usurper.16

This usurper was named Bwana Bashira, he served as the 'ruler' of Lamu just before the arrival of the Ottoman corsair Ali Bey during the latter's interest in the Swahili coast in 1585-6 and 1588-9. Ali Bey was unlike his predecessors acting entirely in private capacity, and managed to gain the allegiance of many Swahili cities through threats and diplomacy, obtaining tribute and soldiers from each city, as well as detaining the resident Portuguese settlers. While Bwana Bashira was initially reluctant to submit to Ali Bey's forces, he was later compelled to do so by the ruler of Pate to avoid war.17

In response to Ali Bey's actions, the Portuguese sent an expedition which sacked the neighboring city of Faza in 1587 for allying with the Ottomans, and Bwana Bashira fled to the mainland at the town of Luziwa. The Queen whom he had deposed takes the opportunity to regain her position after affirming her alliance with the Portuguese. This process in which the political interests of Lamu and the Portuguese became entangled during periods of internal contests in Lamu would also leads to the creation of pro and anti-Portuguese factions based on evolving political fault lines.18

Ali Bey's ships arrived on the coast a second time in 1588, and several cities including Mombasa and Pate formed an alliance of convenience with him, against the Portuguese who then sent a large fleet in response. After Ali Bey's unexpected defeat caused by the appearance of the enigmatic Zimba forces from the mainland, the Portuguese proceeded to Lamu where Bwana Bashira had reinstalled himself, and they executed him for delivering Portuguese settlers to Ali Bey in 1586. They also invaded Manda city which later fell into permanent decline, and they supported the ‘ruler’ of Pate against the local faction that had invited Ali bey whose leaders they executed, but they couldn't control Luziwa, whose 'ruler' Bwana Zahidi only signed a treaty with them in 1637.19

Despite the Portuguese alliance antagonism with Pate, it was the Lamu archipelago that would became the major pole of attraction on the Swahili coast during the early 17th century. The Portuguese were also integrated into the trade relationships of the Swahili, especially in Pate where they augmented the preexisting ivory trade between the city and the mainland groups, especially the Bajuni-swahili, the Pokomo and the Oromo, that was conducted in the market town of Dondo on the mainland.20

Ruins of an elite residence in Pate

The rise of Pate and its relationship with Lamu in the 17th-18th century

The “rulers” of Pate consolidated military alliances between these mainland groups, as well as with the incoming Hadrami sharifs, inorder to elevate Pate's main Swahili ruling clan —the Nabahani dynasty21— .This created a political structure in Pate that was significantly more centralized than its neighbors in the archipelago including Lamu, Manda and Siyu, which were eventually subsumed. The 18th century was thus a period of renewed prosperity for Pate, and its dependencies in the Lamu archipelago as attested by elaborate coral construction, detailed plasterwork in mosques and homes, and voluminous imported porcelain.

Groups of Hadrami sharif families arrived on the Swahili coast in the context of religious and intellectual activities. They were especially attracted to the Pate's prosperity were they were mostly concentrated, and are first mentioned in the 16th century when a 'ruler' of Pate invited the family of the 'saint' Abu Bala bin Salim to ritually intercede against the Portuguese. They were specialists in theology and law, and were sought by Swahili sovereigns to serve as advisers, and in establishing diplomatic or commercial relations with the Muslim world. As sharifs (who claimed to be descendants of the Prophet), they were also considered intercessors and mediators who could attract divine protection over the community of believers. The Hadrami families, along with the Barawi families (northern Swahili speakers from Brava) whom they arrived with, were credited locally with a cultural renewal and the transformation of the archipelago's social order through the introduction of more orthodox Islamic principles.22

Like all foreign immigrants that came to the cities, the Hadrami sharifs and the Barawi were quickly integrated into Swahili society within a few generations. Although undoubtedly influential, they had remained relatively few in number and were quickly Swahilized; being acculturated to the language and social structure of the city-states. Swahili patricians seeking to elevate the prestige of their lineages with an additional Sharif lineage entered into matrimonial alliances with some of the most prestigious families (especially of the Alawiyya tariqa), creating new dynastic clans that are attested at different points in the history of Zanzibar, Grande Comore and Kilwa, although not at Lamu itself.23

Over the course of the 17th century, the city-state of Pate remained the preeminent power of the Lamu archipelago, heading a confederation of city-states that repeatedly rebelled against the Portuguese and eventually sought alliances with the Omanis of Muscat to expel the Portuguese from Mombasa in 1698. Lamu remained under the suzerainty of Pate during this period, but the exact nature of its subordination is ambiguous beyond the typical matrimonial alliances and kinship networks between both city's dynastic families.24

Lamu continued under Pate's suzerainty until the early 18th century when it rebelled during a period of internal strife in Pate especially in 1727-8, and again during the reign Bwana Tamu (d. 1762) and the civil war following his reign, but Pate re-imposed its authority over on Lamu by the time of its ruler Bwana Fumo Madi (1777-1809).25

Lamu was both the partial cause and beneficiary of Pate's decline in the late 17th century. The city grew significantly in size due to increased alliances with mainland groups some of whom moved to the island, and eventually reached an estimated population of 15,000-21,000 by the late 19th century. The growing significance of Lamu on the archipelago is illustrated by brief mentions in the chronicle of Pate when two of its rulers in the 18th century are said to have lived in Lamu, and made extensive use of its port which later outcompeted Pate's.26

Lamu beachfront, early 20th century

The rise of Lamu, decline of Pate and the Oman period on the Swahili coast.

The stability of Pate during the long reign of its ruler Fumo Madi led him to reassert his suzerainty over Lamu, but the council of Lamu refused to submit to the cereal tribute that the Pate sovereign wanted to impose on them. The tensions between Pate and Lamu were accentuated following the death of Fumo Madi, and the conflict rose between the most powerful candidates for Pate’s throne ; Fumoluti Kipunga and Ahmad bin Sheikh, with the former supported by the Suudi faction of Lamu, while the latter was supported by the Zena faction of Lamu, as well as the Mazrui clan of Mombasa, and the Bajuni of the hinterland.

One of the main causes of Lamu's resistance was its desire to retain the traditional system of land use between the island and the hinterland that was based on clientelism and kinship, against the more intensive form of land use and production of coercive nature favored by Pate and Mombasa, who were considered “devourers of forced labor”. After a period of skirmishing, the battle between the competing alliances took place in 1813-1814 within the walls of Lamu and the village of Shela, where the armies of the Suudi leader Bwana Zahidi Ngumi decisively defeated the Pate coalition led by Ahmad.27

The consequences of the battle of Shela are decisive in the history of the region since Lamu would later ask the sultan of Oman, Sayyid Said al-Busaidi, for military aid to guard against a reprisal from Pate and the Mazrui. Sultan Said responded favorably and dispatched a garrison and a governor, thus opening the beginning of Busaidi suzerainty over the Lamu archipelago. The Oman ascendance on the east African coast greatly reified the internal economic and social realities of the Swahili city-states including Lamu. 28

Pillar minaret of Mnara mosque, Shela Town, Lamu Island built in the 1820s

Sultan Said dispatched a governor named Muhammad b Nâsir b Sayf al-Ma’walî who was was appointed as the “wali” of Lamu, assisted by a garrison that built and settled in a fort in the city.29 But it wasn't until 1824 that the sultan was in control of the Lamu archipelago and repeated rebellions by deposed elites meant that Lamu itself wasn't firmly under Omani control until 1856. Even then, the urban council was only in theory under the Sultans' tutelage via the liwali, but in practice, little effective control was feasible, and the liwali could never be distinguished from the local elites by whom he was surrounded. The council of Lamu therefore mostly continued to meet and govern the affairs of the city.30

The ascendance of Lamu attracted more people from the coast, and like in Pate, led to a consolidation of legitimacy by established patricians against the new immigrants. Its within the framework of the political re-compositions which followed the battle of Shela and the establishment of the Sultan of Oman in Zanzibar, that the prominent Waungwana of Lamu begun to adopt fictitious Sharifan and Oman origins.31

The increased trade augmented the prominence of the Waungwana, the guardians of normative coastal civilization, whose wealth and political power came to characterize the urban character of Lamu. The Waungwana's material possessions such as silk cloths, Chinese porcelain and furniture, their possession of large stone houses with courtyards and zidakas, the number of their dependents and their taste for intellectual activities, were the most visible markers of their high social position. This is contrasted against the lower classes and recent settlers such as the poor Hadrami and Comorians who immigrated in the 19th century and were despised by the Waungwana elite because of their petty trade typical of the peasant class (maskin). Lamu’s Waungwana of early 20th century still kept an image of the Hadrami immigrants as people who only wore a loincloth at the waist (kikoi) and had no shoes or headgear.32

This ambivalent attitude towards "foreigners" was based on established prerogatives on the integration of new immigrant groups. The migration into Lamu of hinterland groups such as the Pokomo and Bajun in the 17th century, and other Swahili eg from Manda and Takwa in the 17th and 18th century, further contributed to the social distinction of the Waungwana who refused to grant these groups full citizenship and considered them to be foreigners/guests (wangeni).33

The typical stone house of the Waungwana of Lamu, exemplifies developments in domestic architecture which followed traditions established in the earlier centuries. The two or three-storey house was entered through a covered alcove or porch (daka) with built-in stone benches (baraza) flanking the entryway providing spaces for socialization, with heavy wooden doors that mark the transition into the interior courtyard (kiwanda) that leads into sequences of rooms. These include the reception room (sabule), inner vestibule (tekani), and the innermost room (ndani) whose rear wall was highly decorated, with multiple tiers of elaborately arched plaster niches (zidaka).34

exterior and interior of the ‘Swahili house museum’ an 18th century Waungwana-type residence in Lamu that was restored recently.

interior of an 18th century mansion of a Waungwana in Lamu, 1884. National Library of Scotland

House in Lamu with zidaka niches, elite chairs and intricately carved door35

As mentioned earlier however, the social distinction between the waungwana and the other classes was not easily discernible in Lamu, and the consumption practices of those living in less elaborate houses, and outside the city were often similar to those living in the stone houses. The Comorians for example, were looked upto as teachers despite being considered wageni, and intermingled with some of the waungwana.36 The waungwana’s power was afterall, a moving equilibrium, with a continuous negotiation of the terms by which social status could be attributed.37 As observed elsewhere across the Swahili coast “The dualist model was an ideal in the minds of the ruling elites rather than a reflection of reality. The so-called city dichotomy was a 'classic stereotype' that 'masked and distorted a more complex and nuanced reality”38

Despite being regarded with contempt by the waungwana, the lower class Hadrami of Lamu supported the Omani elites and their governors in Lamu inorder to grow their petty trade and accumulate enough wealth to rival many of the waungwana, a strategy that was also followed by their Comorian peers. This was likely achieved partly through the growth in the plantation economy, which involved the coercive systems of production that the waungwana of Lamu had opposed.39

This led to further transformations in Swahili identity in the mid-19th century which resulted largely from the desire of the traditional elites to maintain their rank in the social hierarchy both vis-à-vis the new immigrants from Oman and Yemen and vis-à-vis the increasing continental arrivals. Its during the 19th century that the bantu-derived uungwana denoting civilization, was replaced by ustaarabu, meaning Arab-like, reflecting new terminologies introduced during the contests between the established Waungwana and the incoming Omani elites, especially following the influx of the more elite Alawiyya tariqa (brotherhood).40

Importantly, the social alliance between the Omani and the Alawi Hadrami for religious legitimacy greatly enhanced the intellectual traditions of Lamu, especially with the founding of the Riyadha Mosque and Islamic school whose students included not just Waungwana but also ‘foreign’ groups including Somali, Oromo, Bajuni and Pokomo and Comorians that had been been previously excluded.41 However, when the traditional socio-economic structures of the townspeople were threatened, their attitudes towards the Alwai's position in education changed and caused conflicts with the Waungwana who questioned their religious doctrine.42

Following the expansion of imperial interests on the east African coast during the late 19th century, the island of Lamu, and the rest of the northern Swahili coast was taken over by the British in 1885.

the 'Al-Alfiyya' of Ibn Malik, Copied by a Somali scribe named Shārū b. Uthmān b. Abī Bakr al-Sūmālī, in 1858, at the Riyadha Mosque of Lamu.

Modern Lamu

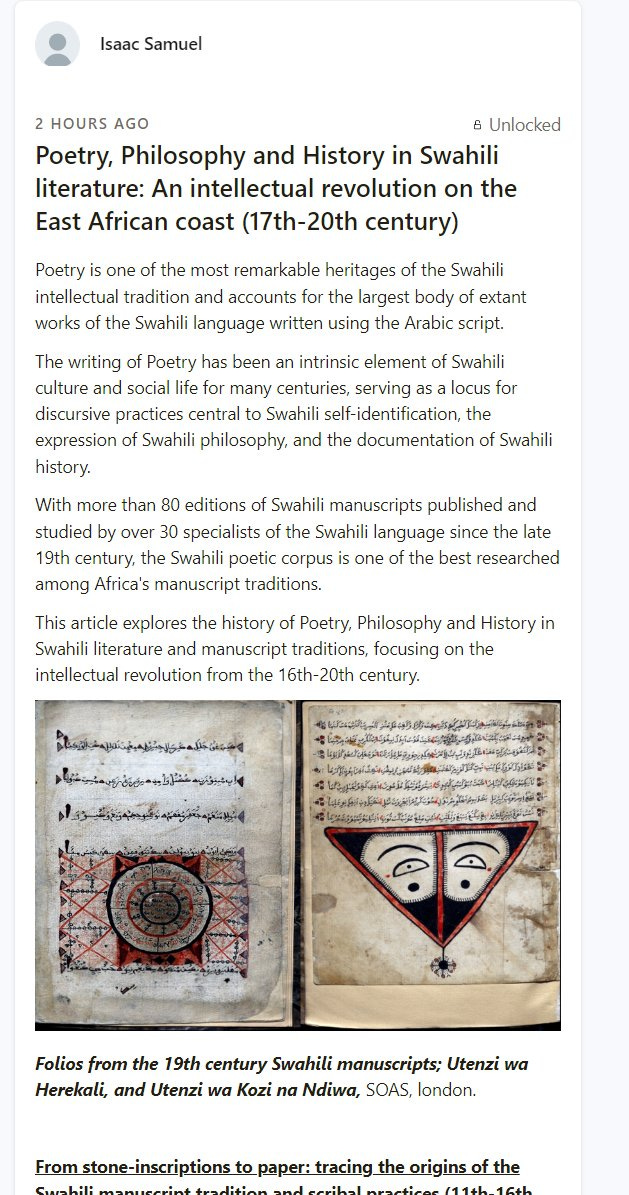

The Swahili world underwent an intellectual revolution beginning in the 16th century when local scholars begun composing various works of Poetry, Philosophy, History and Astronomy. Read about it here;

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette pg 156-162

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette pg 214-218

East African Travelers and Traders in the indian ocean by Thomas Vernet

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 45-46)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 48-56)

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 33-34

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 69-70)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 104)

The battle of Shela by Randall L. Pouwels pg 366-367, 372

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 400-2)

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 45-46

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 520-521)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 75-77, 17, 527)

The battle of Shela by Randall L. Pouwels pg 371

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg pg 32, 44-45 Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet 548, 118)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 91)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 98- 100)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 105)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 111-115, 118)

Reflections on Historiography and PreNineteenth-Century History from the Pate “Chronicles” by Randall L. Pouwels pg 281

Reflections on Historiography and PreNineteenth-Century History from the Pate “Chronicles” by Randall L. Pouwels pg 264-265

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 39-43

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 164-166, Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 50

Reflections on Historiography and PreNineteenth-Century History from the Pate “Chronicles” by Randall L. Pouwels pg 275, Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 331-334

The Pate Chronicle by Marina Tolmacheva pg 179-181)

The battle of Shela by RL Pouwels, pg 371, Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 97-98

The battle of Shela by RL Pouwels, pg 374-375)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 490-491)

Trade and empire in muscat by Rheda Backer pg 84-97

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 98-100, 106-108

The Sacred Meadows by El zein, pg 51-54, Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 110-112

The Sacred Meadows by El zein, pg 88)

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 566, 569)

The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette pg 506-509

from Chinese Porcelain and Muslim Port Cities by Sandy Prita Meier

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 140-141

The battle of Shela by RL Pouwels, pg 382

Les cités - États swahili de l'archipel de Lamu by Thomas Vernet pg 555-6, The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette pg 510

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 113-115, Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar by A. Sheriff pg 70-72, 229

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 72-73

Localising Islamic knowledge by Anne K. Bang, The Swahili World by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette pg 559-563

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 161