African cities in the 19th century: cosmopolitan urban spaces between three worlds.

When the German adventurer Gerhard Rohlfs visited the city of Ibadan in 1867, he described it as “one of the greatest cities of the interior of Africa” with “endlessly long and wide streets made up of trading stalls.” However, unlike many of the West African cities he had encountered which were centuries old, Ibadan was only about as old as the 36-year-old explorer, yet it quickly surpassed its peers to be counted among the largest cities on the continent by the end of the century.1

Originally founded as an army camp in 1829, what was initially a small town grew rapidly into a sprawling city with an estimated 100,000 inhabitants2 living in large enclosed rectangular courtyards organized on principles of common descent rather than centralized kingship. Every community from across the Yoruba-speaking world and beyond converged on the cosmopolitan city, including the Hausa and Nupe from the north, the Igbo from the east, the Edo from the old city of Benin to the west, as well as Afro-Brazilians from the coast and European missionaries.

To most visitors, the city of Ibadan represented a complex phenomenon, with its labyrinthine physical layout and a large heterogeneous population comprised of traders, craftsmen, and farmers. During the colonial period, Ibadan attracted epithets such as the ‘Black Metropolis’ and ‘the largest city in Black Africa,’ and was considered the largest city in Nigeria until the late 1950s when it was ultimately surpassed by the country’s capital.3

Illustrations of a Yoruba Compound and the city of Ibadan as seen from the mission house, ca. 1877, Anna Hinderer.

People walking down the streets, Ibadan, Nigeria, early 20th century. Shutterstock.

At the close of the 19th century, there were more than a dozen cities in Africa whose population exceeded 100,000 inhabitants.4 While the majority of these large cities such as Cairo, Tunis, Fez, and Kano were of significant antiquity, some of them were of relatively recent foundation but they quickly surpassed their ancient counterparts in both size and importance.

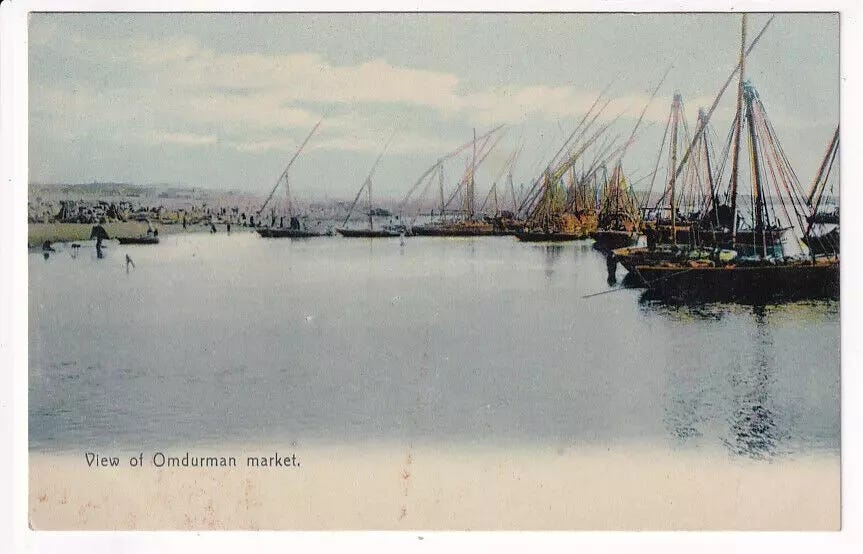

At the confluence of the Blue and White Nile in Sudan, the urban settlement at Omdurman rapidly grew from a collection of hamlets to a large city during the last decade of the 19th century. Founded as the capital of the Mahdist state around 1885, the city housed an estimated 120-150,000 people who included many of the social groups of Sudan, living alongside different groups from West Africa, the Maghreb, and the Mediterranean world.

According to a description of the city by a visitor in 1887, “The inhabitants of Omdurman are a conglomeration of every race and nationality in the Sudan: Fellata, Takruris, natives of Bornu, Wadai, Borgo, and Darfur ; Sudanese from the Sawakin districts, and from Massawah; Bazeh, Dinka, Shilluk, Kara, Janghe, Nuba, Berta, and Masalit; Arabs of every tribe; inhabitants of Beni Shangul, and of Gezireh; Egyptians, Abyssinians, Turks, Mecca Arabs, Syrians, Indians, Europeans, and Jews.”5

Khalifa's house and mosque square, ca. 1930, Omdurman. MAA, Cambridge.

View of Omdurman market. early 20th century.

Market in Omdurman, ca. 1930. MAA, Cambridge.

The heterogeneous concourse of people who flocked to the cities of Ibadan and Omdurman was characteristic of many of the large cities that emerged in 19th century Africa, such as Abeokuta, Sokoto, and the East African city of Zanzibar.

Initially a small town in the shadow of its more prosperous neighbors, Zanzibar in the 19th century became a cosmopolitan locus of economic and cultural interchanges, stitching together Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas. The city was synonymous with the ‘exotic’ in world imagination —the sound of the word Zanzibar itself seemed to epitomize mysterious otherness.

“Ethnic panorama” of Zanzibar. (Left to Right), Sultan Khalifa and Prince Abdullah, ca. 1936, Getty Images; Swahili Hadjis from Zanzibar in Jedda, ca, 1884, NMWV; Arabs and a dhow in Zanzibar, ca. 1950, Zanzibar Museum; Indian women in sarees, ca. 1930, Quai Branly.

Regarded by later colonial officials as the “Paris of East Africa,” Zanzibar was a melting pot of multiple cultures from across the Indian Ocean world, as described in this account from 1905:

“The bulk of the Zanzibar population (apart from the ruling Arabs) consists of representatives of all the tribes of East Africa, intermingled with an Asiatic element. The native classes are spoken of as Swahilis, and the descendants of the early settlers of the Island of Zanzibar are called Wahadimu. Banyans, Khojahs, Borahs, Hindoos, Parsees, Goanese, possess the trade of the island, while Goanese run the European stores and provide the cooks and clerks in European houses. The town swarms with beachcombers, guide-boys, carriers, and camel drivers from Beluchistan [Pakistan], gold and silver workers from Ceylon; Persians, Greeks, Egyptians, Levantines, Japanese, Somalis, Creoles, Indians, and Arabs of all descriptions, making a teeming throng of life, industry, and idleness.”6

The social history of Zanzibar and the origins of its diverse population are the subject of my latest Patreon article, please subscribe to read more about it here:

Zanzibar in the early 20th century.

Gerhard Rohlfs in Yorubaland by Elisabeth de Veer and Ann O'Hear

Seventeen years in the Yoruba country. Memorials of Anna Hinderer by Anna Hinderer pg 20

The city of Ibadan by P. C. Lloyd

for older estimates of global urban population sizes throughout history, see: 3000 Years of Urban Growth by Tertius Chandler, Gerald Fox, pg 196-216, for Kano, see: Hausaland Or Fifteen Hundred Miles Through the Central Soudan by Charles Henry Robinson pg 113.

The Formation of the Sudanese Mahdist State by Kim Searcy pg 95- 118, A Sketch of the Early History of Omdurman by F Rehfisch. Ten years' captivity in the Mahdi's camp, 1882-1892 pg 283

Zanzibar in Contemporary Times: A Short History of the Southern East in the Nineteenth Century by Robert Nunez Lyne