African-Ottoman borderlands during the early modern period: stories from the frontier.

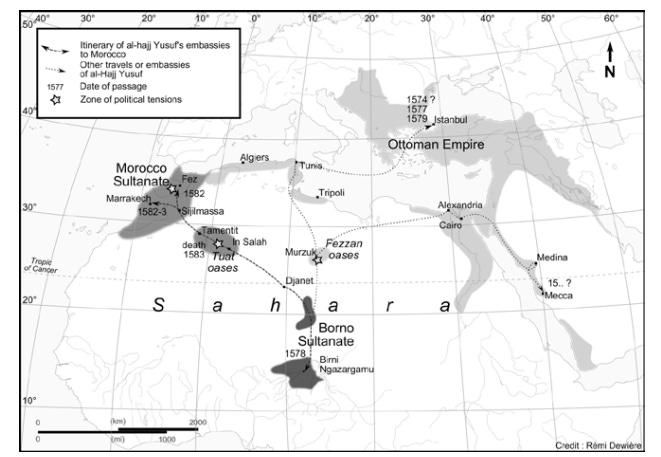

In 1574, the first of two embassies from the kingdom of Bornu in the Lake Chad basin arrived at the Ottoman sultan’s court in Istanbul, seeking, among other aims, to delineate the frontier between the two powers in the region of Fezzan (in Libya).

The Ottomans agreed to most of the requests of the Bornu embassy except handing over a fortress in the Fezzan, which was previously ruled by the Ulad Muhammad, a dynasty of Moroccan origin who were vassals of Bornu.1

The Bornu ruler at the time, Mai Idris Alooma, was therefore compelled to enter into an alliance of convenience with his Moroccan counterpart, Ahmad al-Mansur, following the dispatch of an embassy to Marrakesh between 1581 and 1583. By 1585, the Ottoman garrison in Fezzan was massacred, and the former rulers returned from their exile with Bornu’s support, re-establishing their base at Murzuq.2

Itineraries of the Bornu embassies to Istanbul and Morocco. Map by Rémi Dewière

The Ulads would continue depending on Bornu for military aid and resisting the Ottomans until a compromise was reached around 1626, when Turkish forces were withdrawn, and the hereditary authority of the Ulads was recognized.3

But Ottoman control remained precarious for most of the 17th century. On several occasions, rebellious Fezzani leaders took refuge in Bornu, often in response to attempts by the pashas based at Tripoli to install a garrison at Marzuq. It wasn’t until the early 18th century that the pashas succeeded in imposing their authority over the Fezzan, severing its dependency on Bornu.4

Bornu’s cultural influence in the Fezzan persisted well into the 19th century, when the German traveller Gustav Nachtigal found many “specific reminders” of Bornu’s presence in the region: “numerous gardens, squares and wells still today bear names in Kanuri, the language of Kanem and Bornu.”5

The fortress of Murzuq in the Fezzan region of Libya.

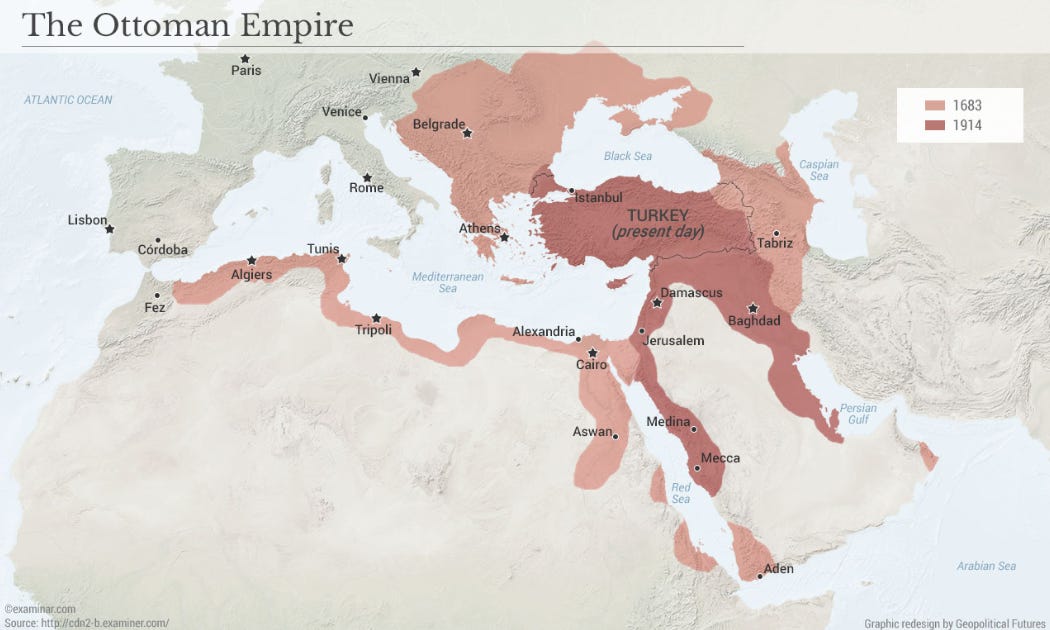

While the modern understanding of borders relies largely on relatively recent concepts of territorial sovereignty and international law, the frontiers of pre-modern states were fluid and frequently contested, making ancient boundaries more ambiguous than what is often shown in historical maps.

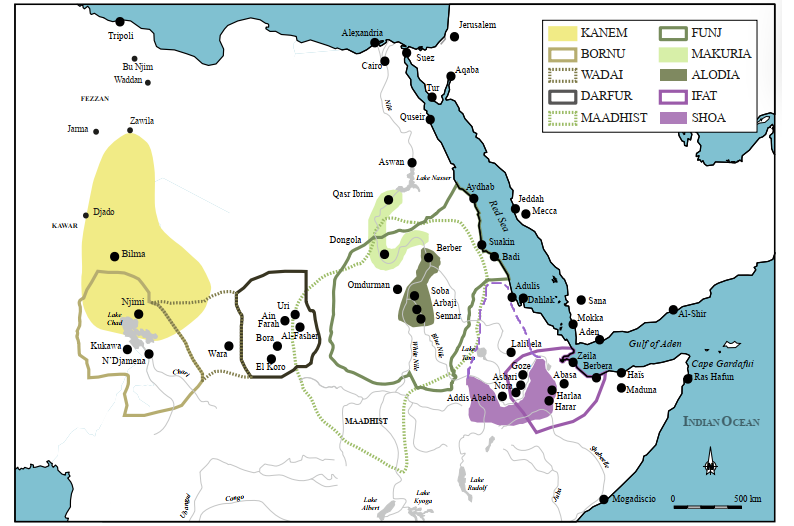

In Africa, the authority of the Ottomans and African kingdoms like Bornu, Sennar, and Ethiopia, gradually petered out along an open frontier extending from the central Sahara to the southern Red Sea coast, leaving the intervening space under the control of local rulers who might pay nominal allegiance to one power or another.

The Ottoman Empire Map by G. Friedman

Some of the kingdoms of North-East Africa. Map by S. Pradines, modified by author

In 1555, the Ottomans created the eyalet (province) of Habeş on the Red Sea coast of Africa, whose capital was established at Suakin (in Sudan) and included the port town of Massawa (Eritrea). Its first governor was Özdemir Pasha, who also established Ottoman presence in lower Nubia at Ibrim (in Egypt).

In the 20 years after the establishment of the eyalet of Habeş, the Ottomans launched six attacks into the mainland, which were ultimately routed by the Ethiopian armies, and Özdemir Pasha was killed in 1560. Another attempt in 1578 was crushed by the Ethiopians, who defeated Özdemir’s successor, paša Ahmed, forcing a retreat to the coast.6

In the 1560s, the Ottomans occupied the fort of Qasr Ibrim in lower Nubia (southern Egypt), which had been largely vacated after the collapse of the Christian Nubian kingdom.7 By 1577, they moved their armies south, intending to conquer the Funj kingdom of Sennar in Sudan. In 1584, the Ottoman army approached the city of Dongola in Sudan with many armed boats, but the invading force was routed by the armies of Sennar.8

Following this string of disasters, increasing military and financial problems closer to home forced the Ottomans to abandon their ambitions for expansion in Africa.

Administration was left to the kaşif (civilian officials of various grades, usually associated with tax collection), who were supported by a small garrison. The Janissaries posted to the Habeş and Nubia were left to maintain themselves through intermarriage and began to identify increasingly closely with local, rather than Ottoman, interests.9

The cathedral ruins at Qasr Ibrim. image from Wikimedia Commons.

Fortress of Qasr Ibrim. ca. 1850

The Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi, who visited Ibrim in 1672, describes it as a semi-autonomous town of a few thousand under the leadership of a kaşif, and notes that “all the local inhabitants are dark complexioned.” He also visited the coastal town of Massawa, which attracted ships from across the Indian Ocean world, and was described as “the seat of the pasha of Habesh”. Its Inhabitants were “all swarthy and black-skinned” and included a small community of Banyans (Indian traders).10

Nearly a century later, the Scottish traveler James Bruce, who visited Massawa in 1769, mentioned that it was under the control of local rulers known as the Belowee (Bäläw; a Beja group), who took the title “Naybe of Masuah”. The janissaries left by the Ottomans had, through “marrying the women of the country,” become “subject to the influence of the Naybe.”11

At Qasr Ibrim in 1813, the Swiss traveler Johann Burckhardt found that the garrisons of Janissaries (apparently of Bosnian origin) had intermarried locally among the Nubians. He mentions that the descendants of these unions “have long forgotten their native language” and were “independent of the [Ottoman] governors of Nubia”, but were instead ruled by their own agas (military officials).12

In these frontier regions, power was more or less entirely devolved to local rulers or agents, who were subjected to the vicissitudes of local politics and economic relations with neighbouring African kingdoms.

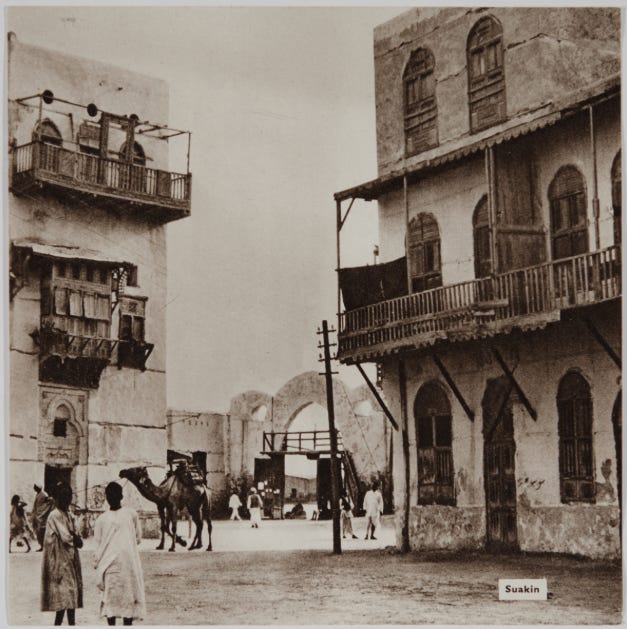

This is especially evident in the history of Suakin, an island city on the Red Sea coast of Sudan, which was formerly the seat of the Ottoman province of Habes between 1550-1670, but remained under the control of local rulers known as the Ḥaḍāriba.

The Ḥaḍāriba of Suakin had ruled the island since the late Middle Ages, when the city attracted merchants from across the Indian Ocean world, and was visited by the famous globe-trotter Ibn Battuta. They briefly exercised political and commercial influence over parts of the Red Sea coast, but later fell under the orbit of the kingdom of Sennar and the Ottomans during the 16th century.

One enthusiastic Portuguese chronicler who visited Suakin in 1541 compared it to Lisbon: “so dense that there is no corner without a building … All the city is an island and all the island is a city”

A later account from 1814 found that the small Turkish garrison had been acculturated into the local society: “many of them assert that their forefathers were natives of Diarbekr and Mosul; but the present race have the African features and manners, and are in no respect to be distinguished from the Hadherebe (ie, Ḥaḍāriba).”

The history of Suakin is the subject of my latest Patreon article. Please subscribe to read about it here and support this newsletter:

Street scene, Suakin, Sudan. ca. 1938. MAA Cambridge.

Mai Idris of Bornu and the Ottoman Turks by BG Martin, Du Lac Tchad à la Mecque : le Sultanat du Borno et son monde ( XVI - XVIIo siècle ) by Rémi Dewière pg 32-33

A struggle for Sahara: Idrīs ibn ‘Alī’s embassy to Aḥmad al-Manṣūr in the context of Borno-Morocco-Ottoman relations, 1577-1583 By Rémi Dewière

Libya, Chad, and the Central Sahara, by John Wright, pg 46

The Cambridge History of Africa: 1600-1790, Volume 4, pg 128-129, Sahara and Sudan, Volume 1 by Gustav Nachtigal, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, pg 153-158

Sahara and Sudan, Volume 1 by Gustav Nachtigal, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, pg 150

The Frontiers of the Ottoman World, edited by A.C.S. Peacock, pg 227-8, 375, The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century by Richard Pankhurst, pg 269-270)

The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia: Pagans, Christians, and Muslims Along the Middle Nile by Derek A. Welsby, pg 254

The Ottomans and the Funj sultanate in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by A.C.S. Peacock, pg 97

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by Geoff Emberling, Bruce Williams, pg 881

Ottoman Explorations of the Nile: Evliya Çelebi’s Map of the Nile and The Nile Journeys in the Book of Travels (Seyahatname) by Robert Dankoff, et al., pg 241-243, 315-318.

Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile by James Bruce

Travels in Nubia By Johann Ludwig Burckhardt pg 134-135

Extremely interesting !

Nice work

Thank you