African paintings, Manuscript illuminations and miniatures; a visual legacy of African history on canvas, paper and walls

a look at African aesthetics through history

Africa is home to some of the world’s oldest and most diverse artistic traditions, from the distinctive textile patterns across virtually every African society to its unique sculptures and engravings

But while many of these are well known symbols of African culture worldwide, little is known about Africa's vibrant painting and manuscript illustration tradition, this is mostly because of painting's association with "High Culture" (High Art) from which African painting is often excluded

In this article, I'll look at the history of African painting and manuscript illustrations that were rendered on three surfaces; Walls, Paper (or parchment) and Canvas (or cloth)

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

Wall paintings; murals and frescos

Painting in ancient and medieval Nubia

Kerman wall painting (2500BC-1550BC)

The kingdoms of the middle Nile region have some of the most robust painting traditions in the world. Wall painting in this region begun in the kingdom of Kerma during early 2nd millennium BC whose antecedents are to be traced back to the cave paintings A-group chiefdom of the forth millennium1

The most elaborate paintings are dated to the classic Kerma period between 1650 and 1550BC that include the polychrome scenes in the mortuary shrines of the Kerma kings and on the walls of the Defuffa temples depicting stars, deities, fishing scenes, hunting scenes, Nilotic fauna (including giraffes) and large lions in a way that art historian Robert Bianchi writes "The depictions invite comparison with the earliest depictions of animals in Nubia, particularly on rock art"

While few photos of the Kerma paintings are accessible, there's one depicting cattle and giraffes from mortuary temple K XI2 and a low relief figure of a large lion made using faience tiles and set in the eastern deffufa temple of Kerma during the classic Kerma era, giving us a look at the painting traditions of Kerma

paintings of giraffes and cattle from the KXI mortuary temple, 18th century BC (at kerma, sudan)

lion inlay from the eastern deffufa temple, 1700BC, (at the boston museum)

Napatan wall painting (8th-4th century BC)

The wall painting traditions of Kush continued into its resurgence as a powerful state during the “Naptan Era” in the 8th century BC when its capital was at Napata and its rulers were buried in the royal cemetery of el-kurru,

While many of the Napatan-era temples, monuments, statues, palaces and houses were often richly decorated with painted scenes, the only paintings that survive were those in the burial chambers and vestibules of the royal tombs esp. the two tombs of queen Qalhata3 and king Tanwetamani4 both built by the latter who also commissioned the paintings

The former tomb was the best preserved and seemingly most lavishly painted featuring scenes describing the queen's path to the afterlife, the ceiling is painted with a delicate star field (first two photos below) , Tanwetamani's tomb is also richly painted depicting him with the typical kushite cap crown (last photo).

queen Qalhata’s tomb paintings, 7th century BC, (at el-kurru in sudan)

queen Qalhata’s tomb paintings, 7th century BC, (at el-kurru in sudan)

Tanwetamani's tomb paintings, 7th century BC, (at el-kurru sudan)

Christian Nubian paintings (6th to 14th century AD)

The period between the 6th and 14th century witnessed the emergence of a distinctive art culture in the christian nubian kingdom of Makura, with its capital at Old Dongola, this art adorned the walls of cathedrals, monasteries, palaces and other buildings in the kingdom, most famous of these collections were the hundreds of paintings recovered from the cathedral of Faras5, the Kom H monastery at Old Dongola6 , and the church of Banganarti7

The artistic center of Makuria was at Old Dongola, its capital, from which the kingdom’s iconographic models and stylistic trends were exported across other regional cities such as Faras

Nubian art is described by art historian "resolutely local style" characterized by rounded figures. an elongation of the silhouettes and the specific design of the eyes and nose, paintings are often multicolored and have a rich chromatic range8, its is however to be located just as much within the larger Eastern Christian art with its byzantine themes

The original themes in Nubian and Ethiopian art are described by Martens-Czarnecka who in her comparisons of both writes that; "the Nubian and Ethiopian painters endeavor to depict "the objective reality of the subject, in accordance with their knowledge or their belief, rather than the 'visual impression that emerges from it"9

The technique used for executing the majority of the Nubian murals was tempera, pigments were sourced locally, the primary colors were yellow, red, black, white and gray. A composition was sketched first in yellow ochre with a thin brush, then the contours of the figures, vertical lines of the robes, etc. 10

nativity mural from faras cathedral, 10th century, sudan national museum

Wall painting of a dance scene from kom h with old nubian inscriptions, 10th-13th century,

Ethiopian wall paintings

From Aksumite paintings through the Zagwe and early Solomonic paintings

Aksum was a powerful state controlling much of the northern horn of Africa and parts of the southern coasts of the red sea between the 3rd and 10th century AD afterwhich the region was controlled by the Zagwe kingdom from the 11th century which later fell to the "Solomonic" empire in the 13th century till the mid 20th century.

The northern horn region , like Nubia, had a much older rock art tradition that continued well into Aksum's pre-christian era and it was this art tradition that was then transferred to other mediums such as building walls, canvas, cloth and paper although the distinctive art style that came to be known as Ethiopian art was largely developed in the mid 1st millennium after Aksum's official conversion to Christianity

While few datable Aksumite paintings survive, there are a number of churches and monasteries from the late Aksumite era that probably preserve original Aksumite paintings eg the paintings on the ceiling of Abune Yemata Guh, the church of Abraha-wa-Atsbaha and Mika’el Debra Selam11 .

In general, Ethiopian wall paintings were often made by trained painters, likely using old pattern books to prepare their utensils: brush, paints and dyes. Painters use locally produced pigments, primarily the colors yellow, red, black and white12

Some of the painters from this period are known by name notably Fre seyon the primary painter of the workshop of a circle of painters employed by emperor Zara Yaeqob's court in the 15th century13 and others such as Abuna Mabaa Seyon, however, most Ethiopian painters remained anonymous, a number of wall paintings include names of people who commissioned the paintings or people who are represented in the painted scenes14.

Abreha wa astbaha painting, undated

Abune yemata guh painting, undated

painting of the archangel Michael, from the 13th century, at the waschka mikael church

painting of two angels, likely from the 13th century, at the Genata Maryam Medhane Alem Church

Gondarine painting (17th to late 18th century)

Between the mid16th and late 18th century. The increasing cosmopolitanism of the Ethiopian court with its imperial capital at Gondar led to the inclusion of a number of foreign painting styles into Ethiopia's artistic tradition

For the Gondarine emperors, patronage of the arts was a means of displaying imperial status as the; Starting with the 17th century, the city of Gondar dominated for centuries the art of Ethiopia. The saying "who wishes to paint goes to Gondar"15 well illustrates this preponderance

This artistic epoch is divided into two periods, the first gondarine style beginning around 1655 and flourishing under emperor Yohannes I (r. 1667-8 2) with painters trained at workshops associated with churches and monasteries near the capital who later influenced the art of regional centers such as at the lake Tana monasteries. The second gondarine style, is associated with the patronage of the regent empress Mentewwab and her son the emperor Iyyasu II (r. 1730- 55) "this florid style is distinguished by its heavy modeling of flesh, carefully rendered patterns of imported fabrics, and shaded backgrounds changing from yellow to red or green." this style also later spread to a number of churches in the Tigray region as well16

Gondarine style murals generally depict expanded narrative cycles including realistic details of clothing, furniture, hair styles, and even genre scenes but while realistic details of costumes and accessories are emphasized, Ethiopian painters continued the tradition of older art styles without an indication of lightsource or a shadow indicating continuity with the early solomonic, zagwe, and Aksumite art styles17

Narga Selassie monastery wall paintings in the second gondarine style , an 18th century painting of mary and child with empress mentewab (at the bottom)

painting of the Archangel michael angel leading the faithfuls, 18th century (found at the abovementioned monastery)

African Paintings on other surfaces;

The painted Pottery and stone slabs from the meroitic art of the kingdom of Kush

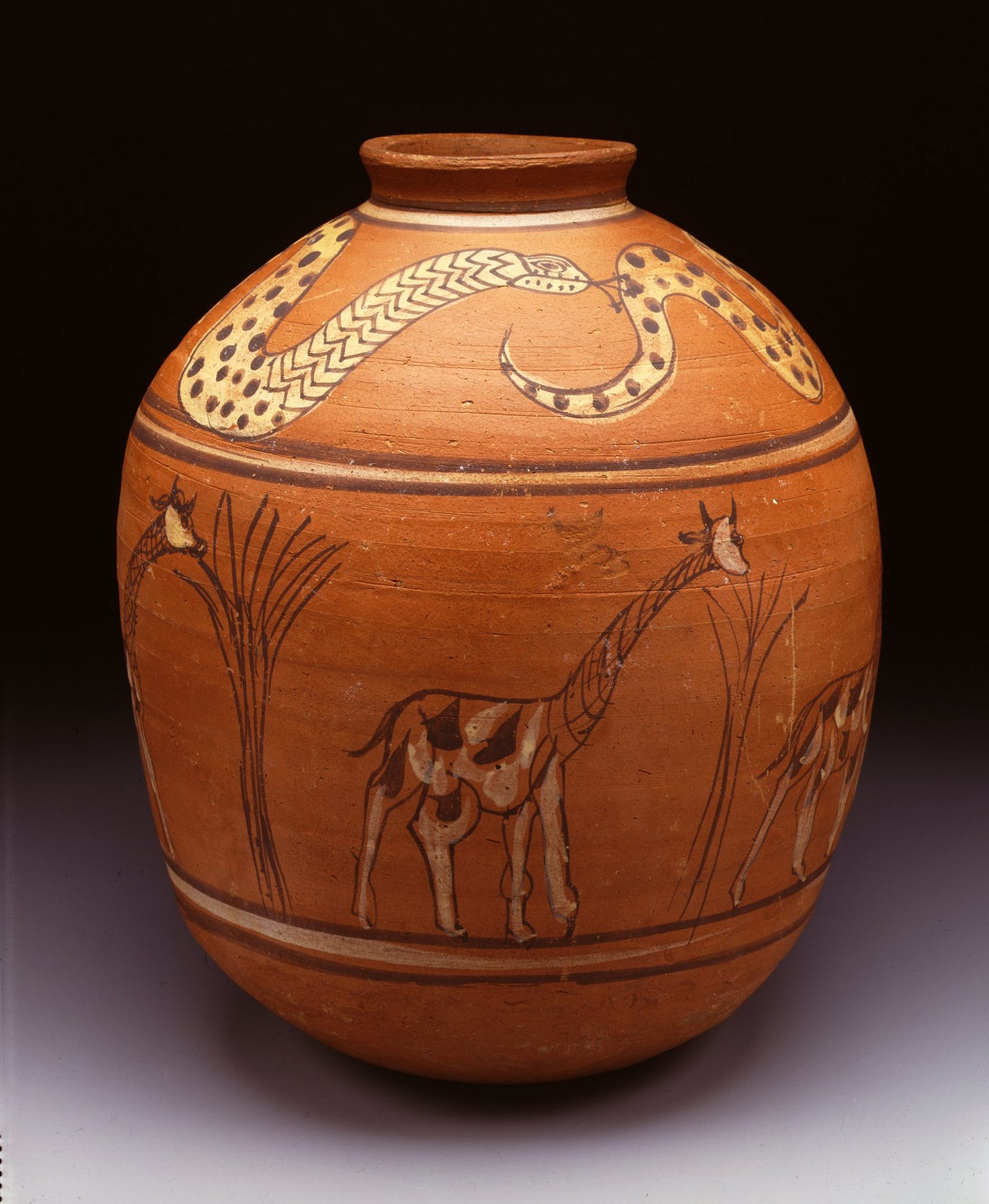

Meroitic pottery (from the Meroitic period when the capital of Kush was at Meroe between the 4th century BC and the 4th century AD) is described as the "the finest achievement of Meroitic art"

Kush's older decorative pottery styles which date back to the aforementioned Kerma kingdom were revived in polychrome pottery painting in the 5th century BC using geometrical, guilloche, and floral motifs, added to this were the new Ptolemaic styles adopted by Kush’s artists in the 3rd century BC; to produce a distinctive painting style employing geometric and floral friezes with a characteristic frieze motif composed of a snake and stars, Nubian fauna, flora and other Kushite themes eg one about ‘the hare, two guinea fowls, and a hyena’ that is derived from an ancient animal fable in Kush from the 4th century BC18

Meroitic pottery's "line drawing style" is described by nubiologist Laszlo Torok; "its decoration structure, iconographical repertory and subsidiary patterns are characterized by a geometrical clarity of the design structure, a striving for sharp definition, and a conspicuous precision of the execution"19

The Meroitic painted Stela are often funerary/mortuary Stelae representing the deceased, they were placed on tombstones or inside their graves, they often depict one or two figures standing beneath a winged sun disk. While the tradition of painting on stone slabs/ stela was revived in the late Meroitic era it had been a feature of Nile valley artistic traditions since the 3rd millennium BC20

Meroitic Painted pottery of giraffe and palm tree, 1st century AD (at the penn museum)

painted pottery depicting a hyena, guinea fowl and a hare; all three are from an ancient nubian folk tale, 1st cent BC-1st century AD (at the oriental institute Chicago)

Stela showing a nubian couple; Meteye (white skirt with a swastika) and Abakharta, 1st cent BC-1st century AD (cairo museum)

funerary stela of a nubian girl found at karanog, 2nd century AD, (penn museum)

Ethiopian paintings on cloth, Canvas and wood

From the Aksumite to the early Solomonic era, the bulk of Ethiopian paintings that survive were rendered on paper/parchment, cloth and on walls, followed in the 15th century by paintings on wood panels known as icons in the form of diptychs, triptychs and polyptychs and by the 16th century, paintings on canvas21

The styles and themes on both of these icons and canvas painting surfaces follow the abovementioned artistic styles; early solomonic, first gondarine and second gondarine, Most icon painters remain anonymous but some notable icon painters from this time include the aforementioned painter Fre Seyon22

Ethiopian painting of "The Last Supper", tempera on linen, 18th century (at the Virginia museum of fine arts)

Elephant hunting, inventoried 1930 (at quai branly museum)

Diptych painting of Mary and the son with various apostles and angels. By fre seyon, late 15th century (at the walter's art museum)

painting on double triptych of the virgin mary and child, 19th cent. (at the brooklyn museum)

African Manuscript illustrations; on miniatures and other decorations in African manuscripts

Nubian manuscript illumination

Nubian illuminations have received limited scholarly attention, but the recent studies of a few fragmentary manuscripts from the cities of Serra east and Qsar ibrm allow for a reconstruction of Nubian illumination, the similarities between the Serra and Qsar Ibrim illumination attest to the presence of a local manuscript production center in Nubia23

The miniature illustrations of bishops, priests and angels on these manuscripts also follow the wider Nubian art styles depicted on wall murals

manuscript with seated bishop giving a sermon from qsar ibrim, 10th-12th century AD (at the british museum)

Illustrated manuscript page from serra east of man sitting cross legged and wearing blue stripped pants, 10th-14th century AD (sudan national museum)

Ethiopian manuscript illumination and miniatures

Ethiopia's manuscript illustration tradition is one of the oldest in the world dating back to the Aksumite kingdom in the mid 1st millennium AD, the Aba Garima gospels, which are two ancient ethiopic gospel books, were dated to between the 4th and 6th centuries AD, making them the oldest illuminated gospels in the world24

Ethiopian manuscripts were illuminated and illustrated following the same styles as their paintings, but also include ornamental interlace, stylized floral, foliate and geometric patterns25, the miniatures depict various figures including apostles and other Christian figures, rulers and patrons, saints and people, flora and fauna, mythical creatures and landscapes, architectural features and buildings, and general representations of contemporary Ethiopian life26

Ethiopian illuminators often worked in monasteries where the skills was passed on from a tutor to their student, by the 15th century two monastic houses had developed their own distinctive styles of illumination; the ewostatewos style and the estifanos style (known as the gunda gunde style27), increasingly, emperors such as Dawit and Zera Yacob patronized the arts and establishing scriptoriums

While most illustrators remained anonymous, a few signed their works eg the scribe Baselyos (also known as the Ground Hornbill Master) active in the 17th century28

miniature from the Garima gospels, a portrait of an apostle, 4th-6th century AD (at abba garima monastery, ethiopia)

miniature of Virgin and Child flanked by the Archangels Michael and Gabriel in the Gunda gunde style, 16th century (at the walters art museum)

illustrations depicting saint walata petros performing various miracles, 1673 from the Gädlä Wälättä hagiography

West African illuminated manuscripts

Much of west Africa's art tradition is primarily rendered on textiles (which will be the subject for a future article) that display a wide range of geometric and floral patterns, its from this artistic tradition that west African manuscript illumination ultimately derives, as art historian Sheila Blair writes on west African illumination "such patterns of diagonals, zigazags and strapwork arranged in rectangular panels are standard on bogolanfini, the "mud-dyed cloths made in mali, traditionally by sewing together narrow strips"29

West African illuminated manuscripts also featured abstract miniature illustrations of the prophet's compound and household (attimes including his wives' houses, sandals, horses, swords), his pulpit and the graves of the prophets and the first two caliphs30

The images are often rendered in highly geometric form with houses indicated as rectangles or circles, walls as colored line bundles and the sandals in abstract form31

Unlike Nubian and Ethiopia illustrations however, the avoidance of depicting sentient beings In west African manuscript miniatures is doubtlessly because of Aniconism in islam

abstract miniatures in a copy of the popular prayerbook 'Dalāʾil al-Khayrāt' written by a scribe in northern ghana, 19th century, (british library)

East African illuminated manuscripts

Eastern africa is home to a wide range of artistic styles and just like west Africa, the majority of its paintings and illustrations were rendered on textiles using a rich array of colors, patterns and designs and while regionally diverse, the illuminations in eastern Africa's manuscript centers were cosmopolitan and adapted as much as they influenced other manuscript centers

The recently published study of an illuminated Harar Qur'an from the 18th century is evidence of this cosmopolitanism, with two way influences between Harar (in Ethiopia), ottoman Egypt, Islamic India and Zanzibar on the Swahili coast32

In east Africa, some of the most notable illuminated manuscripts besides Harar have come from the cities of Mogadishu (Somalia) and Siyu (Kenya)

Siyu in particular flourished in the late 18th and early 19th century as a prominent center of learning, housing several prominent scholars and producing thousands of works that were sold and circulated around the region. Siyu's scribes used locally produced ink33 to render the texts and ornamentation in the classic triad of black, red, and yellow, outlining blank pages in black ink to create a dynamic play of positive and negative space

Siyu's illumination designs derive largely from its local Swahili art, eg the geometric knot motifs on Swahili tombstones, the floral and foliate motifs on Swahili doors and the “Solomon’s knot” that’s common across subsaharan africa34. Siyu's manuscript cultures were partially influenced by similar themes in the mainland cities of Lamu (Kenya) and Mogadishu

Illuminated Qur’an made in the city of Siyu, Kenya by Swahili scribes, 18th-19th century (Lamu Fort Museum)

illuminated Copy of the "Dala'il al-khayrat" (waymarks of benefits) written by a somali scribe, 1899, (at the constant hames collection)

Conclusion

African painters and illustrators were part of the wider African art tradition, African art cultures were thoroughly cosmopolitan incorporating and adopting various art styles, themes and motifs from across different world regions into their own styles but African painters still retained their unique African aesthetics, at times archaizing by bringing back older styles inorder to emphasize the distinctive look that sets them apart from other artistic traditions. African painting is thus an integral part of African history.

I wrote an article on my Patreon about an ancient African Astronomical Observatory discovered in the ruins of Meroe in Sudan, including the illustrations and mathematical equations engraved on its walls

Daily life of the nubians by Robert Steven Bianchi, pg 81

Pastoral states: toward a comparative archaeology of early Kush, page 11,

Royal Cemeteries of Kush, vol. 1: El Kurru by Dows. Dunham, plate 9

Dows. Dunham, plate 18

Pachoras Faras by Stefan Jakobielski

The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Malgorzata Martens-Czarnecka

Banganarti 2003 : The Wall Paintings by Magdalena Łaptaś

La peinture murale copte by du Bourguet

Studies of Sudanese Medieval Wall Paintings from 1963 to the Present - Historiographic Essay by Magdalena M. Wozniak

The wall paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola by Malgorzata Martens-Czarnecka, pg 92,-93

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 222

The Story of Däräsge Maryam By Dorothea McEwan pg 97

African zion by Munro-Hay et al, pg 142

The Story of Däräsge Maryam By Dorothea McEwan pg 97, 98

Major themes in ethiopian painting by Stanislaw Chojnacki, pg 35

African zion by Munro-Hay et al, pg 195

Stanislaw Chojnacki, pg 19

Hellenizing Art in Ancient Nubia by László Török pg 275

László Török, pg 263

Between Two Worlds by László Török, pg 474

Stanislaw Chojnacki, pg 319

The Marian Icons of the Painter Frē Ṣeyon by Marilyn Heldman pg 114

The Oriental Institute 2015–2016 Annual Report. by Gil J. Stein, pgs 140–41

The Garima Gospels by Judith McKenzie, Francis Watson

african zion, pg 63

Secular Themes in Ethiopian Ecclesiastical Manuscripts by Richard Pankhurst

Marilyn Heldman pg 101

Stanislaw Chojnacki, pg 492

The meanings of Timbuktu by Shamil Jeppie et al. pg 69-70)

A Fragment of Paradise by R. Bravmann

The trans saharan book trade by Graziano Krätli et al, pg 236-239

The visual resonances of a Harari Qur’ān by Sana Mirza

Siyu in the 18th and 19th centuries. by J de V Allen

The Siyu Qur’ans by Zulfikar Hirji