Africa's urban past and economy; currencies, population and early industry in pre-colonial African cities.

private land sales, manuscript copyists and textile sales figures.

Africa was a land of cities and vibrant urban cultures, from the ancient cities of the Nubia and the horn of Africa, to the medieval cities along the east African coast, on the plateaus of south east Africa, in the grasslands of west-central Africa, in the forest region of west Africa and more famously; the storied cities of Sahelian west Africa1. Discourses on early African urbanism have now moved beyond the now discredited theories of Africa's lack of urbanism or its supposed introduction by foreigners, these new discourses seek to reconstruct the economies of early African urban settlements, early handicraft industries and Africa’s spatial and scared urban architecture.

African urbanism both conforms to and diverges from the established definition of cities; some African cities were directly founded by royal decree or were associated with centralized authority from the onset; such as Kerma, Aksum, Mogadishu, Kilwa, Great Zimbabwe, Mbanza Kongo, Benin, Kumbi Saleh, Gao, Ngazargamu, Kano and el-Fashir. while other cities were mostly associated with trade, religious power or scholarship, such as Qasr Ibrim, Adulis, Zeila, Sofala, Naletale, Begho, Djenne, Walata and Timbuktu; both of these types of cities were often characterized with monumental architecture; such as such as the palaces, temples and religious buildings in the cities of, Jebel Barkal, Lalibela, Gondar, Pemba, Zanzibar, Danangombe, Loango, Kuba, Ife, Bobo Dioulasso, Chinguetti and Daura. and the city walls2 of Faras, Harar, Shanga, Old Oyo, Segu, Hamdallaye and Zinder.

Inside these African cities were large markets held daily in which transactions were carried out using various currencies most notably coinage that was locally struck in the cities of the kingdom of Aksum, the Swahli cities, Harar (Ethiopia), Nikki (Benin), and the cities of Omdurman and el-Fashir (in Sudan), there was also foreign coinage that was adopted in most of the “middle latitude” African states (all states between Senegal and Ethiopia) and lastly, the ubiquitous cowrie shell currency of the medieval world. African cities were home to several guilds of professional artisans and other types of wage laborers, the former included architects and master-builders, blacksmiths, carpenters, the latter included, dyers, weavers, leather workers, manuscript copyists and illustrators, painters and carvers, and dozens of other minor and trivial commercial activities such as astrologists, wrestlers and prostitutes. The majority of public buildings in African cities were religious buildings and their associated schools; such as temples, churches, mosques and monasteries and the Koranic schools of west Africa, Sudan the horn of Africa and the eastern coast; and the monastic schools of Ethiopia, other public buildings included the public squares of the Comorian cities3 and a few Swahili cities. African cities recognized various forms of private property perhaps the most notable being the land charters and private estates in the cities of the states of Makuria, Ethiopia, Funj, Darfur and Sokoto among others.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Defining African Cities

"the city is a phenomenon which is notoriously difficult to define"4

There have been many attempts at a theoretical definition of what qualifies as a city, the classic definition, which has since been modified and/or contested was that proposed by Gordon childe in which he associates urbanism with centralized states and thus lists the features of a city as; having considerable size, high population density, production of agricultural surpluses, monumental architecture and craft specialization. He also lists others features including; writing systems, state officials, priests and long-distance trade5 . Several of the above listed features have since been contested especially since its possible to have monumental architecture, writing systems and trade without association with centralized political power or lack some of the above yet still live in an urban settlement associated with centralized political authority. But since several of these features overlap frequently, new definitions of cities have only modified Childe's classical categorization rather than radically alter it, these overlapping features for most cities are; craft specialization, agricultural surplus, population density and long-distance trade.

Following these overlapping definitions, discourses on African urbanism have forwarded definitions of African cities including those that fit Childe's classical definition and those that diverge from it. In the former; there are several African societies that existed as city-states; in which an independent state is centered on a city (rather than a state that contains a plurality of several cities) and in which a “city-state culture” thrives; characterized by people of similar language but living in fully autonomous states centered on cities which often compete and war with each other. In Africa, such city-states include the Yoruba city-states (southwestern Nigeria) , the Swahili city-states (Kenya and Tanzania coast), the Hausa city-states (northern Nigeria), the Kotoko city-states (southern chad), the Banaadir city-states (Somalia), the Fante city-states (southern Ghana), among others.6 Added to these cities that fit the classical definition are the "primate cities", these are where the largest urban settlement in the state (kingdom/empire) is the capital city; for example the cities listed in the introduction of this article like Gondar and Benin, such cities formed the bulk of African urban settlements.

lastly some African cities also diverged slightly from the classical definition but are situated firmly within the bounds of it, these cities are defined as "a large and heterogeneous unit of settlement that provides a variety of services and manufactures to a larger hinterland" and their features include specialized labor, high population density and long distance trade, among others. An example of such were the "cities without citadels" and the mobile capitals. Of the “cities without citadels” there are the classical cities of the inland Niger delta and the Senegal river valley, eg Jenne jano which covered over 7 hectares by 300BC growing to 33 ha in the mid 1st millennium, with a surrounding urban cluster of 170 ha and a city wall. Jenne-jeno also had settlement quarters for blacksmiths, potters, weavers, etc before much of the population moved to the better known city of Djenne7. Among the mobile capitals were the katamas of medieval Ethiopia8 and in the interior of East Africa such as the capitals of the Buganda Kingdom9 and the Bunyoro kingdom.

monumental architecture of An african city; the 17th century castles of Gondar, photo from the early 20th century

public buildings of African cities; the bangwe (public square) of Moroni and Grande Comore

Africa’s urban demographics

The cities of Africa varied in population depending on their primary functions; the city-states and primate cities had both permanent and floating populations. The permanent populations were comprised of residents who dwelt within the city for generations and consisted of the city’s oldest lineages, clans and families, while the city’s “floating populations” included traders and caravans, visitors, pilgrims, armies, and the like. As such, the estimated populations of African cities varied in size, the bulk of these estimates are given by archeologists, internal and external written documents, and explorers.

While Africa had a relatively low population density in the past, the settled regions were fairly densely populated, with high population density clusters in the inland Niger delta (central Mali) northern and south-eastern Nigeria, the Ethiopian highlands, the east African coast (from Somalia to Tanzania) and other moderate population clusters in west central Africa (western and southern DRC, Northern Angola), the African great lakes region (central and western Uganda and Rwanda), and south-eastern Africa in Zimbabwe and eastern south Africa. which allowed for the development of cities.

The rate of urbanization in medieval Africa was therefore quite significant, the Mali empire is reported to have had at least four hundred cities/towns (the chronicler used the Arabic word mudun: plural for city) this urbanization compared favorably with contemporaneous kingdoms of the world, and Mansa Musa told al-Umari that he had personally conquered at least 24 of these cities; which at the time included the cities of Timbuktu and Walata10

Population estimates of African cities:

The population estimates for African cities can be grouped into two; the cities established before the 19th century (these estimates rely on both written accounts and archeological estimates); and the cities established during the 19th century (the populations of these can be extrapolated backwards and more reliable estimates from various sources exist)

Of the pre-19th century cities (ie; from antiquity until 1800s); the most populous African cities were Gao and Timbuktu in the 16th century, and Gondar, Katsina, in the 18th century; these four are estimated to have attained a maximum population of 100,000 people during their heyday, with a low estimate of at least 70,000. These cities compare favorably to some of the most populous cities of late medieval Europe and north Africa both in size11 and in population; especially during the 16th century, such as the cities of Florence, Lisbon and Prague (all of which had an estimated 70,000 people) and the city of London (with an estimated 50,000 people), while in north Africa, Tunis and Marakesh had between 50-75,000 people as well12. These comparisons don't take into account the significantly higher population densities in the latter regions which would point to a relatively higher rate of urbanization in Africa at the time, for example, west Africa in the 1700 had an estimated population of 50 million13 which is just over twice France's 20 million people.

overview of the population estimates for the largest African cities before the 19th century

Gao was the capital of the Songhay empire, an unofficial census conducted in the 1580s gave a total of about 100,000 as written in the Tarikh al-fattash14, while the Tarikh al-sudan states that Gao had about 7,626 houses not including the semi-permanent structures giving an estimate of 76,000 permanent residents15 which combined with a floating population of caravan traders would have approached 100,000 people.

Timbuktu was a major commercial and scholarly city in the Mali and Songhay empires, the Tarikh al-fatash estimated it had 150 schools, each enrolling around 50 students, the student population was about 7,500 providing an estimated urban population of 75,00016 not including the floating population of caravan traders which in the 19th century was reported as at times trebling the resident population although by then the city was much smaller17

timbuktu in 1906 seen from the sankore mosque (by edmond fortier)

Katsina was the largest Hausa city in the 18th century prior to the ascendance of Kano, the explorer Heinrich Barth provides an estimate of a maximum of 100,000 inhabitants in the mid 18th century18

Gondar, the capital of the Ethiopian empire during the Gondarine era was estimated to have at least 65,000 inhabitants in the late 18th century when explorer James Bruce visited it, this figure is only for the families resident in the city proper, and doesn't include the armies of the king and the traders. Other estimates by later explorers such as Rosen and Mérab estimated the population to be at about 100,00019, which isn't implausible since population decline had already set in by the time of James Bruce's visit.

Aside from these four largest cities, whose high populations lived in densely packed settlements such as storied buildings which can support a larger number of people in a smaller area, there were less densely packed urban settlements such as Ile-Ife, Benin and Old Oyo where houses were single-storey and compounds were fairly widely spaced, some of these cities extended over 50 sqkm and contained 19sqkm of built-up space, providing a population estimate of around 100,000 for all three at their height in the 14th, 16th and 18th centuries20

The other cities from this period that were significant populous (between 50,000-100,000) include the Kanem capital of Ngazargamu that had around 60,000 to 70,000 people in the 16th century, and the cities of Zaria, Agadez, Djenne and Kano that had around 50,000 people in the 16th century 21

djenne in 1906 with ruins of the mosque at the center (by edmomd fortier)

The next group are the moderately populated cities (between 30,000-50,000) such as the ancient cities of Meroe, Aksum and Old Dongola, the medieval cities of Mombasa, Kilwa, Mogadishu, Mbanza kongo, Loango, Mbanza Soyo, and later cities of Kumasi, Kong, Abomey, Zinder, Kukawa, and dozens of other cities (usually the capitals of kingdoms), estimates for the above populations come from various sources most notably R. Feltcher22, T. Chandler23 and C. kusimba24 .

The rest of African cities include those with populations between 10,000-30,000; which were the vast majority from antiquity to the 19th century, including Jenne-jeno, Kumbi saleh, Adulis, Zeila, Begho, many of the Swahili cities (such as Pate and Siyu), the Benadir cities (such as Merca and Brava) Hausa cities (such as Gobir and Hadejja), the cities of the Zimbabwe plateau (such as Great Zimbabwe and Naletale), the inland Niger cities (such as Segu and Nioro), the central Sudanic cities (such as Logone-birni and Kousseri), the Ethiopian cities (such as Haarla and Ifat) and the capitals of west-central africa (such as Nsheng and Mwibele)

the city of Merca in the early 20th century

ruins of the 14th century city of Great zimbabwe

African Cities of the 19th century

African cities experienced a marked growth in the 19th century, most of the abovementioned cities of the pre-19th century doubled their populations by the middle of the century while other cities finally breached the 100,000 population limit, most notably, Sokoto which had 120,000 people in the early 19th century25, Omdurman which had 250,000 people in the late 19th century26 and Ibadan which had over 100,000 people in the mid 19th century27, among others.

general view of Omdurman in the 1920s

Sustaining African cities: extraction of agricultural surpluses from the hinterland and commercialization of agriculture and land.

The continued existence of cities requires substantial agricultural surplus from the city’s hinterlands for the city-dwellers that are engaged in specialist pursuits. The evidence for such surpluses is present in Africa, most notably were the royal and private estates such as in the Songhay empire which produced between 600-750 tonnes of rice a year that was meant for the consumption of the royal household and personal army all of whom numbered 5-7,000 people28, the royal and private farms around the city of Kano, Mbanza kongo and various swahili cities, such as the city of kilwa, whose poor soils, high population and textile production required intensive trade and interactions with the mainland29 such interactions involved purchases of agricultural surpluses30

While in the “middle latitude” states of Africa such as Ethiopia, Makuria, Sokoto and Darfur, the land grant/charter system allowed for rulers and elites in cities to supply both their extended households and the city’s markets with large agricultural surpluses to support the bulging populations, in Ethiopia this proliferated during the gondarine era in the 18th century31 and in Darfur during the 18th century32 and in Sokoto during the 19th century33 and in Makuria from the 11th to the 14th century34. The estates established by both elites and private entrepreneurs supplied agricultural produce to local markets and the existence of such commercialized agricultural production and land tenure systems led to the growth of a robust land market in the four African states mentioned above with the majority of private land sales confined to their cities.

land charter of Nur al-Din given to him by darfur king Muhammad al-Fadl in 1810AD (from R.S.O Fahey’s land in darfur)

The Currencies of African cities; minting, adoption and exchange of various forms of currencies in African urban commerce

The complexity of African monetary transactions and economies is often underappreciated, African cities were major centers of commerce in both the regional and global contexts this cosmopolitanism required them to utilize a standardized medium of exchange in the form of currencies; as such African cities made use of multiple and complementary coinage and commodity currencies, most notably; the gold, copper and silver coinage in the cities of the kingdom of Aksum35 (such as at Aksum and Adulis), the kingdom of Makuria36 (especially in the cities of Qasr Ibrim and Old Dongola), the Swahili city-states of Kilwa, Shanga, Pemba, Songo mnrara, Tongoni and Zanzibar37, the city-states of Harar and Mogadishu cities in the horn of Africa38, and the kingdom of Nikki39 (in modern benin), and the silver issue of the kingdom of Kanem Bornu in the city of Ngazargamu40 the other form of coinage was the imported Maria Theresa silver coin used across the Sahel and the horn of Africa in the late 18th to early 19th century, but mostly common in the Ethiopian empire.41

Kilwa silver and copper coins of Ali ibn al-Hasan from tanzania dated 10th-11th century (Perkins John, 2015)

silver coins from the mahdiyya and darfur kingdoms in the 19th century sudan (british museum)

The second form of currency was the gold dust and gold bars, common in the empires of the Sahel (Ghana, Mali, Songhai, Massina, Air, Kanem-bornu) and the Asante kingdom, and used in various west African trade networks most notably by the Wangara across various west African cities. it was measured using standardized gold weights; these weights were most present in the upper volta region (in the Asante, Dagomba cities)42, the inland Niger delta (Segu to Jenne) and the Senegambia cities.

The third and perhaps the most ubiquitous currency across africa was the cowrie shell, some were acquired locally especially the nzimbu shells of the west central African kingdoms of Kongo and Loango43 but the majority were imported and were used in virtually all west African, eastern African and some southern African kingdoms from the late first millennium to turn of the 20th century.

lastly were the commodity currencies; primarily cloth and iron. The former became a lucrative trade for the kingdoms of Benin, Kongo and Kuba whose high quality and standardized textiles were in high demand in the surrounding regions, Benin cloth (aso-Ado) was bought and re-exported during the early decades of atlantic commerce to the Akan states in the gold coast44 while Kongo's cloth (libongo) was rexported during the early stages of the atlantic commerce to many of the states of west-central Africa45; and metal currencies included manila, copper ignots, and the later standardized iron bars were used in parts of west Africa.

Many African cities used several currencies concurrently and it was therefor necessary to establish currency exchanges that were fixed depending on the demand and supply of each currency; one such exchange rate was for 40 pices of silver for one pice of gold in the kingdom of makuria especially the city of qasr ibrim46, in mali during the 14th century, one gold coin was exchanged for 1150 cowries in the city of gao 47and several other exchanges such as coin to cowrie, cloth to cowrie, gold dust to cowrie.

12th century painting from Old Dongola showing financial transaction; depicting a man holding a purse giving another man a handful of gold coins (from the Kom H monastery)

The currencies above were primarily used in urban commerce both for internal trade in local markets and for long distance trade; an example of the use of gold dust and gold bars as currency is from an account of a wangara trader named al-Hajji al-Wagari from Timbuktu that sent 2000 ounces in gold bars and 2000 ounces of gold dust in exchange for a large consignment of cloth to be bought in the Moroccan city of Akka in 179048

African currencies international value isn't to be underestimated, as Aksumite coins were found as far as India49 and Kilwa coins were found as far as northern Australia50 and southern Arabia attesting to both the cosmopolitanism of these cities and the value of their currencies, they also travelled significant distances in the African interior; a Kilwa coin was found far inland at great Zimbabwe, it can thus be concluded that African economic transactions especially in African cities were often fully monetized contrary to the misconception that the most common system of exchange was batter.

Handicraft industries in African cities.

Arguably the most common industry in precolonial Africa was textile production. textile production in Africa is first attested in the khartoum neolithic where some spindle whorls were found likely for making wool cloths in the 6th millennium BC51. Cotton cloth was well established in Nubia during the 1st millennium BC, and then in west Africa, the horn of Africa and east Africa by the 1st millennium AD while cloth production was developed independently in west central Africa in the early second millennium AD. In all these African regions, major centers of production and use of cloth were typically the urban settlements. Alot has been written about African cloth production, cloth trade, and the various processes of spinning, weaving, dyeing, embroidering African cloth, but less has been written about the methods of production, the quantities of cloth traded and produced especially in relation to African cities; and the reason for the de-industrialization of Africa's textile manufacturing.

Various African textile producing centers used different looms, whose development and utilization dependently largely on the antiquity of cloth production in a given region.

Varieties of looms in Africa (map from K. Frederick’s Twilight of an industry)

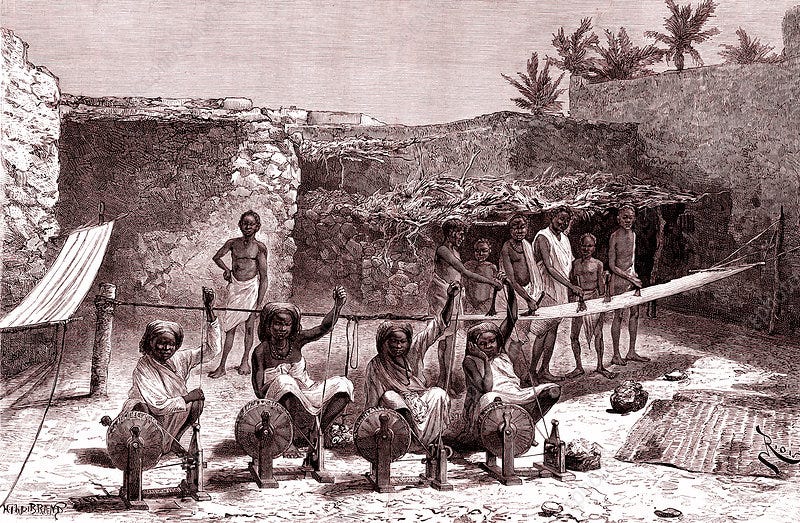

In the horn of Africa, the weavers used treadle looms positioned over pits, along with spinning wheels to speed up the production of yarn (especially in the cities of Mogadishu and Harar).

Cotton spinning somalia 19th century

In west Africa, narrow-band treadle Looms were used, these also had foot pedals that manipulate warp threads and were used alongside the more common vertical looms to produce larger cloths (such as in the cities of Kano, Zaria, Benin) the vertical loom was also used in parts of west central Africa. In eastern Africa, the majority of looms were fixed-heddle ground loom52

Hausa woman weaving on vertical loom

The work of cotton cultivation, spinning, cloth weaving, dyeing and embroidering were done by both women and men in various stages and attimes involved organized textile guilds and private estates for large production, but also involved small-scale domestic production for small quantities. The majority of these processes were confined to cities rather than the countryside as was noted in Benin, Kano, Mogadishu, Zanzibar and Mbanza kongo.

African textile trade; the figures

In terms of quantity, the most significant cloth producers whose figures can be retrieved were the regions of south-western Nigeria, west-central Africa and the Sahelian west africa, such figures include;

In Benin city, at the height of the textile trade in the 17th century, the Dutch purchased 12,641 pieces 1633–34 in another 16,000 pieces of Benin-cloth in 1644–46, and the English bought about 4,000 pieces of Benin-Cloth in the same years, (a standard piece of Benin cloth was about 2 meters by 3 meters) both of these were resold to the gold-coast region (modern Ghana) who then sold them further inland53 this outbound trend from Benin was only a fraction of the internal trade especially between Benin and the Yorubalands and the Hausalands giving us a picture of just how extensive Benin’s textile production was.

Cloth production in west central Africa, while less urban than in west Africa, was nevertheless significant, in 1611, upto 100,000 meters of libongo cloths were exported from Kongo’s eastern provinces into the Portuguese coastal colony of Angola annually and 80,000 meters of Loango's cloth were also exported to the colony of Angola annually as well54. This cloth was evenly split into use both for clothing and as currency and while some of it was purchased by kongo and loango from further inland, most of it was refashioned and standardized in Kongo and Loango itself to maintain its currency value and authenticity using unique geometric patterns

libongo cloth from the kongo kingdom, inventoried in 1659 (Ulmer Museum)

Cloth production in the sahelian belt was also significant, in the 19th century, explorer Heinrich Barth estimated that the city of Kano alone exported over £40,000 worth of cloth annually ($7,000,00 today) which is a significant amount given a population of under 70,000, describing the city's textile industry as thus:

"there is really something grand in this kind of industry, which spreads as far as murzuk, ghat and even tripoli; to the west not only to timbuctu, but in some degree even as far as the shores of the atlantic, to the east all over bornu, and to the south and south east"55

the textile market in the Hausa cities was sophisticated enough to allow for product returns, this was observed by the explorer Hugh clapperton who visited Kano decades before Barth, he described it as thus :

"if a tobe (gown) or turkadee (woman's cloth), purchased here is carried to bornu or any other distant place, without being opened, and is there discovered to be of inferior quality, it is immediately sent back as a matter of course -the name of the dylala, or broker, being written inside every parcel in this case the dylala must find out the seller, who, by the laws of kano, is forthwith obliged to refund the purchase money" 56

Riga and Boubou robes from the hausa cities of northern Nigeria in the 19th century, (from; liverpool and quai branly museum), photo of a fokwe chief wearing a riga (University of Southern California.)

kano in the 1930s (walter mittelholzer)

These processes of cloth production in African cities used both free labor (subsistence and wage) and servile labor. The labor demands of such industries were very large and its no surprise that these aforementioned states banned the exportation of slave labour into the atlantic (Benin in the 16th-17th century, Kongo in the 17th century and Sokoto in the 19th century, among others). Significant cloth production was also noted in the swahili cities of Pate, Kilwa and Sofala and the somali city of Mogadishu where as early as the 14th century, its maqadishu cloth was exported as far as Egypt

Other major African handicraft industries included;

iron production, which was sufficiently developed in the cities of the east African coast as noted by historian C. Kusimba: "Swahili ironworkers were capable of producing high-carbon steel and even cast iron in their bloomeries with over 2.5 percent carbon" these cities also exported iron to the Indian ocean cities in southern Arabia and Southern Asia57, the other notable African urban iron production center was the in the ancient city of Meroe where about 20 tonnes of metal were produced annually in the late 1st millennium BC, which for a population of about 30,000 was very significant; Meroe was therefore a site of a substantial iron industry58

Leatherworks such as sandals, shoes, bags, boots, etc were made locally in significant volumes, most notably in Kano where an estimated 10 million pairs of sandals, leather straps and bags were exported all across west Africa and north Africa especially to morocco where Kano's leather was then re-exported to Europe as "Moroccan leather" which was used in book bindings59 and other major leatherworking cities such as the cities of Zinder and Ngazargamu, the Swahili city of Siyu and Zanzibar, the upper volta cities of of Salaga and Bondouku the western sudan cities of Segu, Timbuktu and several others.

leather boots, shoes and sandals from the Hausa cities of northern Nigeria, inventoried in the mid 19th century (Museum of Applied Arts&Sciences, Australia)

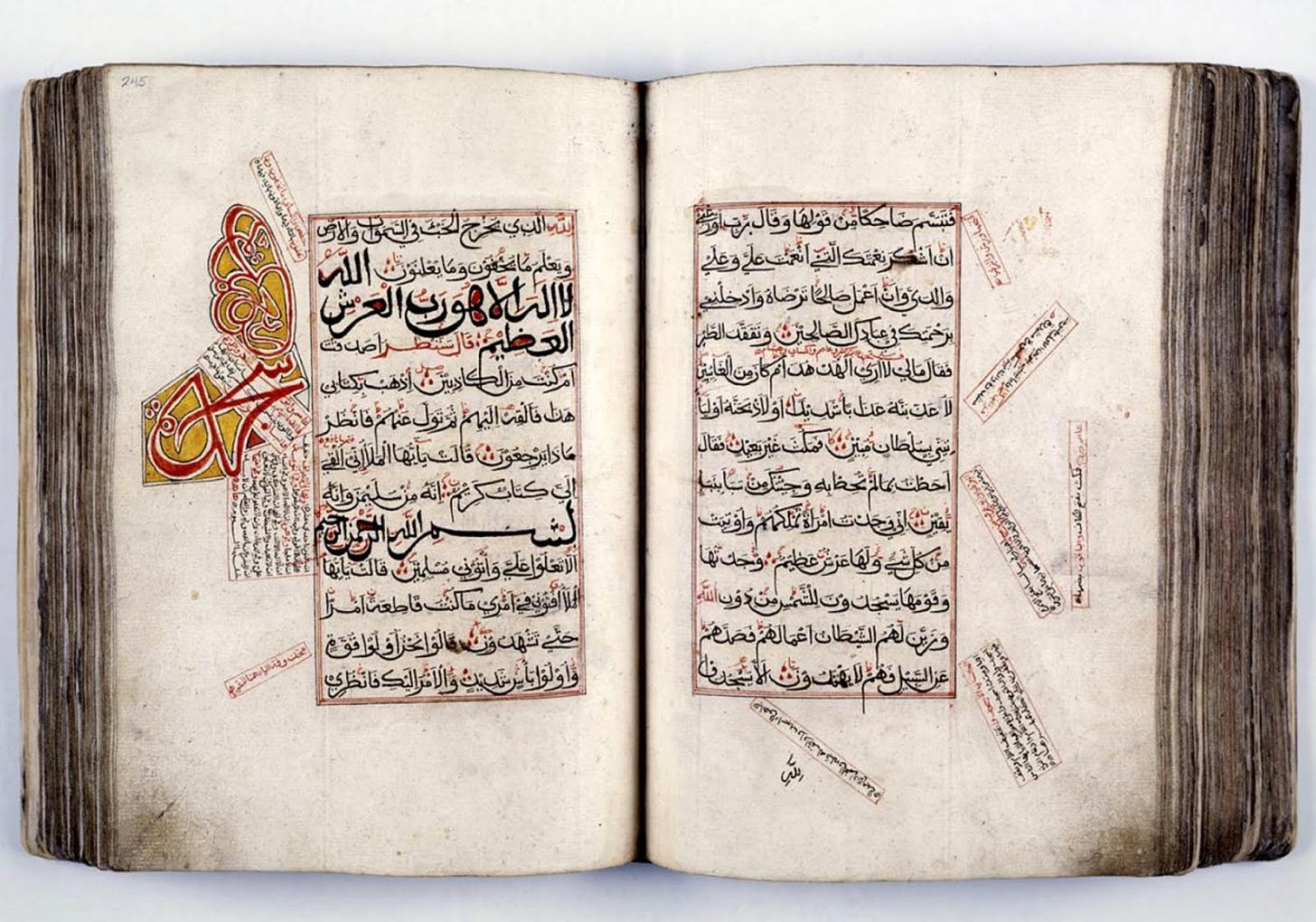

Manuscript copying, book binding and manuscript illumination was perhaps the only African industry exclusively confined to cities, manuscript copying was fairly widespread across much of Africa's “middle latitudes”, along the east african coast and the west central African cities in kongo. African manuscript illumination is attested as early as the 5th century AD at Aksum and later in the mid-second millennium AD at several other cities such as Timbuktu, Jenne, Kano, Ngazargamu, and book binding was present at the cities of Gondar, Mogadishu, Harar, Lamu, Siyu among others. The best documented manuscript copying industry was in Ngazargamu, the capital of Kanem-bornu which was a major center for specialists such as calligraphers and copyists whose beautifully written and illustrated Qur'ans were sold throughout north Africa in the 18th and 19th century at a price of fifty thalers60 and the city of Siyu whose position as a major scholarly center In east Africa rivaling Zanzibar was such that books written and illuminated by Siyu's scholars were sold all across the coast61, one of such books copied was a Quran written by a copyist named Ali al-Siyawi (his nisba meaning he is from siyu)

Quran from the early 19th century, siyu (Fowler Museum)

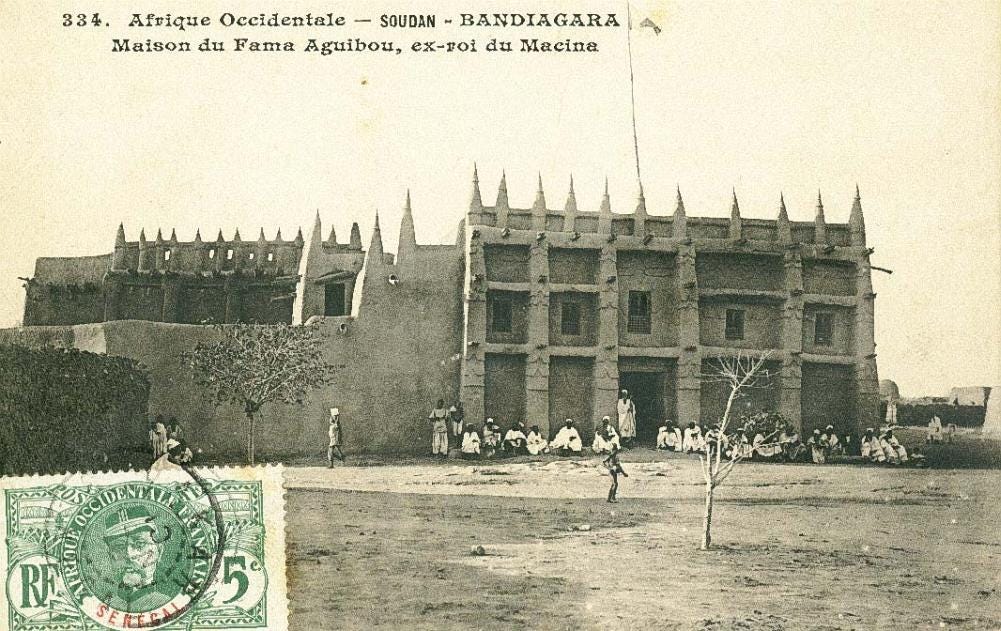

construction ; which involved architects, master-builders and masons guilds such as the Hausa architect Muhammadu Mukhaila Dugura who constructed the Zaria Friday mosque62 and the Djenne mason guilds known for erecting a number of large mansions in the late 19th and early 20th century such as the Bandiagara palace of Aguibu tall, Gbon Coulibaly's house in korhogo and the reconstruction of the 13th century mosque of Djenne, these master builders and architects were likely present since the early first millennium but their activities proliferated during the 19th century especially in the Sokoto empire where urban planning was state policy63

Aguibou tall's house in badiagra buiilt in the 19th century (edmond fortier)

Conclusion

The vibrancy and cosmopolitanism of Africa’s urban past, and the dynamism of pre-colonial African cities are a window into Africa’s economic and social history, African urbanism was central to African state-building, art and architecture, the legacy of which continued well into the colonial and post-independence era, some of Africa’s old cities maintain their prominence into the present day, state capitals such as Mogadishu, Accra and Abuja, commercial emporiums such as Lagos, Mombasa and Kano, religious and pilgrim cities such as Lalibela, Timbuktu and Harar are among dozens of cities whose sacredness and importance continues to attract thousands of visitors. African cities are a salient piece of African history.

A special thanks to all the generous contributors on my patreon and via paypal that keep this blog up, i’m grateful for your generosity.

for more on African history, Free book downloads and ancient African astronomy, subscribe to my Patreon account

The Archaeology of Africa by Bassey Andah et al, pg 21-31

Africa's urban past by D. M. Anderson, pg 36-49

Becoming the Other, Being Oneself by ian walker, pg 97-99

the urban revolution by G. childe, pg2

The Fabric of Cities by Natalie Naomi May, pg 5

A comparative study of thirty city state cultures by Mogens Herman Hansen, pgs 445-533

Sahel by Alisa LaGamma, pg 62

Diversity and dispersal in African urbanism by R. Fletcher, pg8

D. M. Anderson pg 98-106

african dominion by M.A. Gomez pg 127

R. Feltcher, pg 7

3000 Years of Urban Growth by T. Chandler, pg 15, 46

African Population, 1650–2000 by P. Manning

West African Journal of Archaeology - Volumes 5-6 , Page 81

Timbuktu and songhay by J. Hunwick, pg xlix

Social history of Timbuktu by N. Saad, pg 90

Sahara by M. de Villiers, Pg 213

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa vol2 by H Barth, , pg 78,526-7

An Introduction to the History of the Ethiopian Army by R. Pnkhurst, pg 171

Precolonial African cities size and density by C. kusimba, pg 154-157

T. Chandler, pg 47

Settlement area and communication in African towns and cities by R. Fletcher

3000 Years of Urban Growth by T. Chandler

Precolonial African cities size and density by C. kusimba

C. Kusimba, pg 153

Sudanesische Marginalien by F. Kramer, pg 90-101

the city of ibadan by P. C. Lloyd pg 15

J. Hunwick, pg 159

African historical archaeologies by A. M. Reid, pg 110

African civilizations by G. Connah, pg 257

Land and Society in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia by Donald Crummey, pg 166, 109

Land in Dar Fur by R. S. O'Fahey, pg 14

State and Economy in the Sokoto Caliphate by K. S. Chafe pg 80, 87

Medieval Nubia by G. R. Ruffini pgs 42, 202-226

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson, pg 181-193

G. R. Ruffini pg 259, 175-205

currencies of the swahili world by K. Pallaver

The Coinage of Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Italian Somalia by D. Gill, pgs 27-29, 87-88

The Nineteenth-Century Gold 'Mithqal' in West and North Africa by M. Johnson pg 522-553

The Cowrie Currencies of West Africa. Part I by M. Johnson, pg 42

D. Gill, pg 17-19

A New Look at the Akan Gold Weights of West Africa by Hartmut Mollat

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 By J. K. Thornton pg 34

Trade and Politics on the Gold Coast, 1600-1720 by K. Y. Daaku , pg 24

J.K.Thornton pg 14

G. R. Ruffini pg 178-180

Metals and Monies in an Emerging Global Economy by D. O. Flynn, pg 226-228

history of Islam in africa by N. Levtzion pg 103

D. W Phillipson, pg 192)

The Swahili Coast, 2nd to 19th Centuries by G. Freeman, pg 2

Early Khartoum by A. J. Arkell

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Frederick, Katharine, pg 210-213),

Benin and the Europeans by A. F. C. Ryder, pg 93

J.K.Thornton pg 13

An economic history of west africa by A. G. Hopkins, pg 49

Narrative of travels and discoveries… vol2 by H. clapperton , pg 287

Metals and metal-working along the Swahili coast by Bertram B. B. Mapunda

The nubian past by D. Edwards pg 173

Economic History of West Africa by G. O. Ogunremi, Pg 27

narrative of travels and discoveries … vol2 by H. clapperton, pg 161-162

Siyu in the 18th and 19th centuries by J. de V. Allen, pg 18-24

Hausa Urban Art and Its Social Background by F W. Schwerdtfeger, pg 110-113

A geography of jihad by S. Zehnle, pg 131