An African anti-Colonial alliance of convenience: Ethiopia and Sudan in the 19th century

From conflict to co-operation

Among the recurring themes in the historiography of the “scramble for Africa” is the notion that there was no co-operation between African states in the face of the advancing colonial powers. African rulers and their states are often implicated in the advance of European interests due to their supposedly myopic “internecine rivalries” and “tribal hostilities” which were said to have been exploited by the Colonial powers to “divide and conquer”.

Besides the inaccuracies of the anachronism and moralism of hindsight underlying such discourses which disregard African political realities, there are a number of well-documented cases of African states entering into ententes, or “alliances of convenience” against the approaching invaders, while some of these alliances were ephemeral given the pre-existing ideological and political differences between the various African states, a number of them were relatively genuine cooperations between African rulers and were tending towards formal political alliances of solidarity against colonialism. In the last decades of the 19th century, the Ethiopian empire and the Mahdiyya state of Sudan —which had been at war with each other over their own internal interests— entered into an entente against the Italian and British colonial armies.

This article explores the history of Ethiopia and the Mahdiyya in the 19th century until the formation of their anti-colonial pact.

Map of North-eastern africa in the late 19th century showing the Madiyya and Ethiopian empires, as well as the british advance (in red) and the sites of Mahdiyya-Ethiopia conflict (in green).

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The Ethiopian re-unification; From Tewodros and the British to Yohannes’ defeat of Ottoman-Egypt

A century of regionalism in Ethiopia ended in 1855 with the ascension of Tewodros II and the restoration of imperial authority. The empire had since its disintegration in the 1770s, been faced with formidable political challenges, its national institutions had collapsed, provincial nobles had fully eclipsed the royal court and church, just as external powers (ottoman-Egypt and the Europeans) were appearing on the scene. Tewodros’ charismatic character and his ambition to reform and modernize the state institutions, initially won him many victories over the provincial nobles whom he reduced to tributary vassals after a series of battles resulted in him controlling much of central and northern Ethiopia by 1861.1 This allowed him to briefly focus on the foreign threat presented by the expansionist Ottoman-Egypt led by Pasha Muhammad Ali (r. 1805-1848) who had since 1821 colonized much of Sudan and was expanding along the red sea coast; threatening to isolate Ethiopia. Tewodros had faced of with the Ottoman-Egyptians earlier in his career in 1837 and 1848, but once enthroned, he couldn't commit fully to the threat their western presence posed before pacifying a dissenting provincial noble in the region.2 He nevertheless and appreciated the need to modernize his military systems, and attempted to acquire more modern rifles from the european traders within the region such as the French and the British but was frustrated by their alliance with Egypt3. Repeated rebellions by his vassals (including the future emperors; Menelik in Shewa province, Yohannes in Tigray province and Giyorgis in Lasta province) reverted the empire’s earlier centralizing attempts back to the preexisting regionalism and reduced Tewodros’ army from 80,000 to 10,000 soldiers.4 His attempt at forcefully utilizing the disparate European missions within Ethiopia for his modernization efforts in arms and transport, coupled with the detention of foreign envoys in his royal camp, soured his relationship with the British who invaded Ethiopia in 1868, defeating his greatly reduced army at Magdala, looting the region and carrying off some of his relatives.5

Takla Giyorgis (r. 1868-1871) succeeded Tewodros shortly after his demise, the former shored up his imperial legitimacy by restoring Gondar's churches and castles6 and attempted to consolidate his control over the powerful provincial rulers through a proposed alliance with Menelik and through his marriage with Yohannes' sister, but the latter's assertion of his own power in the northern province of Tigray led to a clash between their armies in 1871 in which Yohannes emerged victorious.7 Yohannes IV (1872–89), now emperor of Ethiopia, pursued the imperial unification of the state that had been initiated by his Tewodros but rather than adopting the uncompromising centralization of the latter, he opted for a policy of “controlled regionalism”, which relieved his forces from provincial conflicts that had challenged both of his predecessors, to instead focus on the foreign threats facing Ethiopia, particularly the Ottoman Egyptians who were especially concerning to Yohannes whose powerbase in Tigray was the most vulnerable to a foreign advance from the red sea8.

british expedition camp approaching maqdala (No. 71906, Victoria & Albert Museum)

photographs of Prince Alemayehu, Tewodros’ son who was captured by the British at Maqdala and passed away in England (Royal collection, British Museum)

Yohannes IV's palace in mekelle built in 1882

Yohannes’ war with the Ottoman-Egyptians

Yohannes’ contemporary and ruler of Ottoman-Egypt was Khedive Isma‘il (r. 1863-1879) who was Muhammad Ali’s grandson. He continued Egypt’s development through borrowing extensively from European creditors, he hired European and American military officers, adventurers, and geographers to overhaul the armed forces and administration, and the Red Sea coast upto Somalia became a target for Egyptian expansionism especially following the completion of the suez canal in the late 1860s. In 1865, he increased his interest in the provinces of Sudan subsumed by Pasha Ali in the 1820s, and thus requested and renewed the Ottoman authority over the red-sea ports of Massawa and Suakin which had since reverted to local control. Then, beginning in 1870, after the suez canal was opened, the entire Somali Red Sea coast, from Zeila to Cape Guardafui, was captured by Egyptian military missions, who completed the conquest by capturing Harar in 1875, taking over the historical capital of Ethiopia's old Muslim foe; the Adal empire. By then, Ottoman-Egypt was at the peak of its imperial power, ready to connect the Red Sea with the Sudan and stabilize a whole new empire. But then Egypt collided with Ethiopia.9

Ottoman-Egyptian troops had moved into keren region (in eritrea, just north of Tigray) a few months after Yohannes was crowned in 1871 and had subsequently occupied it. Yohannes had sent envoys to Europeans; France and Britain, requesting them to press Egypt to withdraw but they were reluctant to get involved, and tactically sanctioned the Egyptian advance, with the British Queen Victoria writing to Yohannes that it was her impression the Khedive was only pursuing bandits.10 In 1875, Four Egyptian missions penetrated Ethiopian territory. The first group occupied Harar but didn’t advance further inland, another was delayed on the Somali coast11, but two groups managed to enter the Ethiopian interior; A small force of 400 soldiers, headed by the Swiss general Munzinger, was to reach Menelik’s province of Shewa and bribe him in destroying Yohannes, en-route however, the group was annihilated by in Awsa, its arms and gifts captured12. A second force of 3,000 soldiers set out from the port of Massawa, this force met with Yohannes’ army in Gundet and was virtually wiped out. When the news reached Cairo, Isma‘il tried to suppress the disaster and prepared for a full-scale war.13 Plans by the Khedive to ally with Menelik against Yohannes were thwarted when the former offered some of his troops to increase Yohannes’ imperial army14. The invading force of 50,000 (with 15,000 soldiers), under the command of Ratib Pasha and US confederate general General W. Loring, returned to Eritrea. On March 1876 they were maneuvered out of their fortifications at Gura by Yohannes’s generals led by the general Ras Alula and overwhelmingly defeated, An estimated 14,000 Egyptian soldiers were killed in both battles15, Those who escaped the massacre (including Isma‘il’s son) were taken prisoner and released only after negotiations were conducted and a treaty signed in which the Egyptians agreed not to re-enter the ethiopian highlands. The “well-drilled military machined armed with Remington rifles, Gatling machine-guns and Krupp artillery- the epitome of a modern colonial army” was all but annihilated by Yohannes’ relatively poorly equipped force of just 15,000 fighting men.16

The Egyptians conducted a war of attrition using the services of the warlord Wolde Mikail, forcing Yohannes to send his general Ras Alula to pacify the region and expel the Egyptians, a task which he accomplished from his headquarters at Asmara and forced Wolde to surrender in 187817, but couldn’t fully eject them from their fortifications.18 Negotiations between Yohannes and the Khedive’s envoys continued through the latter’s British officers but reached a stalemate that wasn’t broken until the Mahdist movement in Sudan had overthrown the Egyptian government and threatened to annihilate the Anglo-Egyptian garrisons in Sudan forcing the British to agree to Yohannes’s terms.19 But the vacuum left by the Egyptian retreat was gradually filled by the advance of France and Italy from the Somali coast, who gradually came to control a number of strategic ports along the red sea, restricting the emperor's arms supplies, and keeping him pre-occupied his northern base, while loosening his control over his vassals such as Menelik who had trading with both.20

map of the Ottoman-Egyptian invasion from the red sea regions

Ramifications of the Ethiopian victory: British occupation of Egypt and Ethiopia’s neighbor the Mahdiyya.

The Gura defeat was arguably one of the most important events in the history of modern Egypt , the Ethiopians foiled the Egyptians’ goal of connecting their Red Sea ports to the Sudan, and while the Egyptians had all the resources and international legitimacy in 1876 to build a regional empire, the immediate financial losses caused by the Gura defeat worsened an already deteriorating balance of payments and ushered in the beginning of direct European interference in Egyptian affairs. In 1876 Isma'Il was forced by impending bankruptcy to give his European creditors oversight of his debt service, and to accept an Anglo-French 'dual control' of his current finance, and a series of natural disasters in 1877 and 1878 exacerbated the already dire situation in Egypt and its debt crisis, by 1879, Isami'il was deposed by the Ottoman sultan on European pressure in favour of a puppet Tawfiq, whose regime fell to the Urabi movement that sought to rid Egypt of the foreign domination.21 The Gura defeat had triggered a wave of Egyptian nationalism; leading the veterans of the Khedive’s Ethiopian campaign (such as Ali al-Rubi, Ahmad ‘Abd al-Ghafar, and ‘Ali Fahmi) to join with the nationalist leader Ahmad ‘Urabi (who had witnessed the defeat), to launch the anti-western Urabi revolt with the slogan “Egypt to the Egyptians.”22 The ensuing upheaval and overthrow of Tawfiq’s puppet government instigated a British military invasion and occupation of Egypt in 1882, further loosening the Egyptian control of Sudan which was rapidly falling to the Mahdist movement.23

The Gura victory also altered Yohannes' foreign and domestic policy towards his Muslim neighbors and vassals, while he used a fairly flexible policy during his early rein, including marrying a Muslim woman (who passed on in 1871) and allying with the predominantly Muslim elite of central Ethiopia.24 But this changed the moment Isma‘il's forces set foot on Ethiopian soil and tried to entice local Muslims onto their side. Yohannes’ rallying call to defend Christian Ethiopia was couched in terms of a religious war against invading Muslims, by tapping into the memories of Ethiopia’s wars with the Adal sultanate which in 1529 led to the near-extinguishing of Ethiopia by the Adal armies of Ahmad Gran. As one European witness described it, “It was in fact the first time in centuries that the Abyssinians as a whole responded to a call to protect their land and faith, and the clergy were the most potent instruments of propaganda. The popular movement was such that even Menilek, who the previous year had been intriguing with Munzinger, felt he ought to send his complement of troops.”25, After the victory, Yohannes' policy became less conciliatory towards not just Ottoman-Egypt, but also against his Muslim vassals. After resolving the internal divisions in the Ethiopian orthodox churches by organizing the council of Boru Meda in 1878, Yohannes compelled all Ethiopian Christians to adhere to the official doctrine, and coerced all Muslims and traditionalists within his realm to embrace Christianity, (many of whom had adopted Islam during the regionalism preceding Tewodros’ ascent), and the ensuing resistance forced a number of Muslim elites to flee to Sudan and join the Mahdiyya26. Yohannes had been so fervent on his mission that Menelik (whose political situation in Shewa required him to take a more conciliatory approach27) is said to have asked "will God be pleased if we exterminate our people by forcing them to take Holy communion" to which Yohannes replied "I shall avenge the blood of Ethiopia. It was also by the form of sword and fire that (Ahmad) Gran Islamized Ethiopia, who will if we do not, found and stregthen the faith of Marqos".28 It was these Mahdists that would present the greatest threat to Yohannes’ authority for the reminder of his reign.

A brief history of Sudan before the Mahdiyya

The Funj kingdom and Ethiopia

Much of the Sudanese Nile valley had since the 16th century been dominated by the kingdom of Funj whose capital was at Sennar (near modern Khartoum), the Funj state presided over an essentially feudal government, ruling over dozens of provinces with varying degrees of autonomy and tributary obligation. In 17th century, the Funj were trading extensively with the (Gondarine) empire of Ethiopia, despite a brief period of tense relations in which Ethiopian Emperor Susenyos attempted an invasion of Funj in 1618-19.29By the early 18th century tensions over the borderlands led to the Ethiopian emperor Iyasu II launching an invasion of Funj in 1744 but he was defeated by the armies of the Funj king Badi IV (r. 1724–1762) at Dindar river30. Both iyasu II and Badi IV were coincidentally the last of their respective state's competent rulers, their demise heralded an era of decline in both Ethiopia and Funj as both fell in to a protracted era of disintegration and regionalism that in Funj, would result in the decline of its central government such that when the Ottoman-Egyptian Pasha Muhammad Ali of launched his invasion of Sudan in 1821, the smaller provincial armies didn't pose a formidable military challenge, resulting in Egypt controlling all of Funj's teritories.31

Ottoman-Egypt occupation of Sudan

The period of Ottoman-Egyptian rule, known in Sudan as Turkiyya, was largely resented by the Sudanese who saw the Ottoman-Egyptian administration and its development efforts of exploiting local resources for the treasury, as instruments of oppression and injustice, and alien to most of their traditional religious, moral and cultural concepts32, especially once the Ottoman-Egyptians began to implement their administrative and taxation policies that fundamentally affected the lives of ordinary Sudanese. These taxes were collected by soldiers who were incentivized by their cut to collect more than was required, which itself was already unrealistically high, the most disliked was the saqiya tax, which forced many Sudanese out of the lands that paid the highest taxes near the Nile, and into other professions including trading and mercenary work, but even these evasion efforts were curtailed. A series of tax reforms initiated by Khedive Ismai’l in the 1860s, only exacerbated the problem such that by 1870s, the European administrators whom he’d hired, reported about the deplorable state of the region, writing that because of "the ruin this excessive taxation brought on the country. many were reduced to destitution, others had to emigrate, and so much land went out of cultivation that in 1881, in the province of Berber, there were 1,442 abandoned sakiyes, and in Dongola 613". Tax enforcement became more violent and intrusive during the economic crisis from 1874-1884, such that when a young Nubian Holy-man named Muḥammad Aḥmad started a revolt under the slogan “Kill the Turks and cease to pay taxes!”, his revolution immediately attracted a large following across all sections of society.33

letter from the Mahdī to Gordon dated october 1884 informing the latter of the capture of his forces and warning of his arrival at Omdurman (durham university archives34)

In 1881 , Muḥammad Aḥmad and his second in-command, Abdallāhi defeated several expeditions sent by Rāshid Bey, the Ottoman-Egyptian governor of Fashoda and captured ammunition35, after which Muḥammad Aḥmad openly referred to himself as the Mahdī. The Mahdi is an eschatological figure in Islam, who along with the mujaddid and the 12th caliph, were expected by west African African Muslims during 13th century A.H (1785 –1883) leading to the emergence of various millenarian movements which swept across the region,36 including in Sudan where West African scholars had settled in Sudan’s kingdoms of Funj and Darfur since the 18th century and become influencial37. By 1885, the revolt was successful in defeating virtually all the Ottoman-Egyptian forces that had occupied Sudan since 1821 and Mahdi’s army took Khartoum in January 1885. The charisma of Muḥammad Aḥmad, the movement’s founder, and the authority and the legitimacy of his Mahdiyya state, were inextricably linked with Muslim eschatology, and various Sudanese chiefs joined the ranks of the Mahdiyya and his prestige increased throughout Muslim ruled areas. Delegations from the Hijaz, India, Tunisia, and Morroco visited him and heard his teachings.38 Despite is correspondence with several Muslim states in West Africa, North-Africa and Arabia and its merchant’s extensive trade through its red-sea ports , the movement didn’t establish any significant foreign relations to increase its military capacity.39 In June 1885, the Mahdi passed away and was succeeded by Khalifa Abdallahi. In july 1885, Abdallāhi established Omdurman as his new capital and built the Mahdi’s tomb.40 He then took up the task of spreading the message of the Mahdiyya after consolidating his power in the Sudan, beginning in 1887, he sent letters to various foreign leaders requesting that they join his movement, not just to his Muslim peers such as the Ottoman sultan Abd al-Ḥamīd, the Khedive Tawfīq of Egypt, and the rulers of Morocco and the, but also to Christian rulers especially queen Victoria (who was now the effective ruler of the Mahdiyya's northern neighbor egypt) and to Yohannes IV of Ethiopia.41

General view of Omdurman in the early 20th century, the tunics of the Mahdiyya, silver coinage of Khalifa Abdullahi issued in 1894, Omdurman (British museum)

Conflicts over borderlands and ideology; Ethiopia and the Mahdiyya at war

The Mahdiyya inherited a borderlands dispute with Ethiopia from the Ottoman-Egyptians which ultimately shaped the Khalifa’s policy towards Ethiopia.42 In his various letters to Ethiopian rulers Yohannes IV (and his successor Menelik II), the Khalifa reactivated the ambivalent heritage of Muslim–Aksumite contacts in order to legitimize evolving policies toward their Christian neighbor, he abandoned the old tolerant tradition of Muslim states toward Ethiopia (which was itself based on a hadith written later to justify the incapacity of early Muslim empires to conquer Ethiopia, as various Muslim states did invade Aksum in the 7th century and medieval Ethiopia from the 14th century to Ahmad Gran's invasion of the 16th century). While the Khalifa had refrained from involving his forces fully in the border skirmishes with Ethiopia in 1886 that involved a series of raids and counter-raids by vassals of the Mahdi and vassals of Yohannes, by 1887 however he had changed his stance towards Ethiopia.43 In their June 1884 treaty with Ethiopia’s Yohannes, Ottoman-Egypt had agreed to retrocede the Keren region to Yohannes in return for his assistance in extricating the Egyptian garrisons in the eastern Sudan, these operations led to incidental clashes between Ethiopian troops and the Mahdists; but Yohannes recognized the Mahdist governor of Gallabat and established diplomatic relations with the Mahdi and an uneasy relationship was maintained with his successor the Khalifa whose policy towards Yohannes was purposefully ambivalent. Initially, the Khalifa refrained from the border disputes and when his ambitious governors confiscated Ethiopian merchants’ goods and launched their own incursions into Ethiopia, they were replaced and even after an Ethiopian governor of Gojjam province near the borderlands launched his own attack in January 1887 (likely without Yohannes’ approval), the Khalifa’s letter to Yohannes only asked the latter to “respect the frontiers”44 But by December 1887, the Khalifa’s stance towards Ethiopia changed, likely after weighing Yohannes' strength in the region (whose forces were pre-occupied with Menelik's insubordination and the looming Italian threat), the Mahdiyya, led by the general Abu Anja then launched two incursions into ethiopia In 1889. The first one in January defeated the forces of the province of Gojjam and advanced to old city of Gondar whose churches were sacked and looted, and a second one in June reached deep into the Ethiopian heartland, sacking the lake Tana region but retreated shortly after Menelik’s forces appeared in the region on Yohannes’ orders.45

Yohannes responded to Anja's incursion with a letter addressed directly to the later, assuring him that "I have no wish to cross my frontiers into your country nor should you desire to cross your frontier into my country. Let us both remain, each in his country within his own limits" and included an eloquent plea for peace and co-operation against "those who come from Europe and against the Turks and others who wish to govern your country and our country and who are a continual trouble to us both".46 Abu 'Anja replied, (likely without consulting the Khalifa), in provocative and very insulting terms, calling him “ignorant”, and “lacking intellect”, Yohannes’ peace proposal was interpreted as a sign of weakness (a conception Anja likely based on the internal conflict between Menelik and Yohannes and the looming Italian threat)47. This reply prompted Yohannes, who had mustered a massive army to attack Menelik, to change course and face the Mahdiyya, his forces quickly stormed Gallabat on March 1889 and crushed the Mahdist army, but this resounding victory was transformed into defeat when Yohannes sustained fatal bullet wounds, the disorderly Ethiopian retreat turned into a rout as Mahdist army quickly overran the demoralized forces and captured the emperor's remains, which were sent to Omdurman.48

The victory at Gallabat emboldened the Khalifa to launch a full scale conquest of Egypt (then under British occupation), but the campaign had been beset by ill-timing, bad logistics for provisioning it, and many had deserted, such that by the time it reached Tushki in southern Egypt in august 1889, the Mahdist force of about 5,000 led by the general al-Nujumi was crushed by the Anglo-Egyptian armies49 A follow-up attack on costal town of Suakin was met with considerable resistance and by 1891, an Anglo-Egyptian force controlled more ports south of suakin.50 These setbacks forced the Khalifa to abandon his expansionism and focus on consolidation, and while he had a number of successes in improving the Mahydiyya’s fiscal position51, the international position remained tenuous as the defeats from the Italians in 1893 and loss of the red seaport of Kassala to the same in 1894, and the new threat of the Belgians from their colony of Congo to the south-west, effectively isolated the Mahdist state, enabling the gradual advance of the Anglo-Egyptian colonial forces from the north beginning in 1896. The Khalifa then begun responding more positively to the proposals of Menelik II of Ethiopia for a formal peace on the frontier and co-operation against the Europeans, Ethiopian diplomatic missions were honorably received in Omdurman, the earlier anti-Ethiopian propaganda documents were destroyed.52

copy letter from the Khalīfah AbdAllāhi to Queen Victoria 1886 May 24 - 1887 May 27 on the former’s imminent attack on Egypt (Durham university archives)

The Ethiopia-Mahdiyya alliance of convenience: Menelik and the Kahlifa

In Ethiopia, the death of Yohannes led to a brief contest of power that was quickly won by Menelik II, who through shrewd diplomacy and military conquest had been expanding his power from his base in the province of Shewa, at the expense of his overlord Yohannes, and had built up a formidable military enabled by his control of the trade route to the Indian-ocean ports on the Somali coast.53 While his activities consolidating his control in Ethiopia are beyond the scope of this article, Menelik's pragmatic approach to the Mahdists provides a blueprint for how he maintained his autonomy during the African colonial upheaval preceding and succeeding his monumental victory at Adwa.54 Menelik had maintained fairly cordial relations with the Khalifa despite the circumstances of Yohannes’ death and continued Mahdist skirmishes, and when Menelik heard the news of the Italian occupation of Kassala in 1894 (which had dislodged the Mahdists) he held a council to discuss what steps should be taken. It is reported that some of his counselors pointed out that they should refrain from taking sides, since both (Italians and Mahdists) were proven enemies. Menelik retorted by saying that: “the Dervishes only raid and return to their country, whereas the Italians remain, steal the land and occupy the country. It is therefore preferable to side with the Mahdists.” he sent several delegations to Omdurman including one in 1895 with a letter "When you were in war against Emperor Yohannes, I was also fighting against him; there has never been a war between us…Now, we are confronted by an enemy worse than ever. The enemy has come to enslave both of us. We are of the same color. Therefore, we must-co-operate to get rid of our common enemy", The Ethiopian and the Mahdiyya empires thus entered an alliance of convenience.55 A similar alliance of convenience against colonial expansionist forces had been created between the Wasulu emperor Samory Ture and the Asante king Prempeh in 1894/1895 faced with the French and British threats around the same time.56

In February 1896, the Mahdists advanced near Kassala and were engaged with the Italian forces that had garrisoned in the town, but were repelled by the latter, a few days later, Mahdist envoys were present in Menelik's camp at Adwa on March 1896 when he inflicted his historic defeat on the Italian army.57 Despite the Mahdist loss at Kassa versus the Ethiopian victory at Adwa, Menelik didn’t alter his policy towards the Mahdists but rather strengthened it, fearing the intentions of the British who had seized the occasion of the Italian loss to advance into Sudan in march 1896, despite his position of strength Menelik, through his governor addressed the Khalifa in July 1896 as “the protector of Islam and the Khalifa of the Mahdi, peace be upon him!” in a very radical break from Ethiopia’s past correspondence with the Mahdists (or indeed with any Muslim leader) he informs the Khalifa that he is now anxious “to establish good relations with you and to cease friendly relations with the whites”, in particular, the British, he also assures the Khalifa “your enemy is our enemy and our enemy is your enemy, and we shall stand together as firm allies”58. The letter was sent during the earliest phase of the Anglo-Mahdist war when the British had made their initial advance into the northern Mahdiyya territories of Dongola in March 1896, but couldn’t take them until September 1896.59 Menelik was alarmed by the British advance into Sudan, he had long suspected them of being in alliance with the Italians during the failed negotiations that preceded the war with Italy, and their northern advance from their colony in Uganda into Ethiopia’s south-western territory further confirmed his fears of encirclement, Menelik continued to send more gestures of alliance to the Khalifa warning the latter not to trust the British, French or Belgians, and informing him of the latter two's movements in southern Sudan, assuring him to "be strong lest if the europeans enter our midst a great disaster befall us and our children have no rest".60

1896/1897, Abstract of a despatch from Menilik II, Emperor of Ethiopia to the Khalīfah warning him that the English and al-Ifranj (Belgians or French) were approaching the White Nile from east and west. (Durham University archives)

contemporary illustration of the Ethiopian-Italian battle at Adwa

contemporary illustration of the Khalifa leading his army to attack Kassala

Hoping to stall the formation of the formalization of this Ethiopian-Mahdist alliance, the British signed a treaty with a reluctant Menelik for the latter to not supply arms to the Mahdist (similar to a threat they imposed on Samory in 1895 to not supply the Asante with arms prior to their invasion of the latter in 189661). To counteract the British, Menelik also signed a treaty with France (who were about to fight the British for Sudan in the Fashoda crisis), in which he promised to partition part of Mahdiyya’s Nile-Sobat confluence in the same year62. But in his dealings with the Khalifa, Menelik simply ignored the European treaties, including the French one that required a military occupation, when the French approached the region, he sent a governor to set up an Ethiopian flag and immediately removed it, begging the Khalifa not to misunderstand his intentions, and despite the Anglo-Mahdist wars leaving a power vacuum in most of the Ethiopia-Sudan borderlands, Menelik chose not to press his military advantage, choosing to send diplomatic missions in most parts for token submission, Menelik strove to maintain good will of the Khalifa continuing a cautious border policy of deference and restrain as late as February 1898.63 By September 1898, the invading force had reached Omdurman, the Mahdist army, poorly provisioned and with a limited stock of modern rifles, fell.64

From 1896 until the collapse of the Mahdiyya in 1898, Menelik, according to the words of Sudan's Colonial governor Reginald Wingate, had sought to "strengthen the Khalifa against the (Colonial) government troops, whom he feared as neighbors preferring the dervishes(Mahdiyya)"65 but with the total collapse of the Mahdiyya, Menelik's policy of restraint became irrelevant and he abandoned it.

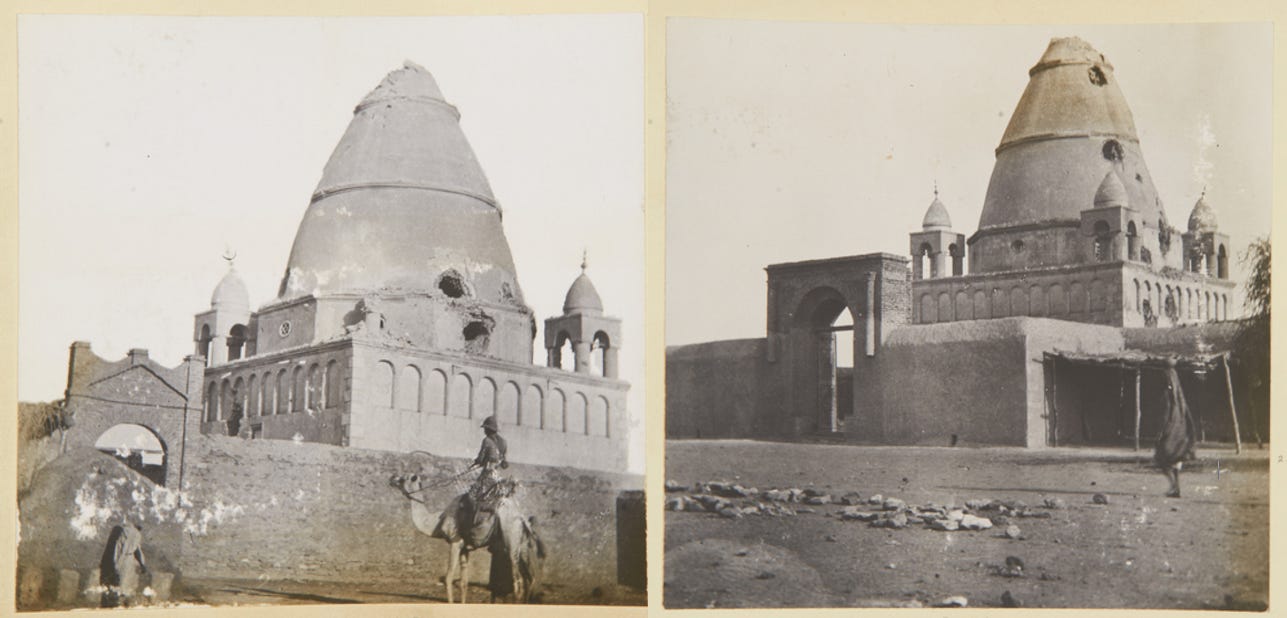

symbol of destruction; the tomb of the Mahdi damaged during the British invasion (photo taken in 1898)

Conclusion: Finding the elusive pre-colonial African solidarity.

The alliance of convenience between Ethiopia and Mahdist Sudan on the eve of colonialism provides an example of co-operation between African states in the face of foreign invasion, an African alliance that was considered concerning enough to the colonial powers that they sought to suppress it before it could be formalized. While the initiative from Menelik to the Khalifa wasn’t immediately reciprocated, this had more to do with the political realities in the Mahdiyya whose army was battling invasions on several fronts, and its these same political realities that prevented a more formal cooperation between the Asante King Prempeh and the Wasulu emperor Samory Ture. Yet despite unfavorable odds, both pairs of African states transcended their ideological differences to unite against the foreign invaders; Wasulu and the Mahdiyya were Muslim states while Ethiopia was Christian, and Asante was traditionalist.

The example of Ethiopia and Mahdist Sudan shows that African states’ foreign policy was pragmatic and flexible, and reveals the robustness of African diplomacy and solidarity at the twilight of their power.

SPECIAL THANKS TO ALL DONORS AND PATRONS FOR SUPPORTING THIS BLOG

Subscribe to my Patreon for Books on African history including Ethiopia and the Mahdiyya

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 5: c. 1790-c. 1870 pg 71-74)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 5: c. 1790-c. 1870 pg 74)

The Cross and the River by Haggai Erlich pg 65)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 5: c. 1790-c. 1870 pg 75)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 5: c. 1790-c. 1870 pg 79-80)

Imperial Legitimacy and the Creation of Neo-Solomonic Ideology in 19th-Century Ethiopia by Donald Crummey pg 23)

Layers of Time by Paul B. Henze pg 146)

Ethiopia and the Middle East by Haggai Erlich pg 57)

The Cross and the River by Haggai Erlich pg 66-69)

Layers of Time by Paul B. Henze pg 147

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 5 : c. 1790-c. 1870 pg 95

Khedive Ismail's Army By John P. Dunn pg 111-112

Layers of Time by Paul B. Henze pg 147

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 5 : c. 1790-c. 1870 pg 96

Khedive Ismail's Army By John P. Dunn pg 120

Khedive Ismail's Army By John P. Dunn pg 113, 114

Khedive Ismail's Army By John P. Dunn pg 152

The Cross and the River by Haggai Erlich pg 70)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 5 : c. 1790-c. 1870 pg 97-99

The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1870 to 1905 pg 654)

The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1870 to 1905 pg 595-601)

The Cross and the River by Haggai Erlich pg 71)

The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1870 to 1905 pg 605-608)

The Cross and the River by Haggai Erlich pg 69)

The Cross and the River by Haggai Erlich pg 72)

"Transborder" Exchanges of People, Things, and Representations: Revisiting the Conflict Between Mahdist Sudan and Christian Ethiopia, 1885–1889 by Iris Seri-Hersch pg 5

The Other Abyssinians: The Northern Oromo and the Creation of Modern Ethiopia, 1855-1913 by Brian J. Yates pg 69

The palgrave handbook of islam by fallou Ngom pg 462-63)

Kingdoms of the Sudan by R. S. O'Fahey pg 59-61)

The kingdoms of sudan pg 90-92)

The Formation of the Sudanese Mahdist State by Kim Searcy pg 18-19)

Prelude to the Mahdiyya by Anders Bjørkelo pg 35)

Prelude to the Mahdiyya by Anders Bjørkelo 108-103)

The river war by Winston Churchill pg 29-30

Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith: Aḥmad Lobbo, the Tārīkh al-fattāsh and the Making of an Islamic State in West Africa by M Nobili, pg 109-114, 227

The Formation of the Sudanese Mahdist State by Kim Searcy pg 80-88

The Formation of the Sudanese Mahdist State by Kim Searcy pg 29-34)

The Sudanese Mahdia and the outside World: 1881-9 P. M. Holt pg 276-290

The Formation of the Sudanese Mahdist State by Kim Searcy pg 107-108, 111-113

The Formation of the Sudanese Mahdist State by Kim Searcy pg 131-136)

"Transborder" Exchanges of People, Things, and Representations by Iris Seri-Hersch

Confronting a Christian Neighbor: Sudanese Representations of Ethiopia in the Early Mahdist Period by I Seri-Hersch pg 258-259)

Confronting a Christian Neighbor: Sudanese Representations of Ethiopia in the Early Mahdist Period by I Seri-Hersch pg 259)

Confronting a Christian Neighbor: Sudanese Representations of Ethiopia in the Early Mahdist Period by I Seri-Hersch pg 251)

The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism by Paulos Milkias, Getachew Metaferia pg 120)

Confronting a Christian Neighbor: Sudanese Representations of Ethiopia in the Early Mahdist Period by I Seri-Hersch pg 260)

The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1870 to 1905 pg pg 654-655)

A History of the Sudan P. Holt pg 76)

Lords of the Red Sea by Anthony D'Avray pg 90-161

Fiscal and Monetary Systems in the Mahdist Sudan by Yitzhak Nakash pg 365-385

The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1870 to 1905 pg 639, Confronting a Christian Neighbor by I Seri-Hersch 252)

The Cambridge History of Africa: From 1870 to 1905 pg 653)

Conflict and cooperation between ethiopia and the mahdist state by G. N. Sanderson

The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism by Paulos Milkias, Getachew Metaferia pg 119)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 301-304

The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism by Paulos Milkias, Getachew Metaferia pg 1201-121).

Conflict and cooperation between ethiopia and the mahdist state by G. N. Sanderson pg 30-31

The history of sudan P. holt pg 80

Conflict and cooperation between ethiopia and the mahdist state by G. N. Sanderson pg 34)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 310-324)

Conflict and cooperation between ethiopia and the mahdist state by G. N. Sanderson pg 35-36

Conflict and cooperation between ethiopia and the mahdist state by G. N. Sanderson pg-37

The history of sudan P. holt pg 82)

Conflict and cooperation between ethiopia and the mahdist state by G. N. Sanderson pg 33