An African kingdom on the edge of empires: Noubadia between Rome and the Caliphate. (400-700AD)

the transition from classical to medieval Africa.

The collapse of Kush heralded a period of upheaval in north-east Africa, with the disappearance of central administration, the abandonment of cities, and a general social decline characterized by unrest and insecurity, that was only stemmed by the rise of the kingdom of Noubadia.

Noubadia was at the nexus of cross-cultural exchanges between north-east Africa and the Byzantium, and its military strength served as a bulwark against the region's domination by the expansionist armies of the early caliphate which ultimately subdued much of the Mediterranean.

This article explores the history of Noubadia and the relationship which the kingdom had with the Byzantine empire and the Rashidun Caliphate.

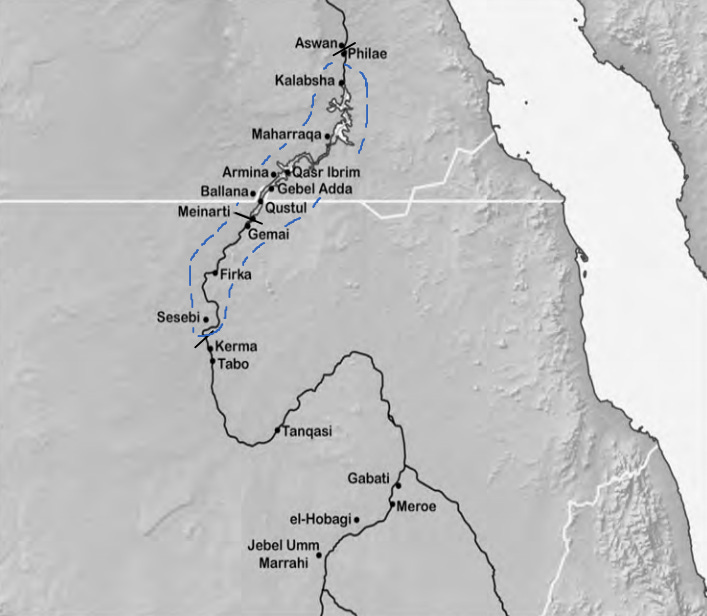

Map showing the extent of the kingdom of Noubadia between Egypt and Sudan

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Ancient Nubia following the fall of Meroe in 360AD.

After the decline of central authority at Meroe and the disappearance of a unified culture of Kush in the 4th century —as pyramid construction ceased, Meroitic writing was discontinued, and the kingdom's palaces and temples fell into ruin—, the former territories of Kush were taken over by smaller incipient states, which quickly grew into three powerful kingdoms that would later dominate most of the Nile valley during the medieval era.1

The most socio-politically dominant group within Kush’s successor states were the Noubades (an ethnonym that also appears as the Nobates/Annoubades/Noba/Nubai in other sources), representing a distinct ethnic group in the middle Nile-valley region, that was nevertheless linguistically related to the Meroitic-speakers who had dominated Kush, as both of these languages belong to the North-East Sudanic subgroup of the Nilo-Saharan language family.2

The Noubades had been living in the western frontiers of Kush since the 3rd century BC, they were subject to a number of incursions from Kush's armies at the height of Meroe (100BC-100AD) and are represented in a number of "prisoner" figures. The Noubades would later be gradually assimilated into Kush, along with a different nomadic group called the Blemmyes —the latter of whom were often at war with both Kush and Rome, and following the fall of Kush, would establish an independent state centered at the city of Kalabsha in 394. The conflict between the Noubades and the Blemmyes would greatly shape the establishment of the Noubadian kingdom, as the earliest of the three Nubian kingdoms which succeeded Kush.3

Rise of Noubadia and the fall of the Blemmyan state (394-450)

Fragmentary historical sources provide some insights into the socio-political situation in the decades after the fall of Kush, as the latter's power was extinguished following the two Aksumite invasions between 350-3604. There is evidence for continuity between Kushite and Noubadian periods in terms of the continued use and occupation of the sites and the cultural practices of the populations.5

Following the establishment of the Blemmyan state at Kalabsha in the late 4th century, a roman diplomat from Thebes named Olympiodorus visited the region in 423, and noted that Blemmyan power centered at Kalabsha extended over several towns within the 1st cataract area (the region now under lake Nasser). The Blemmyan capital Kalabsha was an important cult site centered at the temple of the Kushite deity Mandulis . On this temple’s walls were royal inscriptions of different rulers, in different scripts from the late 4th-mid 5th century including Greek inscriptions left by; the Blemmyan kings (Tamal, Isemne, Degou, and Phonen) and one by the Noubadian king Silko; as well as a meroitic inscription left by (an earlier) Noubadian king Kharamadoye.6

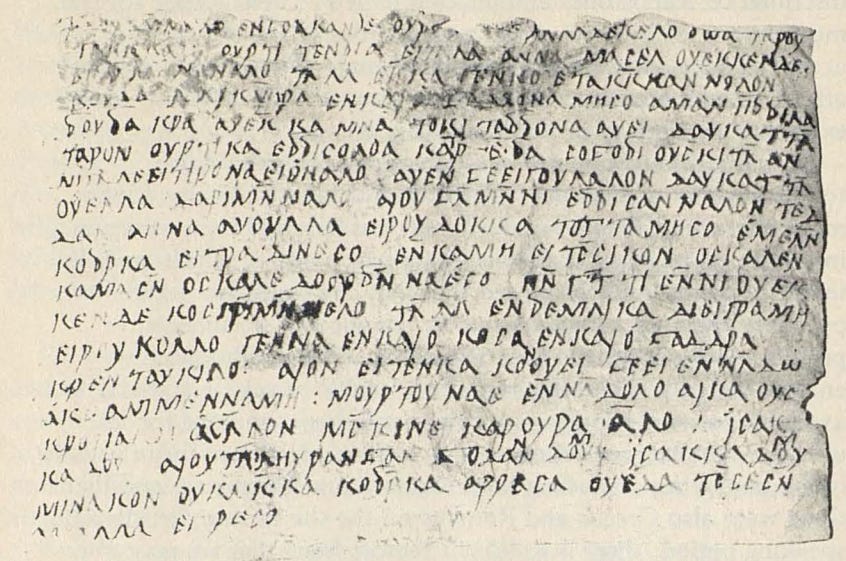

4th/5th century Meroitic inscription of the Noubadian King Kharamadoye against the Blemmyan king Isemne, found at the Mandulis temple at Kalabsha.

The Noubadian inscriptions at Kalabasha on the other hand, represent the kingdom's northward push from its capital at Qasr Ibrim where its kings were based during the 5th century. Early in its formative era, the Noubadian state had extended its control over the old meroitic cities of Faras and Gebel Adda located not far from the Noubadian royal necropolises of Qustul and Ballana within the 2nd cataract region. Between 423 and 450, Noubadia’s kings launched a number of campaigns northwards directed against the Blemmyan rulers in the 1st cataract region.7

A 5th-century victory inscription, made by the Noubadian King Silko records his three major campaigns against the Blemmyes, in which he also identifies himself as “king of the Nobades and all the Aithiopians”. In the course of his campaigns, king Silko's first victory ends with a peace treaty with the Blemmyes, that was reportedly broken by the latter prompting two more campaigns, the last of which ended with his occupation of Kalabsha and the decisive defeat of the Blemmye ruler, who then became Silko's subject. A Blemmyan perspective of these defeats is presented in a letter written by the subordinate Blemmyan ruler Phonen to Silko's successor Abourni found at the latter's capital in the city of Qasr Ibrim, in which the former pleads with the latter to restore some of his possessions, but to no avail.8

5th century Greek inscription by King Silko and his depiction on the Mandulis temple at Kalabsha.

5th century Greek letter by the Blemmyan ruler Phonen to the Noubadian king Abourni, found at Qasr Ibrim.

The Noubadian Kingdom

Following their conquest of the 1st cataract region, successive Noubadian kings, including; king Abourni, king Tantani, king Orfulo, and king Tokiltoenon in the 5th-6th century, extended their control south into the 3rd cataract region moving the kingdom's capital from Qasr Ibrim to Faras, and establishing a more complex administrative system, with subordinate regional elites. Noubadia’s cities were major centers of domestic crafts production, and the kingdom engaged in extensive trade, including external trade with Byzantine Egypt, regional trade with the emergent Nubian kingdoms to its south like Makuria and Alodia, as well as domestic trade and gift exchange internally.9

Noubadian cities and other urban settlements were characterized by monumental stone and mudbrick architecture for both domestic and public functions, they were enclosed within city walls and other fortifications, and were laid out following the classic meroitic street grid. The largest Noubadian settlements included the capital city of Faras with its palatial residences; the regional administrative centers Qasr Ibrim, Firkinarti and Gebel Sesi; the sub-regional cities like Meinarti and the fortified cities of Sabagura, Ikhmindi and Sheikh Daud; as well as a continuous string of walled towns and villages along the banks of the Nile.10

ruins of the Noubadian city of Sabagura built in the 6th century

ruins of the cathedral of Faras, originally constructed in the 7th century, but rebuilt in 707 after the original church was destroyed in a storm.11

Relations between Byzantine-Egypt and Noubadia: Christianizing Nubia.

Noubadian rulers cautiously chose certain cultural aspects derived from their interactions with Byzantine Egypt, which they then adapted into their local cultural context. The most notable being the use of the Greek script (in lieu of Meroitic) and the adoption of Christianity. While previous scholarship regarded the Noubadia kingdom as politically subordinate to Rome, recent research has rendered this untenable. The primary claim of Noubadia’s subordinate relationship to Rome is given by the ambiguous status of the early Noubadian state based on the royal titles its kings were referred with, and king Silko’s supposed position as a foederati (a term that included both independent and client states on the Roman frontier).12

The main source of confusion are the titles for Noubadian kings used by external writers. While the roman official Viventius used the title phylarchos for the Noubadian king Tantani, this was because the title basileus was reserved for the Roman emperor for roman writers13. But this wasn't the case for Noubadian scribes, as it was this exact title (both basileus and basiliskos) which the Noubadian king Silko used in his Greek inscription to describe himself, as the paramount authority in Noubadia who was independent of any other state14. The other claim that the Romans allied with the Noubadian king Silko in a federate relationship, is mostly conjectural. This is suggested by the existence of archeological finds of roman luxury items in Noubadian elite burials, which in other roman frontiers had been presented to federate rulers, but in Noubadia were most likely derived from gift-exchanges, considering that there are no mentions of such a relationship in Noubadian or Roman texts.15

Noubadia’s conversion to Christianity was a gradual and syncretic process as represented by the persistence of non-Christian practices within the kingdom. The former capital at Qasr Ibrim remained a center for “pagan” pilgrimage, alongside other sites such as Kalabsha and Philae (in Byzantine Egypt) , whose temples were open until 537. The monumental Noubadian royal burials at Qustul (in use from 380-420) and Ballana (in use from 420-500)16 are also largely pre-Christian, but their grave goods, which include artwork and weaponry of both domestic and foreign manufacture, came to include Christian items during their terminal stages, such as baptismal spoons as well as a reliquary and a censer that were included in a tomb at Ballana, dated to 450-475.17

5th century Pre-christian Noubadian silver crowns embossed with beryl, carnelian and glass, found in the royal cemetery of Ballana. The design of the crowns was partly based on Meroitic models and insignia but were unlikely to have worn during the king's lifetime18. (Nubian museum Aswan)

The name of one of Silko’s sons; Mouses, which is included in the letter written by Phonen to the Noubadian king Tantani, also points to a conversion to Christianity by the Noubadian royals, as the name was common among the Christianized populations of Byzantine Egypt during the time19. The initial adaptation of Christianity was a top-down affair that enabled the Noubadian rulers to centralize their power and integrate themselves into the then largely Christian Mediterranean world with which they traded and were engaged in cultural exchanges.20

The formal adoption of Christianity in Noubadia however, begun with a Monophysite mission from the Byzantine Empress Theodora which reached Faras in 543, and a second mission that returned in 556 to assist in the establishment of an independent Noubadian bishopric at Faras, during the reign of the Noubadian king Orfulo. By the 7th century, the Noubadians had a unique Christian culture centered at Faras, with bishoprics at Qasr ibrim, Sai, and Qurte.21

Temple ruins at Qasr Ibrim, originally built by taharqa in the 7th century BC, but later converted into a church in early 6th century AD.22

Rashidun Caliphate and Noubadia

After the Rashidun caliphate's conquest of Byzantine Egypt between 639 and 641, the caliphate's armies turned their sights on Noubadia. There are several different accounts of the Arab invasion of Nubia in 640/641, most of which post-date the invasion and identify the Noubadian kingdom as the primary foe of the Caliphate's armies, differentiating it from the more southerly kingdom of Makuria, with which Noubadia would later unite and would be conflated in other accounts.23

In 641, the Rashidun force led by the famous conquer Uqba Ibn Nafi faced off with the armies of Noubadia. A 9th century account written by the Arab chronicler Al-Baladhur records the decisive Nubian victory over the Arab forces;

"When the Muslims conquered Egypt, Amr ibn al-As sent to the villages which surround it cavalry to overcome them and sent 'Uqba ibn Nafi', who was a brother of al-As. The cavalry entered the land of Nubi like the summer campaigns against the Greeks. The Muslims found that the Nubians fought strongly, and they met showers of arrows until the majority were wounded and returned with many wounded and blinded eyes. So the Nubians were called 'pupil smiters … I saw one of them [i.e. the Nubians] saying to a Muslim, 'Where would you like me to place my arrow in you', and when the Muslim replied, 'In such a place', he would not miss. . . . One day they came out against us and formed a line; we wanted to use swords, but we were not able to, and they shot at us and put out eyes to the number of one hundred and fifty."24

The Noubadian victory was reportedly followed by a truce -that was most likely imposed by themselves, and is claimed to have been broken after the death of the caliph Umar in 644, after which the Noubadian forces advanced into upper Egypt, beginning a pattern of warfare that would characterize most of Nubian-Egyptian relations until the 10th century.25

The exact nature of Noubadia's unification with Makuria in the 7th or early 8th century is still debated, with most scholars following the common interpretation of the (post-dated) Arabic documents which place it before the battle at Dongola in 65126, while other scholars place the unification in 707 under king Merkurios.27 In either case however, the Nubians (Noubadia and/or Makuria) were ultimately victorious over the invading Arab armies and were the ones who imposed a truce on their defeated foes, in a treaty which was modified in later accounts as the balance of power oscillated.28

the churches at Qasr Ibrim and Sabagura, the earliest phase of construction at Qasr Ibrim begun in the late 7th century during the time of Noubadia’s unification with Makuria.29

Conclusion: Noubadia’s position in African history.

The rise of Noubadia was a significant event in the political history of Northeast Africa. While old theories which posited Noubadia as a "conduit" for the diffusion of Mediterranean cultural aspects have been discarded as such aspects were only selectively syncretized into its local cultural milieu, the kingdom was nevertheless at the center of cross-cultural exchanges and trade between north-east Africa and the Mediterranean, and it was thanks to its military strength that the region retained its political autonomy, defining the political trajectory of medieval Africa on its own terms.

Is Jared Diamond’s “GUNS, GERMS AND STEEL” a work of monumental ambition? or a collection of speculative conjecture and unremarkable insights.

My review Jared Diamond myths about Africa history on Patreon

if you liked this Article and would like to contribute to African History, please donate to my paypal

The Nubian past by David Edwards pg 182-183)

The Meroitic Language and Writing System by Claude Rilly pg 174)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 515-525)

Aksum and Nubia by George Hatke pg 97-101)

The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski pg 19-22)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 525-526)

The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski pg 98-99, 197)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 528-529)

The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski pg 191-192, 197-198, 151-160)

The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski pg 99-105)

Was King Merkourios (696 - 710), an African ‘New Constantine by Benjamin Hendrickx pg 11

Romans, Barbarians, and the Transformation of the Roman World by Ralph W. Mathisen, Military History of Late Rome 284-361 By Ilkka Syvanne, pg 142-143, Aksum and Nubia by G Hatke pg 157

The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski pg 188-190

Was King Merkourios (696 - 710), an African ‘New Constantine by Benjamin Hendrickx pg 12-13

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 523)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg 520

The Christianisation of Nubia by David N. Edwards pg 90-92)

Daily life of the Nubians by Robert Steven Bianchi pg 267)

Between Two Worlds by László Török pg pg 529

The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski pg 188-190 pg 175).

The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski 169-173)

The Monasteries and Monks of Nubia by Artur Obłuski pg 98)

The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski pg 199)

Ancient Nubia by P. L. Shinnie pg 123)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 761

Was King Merkourios (696 - 710), an African ‘New Constantine by Benjamin Hendrickx pg 17

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 761-762, The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski pg 200

Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World by Jay Spaulding pg 584

The Rise of Nobadia by Artur Obłuski pg 173

I'm a great admirer of your work and I look forward to a face-to-face engagement someday. Hongera!

The details in your newsletter is second to none. I wish I could do as well as you