An enigmatic west African Art tradition: The 9th century bronze-works of Igbo Ukwu.

grave-goods of a priest-king

Over a period of less than a generation in the 9th century, a group of artists in a kingdom straddling the edge of the west African rainforest produced some of the world’s most sophisticated artworks in bronze, copper and terracotta, which they then interred in a rich burial of their priest-king.

This extraordinary art corpus, which was stumbled upon during construction work in the early 20th century, seemingly bursts into the archeological record without precedents, yet doubtlessly represented a full flowering of an old artistic tradition.

This article explores the history of Igbo Ukwu art traditions within the political and cultural context of the Nri-Igbo society, inorder to demystify the enigma of Igbo Ukwu.

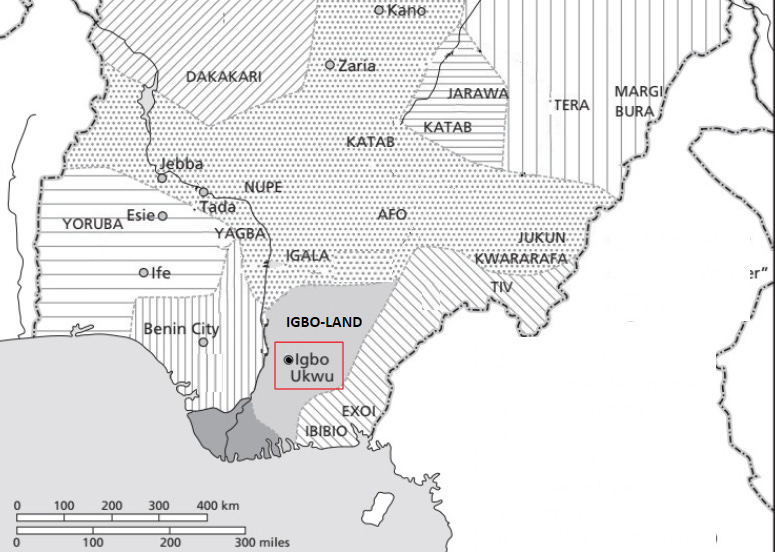

Map showing Igbo-Ukwu and the Igbo-lands

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

A political history of Igbo Ukwu; the Nri political-religious organisation

The history of political developments in Igbo-land (south-eastern Nigeria) before and during the emergence of the Igbo Ukwu tradition are rather obscure. Governance in the early small-scale polities of the forest region was associated with priests of the earth-goddess, agnatic heads of lineages, and a council of elders. The traditions of one particular Igbo subgroup; the Nri, posit them as reputed ritual specialists who developed a hegemonic state headed by hereditary sacred rulers who conferred titles on prominent individuals. The Nri's mythical founder, Eri, is said to have descended from the sky to the Anambra River prior to the domestication of the igbo staples; yams and coco-yams, and with the help of autochthonous cultivators, traders and blacksmiths, developed farming, iron technology, and controlled markets that enabled the establishment of a fairly centralized state between the 9th and 10th century.1

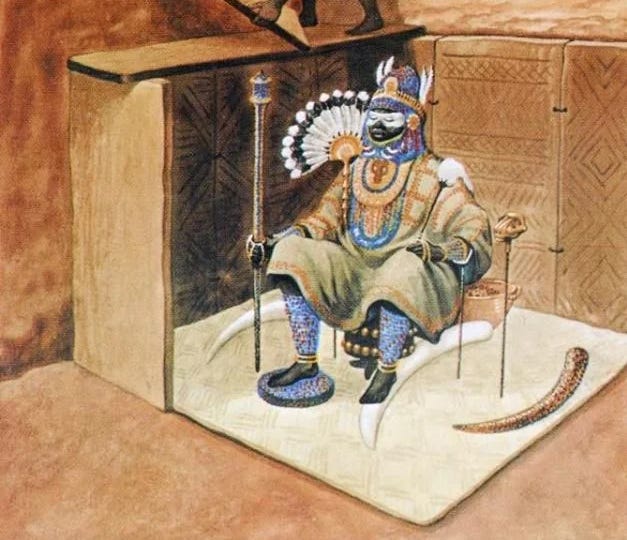

The Igbo concept of political-religious power is structured by membership in associations based on an elaborate title-system and patrilineal lineages called umunna, and is thus highly diffused. Within the cultural area of the Nri subgroup, the most powerful title-holder is the Eze office, ie Eze-Nri a dignitary with religious and political authority, who was subordinated by other title-holders (Ozo) who were involved in the Nri governance system.2 Central to the Nri social organization is the Obu temple, which is kept for ritual and ceremonial purposes in connection to the title system, and is often located within the main compound of a title-holder's household for the collection of prestige items. Upon his death, the Eze was buried, often in a seated posture, with prestigious grave goods and his coronation clothes.3

The institution of the Eze Nri, its title-taking system and many aspects of the Nri culture including the Obu temples present us with the best evidence for explaining the objects discovered. By drawing parallels with their occurrence in extant traditions, it can be surmised that they represent a concentration of wealth accruing to the institution of the Eze Nri, and the objects could be regarded as material metaphors which symbolically represented the office's power4

Virtually all the artifacts buried at Igbo-Ukwu, with the probable exception of the beads, were manufactured locally. The artistic inspiration of the the metalwork, consisting of a wide variety of elaborately fashioned and profusely decorated bronze and copper pieces, was largely local, its motifs, casting techniques, and metal ores sources bearing no comparison with anything else outside the region.5

The volume, complexity, and richness of the Igbo Ukwu art collection which included imported glass beads, suggest that the already established iron-age agricultural community of the Nri kingdom, received a further impetus of wealth accumulation and display in the late first millennium through its engagement in regional trade routes. This connection was marginal, and is unlikely to have been undertaken using a direct routes but was instead more likely to have been segmented, with imports circulating through various local markets, before being obtained by the wealthy figure(s) buried at Igbo Ukwu.6

Demand for a variety of adornment that included imported glass beads was created by their use in the title-taking ceremony for Ozo title-holders which also involves their adornment with semi-precious carnelian stones and glass beads, that are also worn by wealthy individuals in igbo-land to symbolize their social status. 7 The most likely trade item exchanged from Igbo Ukwu region was ivory. Igbo Ukwu is ideally situated for obtaining elephant ivory within the West African forest zone, which was funneled through the trading cities of the Sahel, such as Gao, which is the nearest of the major cities, and whose material culture included glass beads similar to Igbo Ukwu, albeit at at slightly later date in the 11th century.8 A number of elephant tusks were found among the grave goods as well as several representations of elephant heads, and this is likely related to the practice of Ozo title-holders presenting ivory horns upon initiation, that are later collected and kept in their respective temples.9

A brief description of the excavations at Igbo Ukwu and the casting process

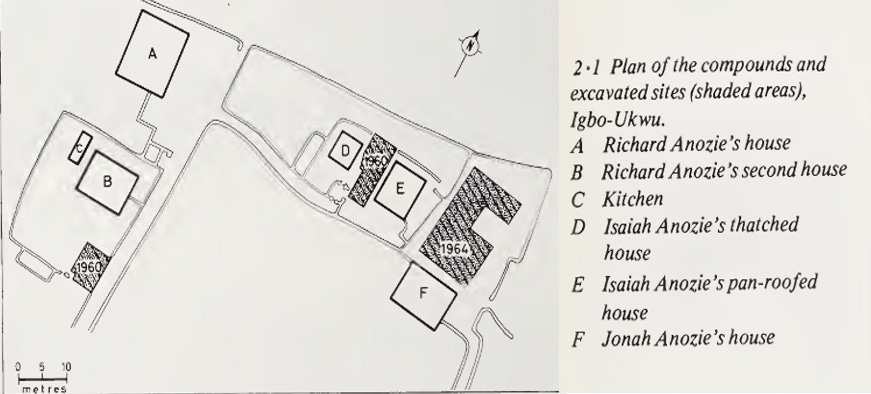

Excavations undertaken in the 1930s and 1960s uncovered a remarkable array of over 700 artworks primarily cast in bronze, copper and copper-alloys, along with works of terracotta, and over 165,000 glass and carnelian beads, that were all deliberately interred with the remains of at least six individuals in three sites that were named after the owners of the compounds on which the objects were found; Igbo-Richard, Igbo-Isaiah and Igbo-Jonah, all of which were dated to between 850-875AD. 10

Igbo-Isaiah appears to have been an Obu temple which had decayed without trace save for four post-holes that constituted some form of roofing. Igbo-Richard represented the remains of a burial chamber once lined with wooden planks and floored with matting, and given its collection of grave goods, has been interpreted as the burial of the Eze-Nri. Igbo-Jonah, was as a pit used for the deliberate disposal of a collection of ritual and ceremonial objects following the razing of a shrine house.11

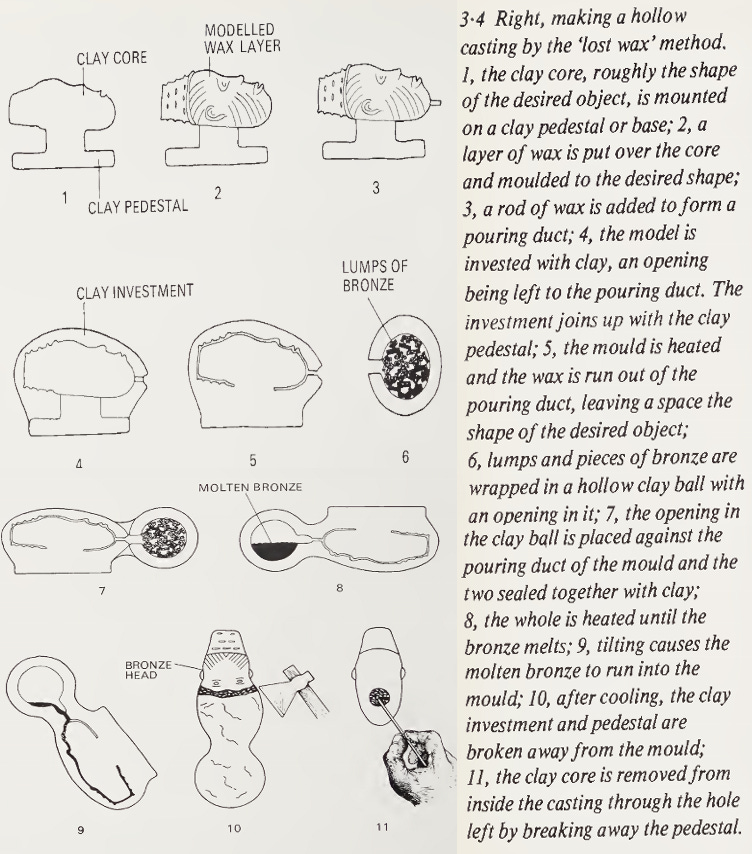

The majority of the 700 objects found at Igbo Ukwu were made using a combination of lost wax casting for the leaded-bronze objects, while those of copper were made by smithing and chasing.12 The copper and lead ore was mined locally in the Abakaliki region, about 100km from Igbo Ukwu, while the tin that was alloyed to form bronze was derived from mines close to Igbo Ukwu, or from the jos plateau.13

The cire-perdu casting involved modeling the desired object in wax (or in this case latex from the Euphorbia plant), the obtained model of which is then dipped in clay which is then heated to leave a fired clay model, into which molten bronze is poured and the clay broken off. The exact technique used for the Igbo Ukwu bronzes involved a slightly more complex process than this; with objects often cast in many pieces that were then joined together by separately poured in metal, but this process had been out of use across the rest of the old world for many centuries, which strongly suggests its independent invention by Igbo Ukwu artists working in isolation.14

map of the excavated site

Illustration of the lost-latex casting process of Igbo-Ukwu bronzes according to T. Shaw, 1977

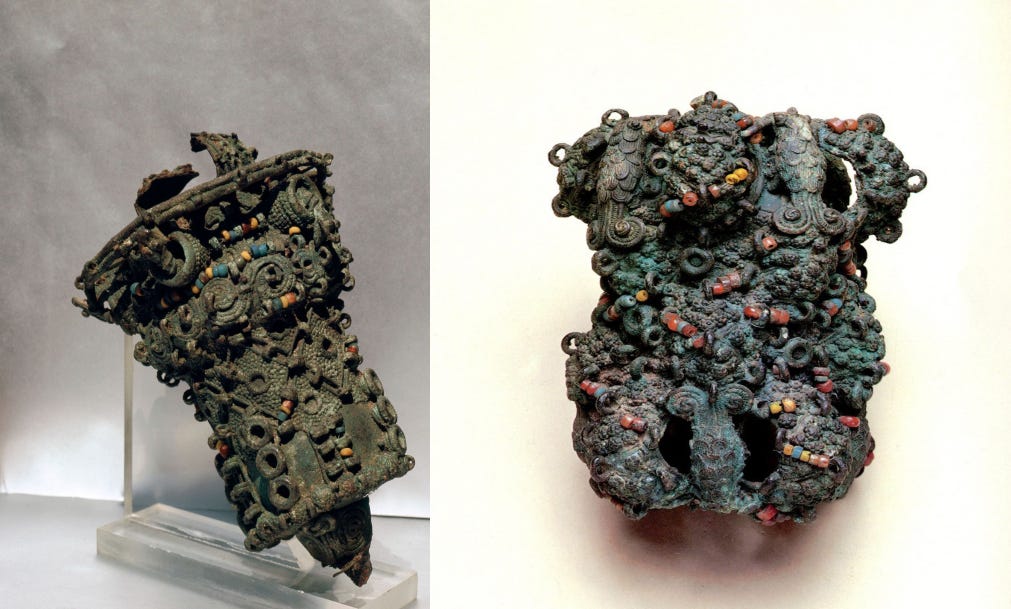

The Igbo-Ukwu bronzes

Among the most notable objects were ornaments with human figures whose faces are marked with scarifications radiating in all directions from the bridge of the nose. These are facial marks (ichi) found all over the igbolands and practiced almost exclusively on men being part of an initiation rite into the title-holding system by boys around the age of 11, but these scarifications aren't made on women save for the daughter of the Eze Nri.15Similar depictions of facial scarifications also appear on cylindrical "altar-stands" made of panels of solid bronze decorated with patterns of hatched lozenges and triangles with stylized figures of spiders. Between the panels are walls of open-work with figures of a man and woman, both with face and body scarifications and wearing body ornaments.16

The echi facial markings are often associated with the mythical origin story regarding the first Eze Nri and his introduction of cultivation in Igboland, their occurrence in twelve of fourteen representations of human heads underlies the important link between the buried figures and contemporary cultural traditions of the Nri lineages17.

bronze pendant of human head with a crown, bronze altar stand showing a female figure with facial markings, surrounded by motifs of snakes swallowing frogs and stylized spider figures, 9th century NCMM Nigeria

Igbo Ukwu artworks predominantly feature skeuomorphism; the rendering of the innate features of one material form in another. It was manifest in several ways and likely served a twofold purpose that; indicated the power of the object’s owners to transform the meaning and appearance of both every day and prestige items at will, and to produce the symbols of power and authority in more durable forms.18

Skeuomorphism was evident in several items of bronze work. The most notable of these was the bronze roped vessel that was skeuomorphic of a pear-shaped clay waterpot on its stand with a rope net around it to help support and carry it. Other skeuomorphic works are the bronze calabashes and gourds, that were modeled after common calabashes, with intricate decorations and quatrefoil patterns on the surfaces to mimic the patterns of nets surrounding common calabashes, they also include wire handles and fittings that imitate copper handles and fittings of real calabashes.19

Bronze pot on a pedestal enclosed in a rope-work cage; Cylindrical Bronze bowl on an open-work pedestal decorated with alternating figures of grasshoppers, 9th century, NCMM Nigeria

Leaded-bronze bowls, 9th century, NCMM Nigeria, British museum Af1956,15.3

Leaded-bronze bowls, 9th century, NCMM Nigeria. the crescent-shaped bowl is in the form of a calabash

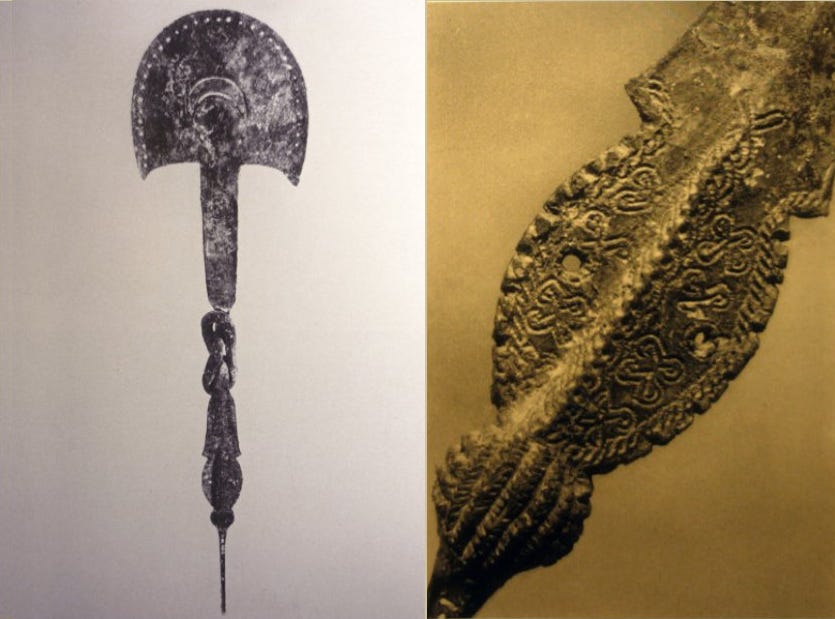

Among the Igbo Ukwu corpus were objects that symbolized political and religious authority. These objects include staff ornaments, that are some of the most richly decorated and off all the Igbo Ukwu castings; with granulated surfaces encrusted with glass beads, their sides have spirally twisted bosses, coils of quatrefoils, and geometric patterns of lozenges. Depicted on the staffs are figures of beetles or columns of mudfish and monkey-head figures, all of which are surmounted by a figure of a snake with an egg in its mouth, or figures of birds with grasshoppers/locusts in their mouth.20 Other objects of power were three types of bronze bells, and large fan-holders made of pure copper with a semi-circular plate decorated with puncate lines and interlace patterns resembling quatrefoils, the copper fan-holders were also punched with holes for fixing feathers.21

Bronze staff ornaments, 9th century, NCMM Nigeria

Copper spiral snake ornament, 9th century, NCMM Nigeria, "the spike was probably driven into the end of a wooden staff

Large bronze cylindrical staff ornament in the form of a coiled snake with a head at each end, Decorated bronze staff head with four snakes swallowing frogs, alternated by four beetles, 9th century, NCMM Nigeria

copper fan-holder whose base was originally attached to a staff, 9th century, NCMM Nigeria

The staff heads and their ornaments, as well as the fan-handles are indicative of the political-religious power held by highly ranked title-holders in igbo-land, where staffs called alo are still carried, they serve as a badge of office and offered a form of "diplomatic immunity" for the title holders. The depictions of grasshoppers and beetles is suggestive of the belief that the Eze Nri’s ability to direct the forces of nature for the benefit of the society, he could thus control the activities of creatures such as grasshoppers, locusts, flies, birds, yam-beetles, all to the advantage of his people22.

Copper rod that supported a wood and leather scabbard in which an iron blade rested

Animals in Igbo-Ukwu art

The appearance of naturalistic and stylized depictions of animals in the Igbo Ukwu artworks is tied with their use in the iconography of power in which the symbolic representations of leadership took on attributes of elephants, horses, rams, leopards, snails, tortoises, flies, as recounted in the folktales that occur in igboland.23 Serpentine figures in particular are ubiquitous in Igbo Ukwu art with snake ornaments made of pure copper, were often used to decorate ceremonial staffs. The snake depicted maybe the python (eke), it is believed to be the messenger of the earth deity (ala), and of which they are taboos across igbobland against killing them. The depiction of coiled serpentine figures that is also featured prominently in more recent igbo art, attests to the pervasiveness of the motif in igbo traditions such as the widespread proverb okilikili bu ije agwo (circular, circular is the snake's path).24

Another object indicating iconography of power was a remarkably preserved bronze hilt in the form of a horseman set on decorated pommel decorated in a grass-weave pattern surmounted by round bosses. The rider is depicted with exaggerated proportions relative to the horse, and with emphasis on the head in a style that would become ubiquitous for the region's art traditions especially in Ife and Benin. This is also one of the oldest equestrian figures in west Africa's forest region, where horses were mostly used for ceremonial display.25

Equestrian figure on a bronze hilt, 9th century, NCMM Nigeria

Other depictions of animals in Igbo Ukwu art include; bronze pendants in the form of stylized elephant heads covered with a hatching of lines and lozenge patterns with a granulated surface encrusted with glass beads, all of which is surmounted by figures of grasshoppers;26 Ornately decorated pendants in form of ram's heads whose horns curve to the back of the head, with a patterned surface and the head surmounted by a wristlet and grasshoppers27; Ornaments in the form of a leopard's skull with a face looking upwards, attached to a long copper rod28, And several bronze shells representing the triton snail-shell (found along the Atlantic coast) with granulated surfaces that are decorated with concentric circles, fly figures, snake swallowing frogs, that are inturn surmounted by a leopard, and coiled wires terminating into an ornamental sprinkler with spouts.29

Leopards, elephants, rams and snakes are often used in a general way in west African art to symbolize power, In more recent depictions from the Igbo city of Onishta, the representation of the ram's head with curving horns is seen as a reference to the king as a warrior-figure whose strength is represented in the form of carved figures featuring upthrusting horned projections.30

Bronze pendant in the form of a leopard’s head, bronze pendants in form of rams heads, bronze ram’s head, 9th century NCMM Nigeria.

Bronze pendants in form of stylized elephant heads, 9th century NCMM Nigeria.

Bronze shell with four snakes swallowing frogs and a fly-covered patterned surface, Bronze shell surmounted by a leopard, 9th century, NCMM Nigeria

Bronze ornament of two eggs surmounted by a bird, attached to it are black copper chains decorated with yellow beads and crotals, 9th century NCMM Nigeria

Conclusion: interpreting the enigma of Igbo Ukwu

The broader implications of the origin of Igbo Ukwu’s metal ores, their artists’ mastery of bronze casting in both naturalist and stylistic forms, and the interpretation of this voluminous art corpus within the cultural context of the Nri traditions; are profound. Igbo Ukwu represents an advanced bronze industry which had emerged in medieval west Africa using its own metals largely isolated from the regional and international artistic centers and technologies of the time.

The enigmatic emergence of the Igbo Ukwu art tradition in the 9th century was thus likely to have been tied to the formalization of social and political control by titled individuals associated with the Eze-Nri office during a time when wealth was used to produce durable expressions of power.31

Painting by Caroline Sassoon showing how the burial chamber with some of the grave goods of Igbo Ukwu could have been originally looked (taken from T. Shaw, 1977 pg 59)

Just like Igbo-Ukwu, the ancient kingdom of Kerma (2500 BC -1492 BC) pioneered a social and political tradition that was influential in the history of north-east Africa (especially to ancient Egypt), read about the history of Kerma on Patreon

If you liked this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal/Ko-fi

Political Organization in Nigeria since the Late Stone Age Pg 31, 42, 80, Nri Kingdom and Hegemony A.D. 994 to Present by A Onwuejeogwu pg 9-10

Political Organization in Nigeria since the Late Stone Age pg 9

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 98-99)

Material Metaphor, Social Interaction, and Historical Reconstructions by Ray K pg 68, 74. Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 102)

Metal Sources and the Bronzes from Igbo-Ukwu, Nigeria by PT Craddock pg 427

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 106-107, Gao and Igbo-Ukwu by T Insoll pg 18

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 101)

Gao and Igbo-Ukwu by T Insoll pg 18)

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 101)

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 91

Igbo-Ukwu: An account of archaeological discoveries in eastern Nigeria by Thurstan Shaw pg 263, 264, 226

Nigerian sources of copper, lead and tin for the igbo-ukwu bronzes by VE Chikwendu, pg 29)

Metal Sources and the Bronzes from Igbo-Ukwu, Nigeria by PT Craddock pg 426, nigerian sources of copper, lead and tin for the igbo-ukwu bronzes by VE Chikwendu pg 31)

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 15-19, Nigerian sources of copper, lead and tin for the igbo-ukwu bronzes by VE Chikwendu pg 29-30)

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 33, 100)

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 35)

The Archaeology of Contextual Meanings by Ian Hodder pg 76

Material Explorations in African Archaeology by Timothy Insoll pg 239, 242)

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 21-22, 68

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 28-29)

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 57)

Nri Kingdom and Hegemony A.D. 994 to Present by A Onwuejeogwu pg 52-53

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 102)

The Archaeology of Contextual Meanings by Ian Hodder pg 72

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 56)

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 32

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 33)

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 48

Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw pg 29)

The Archaeology of Contextual Meanings by Ian Hodder pg 71

The Archaeology of Contextual Meanings by Ian Hodder pg 77

Interesting I've always found the igbo ukwu culture to be so mysterious and fascinating there's so much about West Africa or Africa in general that we have to learn and discover, I read recently how they found evidence that there may be even earlier evidence of agriculture in the Sahara then previously believed I'd share the link if I can find it again.

What an extraordinary research paper!

Stunning images too.