An episode of Naval warfare on the East African coast: the Sakalava invasions of 1792-1817

Between Madagascar and the Swahili world.

Beginning in 1792 and continuing on a regular basis for the next three decades, well-armed flotillas were launched from Madagascar to attack the East African coast. They sacked cities, carried off loot and captives, and forced many to flee to the countryside. Alerted to the new threat, the navies of the Swahili, Comorian and European settlements were assembled to meet the invaders at sea.

This episode of Naval warfare on the East African coast, commonly known as 'the Sakalava invasions', is one of the least studied chapters in the military history of pre-colonial Africa and the western Indian ocean. The motives behind the sudden surge in naval invasions and the wide geographic scope of the operations, remain a subject of debate among historians.

This article outlines the history of the Sakalava invasions within the political context of the East African coastal states, to explain the motives behind the region's brief episode of Naval warfare in the early 19th century

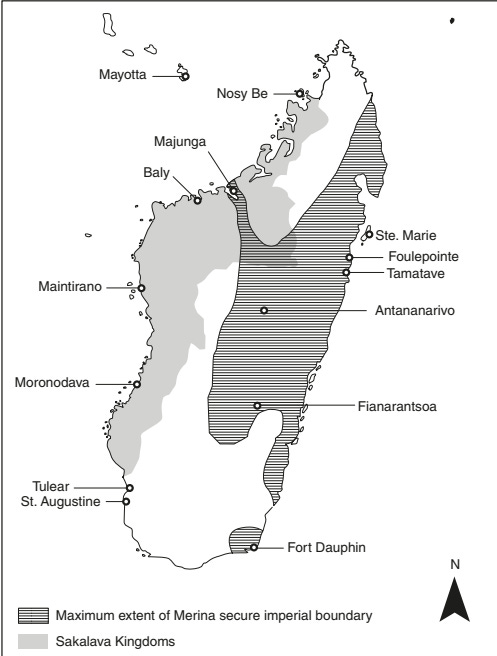

Map of the East African coast showing the range of the Sakalava invasions

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

A brief political history of Nzwani and the Sakalava kingdom of Boina in Madagascar

The island of Nzwani was home to the most prosperous kingdom in the Comoros archipelago during the 18th century, having grown as a major port-of-call for European ships which were provisioned and taxed at its main port of Mutsamudu. But Nzwani's internal politics were attimes marked by disputes in which rivaling elite factions leveraged their regional and foreign alliances to strengthen/seize authority. These often involved alliances with nearby elites from Comoros and the Swahili cities, but at times involved visiting English, Portuguese and French ships and their colonial enclaves in Bombay, Mozambique island and Mauritius.1

During the 1780s, the conflict between king Said Ahmed (based in the capital Domoni) and his cousin Abdallah (governor of Mutsamudu) reached a breaking point after the latter had refused to punish the assassins of one of Ahmed's sons. The king thus sent a force to attack Abdallah, but was defeated by the latter’s forces defeated who then proceeded to the king's palace where they deposed and killed him in 1792. Abdallah seized the throne, prompting the deceased King's son, Bwana Combo to seek the aid of Sakalava mercenaries from Madagascar. The Sakalava navies landed on Nzwani but were unable to take the walled town so they sacked and looted the surrounding countryside before leaving.2

Map showing the location of Nzwani along the important shipping routes of the western Indian ocean

View of Mutsamudu

Prior to the emergence of the Sakalava, the north-western region of Madagascar in the 17th century was a honeycomb of small chiefdoms populated by both Africans and Austronesians while the coast was dotted with city-states established by the Swahili (Antalaotse). The island had been settled permanently in the 1st millennium by speakers of both; African languages (Swahili and its Bantu peers); and Austronesian languages (mostly Malay and Javanese) and Madagascar’s population was thoroughly admixed, but the elites and much of the population often spoke one of the main languages. As one external account in 1612 describes it; "The entire coast between Mazalagem and Sadia speaks a language analogous to those of the Cafres, that is to say the language of the countries of Mozambique and of Malindi, But, in the immediate hinterland of this coast, as well as in the interior and other coastal sections, only the Buque language is spoken, one quite special to local inhabitants and totally different from the African tongues and very similar to Malay". Therefore most of the political elites who spoke African languages were in the Antalaotse coastal city-states, and there are a few mentions of African states in the interior, but the rest of the political elites on the Island spoke Malagasy dialects (eg Sakalava, Merina and Betsimisaraka). By the mid-16th century most of the small states and the coastal cities of north-western Madagascar were under the suzerainty of the Guinguimaro kingdom.3

In south western Madagascar, the first Sakalava kingdom was established in the late 17th century by king Lahifotsy (c. 1614-83). A succession dispute after his death forced his son Tsimenata (c. 1660-c. 1710) to forge his own alliances and travel northwards where he established the kingdom of Boina, which conquered the much of the former Guinguimaro territories including the Antalaotse city of Mazalagem Nova in 1685. The rulers of Boina established their capital at Majunga in 1745 which became an important coastal city, and by 1790, travelers described Boina as a powerful kingdom ruled by Queen Ravahiny (1770-1808), she was surrounded by important chiefs, dispensed strict justice, and received from foreign countries silk fabrics and luxury goods. 4

The Boina elite also formed a loose alliance with their eastern neighbor, the Betsimisaraka kingdom that was early regarded as the nominal vassal of Boina.5 The Boina kingdom's largely subsistence domestic economy was based on rice cultivation and cattle rearing, the expansionist wars that characterized its creation —and the formation of many similar kingdoms across Madagascar— also produced captives, many of whom were retained locally but some were exported externally and met the demand from French plantations on Mauritius and reunion and across the western Indian ocean. Equally important in Boina's external commerce was the provisioning trade which supplied food (cattle, rice, poultry) as well as hides and water to visiting European ships. 6

The rulers of Boina thus maintained fairly cordial commercial relations with the authorities in the east African coast and islands where their products were purchased including the Portuguese at Mozambique. They were also regularly engaged diplomatic correspondence with the Portuguese of Mozambique island. Most of Boina’s external trade was handled by Antalaotse merchants (and later by Indian traders) as it had in the past, though now with different commodities.7

Map showing the Malagasy dialects of Madagascar. Maps showing the Sakalava kingdoms of western Madagascar including the kingdom of Boina/Boeny

Mahajanga , landing port, ca. 1895

The foreign military alliances of Nzwani: an example of the Antalaotse and the French

Given their origin on the east African coast, the Antalaotse of Madagascar, whose primary trade was with the Swahili and Comoros initially involved the transshipment of Gold, and the export of soapstone, rice and livestock8, maintained political and cultural ties to the elites in the Swahili and Comoros9, as well as with the Malagasy kingdoms of Madagascar, They therefore constituted a dependable pool of allies for Nzwani's rivaling factions to draw from in recruiting Sakalava and Betsimisaraka mercenanies. And given the gradual expansion of both the provisioning and slave trades, allied armies/mercenaries were usually promised compensation in the form of greater political control, or payment in loot and captives.

One such notable request for military assistance from a Nzwani ruler to a foreign ally was sent by Ahmed, the king of Nzwani to the French in 1791, to help him re-impose his authority over Island of Mwali which challenged Nzwani's suzerainty by not paying tribute. But this combined French-Nzwani naval invasion was defeated by Mwali’s forces and many were killed, although the Nzwani king still compensated the French. Shortly after this battle, king Ahmed was defeated in 1792 by Abdallah of Mutsamudu, forcing king Ahmed's son Bwana Combo, to request assistance from the Betsimisaraka and Sakalava of Madagascar.10

Map showing the east African coastal settlements including the Antalaotse cities of north western Madagascar

ruins of the Antalotse city of Mazalagem Nova in northwestern Madagascar

The initial Sakalava invasions in the Comoros Archipelago

While Bwana Combo and his Malagasy allies lost the first battle, more invasions would were launched against Abdallah’s capital of Mutsamudu in 1796, 1798, 1803 and 1808 during which time king Abdallah and his successor king Alawi (1796-1816) repeatedly requested British assistance to fight of the attackers. The British offered little help except a brief bombardment of Domoni in 1798 to send off Bwana combo's Sakalava allies, and a consignment of weapons that was sent in 1808.11

Over the final decade of the 18th century, the Sakalava invasions were launched beyond Nzwani, especially against the polities on Mayotte in 1797, Grande Comore in 1798, with the invaders often taking loot and captives before sacking the towns. This prompted the construction of defensive walls and fortresses in the Comoros cities, and the expansion of preexisting defenses, particularly in Mutsamudu, Moroni, Mitsamiouli, Ntsaouéni and Iconi where populations took refuge by the time the invasions resumed in 1802.12

Contemporary accounts suggest that flotillas were rather decentralized and frequently provide conflicting descriptions of the attackers’ identities. While these attacks initially predominantly involved Betsimisaraka forces, they were later known almost exclusively as Sakalava since all the naval forces departed from the northwestern capital of the Boina kingdom. The watercraft used were large outrigger canoes about 10 meters long that could carry over 30 men and together constituted fleets of as many as 500 vessels carrying anywhere between 8-10,000 Sakalava soldiers with a significant proportion often armed with rifles.13

Section of an old city-wall in Ntsaoueni on Grande Comore, built to defend the city against the Sakalava

The fortress of Mutsamudu constructed in the late 18th century, the cannon were procured from the English at the height of the Sakalava invasions

The Sakalava invade the east African coast

While the motive of the Sakalava attacks beyond the internal conflicts of Nzwani is a subject of debate due to the limited documentation of the era, Its clear that there was a significant political factor driving the invasions. The internal politics of both Nzwani and the neighboring island of Mayotte was rife with de-thronings, assassinations and the extensive use of foreign alliances, with defeated rivals often being forced to flee to the Swahili cities along the East African coast, where they gathered more alliances to strike back. In 1800, the king of Mayotte arrived in the Portuguese-controlled Quirimbas Islands with a party of 150 armed Sakalava men in three boats, and stated that he intended to defeat a rival whose forces had fled to the Swahili town of Tungui near the islands. Its then that the first Sakalava attack on the east African coast is recorded, it consisted a small force that attacked the town of Tungui.14

While the Sakalava navies were organized along the north-western coast of Boina kingdom, they were not controlled by its reigning Queen Ravahiny who infact warned the Portuguese governor of Mozambique in 1805 of an impeding Sakalava attack against the latter’s dependencies. In the same year, the Portuguese encountered a Sakalava fleet on Nzwani's coast and their ship was seized by the Sakalava. Shortly after this, the king of Nzwani at Mutsamudu sent an appeal for military assistance from the Portuguese against the Sakalava since the British offered little help. The Portuguese sent an expeditionary force in 1806 into Nzwani’s waters to punish the Sakalava, but they were defeated, killed and their ship’s components were sold off.15

The three types of watercraft in the south-western corner of the Indian ocean; The Sakalava outrigger canoe, The Swahili Dau, and the Omani Sambuk, al photos from the early 19th century.

Its after the failed Portuguese punitive expedition that Sakalava navies launched a major invasion onto the East African coast in 1808, with 500 boats carrying 8,000 soldiers, and devastated the Portuguese dependencies on Mozambique coast and their neighboring communities but with a particular focus on the Swahili town of Tungui. Despite the ferocity of the attack, the invading forces suffered many causalities following a smallpox outbreak that forced them to retreat and destroy many of their boats that didn't have enough men to sail them back. Despite the loss, they carried off some captives and loot, but a number of the captives were ransomed back by the Swahili once the latter appealed to the Boina authorities at Majunga.16

The Portuguese sent a letter in 1811 to the Sakalava queen Ravahiny requesting that she put a stop to the raids in the region and she responded that the Nzwani king had provoked the raids by demanding assistance in his attacks on Mwali. She added that while her subjects had been given permission to attack the Comoros, they were not acting under her command and hence she was powerless to stop them. Further attacks by Sakalava navies were launched in 1815 against the town of Tungui but were met with defeat by its Swahili governor Bwana Hassan, and a similar planned invasion against the Portuguese controlled town of Ibo was defeated in the same year when the Portuguese fleet sailed out and met them the Sakalava flotilla sea.17

In October 1816, a massive Sakalava fleet led by a prince “Sicandar” from Nzwani sailed for the Mozambique coast ostensibly to apprehend the Swahili ruler of the Portuguese dependency of Sancul, who had detained Sicandar's wife and daughter18, but it was defeated by the Portuguese after two days of battle. Another massive Sakalava force of 500 boats led by Nassiri (who was either Comorian or Antalotse) sailed up to Kilwa in the same year, but was also defeated by the forces of Kilwa's king Yusuf bin Hassan after three days of battle. Despite their losses, the Sakalava left with over 300 captives from Quirimbas and Kilwa including some Portuguese settlers, but a number of these captives were ransomed back by the Portuguese and Swahili following appeals to the Boina authorities.19

The last Sakalava invasion occurred in 1816-7 with 18 boats being spotted heading for the coast of Kilwa and the Mafia islands where they were presumably more successful than their first battle with captives being carried off. In 1818, the sultan of Zanzibar sent an armada of 18 dhows that engaged the Sakalava navies in multiple battles at sea where many were defeated, their boats destroyed and their leader was forced to sue for peace and returned the captives taken earlier.20 Despite preparations for more Sakalava invasions, their dreaded navies were never to be seen again on the East African coast, largely due to the wars between the various Sakalava kingdoms and the rapidly expanding Merina empire which culminated with the conquest of the Boina capital of Majunga in 1824.21

Ruins of the Swahili town of Kua in the Mafia archipelago, Tanzania. Kua is said to have been abandoned after the Sakalava attacks

Conclusion: explaining the episode of Naval warfare on the East African coast.

The argument advanced by some scholars that the Sakalava attacks were driven by the demand for slaves in Madagascar and French islands due to the expansion of the Merina empire and the slave trade ban signed in 1820 by Merina king Radama I22, contradicts the evidence. Madagascar remained throughout the first half of the 19th century, a net exporter of Malagasy slaves into the western Indian ocean as it had in the centuries prior, this was because despite the expansion of the Merina empire, it barely controlled 1/3 of the Island --mostly on the eastern half-- and the regional wars between the various kingdoms especially in the west continued to sustain the supply needed to export captives, with of upto 5,000 being sold annually in the 1850s.23

Map of Madagascar showing the extent of Imperial Merina after 1824

More importantly, the well regulated trade maintained through peaceful relations between Boina and the Portuguese, that was carried out on Arab ships that had a much larger capacity than Sakalava canoes, that was conducted by Indian and Antalaotse merchants, and was supplied by many Malagasy caravans from the interior including the Sakalava,24 was disrupted rather than increased by the wars, as shown by the frequent ransoming of the captives, and the correspondence between the Portuguese and Boina rulers urging the latter to restrain the mercenaries' activities. Therefore, the massive investment in assembling 10,000 well-armed soldiers over several months to capture a few hundred slaves in well-defended cities that routinely defeated and killed many of the invaders, appears counterintuitive to the commercial dynamics of slave trade.

A more likely explanation advanced by Edward Alpers, views the Sakalava naval wars as an outgrowth of the political conflicts that begun in the southern Comoros islands of Nzwani and Mayotte. In these political conflicts, deposed Comorian elites were often the initiators of the invasions (eg Bwana Combo) and were also the leaders of Sakalava fleets (eg Sicandar and Nassiri), and given the combination of the Comorian elites' trans-regional alliances and the pre-existing custom of compensating mercenaries with captives and loot, a spill-over of the conflict across the East African coast was inevitable. He thus concludes that the Sakalava invasions were rooted more in the political rivalries of the Comorian and Swahili coastal states than in the slave trade of the western Indian ocean25. As one oral tradition recorded in Comoros states;

"People say that the invaders were Betsimisaraka and that they pushed their expeditions up to the East African coast, and that they were piloted by some people from Comoros, Zanzibar and the coast of Africa, who would only have been common law prisoners driven from their country."26

Panorama of Majunga, showing outrigger canoes and foreign ships

More than 1,000 years ago, settlers from the Swahili coast established dozens of cities on Madagascar's north-western coast, constituting some of the earliest permanent settlement of Africans on the island

Read about it here;

The Comoro Islands in Indian Ocean Trade before the 19th Century by Malyn Newitt pg 156-157)

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea by Iain Walker pg 76)

The Worlds of the Indian Ocean by Philippe Beaujard pg 557-563, 584-589)

Tom and Toakafo: The Betsimisaraka Kingdom and State Formation in Madagascar, 1715-1750 by Stephen Ellis 444-445, The Cambridge History of Africa. Volume 5 pg 396

Tom and Toakafo: The Betsimisaraka Kingdom and State Formation in Madagascar, 1715-1750 by Stephen Ellis pg 451-453)

Yankees in the Indian Ocean by Jane Hooper, Feeding Globalization: Madagascar and the Provisioning Trade by Jane Hooper

Madagascar and Mozambique in the nineteenth century by Edward A. Alpers pg 150)

Africa and the indian ocean world by G. Campbell pg 131

The worlds of the Indian ocean Vol2 pg Philippe Beaujard pg 558-559, 612-615

Feeding Globalization: Madagascar and the Provisioning Trade by Jane Hooper pg 161)

Domesticating the world by Jeremy Prestholdt pg 26, Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea by Iain Walker pg 76-78)

The Comoro Islands: Struggle Against Dependency in the Indian Ocean by M. D. D. Newitt pg 22)

Feeding Globalization: Madagascar and the Provisioning Trade by Jane Hooper pg 160-161

Madagascar and Mozambique in the nineteenth century by Edward A. Alpers pg 38-39)

Madagascar and Mozambique in the nineteenth century by Edward A. Alpers pg 48-49, 40)

Feeding Globalization: Madagascar and the Provisioning Trade by Jane Hooper pg 162-3, Madagascar and Mozambique in the nineteenth century by Edward A. Alpers pg 40-41

Feeding Globalization: Madagascar and the Provisioning Trade by Jane Hooper pg 163, Madagascar and Mozambique in the nineteenth century by Edward A. Alpers pg 42)

Trade, Society, and Politics in Northern Mozambique, C. 1753-1913 by Nancy J. Hafkin pg 175

Madagascar and Mozambique in the nineteenth century by Edward A. Alpers pg 43-44)

Madagascar and Mozambique in the nineteenth century by Edward A. Alpers pg 45)

Africa and the indian ocean world by G. Campbell pg 215, Madagascar and Mozambique in the nineteenth century by Edward A. Alpers pg 46-47

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea by Iain Walker pg 76, The Comoro Islands: Struggle Against Dependency in the Indian Ocean by M. D. D. Newitt pg 21)

The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century By William Gervase Clarence-Smith pg 186).

The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century By William Gervase Clarence-Smith pg 170-173, 183).

Madagascar and Mozambique in the nineteenth century by Edward A. Alpers pg 50-53, also see Jane Hooper’s “An Empire in the Indian Ocean: the Sakalava Empire of Madagascar”

Madagascar and Mozambique in the nineteenth century by Edward A. Alpers pg 52

> The island of Nzwani was home to the most prosperous kingdom in the Comoros archipelago during the 18th century, having grown as a major port-of-call for European ships which were provisioned and taxed at its main port of Mutsamudu.

I really dig your African History blog for I know next to nothing about Africa at all. It had almost no part in history in school in the 80s in the German Democratic Republic where I came from. And with most later historical books I either focussed on mostly non-African topics like WWII or Africa wasn't even mentioned. One reason for that is Africa was presented as a backwater of Europe, but other continents, too.

So when I heard of an African king who went to Mecca and while he went there, made the gold price fluctuate wherever he came through because he carried so much gold with his travelling entourage, it dawned on me that Africa wasn't so much behind, but just different and later on, colonialized which often means one's own history is deleted. Here you mention now "the most prosperous kingdom": what does this mean? How does it compare to other places, or how does it stand out from its neighbours, exactly?