Between Africa and India: Trade, Population movements and cultural exchanges in the Indian ocean world

African and Indian interactions during the medieval era of globalization

The Indian ocean world was a dynamic zone of cultural, economic and political exchanges between several disparate polities, cities and societies on the Afro-Eurasian world whose exchanges were characterized by complex, multi-tired and shifting interactions conducted along maritime and overland routes; communities of artisans, merchants, pilgrims and other travelers moved between the cosmopolitan cities along the ocean rim, hauling trade goods, ideas and cultural practices and contributing to the diverse “Indian ocean littoral society”. Despite this their long history of connections, contacts between Africa and the Indian subcontinent have often been overlooked in favor of the better known interactions between Africa and the Arabian peninsular, ignoring the plentiful documentary and archeological evidence for the movement of traders, goods and populations between either continents as early as the 1st millennium AD; in this reciprocal exchange, Africans in India and Indians in Africa established communities of artisans, soldiers, merchants and craftsmen and contributed to both region’s art and architecture, and played an important role in the politics and economies of the societies where they settled.

Studies of the “Indian ocean history” have revealed the complex web of interactions predating the era of European contact as well as highlighting connections between India and Africa that had been overlooked, but these studies have also shown the limitations of some of their theoretical borrowings from the studies of other maritime cultures (especially the Atlantic and Mediterranean worlds), such as the application of the world systems theory in the Afro-Indian exchanges, that positions India as the “core”, African coastal cities as the “semi-periphery”, and the African interior as the “periphery”; recent studies however have challenged this rigid “core–periphery” framework, highlighting the shared values, aesthetics, and social practices between the two regions and revealing the extensive bi-directional nature of the trade, population movements and cultural influences between Africa and India 1

This article explores the history of interactions between eastern Africa and the Indian subcontinent focusing on trade, population movements, architectural influences and other cultural exchanges between the two regions from late antiquity to the modern era.

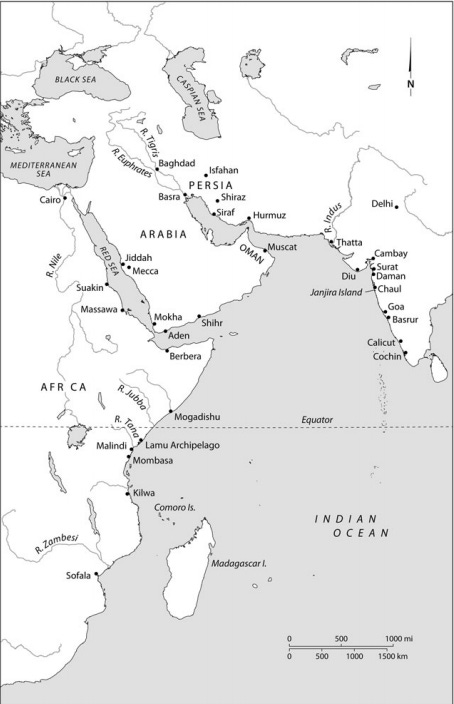

Map of the western Indian ocean showing some of the cities mentioned in the article

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The movement of merchants, ships and trade goods between Africa and the indian subcontinent from antiquity to the early modern era

African trade to the Indian subcontinent

The earliest direct contacts between the Indian subcontinent and Africa seem to have been initiated from the African side2; the Ethiopian empire of Aksum with its extensive maritime trading interests and its conquests of southern and western Arabia sought to dominate the important red sea conduit of trade between India and the Roman empire at the turn of the 3rd century AD, while little documentary evidence has come to light on direct travel of Aksumite or Indian ships to either's ports at this early stage, the existence of a late 2nd century stupa from Amravati in India, depicting the Satavahana king Bandhuma receiving presents from Aksumite merchants3 attests to early contacts to india from Aksum.

By the early 6th century, the chronicler Cosmas Indicopleustes describes at length the operation of the Indo-Roman trade in silk and spices in which Aksum was the main middleman, with Aksumite ships and merchants sailing from the Aksumite port of Adulis to the island of Sri lanka, paying for Indian (and Chinese) silk and spices with Aksum’s gold coinage as well as exchanging these for roman items such as amphorae, the Aksumite merchants then shipped this cargo to the Roman controlled port cities such as the Jordanian port of Aila (Aqaba) where 6th century writer Antoninus of Piacenza wrote that all the "shipping from Aksum and Yemen comes into the port at Aila, bringing a variety of spices" as well as to the Romano-egyptian port of Berenike where a significant Aksumite community resided4.

There is however, plenty of evidence that direct trade from Aksum to Sri lanka and the rest of the Indian subcontinent was already well established before the time of Cosmas’ writing, besides the direct request by emperor Justianian to the Aksumite emperor Kaleb for the latter to instruct his merchants to purchase more Indian cargo for the roman market5; evidence of Aksum-India trade includes; the presence of Aksumite coins in the India particularly at Mangalore and Madurai dated to the 4th and 5th century, as well as at Karur in Tamil Nadu, and the 3rd century Kushan coins recovered from Debre Damo in Ethiopia6; the substitution of the direct route between Rome and India by the 2nd century in favor of a multi-stage route from Sri-Lanka to the Aksumite port of Adulis to the Mediterranean7; this multi-stage route via Adulis can be seen in the travels of Scholasticus of Thebes (d. 360), Palladius (d. 420) and Cosmas Indicopleustes (d. 550)8, showing that that the Aksumite trade with India was well established by the 4th century and likely earlier.

The decline of Aksum after the 7th century and its withdraw from the maritime trade, saw the rise of the Dahlak island polity in the late 10th century, this Dahlak sultanate was essentially an Aksumite offshoot dominated by Ethiopian slave soldiers, its political activities were mainly concentrated in Yemen where it eventually conquered the city of Zabid and ruled the country for a little over a century as the Najahid dynasty (1022-1158), evidence that the Najahid commercial interests extended to India can be gleaned from the escape of prince Jayyash (one of the Najahid royals) to India where he lived as a Islamic scholar before his return to Zabid in 10899.

Foreign merchants (including Aksumites in the bottom half) giving presents to the Satavahana king Bandhuma, depicted on a sculpture from Amaravati, India

the ruins of Aksum in ethiopia

In the medieval and early modern era, indirect and direct trade contact between India and the horn of Africa was maintained through the sea ports of Zeila, Berbera and Massawa as well as the islands of Dahlak and Sorkota, while direct references to Indian imports to Ethiopia and Ethiopian exports to India are scant before the 16th century they include a mention of Indian silks bought by ethiopian King Zara Yacob (r. 1434-1468), trade between the two regions increased by the early 16th century when King lebna Dengel (r. 1508-1540) is mentioned to have been receiving silk and cotton cloths from India as tribute from his coastal governors on the red sea coast.

Several portuguese writers such as Tome Pires, Miguel de Castanhoso and Alvares also mentioned that Ethiopia exported gold to India in exchange for cotton from Cambay (both raw and finished) and that ethiopian churches were decorated in Indian silks, in the 17th and 18th century (during the Gondarine era), the import of Indian textiles grew significantly and Ethiopian nobles are known to have decorate the interiors of their churches with Indian cloths eg empress Mentewab's qweqwam church that was lavishly covered with curtains from surat, Indian clothing styles also became influential in the Gondarine art of the era complementing its cosmopolitan style that incorporated designs from a diverse range of visual cultures .10

Narga Selassie monastery wall paintings in the second gondarine style , an 18th century painting of Mary and child with empress mentewab (at the bottom) all wearing richly colored silk and brocade robes from india.11

In the 19th and early 20th century, a significant amount of trade passing through the red sea area, the gulf of Aden and the horn of Africa was dominated by Indian merchants especially in the importation of gold and ivory from Ethiopia that were exchanged for spices and textiles. Most of these traders supplied goods from Bombay and Malabar in the western half of the Indian subcontinent as well as from Bengal, many settled in the eastern African ports such as; the Somali city of Berbera, that is said to have been visited by about 10-12 indian ships from Bombaby which supplied over 300 tonnes of rice, 50 tonnes of tobacco, as well as about 200 bales of cloth annually, exchanging it for African ivory amounting to 3 tonnes, and while the Horn of Africa's domestic cloth production was significant, many of the people also wore cloth from India that was reworked locally to supplement the domestically produced textiles.

The Somali cities of Mogadishu, Merca and Kismayo were home to several itinerant Indian merchants active in the cities’ trade with similar trade goods ast in Berbera, especially rice and textiles, a number of the Indian traders in these ports were agents of the Zanzibar-based sultans of Oman. The eritrean city of Massawa was home to a few dozen indian merchants, and on top of the usual trade items such as the 500 kg of gold a year exported from ethiopia and around 108,000 pounds of cotton, these indian merchants were also engaged in money lending, some were also craftsmen involved in shipbuilding, but their population remained small with no more than 80 resident in the city in the late 19th century.

By 1902, imports to the italian colony of eritera from india still totaled over 3.1 million lire about 40% of all imports before falling to 20% by the end of the decade. In the ethiopian interior, significant quantities of raw cotton from india were imported which was then spun locally for domestic markets, indian spices and indian furniture were also imported, the indian community numbered a few dozen in Harar and Addis in the late 19th century but were nevertheless an important group in the domestic market's foreign trade (although much of the domestic trade was in local hands) by the 1930s, the indian community in ethiopia had grown from round 149 in 1909 to about 1,700 in 1935 and there were atleast 100 trading houses in the capital owned by indian merchants12

Indian house in Addis Ababa likely belonging to a merchant (mid 20th century photo)

Trade between the Swahili city-states and the Indian subcontinent

The Swahili city-states of eastern Africa were in contact, either directly or indirectly, with the Indian subcontinent from the 7th century AD, this stretch of coast whose urban settlements emerged in the mid 1st millennium from bantu-speaking Swahili communities, had long been incorporated into Indian Ocean networks of trade and was widely known as an exporter of luxuries to the Arabian Peninsula and the Persian Gulf, and onward to markets in India and China. In the 10th century, Al-Mas’udi reports that the people of East Africa were exporting ambergris and resins, leopard skins, tortoise-shell, and ivory, the last of which were highly prized in the workshops of India and China as it was easier to carve that the local alternatives, al-Biruni (d. 1030) mentions that the port of Somanatha in Gujarat, India became famous "because it lay between Zanj (swahili coast) and China" as the main trading port for east African commodities especially ivory, Al-idrisi (d. 1166) also mentions that east African iron was exported to India in significant quantities from the region of sofala (a catch-all term for the southern Swahili coast in Tanzania and northern Mozambique).13

Swahili traditions also preserve early connections with merchants from the kingdom of sindh (in southern-Pakistan, northen-India), they mention the waDebuli (or waDiba) which were ethnonyms associated with a range of historical events and periods in different parts of the Swahili coast in the city-states of Pemba, Zanzibar, Kilwa, and Mafia and refer to a direction of cultural contanct between the Swahili and the port of Debal/Daybul in pakistan (perhaps the site of Banbhore), or Dabhol in india. The dubious nature of this tradition however, which involves the typical telescoping and conflation of once separate histories that is commonly found in swahili acounts makes it difficult to interpret the Sindh-Swahili relationship with certainty, and while Daybul features prominently in Arab and Persian texts as one of the important cities in the Sindh kingdom between the 9th and the 13th centuries, its yet to be identified on ground conclusively.14

In the city state of Kilwa, there is mention of a Haj Muhammad Rukn al-Dabuli and his brother Faqih Ayyub who were in charge of the city’s treasury when the Portuguese had arrived in 1502, al-Dabuli was installed by the Portuguese but later killed by rival claimants, his nisba (al-Dabuli) suggests that both him and his brother traced their ancestry to Daybuli, but it may as well be a pretentious connection similar to the usual al-Shirazi nisba in most indigenous Swahili names.15

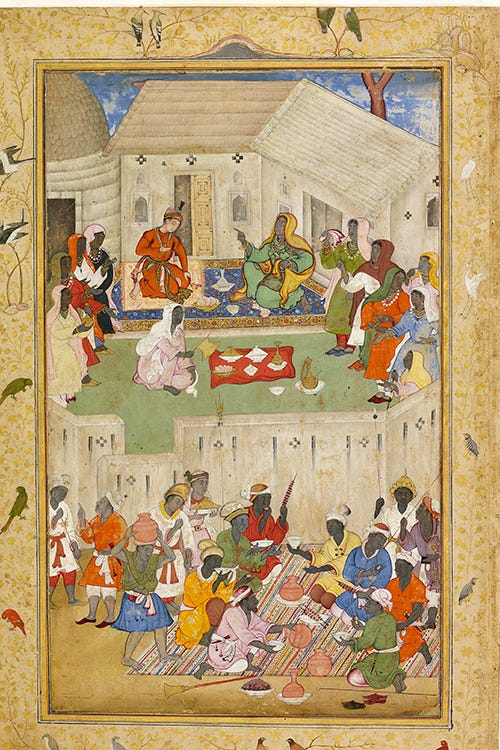

Representation of an Indian prince eating in the land of the Ethiopians or East Africans (Zangis). Mughal, Akhbar period, c. 1590. Museum Rietberg Zurich

Ruins of the Swahili cities of Kilwa and Songo Mnara in Tanzania

Indian artisans may have also been present on the early Swahili coast, the bronze lion figurine dating from the 11th century found at shanga, while modeled on an African lion was stylistically similar to the range of lion figurines in the deccan region of western India, a few of the early kufic inscriptions on the coast may have also been carved by these Muslim Indian artisans; at least one architectural feature from Kilwa was most certainly taken from Hindu temple16 although Swahili architecture displays little, if any, Indian influences, and there seems to have been little direct contact or settlement between India and the Swahili coast before the late 15th century.17

A significant trade in glass beads made in India is attested at various Swahili cities although these are most likely derived from trade with the Arabian peninsular, and the Swahili also engaged in secondary manufacture of raw Indian glass especially at the site of Mkokotoni on Zanzibar where large quantities of glass waste, molten glass and several million glass beads were found, the site was a huge depot for finishing off sorting and distribution of Indian trade beads.18 A small but salient influence of sidh coinage can be seen in Swahili coins especially the silver coinage from Shanga which shares a few characteristics similar to coinage excavated at the site of Banbhore indicating some sort of contact between the two regions albeit minor19.

A substantial trade in grain was noted from the Swahili cities that supplied parts of India and Arabia, in particular; the cities of Mombasa and Malindi are known to have grown wealthy supplying Indian, Hadrami-Arab, and other Red Sea ships with millet, rice, and vegetables produced on their mainland, as well as fruits grown on the island itself.20

Bronze lion from the city of Shanga

architectural element from the Kilwa sultan’s Mausoleum (Berlin museum)

Mombasa beachfront in the 1890s

While the vast majority of cloth along the Swahili coast was manufactured locally especially in the cities of Pate and Mogadishu, a significant trade in Indian cloth developed by the 15th century, especially with imports from Gujarat. In 1498, Vaso Dagama located Gujarat indians resident in the cities of Malindi and Mombasa and used the services of one of them, Ibn Majid (a confidant of the Swahili sultan of Malindi) to guide his fleet to western india from Malindi to Calicut, Tom Pires (1512-1515) also described trade between Khambhat in the gujarat region and the swahili cities of Kilwa, Malindi and Mogadishu that included rice, wheat, soap, indigo, butter, oils and cloth, in 1517-18, Duarte Barbosa noted great profits made by these Khambhat merchants especially in cloth, he also recorded Gujarat ships at Malindi and Mombasa, mentioning that the “presence of Gujaratis in East Africa was neither unusual nor new”21 however, no significant Indian community is attested locally whether in recorded history or archeology and most writers note that the itinerant Indian traders "were only temporary residents, and held much in subjection”.22

Gujarati ships are said to have bought "much ivory, copper and cairo (rope manufactured on the coast)" as well as gold and silver, from the swahili merchants from the cities of Malindi, Mombasa. These Swahili cities also sent ships to Gujarat, the most notable being Pate as was ecorded in the pate chronicle, when the ruler of Pate Mwana Mkuu is mentioned to have sent several swahili ships to Gujarati for cloth23, by 1505, Tome Pires noted the presence of several eastern African merchants from ethiopia, Mogadishu, Kilwa, Mombasa and Malindi in Malacca in Indonesia, its likely that many would have been trading directly with India by that time as they are mentioned to have used Gujarat as a transit point.24

The Swahili were re-exporting much of the Gujarati cloth and the Cambay cloth into the African interior where it supplemented the existing cloth industries in the Zambezi and Zimbabwe plateau.25 In the early 16th century, a Swahili merchant bough 100,000 Indian cloths from Malindi to Angoche where they was traded throughout the Zambezi valley, between 1507 and 1513, 83,000 Gujarati cloths were imported into Mozambique island from India, by the mid 17th century, an estimated 250 tonns of Gujarati cloth was entering the eastern african region annually including the swahili coast, the Comoro islands and Madagascar with annual imports exceeding 500,000 pieces most of these textiles were exchanged for ivory and gold26, despite this large volume of trade, east African cloth manufacture continued virtually unabated in most regions and flourished in the 19th century Zanzibar as a result of it.27

the Comorian city of Moroni in the early 20th century

Population movements between the Indian subcontinent and Africa

African population movements to India

While a significant number of Africans in the Indian subcontinent came as merchants and travelers, and as already mentioned itinerant east African traders were active in most of the western Indian ocean and temporarily resided in some regions such as Gujarat and like their Indian counterparts in Africa, the numbers of these African traders were small and are effectively archeologically invisible, save for the exceptional case of southern Arabia where a large African community of (free) artisans is distinctively archeologically visible in the city of Sharma, an important transshipment point between the 10th and 12th century28 , the bulk of the population of African descent arrived as enslaved soldiers seemingly via overland routes through arabia but also some came directly from overseas trade.

African slaves were however, outnumbered in India for long periods by Turkic slaves originating from Central Asia and never made up a significant share of the enslaved population in (islamic) India which also include Persians, Georgians and other Indian groups.29The majority of the african slave soldiers were also male and many were assimilated into the broader Indian society, marrying local women (often those from Muslim families) to the extent that, as one historian observed and geneticists have recently confirmed "its rare to find a pure siddi"30, a number of enslaved women also arrived near the close of the trade in the early 19th century31

The vast majority of the siddis served as soldiers and some rose to prominent positions in the courts of the Deccan sultanate with some ruling independently as kings, the figures often given in Indian texts, of these enslaved Africans should be treated with caution considering the comparably small numbers of slaves that were traded in the 18th and 19th century at the height of the slave trade. The various names given to the African-descended populations on the Indian subcontinent is most likely related to their places of origin, initially they were called Habashi or Abyssinian which is an endonym commonly used in the horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia), this was probably in use in the first half of the 2nd millennium, by the late 16th century, they were referred to in external texts as Cafire, a word used by the Portuguese and derived from the Swahili (and also Arabic word) Kaffir (non-believer) used to refer to the non-Muslim inhabitants of the interior of south-east Africa, the term Siddi was popularized during the British colonial era in the 19th century and remains in general use today, it was originally a term of honor given in western Indian sultanates to African Muslims holding high positions of power and is said to have been derived from syd (meaning master/king in Arabic).32

While they are commonly referred to as “Abyssinian”, “Habashi” or even “Ethiopian” in various texts, studies on their genetic ancestry reveals that the siddi were almost entirely of south-east African origin, with some Indian and Portuguese genetic admixture but hardly any from the horn of africa33, and because of this, I'll use the generic term Siddi rather than Habshi/Abyssinian unless the ancestry of the person is well known.

The earliest among these prominent siddi was Jamal-ud-Din Yaqut who lived between 1200-1240, serving as a soldier of high rank in the Delhi sultanate then under the reign of Iltutmish (r. 1211-1236), the latter was a turkic slave who became the first ruler of the Delhi sultanate, his daughter Raziya succeeded him in 1236 and ruled until 1240, throughout her short ruler, Yaqut was her closest confidant and the second most powerful person in the kingdom, but his status as a slave and an African close to the queen was resented by the turkic slave nobility who claimed the queen was in love with Yaqut and feared Yaqut's intent to seize the kingdom himself, they therefore overthrew the queen and ambushed Yaqut's forces, killing him in 1240 and killing Razia herself a few weeks after.34

In the Bengal sultanate, the Indian ruler Rukh-ud-Din Barbak (r. 1459-1474) sought to strengthen his army with slave soldiers of various origins (as was the norm in the Islamic world where European, African, Turkic, Persian and Indian, who were used to centralize the army more firmly under the king's rule), he is said to have purchased a bout 8,000 african slaves, these slaves occupied very privileged positions and soon became king makers and kings themselves, As Tome Pires wrote

“The people who govern the kingdom [Bengal] are Abyssinians. These are looked upon as knights ; they are greatly esteemed; they wait on the kings in their apartments. The chief among them are eunuchs and these come to be kings and great lords in the kingdom. Those who are not eunuchs are fighting men. After the king, it is to this people that the kingdom is obedient from fear.”35

The first siddi to rule the Bengal sultanate was Shahzada Barbak who ruled in 1487 who was originally a eunuch, he was after a few months overthrown by another siddi, Saifuddin Firuz Shah (Indil Khan) who was formerly the head of the army but was supported by the elites of the sultanate, he ruled until 1489 and is credited with a number of construction works including the Firuz Minar in west Bengal, he was succeeded by Shams ud -din Muzaffar Shah in 1490 shortly after the latter had killed the rightful heir who had assumed the throne after Firuz Shah’s death, he ruled until 1493 and is said to have possessed an army of 30,000 with atleast 5,000 siddis, but his reign wasn't secure and he was overthrown by local forces, the rebellious but powerful siddi army was disbanded by later sultans of Bengal and it dispersed to the neighboring kingdoms of Bijapur and Ahmadnagar in the 15th and 16th centuries.

In Bijapur, the various slave officials and soldiers from across many regions jockeyed for power and at one point a Georgian slave official who served as governor threatened other siddi slave governors with a decree prohibiting Deccanis and Habashis from holding office in 1490 but by 1537, this was policy was later reversed and the siddis were active again in Bijapur’s court politics one of these was Siddi Raihan who formed a siddi party and served as chief advisor of ibrahim Adil shah II (r. 1580-1627) and as regent of his son, who later assumed power as Muhammad Adil Shah (r. 1627-1656), the latter was then served by Siddi Raihan as prime minister and he was given the name Ikhlas Khan.

Throughout this time Ikhlas Khan was in charge of the state's finances and adminsitration until 1686 when Bijapur fell to the mughals. There were several other outstanding generals and govenors of African descent active in Bijapur during this time including Kamil Khan, Kishwar Khan, Dilawar Khan, Hamid Khan, Daulat Khan (known as Khawas Khan), Mohammad Amin (known as Mustafa Khan), Masud Khan, Farhad Khan, Khairiyat Khan and Randaula Khan (known as Rustam -i Zaman), the last one in particular, oversaw the the silk producing southwestern provinces of Bijapur bordering the Portuguese colony of Goa, another was Siddi Masud who served as regent of the last sultan of Bijapur Sikandar Adil Shah (r. 1672 -1686) and is credited with patronizing arts, as well as undertaking several constructions such as Jami Masjid in 1660 and establishing the townships of Imatiazgadh and Adilabad, he retired in 1683 and ruled in Adoni province until surrendering to the mughals in 1689.36

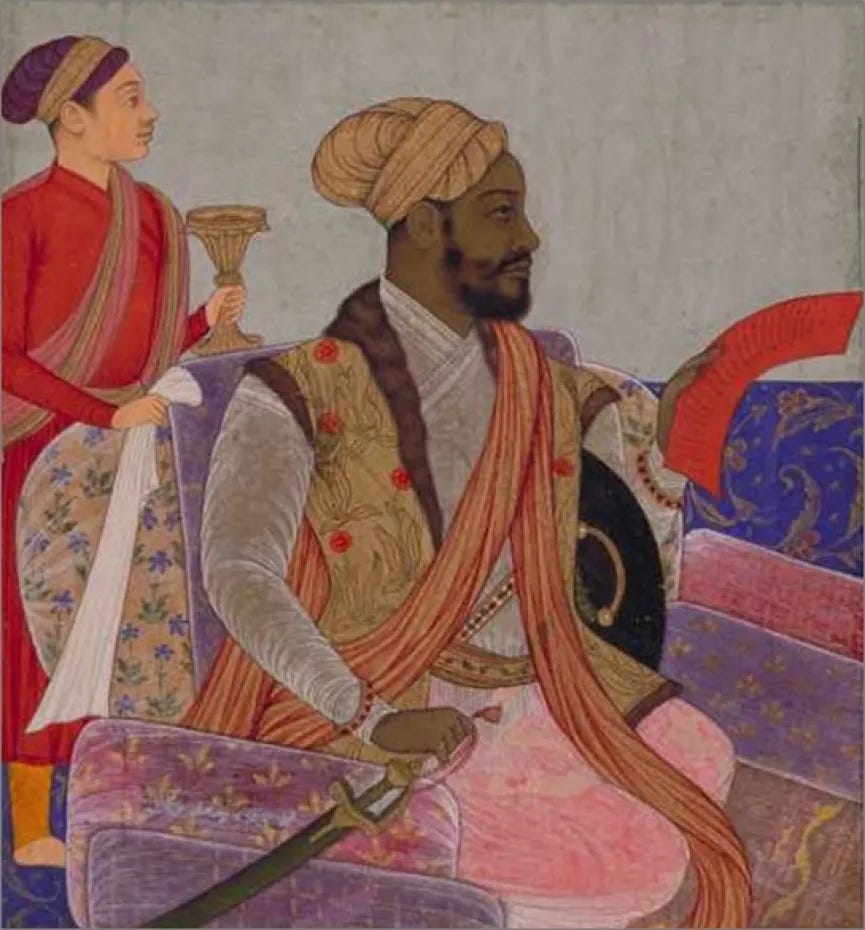

Sultan Muhammad Adil Shah of Bijapur and African courtiers, ca, 1640.

Ikhlas Khan with a Petition ca. 1650 (San Diego Museum of Art)

Ikhlas Khan and his son and successor, Muhammad Adil Shah. (San Diego Museum of Art)

In the sultanate of Ahmadnagar, several Siddis rose to prominence but the most famous was the Abyssinian general Malik Amber who was born in Harar in 1550, and passed through several slave owners in africa and arabia where he was educated in administration and finance, he was then purchased by a minister in the Ahmadnagar sultanate, he was later freed and briefly served in Bijapur before returning in 1595 serving under the Siddi prime minister Abhangar Khan, he fought in the succession disputes of the Ahmadnagar sultanate and installed Murtaza Nizam Shah II as a boy-King in 1602 and reigned as his regent effectively with full power, he also defeated several Mughal incursions directed against Ahmadnagar, he later replaced Murtaza II with a lesser rebellious puppet Nizam Shah Burhan III (r. 1610-1631) allowing him to attain even more control as the most powerful figure in the sultanate as well as the entire western india region, with an army of 60,000 that included persians, arabs, siddis, deccani Muslims and Hindus. Upon his death in 1626, one chronicler wrote;

"In warfare, in command, in sound judgment, and in administration, he had no rival or equal. He kept down the turbulent spirits of that country, and maintained his exalted position to the end of his life, and closed his career in honour. History records no other instance of an Abyssinian slave arriving at such eminence".

Ambar was succeeded by his son Fath Khan who reigned until 1633 when he surrended to the Mughals along with his puppet sultan Husain III ending the state's independence. Shortly after its fall however, the emerging Maratha chieftains had crowned another sultan Murtaza III on the Ahmadnagar throne hoping to preserve the state but his reign was shortlived, the primary force during Ambar's rule, besides an alliance with the siddis of Janjira fortress, seems to have been an alliance with the emerging Maratha state, and the actions of Malik Ambar helped maintain the independence of Amadnagar making the state "the nursery in which Maratha power could grow, creating the political preconditions for the eventual emergence of an independent Maratha state".37

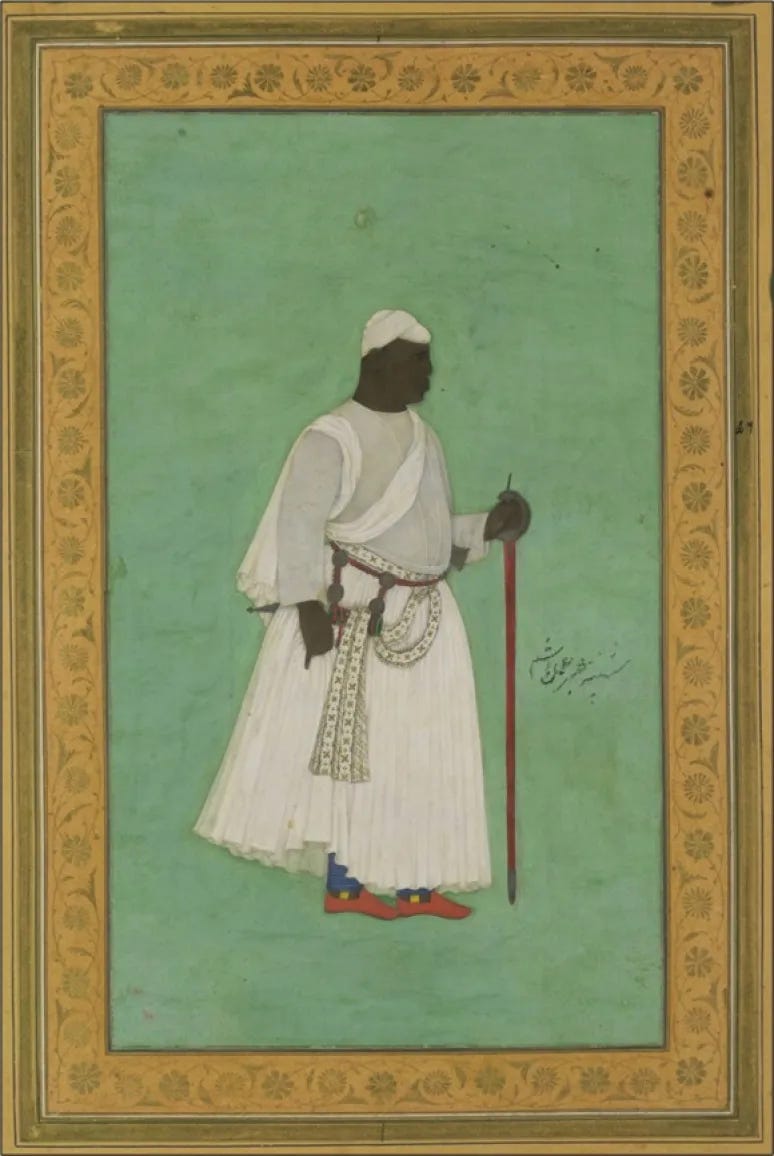

Portrait of Malik 'Ambar early 17th century (Victoria and Albert Museum)

The tomb of Malik Ambar, Khuldabad, ca. 1625

The institution of diverse slave contingents wasn't continued by the Mughals and the presence of the Africans in India was diminished although some imports continued to trickle in some semi-independent regions as well as those controlled by the Portuguese, The last stronghold of the siddis remained the janjira fort, built by the siddis in the 15th century as the home of an independent Siddi state whose rulers were initially appointed as commanders of the fortress by Malik Ambar, the state lasted until the 20th century, it resisted several Mughal, Maratha and British sieges throughout the 16th-18th century and was ruled by a Siddi dynasty who also extended their power to parts of the mainland where they constructed a necropolis complex for their rulers.38

In Wanaparthy Samsthanam (a vassal of the Hyderabad kingdom), the Raja Rameshwar Rao II (1880-1922) is said to have constituted a cavalry and bodyguard force of siddis, because of their mastery in training horses and trustworthiness, they later became part of the regular forces of the Nizam of Hyderabad in the early 20th century, only being disbanded by colonial authorities in 1948. 39 In the kingdom of Awadh, the last king Wajid Ali Shah had several soldiers of African decsent in his guard including women, his second wife queen Yasmin was a siddi, his siddi soldiers were part of the armies that faced off with the British in 1856 40. Other prominent siddis include Yaqut Dabuli, a prominent siddi architect of Sultan Muhammad Adil Shah (r. 1627 -1656), who was responsible for elaborate color decoration of the great mihrab in the Bijapur Jami Masjid.41

Yasmin Mahal wife of wajid ali shah 1822-1827 the last king of Oudh in uttar Paradesh

Tombs of; Siddi Surur Khān (d. 1734), Siddi Khairiyāt Khān (d. 1696) and Siddi Yāqut (born Qāsim Khān, d. 1706) in Khokri on the mainland near the Janjira fortress42

In the Portuguese era between the late 16th and early 19th century, a small but visible level of slave trade existed between their southern Indian and eastern African colonies, the Portuguese presence in India was established at Goa in 1510, Diu in 1535, Daman in 1559 and Nagar Haveli in 1789, but it was the first three where most African trade was directed primarily involving ivory, gold and slaves the last of whom were mostly from south-east Africa but also from the horn of africa where the Adal-Abbysinia wars and the Portuguese predations along the Somali coast had resulted in a significant number of slaves being sold into the Indian ocean market in the 16th century, but from the 17th-the early 19th century, the bulk of slaves came from the Mozambique coast.43 while the vast majority (over 90%) of the Mozambique slaves were shipped to brazil, a few dozen a year (an average of around 25) also went to the cities of Diu, and Daman, while around 100 a year were sold to Goa, the lowest figure being 3 slaves in 1805 and the highest were 128 slaves in 1828 for the entire region.44

Population movement from the Indian subcontinent to Africa.

While many Indians arrived in east Africa as merchants and travelers as already mentioned, their numbers were relatively small in most parts well into the 19th century, compared to these pockets of settlements in east african cities, the bulk of Indians on the east African coast arrived as slaves during the 18th and early 19th century, almost all were confined to the islands of Mauritius and Reunion, their populations were latter swelled by Indian workers (both free and forced labour) that arrived during the colonial era in the late 19th century.

By the 18th century, a large number of enslaved Indians were present in some of the Portuguese and French controlled east african coastal islands especially the Mascarene islands such as the islands of Reunion and Mauritius where roughly 12% of the 126,000 slaves in 1810 were of Indian descent, (with Malagasy slaves making up about 45% and south-east African slaves making up about 40% and the rest drawn from elsewhere)45 in 1806, the over 6,000 Indian slaves on Mauritius constituted around 10% of the island’s population and by 1810, enslaved Indians in Mauritius numbered around 24,000.46

Unlike the African slave soldiers of the Deccan, these enslaved Indians (as well as their Malagasy and African peers) couldn’t rise to prominent positions in the plantation societies; a pattern which was characteristic of European slave plantations elsewhere in the Atlantic world. This Indian slave trade ended in the mid 19th century when all slave exports above the equator were banned, despite the ban however, a significant trade in slaves from the Indian subcontinent continued especially from balochitsan region; one that lasted well into the early 20th century to an extent that it replaced the east African slave trade entirely, meeting the slave demand of the Omani sultanate whose capital was Zanzibar47, these Balochi slaves were almost exclusively employed as soldiers for the Omani sultans of Zanzibar and numbered several hundred in the 19th century.48 but a significant number of the Balochi slaves also included women who served various household tasks, as well as other slaves from other parts of the Indian subcontinent that were also used in the Zanzibar clove plantations.49

By the 19th century, a significant proportion of Indian merchants that included Banyans and Khojas begun to settle in Zanzibar following the Omani sultans' conquests along the Swahili coast, the movement of these Indian merchants was based on the long-standing relationships that the Omani sultans had with them while in southern arabia,50 their population is estimated to have been around 1,000 in 1840 and between 2,000-6,000 in 1860 (although scholars think these figures are likely exaggerated even if they represented the entire east African domain of the Zanzibar sultanate)51 The Indian merchants’ importance in local trade was such that upto 50% of imports to Zanzibar consisted of Surat clothes, as well as 50 tonnes of iron bars, sugar, rice and chinaware imported annually from Bombay, Surat and Muscat.52

The Zanzibar-based Banyans also provided credit as money lenders to the handicraft industries, to merchants travelling into the interior for ivory as well as those active in the city’s markets, but they didn't engage much in the plantation agriculture of zanzibar53, The indian merchants became particularly skilled in this field of finance such that in the late 19th century, the Zanzibar sultan Majid was heavily indebted to several Indian merchant houses, eg the Kutchi House demanding about $250,000 while the Shivji Topan House demanded upto $540,000, these debts had been previously paid in kind by the sultans in the form of reciprocal commercial and protection rights in the Omani ruler’s territories but as the Zanzibar sultanate increasingly came under British rule, the latter forced the Omani sultan to quantify the figure however arbitrary54

By 1913, the number of Indians in colonial Tanganyika was around 9,500 although the vast majority of them were contractual laborers brought in by the colonial government rather than descendants of the older populations, a similar trend was observed in Kenya where the vast majority came in the late 19th century and early 20th century as contractual laborers for the Uganda railway.55

The Ithna sheri Dispensary in zanzibar built in the late 19th century by Tharia thopan, an Indian Muslim trader from Gujarat, its construction combines Indian styles with swahili and European designs

Zanzibar beachfront in the early 20th century

Cultural exchanges between the Indian subcontinent and Africa

Indian architecture in Eastern Africa and Other cultural influences

As mentioned earlier, there was a small presence of Indian craftsmen in the eastern Africa since the early second millennium, in ethiopia beginning in the 17th century, a hybridized form of Ethiopian, indo-Islamic (Mughal) architecture developed in the capital of Gondar with increased contacts between the two regions, one notable Indian architect named Abdalkadir (also called Manoel Magro) is credited in local texts with making a new form of lime in the early 1620s and is said to have designed the castle of king Susenyos (r. 1606-1632) along with the Ethiopian master builder Gäbrä Krǝstos, this castle was the first among several dozen castles of the gondarine design56, emperor Fasilides (r. 1632-1667) is also said to have employed several Indian craftsmen after his expulsion of the Portuguese Jesuits, these craftsmen are said to have constructed his palace "according to the style of his country”57

A number of gondarine constructions incorporated Mughal styles, a noted example was the bath of Fasilides that in execution is similar to an Indian jal mahal (water palace), a common form of elite construction in northern India, this bath is traditionally credited to Fasilides but was likely built by emperor Iyasu II in the late 17th century.58

Fasilides’ bath in Gondar built in the 17th century

In the 19th and early 20th century, an influx of Indian craftsmen into ethiopia was encouraged by emperor Menelik (r. 1880-1913), most of them stayed in the capital Addis Ababa but some went to the city of Harar. The number of skilled craftsmen among these Indian immigrants was quite small numbering less than two dozen, with the vast majority of the estimated 150 indians in Ethiopia in 1909 being involved in foreign trade for which they are said to have successfully displaced the French and the Greeks who had been the leading foreign traders in the capital. Despite their small numbers, the Indian artisans of Menelik are nevertheless credited with some unique construction designs that fused Ethiopian and Indian architecture such as the works of the indian architects Hajji Khwas Khan and Wali Mohammed which include, the church of Ragu'el at Entoto built in 1883, the church of Elfen Gabriel in Addis Ababa, the church of Maryam at Addis Alam built in 1902, the palace at Holoto built in the 1900s, and the House of the cross at Dabra Libanos59.

Indian influence on the architecture of Ethiopia was however limited in extent not just by the small numbers of craftsmen but also the fact that few buildings display Indian styles, the general architecture of Ethiopia conforms to the broader domestic styles present in the region since the Aksumite and Zagwe era.

church of Ragu'el at Entoto

Other Indian architectural influences can be observed in some of the Indian-style constructions in the city of Zanzibar (most are occupied by people of Indian descent) as well as several of the elite house doors in a number of Swahili cities such as Lamu and Mombasa that incorporate Gujarat designs60

gujarati style door in Lamu

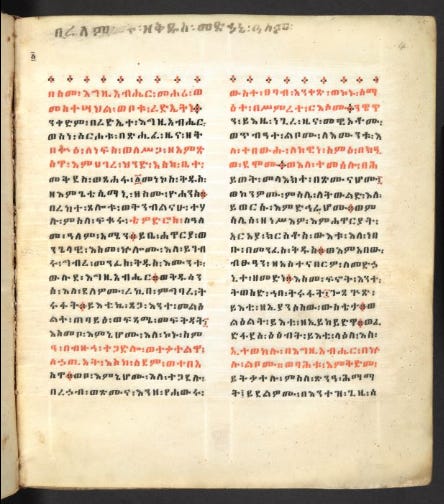

Other faint Indian influences in east Africa can be gleaned from the manuscript illumination styles of the eastern African coast especially in the cities of Harar and Zanzibar in the 18th and 19th century61, as well as the study of some Buddhist texts in Ethiopia.

Ethiopic Version of a Christianized story of the Buddha, from an 18th century Munscript Or. 699 (british library)62

African architecture in the Indian subcontinent and other African cultural influences in India

Architectural connections between siddi and African constructions can be drawn in the Siddi Sayed Mosque, built by the Ethiopian Siddi Sayed in 1570-71 in Gujarat which compares well with the numerous rock-hewn churches in northern Ethiopia, and the intricate lattice work in the arches of the Mosque that has parallels in the processional crosses of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Despite a few african parallels, siddi architecture in general and siddi funerary architecture in particular largely conforms to the indo-Muslim styles present in the Deccan region63

The Siddi Sayed Mosque in Ahmedabad, Gujarat; showing its intricate latticework

In the Khandesh sultanate (1382-1601), the practice of confining all possible successors of the reigning dynasty away from the royal court may have been a practice brought by the Habshi slaves in India, as it was already a well established royal custom in Christian Ethiopia in the early 14th century, although there were a few later Indian parallels to this custom making it difficult to determine its origin.64 The use of Amulets among the siddis is also a practice likely derived from the African mainland where they were ubiquitous among Muslim and non-Muslim and Christian (Ethiopian) communities, these talismans are believed to protect the individual from disease and misfortune.65

(SIDE-NOTE: the writings of the 18th century west African scholar Salih al-Fullani were very influential in India’s Ahl al-Ḥadīth school in the 18th and 19th centuries and his Indian students published a number of his books in India during the early 20th century, you can read more about him on my Patreon post)

Conclusion: Afro-Indian cultural exchanges beyond “cores” and “peripheries”

The history of contacts between Africa and the Indian subcontinent reveals the dynamic and complex nature of the cultural exchanges between the two regions, African goods, merchants, ideas and people moved to India as often as Indian goods, merchants, ideas and people moved to Africa, in an exchange quite unlike the unidirectional movement of people from Africa and goods from India as its often misconceived in Indian ocean historiography. The reciprocal nature of the trade also meant that far from the exploitative nature of exchange that characterizes the core-periphery hypothesis, manufactures from the Indian “core” such as textiles supplemented rather than displaced manufactures from the African “periphery” and there is indication that in some parts of the Swahili coast, Indian textile trade begun almost simultaneously with domestic manufacture in a pattern that continued well into the 19th century when Zanzibar was importing large amounts of yarn from india for local cloth industries.66

The influences of Indian and African immigrants on either continent has at times been overlooked especially in Indian historiography and other times been overstated especially in east African historiography in a pattern largely influenced by the current status of the African or Indian communities in either regions which is mostly a product of the colonial era as i’ve demonstrated with the population movements that after the late 19th century became rather asymmetrical with an influx of Indian laborers and merchants not matched by a movement of Africans of similar status into India while those populations of African descent were stripped of the relatively privileged status that they had in the pre-colonial kingdoms.

Indians of African descent certainly played a prominent role in western India especially between the 15th and 17th century but also in other parts well into the early 20th century despite the marginalized status of siddis in modern India, and Africans of Indian descent were also important in the foreign merchant communities of Africa and some craftsmen are credited with introducing Indian architectural styles in eastern Africa, although their influence has been attimes overstated in African historiography which is unmatched by their fairly small communities whose residents were itinerant in nature, and their confinement to foreign trade that made up a small proportion of the largely rural domestic economy, as the historian Randall Pouwels writes of both Arab and Indian immigrants on the swahili coast : “evidence overwhelmingly suggests that immigrants came to these societies almost always as minorities, and there are few indications prior to the late eighteenth century that immigrants succeeded in forcing the direction of change, which generally tended to be gradual and subtle and definitely given effect within the frame work of existing structures, values, and Institutions”67

A deeper study of the Indian ocean world that is free of reductive theoretical models and the hangover of colonial historiography is required to uncover the more nuanced and robust connections between Africa and the Indian subcontinent, inorder to understand the salient role Africans and Indians played in pre-modern era of globalization.

Download some of the books on India African relations and read more on Salih Al-Fullani’s influence in India on my patreon

see “India in Africa: Trade goods and connections of the late first millennium by Jason D. Hawkes and Stephanie Wynne-Jones” for a more detailed discussion of this

Aksumite Overseas Interests by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 138-139

Trade And Trade Routes In Ancient India By Moti Chandra pg 235)

The Red Sea region during the 'long' Late Antiquity by Timothy Power pg 45-47

The Indo-Roman Pepper Trade and the Muziris Papyrus by Federico De Romanis pgs 68

Cultural Interaction between Ancient Abyssinia and India by Dibishada B. Garnayak et al. pg 139-140

The Indo-Roman Pepper Trade and the Muziris Papyrus by Federico De Romanis pgs 67-70

The Red Sea region during the 'long' Late Antiquity by Timothy Power pg 84-85

A History of Chess: The Original 1913 Edition By H. J. R. Murray pg v

New Aspects of India's Influence on the Art and culture of Ethiopia pg 5-9, African Zion pg 194

“ Major themes in Ethiopian painting" by Stanisław Chojnacki pg 241-243

Indian Trade with Ethiopia, the Gulf of Aden and the Horn of Africa in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries pg 453-497

art orientalis 34, the arts of islam pg 66-67)

Deep memories or symbolic statements? The Diba, Debuli and related traditions of the East African coast by Martin walsh, Art orientalis the arts of islam pg 68

Indian relations with east africa before the arrival of the portuguese by Neville Chittick pg 119)

Indian relations with east africa before the arrival of the portuguese by Neville Chittick pg 122

Art orientalis 34, the arts of islam pg 66, 68)

Art orientalis 34, the arts of islam pg pg 72)

India in Africa: Trade goods and connections of the late first millennium, The Indian Ocean and Swahili Coast coins, international networks and local developments

Eastern africa and the indian ocean to 1800 by Randall L. Pouwels pg 399)

Art orientalis 34, the arts of islam pg 67)

Indian relations with east africa before the arrival of the portuguese by Neville Chittick pg pg 120)

As artistry permits and custom may ordain by Jeremy G. Prestholdt pg 11)

Indian relations with east africa before the arrival of the portuguese by Neville Chittick pg 121)

As artistry permits and custom may ordain by Jeremy G. Prestholdt pg 26-27)

the spinning world byPrasannan Parthasarathi pg 167)

Ocean of Trade by Pedro Machado pg 136-9, Twilight of Industry by Katharine Fredrick

Art orientalis 34, the arts of islam pg 77)

Between Eastern Africa and Western India by Sanjay Subrahmanyam pg 816)

The African Dispersal in the Deccan by Shanti Sadiq Ali pg 199-200)

Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia by Gwyn Campbell pg 25)

From Africans in India to African Indians by R Czekalska pg 193)

Unraveling the Population History of Indian Siddis by R Das

From Africans in India to African Indians by R Czekalska 196-198)

Between Eastern Africa and Western India by Sanjay Subrahmanyam pg pg 817)

From Africans in India to African Indians by R Czekalska pg 197-205)

A social history of the deccan by Richard M. Eaton pg 128)

The african dispersal in the deccan by Shanti Sadiq Ali pg 157-189)

The african dispersal in the deccan by Shanti Sadiq Ali pg 193-198)

From Africans in India to African Indians by Renata Czekalska pg 195

The african dispersal in the deccan by Shanti Sadiq Ali pg 137)

Memorials of Sovereignty: Funerary Architecture of the Siddis of Janjira at Khokri (Maharashtra) by Pushkar Sohoni

The african dispersal in the deccan by Shanti Sadiq Ali pg 202-219)

structure of slavery in indian ocean africa pg 19-20)

structure of slavery in indian ocean africa pg 35-37)

structure of slavery in indian ocean africa pg pg 41-43)

slaves of one master by by Matthew S. Hopper pg 183)

Makran, Oman, and Zanzibar by Beatrice Nicolini

The Swahili Coast by Christine Stephanie Nicholls pg 288

Trade and Empire in Muscat and Zanzibar by M. Reda Bhacker pg 12-13)

Indian Africa: Minorities of Indian-Pakistani Origin in Eastern Africa edited by Adam, Michel pg 103

Trade and Empire in Muscat and Zanzibar by M. Reda Bhacker pg 67)

Trade and Empire in Muscat and Zanzibar by M. Reda Bhacker pg 132-133)

Trade and Empire in Muscat and Zanzibar by M. Reda Bhacker pg 176-178)

Indian Africa: Minorities of Indian-Pakistani Origin in Eastern Africa edited by Adam, Michel pg 104,118)

The Archaeology of the Jesuit Missions in Ethiopia (1557–1632) by Víctor Manuel Fernández pg 30-34

The Indian Door of Täfäri Mäkonnen's House at Harar by Richard Pankhurst pg 381,

New Aspects of India's Influence on the Art and culture of ethiopia pg 11-12

The Role of Indian Craftsmen in Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Ethiopian Palace, Church and Other Building Richard Pankhurst pg 11-20), The Indian Door of Täfäri Mäkonnen's House at Harar by Richard Pankhurst pg 389-391

The Nineteenth-century Carved Wooden Doors of the East-African Coast by Judith Aldrick

The visual resonances of a Harari Qur’ān by Sana Mirza

Memorials of Sovereignty: Funerary Architecture of the Siddis of Janjira at Khokri (Maharashtra) by Pushkar Sohoni

The African Dispersal in the Deccan by Shanti Sadiq Ali pg 153)

An African Indian Community in Hyderabad by Ababu Minda Yimene pg 191-103)

see “Rise of the Coastal Consumer: Coast-Side Drivers of East Africa’s Cotton Cloth Imports, 1830–1900” in Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick

Eastern Africa and the Indian Ocean to 1800 by Randall L. Pouwels pg 412-413)

I love your work. I would only suggest you keep it shorter — perhaps, serialise it — bear in mind that Jack and Zuckerberg have ruined our attention spans.