Centralizing power in an African pastoral society: The Ajuran Empire of Somalia (16th-17th century)

A political watershed in the southern Horn of Africa.

The southern Horn of Africa is home to some of the world's oldest pastoral societies and studies of these societies have generated a wealth of literature about their expressions of power. The Historiography of Somalia is often set against the background of such studies as well as the modern region’s politics, resulting in a cocktail of theories which often presume that the contemporary proclivity towards decentralization was a historical constant.

In the 16th century, most of Southern Somalia was united under the Ajuran state, an extensive polity whose rulers skillfully combined multiple forms of legitimacy that were current in the region and created a network of alliances which supported an elaborate administrative system above the labyrinthine kinship groups.

This article sketches the History of the Ajuran empire from the emergence of early state systems in the southern Somalia during the late 1st millennium, to Ajuran's decline in the 17th century.

Map of Southern Somalia showing the approximate extent of Ajuran in the 16th century.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The early southern Horn of Africa:

In the era preceding the emergence of Ajuran polity in southern Somalia, the coastal region and its immediate hinterland in the Shebelle river basin was primarily settled by a diverse group of agro-pastoral people who spoke languages belonging to the cushitic-language subgoup (mostly the Somali1 language) and the bantu-language subgroup (mostly the Sabaki languages), in a region which constituted the northern-most reaches of the Shungwaya proto-state, which in the late 1st millennium, extended from the mouth of the Shebelle river, then south to the Tana river in Kenya.2

Map showing shungwaya and the city-states that succeeded it

In this varied social and physical environment, defensive alliances, patron-client ties, cultural exchanges and intermarriages were used to mediate the shared economic interests of the sedentary agriculturalists and the pastoralist groups, the former of whom primarily constituted the Sabaki language groups while the latter primarily constituted the Somali-speakers (although both groups had semi-sedentary sections).3

These client relations often involved one group establishing a level of political hegemony over another. In the Shebelle basin, these forms of political structures were primarily headed by the pastoralists (such as the Somali, and later the Oromo) who were numerically stronger, while along the coast from southern Somalia to central Tanzania, the sedentary agriculturalists (such as the Swahili, Comorians and Majikenda —of the Sabaki language groups) were numerically stronger, and thus predominant in the East African coast’s political structures.4

Its because of this dynamic that while the early history and establishment of southern Somalia’s coastal settlements of Brava5, Mogadishu6, Merka7, Kismayu8, are associated with the Swahili speakers (of the Chimini and Bajuni dialects), who are still present in the cities as autochthonous groups9, The political power in these cities quickly came to include Somali-speaking clan groups, and the cities were sustained primarily through the initiative of the pastoral groups, who'd later establish other cities along the central coast of Somalia.10

As such, by the 13th century, we're given one of the earliest explicit mentions of a southern Somali-speaking clan group in an external source written by the Arab writers; Yakut (d. 1229) and Ibn Sa'id (d. 1274), both of whom mentioned the Hawiye clan family along the southern coast of Somalia, and considered the city of Merca as the Hawiye’s capital11, And by 1331, Mogadishu was governed by a sheikh of Somali-speaking extract.12

Merca in the early 20th century.

Political identity among Somali-speakers rested on membership in a discrete kinship group based on descent often referred to as "clan-families", which are comprised of vast confederations (subdivided into clans) whose members claim descent from a common ancestor13. Focusing on the predominantly pastoral clans among the Somali speakers14, leadership was often fluid and authority was based on a prominent individual's successful performance of power rather than from inherited right. Principles of; clan solidarity, religious/ritual power (which was inheritable), strategic political alliance through intermarriage and the control of natural resources, were the major forms of political legitmation.15

Genealogical relationships among Somali clan-families and clans, those mentioned in this article are highlighted (chart taken from Cassanelli)

The Ajuran empire.

Around the 16th century, a section of clans led by the Gareen lineage (within the Hawiye clan family), established the state of Ajuran (named after their own clan). The Gareen’s legitimacy came from its possession of religious power (baraka) and a sound genealogical pedigree, it drew its military strength predominantly from the pastoral Hawiye clans and supplemented it with the ideology of an expanding Islam to establish a series of administrative centers in and around the strategic well complexes that formed central nodes within irrigated riverbanks of southern Somalia.16

The Gareen rulers set up an elaborate administrative system which oversaw the collection of tribute from cultivators , herdsmen, and traders and undertook an extensive program of construction of fortifications and wells. They ruled according to a theocratic (Islamic) model and most accounts refer to the Ajuran leaders as imams, and refer to administrators of the Ajuran government as emirs, wazir, and naa'ibs.17

Central power was exercised through an elaborate alliance system that was constructed above the labyrinth of subordinate Hawiye clans, which enabled the Ajuran imams to control an extensive territory that extended from the coastal town of Mareeg, down to the mouth of the Jubba river, and northwards into Qallafo near the Ethiopia-Somalia border.18

In the Shebelle basin interior there were interior trading towns such as Afgooye and Qallafo, where an economic exchange primarily based on pastoral and agricultural products took place between the herders and the cultivators. This exchange depended on the mutual relationships between the various clans and ethnic groups. Herders obtained farm products in exchange for livestock, which were then sent to Mogadishu and Merca, where the main markets were located , for consumption by the townsfolk and for export.19

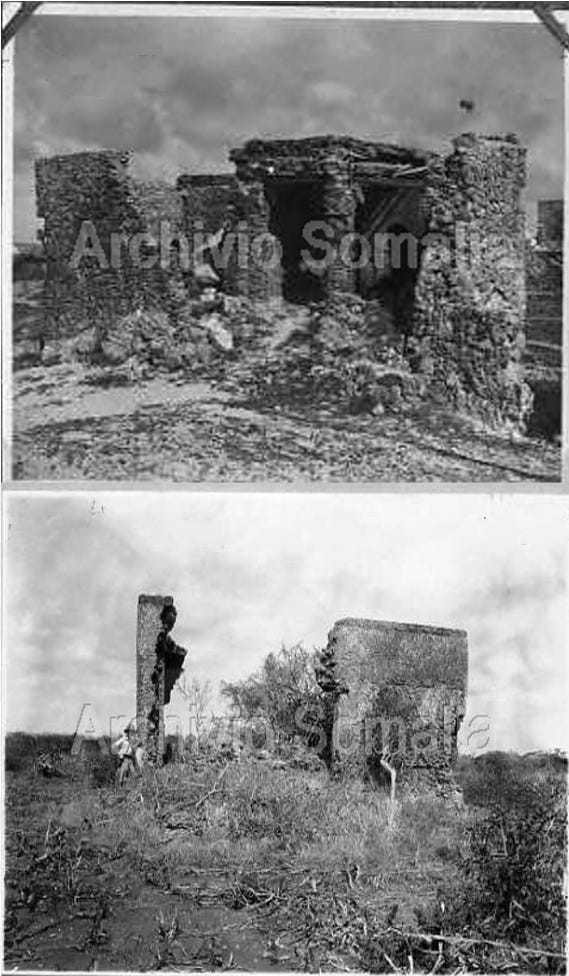

Military expeditions were also undertaken by the Ajuran rulers to expand their control into the interior as well as in response to incursions arising from a counter-expansion by a sub-groups of other Somali-speaking and Oromo-speaking groups in the region.20 In connection with the establishment of interior trading towns and military expansion, The Ajuran period witnessed considerable construction in stone deep in the Somali hinterland where many ruins have been discovered attributed to the Ajuran era (many of these ruins are now overgrown after centuries of abandon and remain undated).21

Remains of ancient buildings in the interior of southern Somalia, (photos from the early 20th century at Somali Studies Center -Somalia Archive)

Sustaining a pastoral aristocracy:

Prior to the Ajuran ascendance, the occupation of strategic well sites and thus grazing areas had enabled disparate Hawiye clans to establish a level of political hegemony over the populations of the Shebelle basin. This control of key pastoral resources provided the economic foundations for the extensive Ajuran polity whose political structure was in its origin a pastoral aristocracy.22

Ajuran’s Gareen rulers were closely associated with the Madinle (also spelt; Madale/Madanle ) either as allies or as directly related to the ruling elite. The Madinle are a semi-legendary group of well-diggers in Somali traditions who were claimed to possess the uncanny ability to identify aquifers for well construction23; a tradition that points to their role —along with the Ajuran— in monopolizing the region’s pastoral resources.

Many of the deep, stone-lined wells and elaborate systems of dikes and dams which irrigated the Lower Shebelle region, as well as ruined settlements in the region are traditionally dated to the Ajuran era.24 Although not all of the construction works would have been commissioned by the Ajuran rulers themselves.25

a traditional stone well in Somalia, early 20th century photo.

On Ajuran’s coast-to-hinterland interface: Mogadishu in the 16th century.

Alliances between the Ajuran rulers and the ruling dynasties of Mogadishu, Merca and Brava, enhanced the former’s power by providing an outlet for surplus grain and livestock which were exchanged the luxury goods that constituted the iconography of Ajuran's ostentatious royal courts26. Ajuran rulers were primarily concerned with domestic developments than with international politics, but were nevertheless intimately involved with coastal trade.27

While the coastal cities were not governed wholly by Ajuran officials; as their authority was typically exercised by councils of elders representing the leading mercantile, religious, and property-owning families, these cities were part of the Ajuran-controlled regional exchange system, and their social histories invariably reflected the vicissitudes of the hinterland.28

The Ajuran’s position in the Shebelle basin put them in the position of the middleman, by controlling the interior trade routes and meeting points, the state was able to yield considerable amounts of agricultural and pastoral wealth such that Mogadishu —then under its local Muzaffar dynasty in the 16th and 17th century— was essentially transformed into an outpost of the Ajuran.29

The existence of an agricultural surplus in the Ajuran controlled hinterland and extensive trade with the coastal cities is confirmed by a 16th-century Portuguese account which mentions interior products such as grain, wax and ivory as the primary exports of Mogadishu.30 The prosperity of Mogadishu during the Ajuran era with its maritime trade to southern India, which flourished despite its repeated sacking by the Portuguese, doubtlessly rested on its economic relationship with the Ajuran.31

Mogadishu beachfront in 1927.

Collapse of Ajuran.

Early in the 17th century, the Ajuran state entered a period of decline as it faced various internal and external challenges to its hegemony. The main impetus of this decline came from continued expansion of more Hawiye clans into the Shebelle basin which challenged the system of alliances established by the Ajuran rulers and thus undermined the foundation of their authority. 32

Within the Ajuran's alliance system, the Gareen lineage was eclipsed by the Gurqaate confederation, which led to the disintegration of Ajuran into various states with different clans carving up parts of the empire. These include the Abgal who controlled the Mogadishu hinterland, the Silcis who controlled Afgooye, and the El-Amir who controlled Merca (the latter two would be supplanted by other clans by the 18th century).33

Chronicles from Mogadishu briefly mention the appearance of a Hawiye clan from the city’s hinterland during the 17th century and the replacement of the Muzzafar rulers with a new line of imams from the Abgal clan (their use of the ‘imam’ title reflecting their retention of Ajuran’s administrative legacy).34 This occurred around 1624, and the new rulers resided in the Shangani quarter of Mogadishu, but their power base remained among the people in the interior.35

Southern Somalia thus sustained the established economic exchanges that would later be significantly expanded by the Ajuran’s successor states such as the Geledi kingdom in the 19th century.36

Conclusion: the legacy of Ajuran.

The Ajuran era in Somali history shows that despite the widely held notion that power in Eastern-African pastoral societies was widely dispersed among segmented groups, the centralization of power by one group was not uncommonly achieved and sustained over a large territory that was socially and ecologically diverse.

A convergence of political circumstances in the 16th century enabled the emergence of what was one of eastern Africa's largest states, whose political structure was not a break with the pastoral Somali system of clan alliances and patron-client links, but was instead an extension and innovation of them. Ajuran's unique combination of traditional and Islamic administrative devices was employed by its successors to establish similar states.

The Ajuran era, which antecedes the formal integration of the Eastern-African coast and mainland in the 19th century, was a watershed moment in the region’s political history.

NSIBIDI is one of Africa’s oldest indigenous writing systems, read about its history on our Patreon

Support African History on Paypal

(‘Somali’ in this article will be used to refer to the speakers of the Somali language rather than as a reference to the modern national identity which currently comprises many who speak other languages and excludes Somali speakers outside Somalia)

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 10-11)

The Benaadir Past: Essays in Southern Somali History by Lee V. Cassanelli pg 7-11

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 13-15)

The Swahili: Reconstructing the History and Language of an African Society by Derek Nurse pg 54-59)

Medieval Mogadishu by N. Chittick pg 48,50

Swahili and Sabaki: A Linguistic History By Derek Nurse pg 492

Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture & the Shungwaya Phenomenon By James De Vere Allen pg 91-158

Northeast African Studies, by African Studies Center, Michigan State University 1995 pg 23)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 74-75)

The Cambridge History of Africa. Volume 3, From c.1050 to c.1600 pg 137)

Medieval Mogadishu by N. Chittick pg 50)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 17

Luling makes the case for a distinction in the concepts of power between the pastoral-nomadic clans and the agro-pastoral clans on pgs 78-81 of '“Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years”

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 86)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 104)

Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture & the Shungwaya Phenomenon By James De Vere Allen pg 157, The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli 98)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli 102-103, Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture & the Shungwaya Phenomenon By James De Vere Allen pg 156

The Origins and Development of Mogadishu AD 1000 to 1850 by Ahmed Dualeh Jama pg 89)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 113)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 96

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 100-101)

Identities on the Move: Clanship and Pastoralism in Northern Kenya By Günther Schlee pg 94-96, 226-227

Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture & the Shungwaya Phenomenon By James De Vere Allen pg 156, The Benaadir Past By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 28)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 96)

Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture & the Shungwaya Phenomenon By James De Vere Allen pg 157

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 104)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 74)

The Origins and Development of Mogadishu AD 1000 to 1850 by Ahmed Dualeh Jama pg 89)

The Benaadir Past By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 27-8)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 113)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 107)

The Shaping of Somali Society By Lee V. Cassanelli pg 94-108)

The Origins and Development of Mogadishu AD 1000 to 1850 by Ahmed Dualeh Jama pg 91)

Medieval Mogadishu by N. Chittick pg 53 )

Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years by Virginia Luling