Constructing a global Monument in Africa: the Zagwe Kingdom and the Rock-cut churches of Lalibela -Ethiopia (12th-13th century)

Africa's New Jerusalem?

The colossal churches of Lalibela are some of Africa's most iconic architectural structures from the medieval era. Carved entirely out of volcanic rock, extending over an area of 62 acres and sinking to a depth of 4 stories, the 11 churches make up one of the most frequented pilgrimage sites on the continent, a visible legacy of the Zagwe kingdom.

The history of the Zagwe kingdom, which was mostly written by their successors, is shrouded in the obscure nature of their overthrow. The Zagwe sovereigns were characterized by their successors as a usurper dynasty; illegitimate heirs of the ancient Aksumite empire, and outside the political lineage within which power was supposed to be transmitted. The Zagwe sovereigns were nevertheless elevated to sainthood long after their demise, and are associated with grandiose legends especially relating to the construction of the Lalibela Churches.

This article explorers the history of the Zagwe kingdom and the circumstances in which one of the world's most renowned works of rock-cut architecture were created.

Map of the northern Horn of Africa during the early 2nd millennium showing the Zagwe kingdom and surrounding polities

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The northern horn of Africa prior to the ascendance of the Zagwe kingdom.

After the fall of the Aksumite empire in the 7th century AD, the succeeding rump states of the region ruled by Christian elites from their distinct geographical bases were engaged in a protracted contest of power and legitimacy, and the region was undergoing an era of deep political upheaval which is partially evidenced by the absence of a single, sufficiently strong central authority between them.1

In the northern and western regions that were part of the Aksumite heartlands, we're introduced to the enigmatic figure of non-Christian Queen Gudit, who ruled the region during the 10th century and may have been associated with the powerful kingdom of Damot. According to internal and external accounts about her reign (the former from an anonymous Aksumite king’s appeal to the Nubian King George II <d. 920>2, and the latter from Ibn Ḥawḳal <d. 988>), Gudit is said to have deposed the last Aksumite king and burned the kingdom’s churches, representing the decline of the Aksum’s political and ecclesiastical institutions. 3

Her reign's exceptional length and the extent of the social-political transformations which the societies of the northern horn experienced, underline the strength of the region’s new monarchs (of non-Abrahamic religions) who managed to confine the Christian states (and emerging Muslim states) for a time, to the frontier of their kingdoms.4

To the east of the former Aksumite heartlands were the emerging Muslim states and trading towns such as Kwiha and the red-sea island of Dahlak where mosques were constructed between the 10th and 11th centuries, and attest to the expansion of the Muslim communities in the region.5

In the southern reaches of the Christian controlled regions, a powerful confederation of non-Abrahamic (ie: “pagan”) states emerged called the “shay culture”. The Shay culture’s extensive trade with the red-sea region and their construction of monumental funerary architecture, were markers of an emerging power. Their flourishing during the era of Queen Gudit and the Damot kingdom, represented a wider movement in which the northern horn of Africa was dominated by states ruled by non-Abrahamic elites.6

The tumulus of Tätär Gur, a passage grave built for an elite of the Shay culture during the mid-10th century.7

The political crises between the weakening Christian states in contrast with the growing power of the non-Abrahamic states, precipitated the emergence of a Christian elite called the Zāgwē dynasty, which was eventually was able to gather enough political power to defeat the successors of Queen Gudit and their probable allies, and establish a Christian kingdom that was sufficiently strong in the region, and able to receive a metropolitan from the Alexandrian patriarchate; successfully restoring both political and ecclesiastic institutions.8

The Zagwe sovereigns, a short chronology

The first attested Zagwe monarch was king Tantāwedem who reigned in the late 11th century to early 12th century9. His reign is documented by a number of contemporary internal sources that include a rich endowment of land to the church of Ura Masqal (now in Eritrea), which possesses a land grant dated to the 12th year of his reign, and that introduces the Zagwe king’s three names in Aksumite style; his baptismal name Tantāwedem, his regnal name Salomon, and his surname, Gabra Madòen.10

In his donation, King Ṭänṭäwǝdǝm mentions a Muslim state from the region of Ṣǝraʿ (now in eastern Tigray), which he claims to have fought and defeated. He also lists several offices that provide a glimpse of the Zagwe’s territorial administration over a fairly large region which extended upto the red-sea coast.11

the church of Ura Masqal, founded by king Tantāwedem in the 12th century.

The successors of Tantawedem were King Harbāy and Anbasā Wedem who reigned in the 12th century. Documentary evidence for both monarch's reigns is relatively scant and is derived from internal records that mention as contemporary with the metropolitan Mikā’ēl I who is known to have served in the years between the office of the patriarch Macarius (1103-1131) and that of John V (1146-1167).12

During the mid-12th century, a delegation from the Zagwe kingdom was sent to Fatimid Egypt during this time with letters and presents to the Fatimid Calip al-Adid (d. 1171) but was received by his successor Caliph Salah al-Din in 1173, although the purpose for the delegation is unclear. 13

These two kings were succeeded by Lālibalā , whose reign in the late 12th/early 13th century is better documented. According to two land grants preserved in the Gospels of Dabra Libānos church, King Lālibalā was already reigning in the year 1204 and was still in power in the year 1225 when he made a donation to the church of Beta Mehdane Alam. Other internal manuscripts written long after his reign push his ascendance back to the year 1185 and state that he completed his rock-hewn churches in 120814.

Lālibalā is credited a number of ecclesiastical and political innovations that are recounted in written accounts on his reign (both external and internal) as well as in local oral traditions.

The 13th century Egyptian writer Abu al-Makarim mentions that the Zagwe king claimed descent from the line of Moses and Aaron (thus marking the earliest evidence of the use of ancient Israelite associations in Ethiopian dynastic legitimacy)15. He also mentions the presence of altars and "tablets made of stone", the presence of these altars is confirmed by the inscribed altars dated to Lālibalā's reign that were dedicated by the King in several rock-hewn churches.16

In the years 1200 and 1210, Lālibalā sent envoys and gifts to Sultan al-’Adil the ruler of Egypt and Syria (and the brother to Saladin, who also controlled Jerusalem). These gifts may have been connected with securing the safe passage of Christian pilgrims from Zagwe domains,17 because in 1189, Saladin had given a number of sites in Jerusalem to the Ethiopians residing there.18

The successors of Lālibalā were Na’ākweto La’āb and Yetbārak, both of whose reigns are also documented in later texts. The former ruled until the year 1250 and is presented as the nephew of King Lālibalā and son of King Harbāy, while the latter ruled upto the year 1270, he also appears in external texts as the last Zagwe King and is known to be the son of Lālibalā.19

In 1270, a southern prince named Yǝkunno Amlak seized the Zagwe throne under rather obscure circumstances and established a new dynasty often called “Solomonic”, -a term which is based on the legitimating myth of origin used by Amlak’s successors. The “Solomonic” monarchs who ruled medieval Ethiopia from 1270-1974, traced the descent of the their dynasty to the biblical King Solomon in the 10th century BC and through the Aksumite royals, they therefore dismissed the Zagwe rulers as usurpers, positing a “restoration” of an ancient, unbroken royal lineage that had been “illegitimately” occupied by the Zagwe.20

Rock-cut architecture and the churches of Lalibela.

Early Rock-hewn structures in the Northern Horn of Africa from the Aksumite era to the eve of the Zagwe’s ascendance.

The architectural tradition of creating rock-cut structures is an ancient one in the northern horn of Africa. The oldest of such structures date back to the icon rock-cut Aksumite ‘tomb of the brick arches’ dated to the 4th century during the pre-Christian era, and the 6th century funerary rock-cut churches and chapels that were set ontop of rock-cut tombs of Christian monarchs near the town of Degum (modern eastern Tigray).21

The iconic 4th century “tomb of the brick arches” in Aksum carved out of rock, its walls are lined with stone and bricks with arches separating its chambers.

Rock-hewn churches ontop of similarly constructed tombs increased in elaboration during the post-Aksumite era, with the construction of the church of Beraqit, and the cross-in-square churches of Abraha-wa-Atsbaha, Tcherqos Wukro, and Mika’el Amba that were carved during the 8th-10th century. By the 12th and 13th century, lone-standing rock-hewn churches that served solely as monastic institutions (without funerary associations) were constructed, these include the Maryam wurko and Debra Tsion churches. All of these rock-cut churches retain classical Aksumite architectural features and spatial design.22

The rock cut churches of Mika’el Amba and Tcherqos Wukro in eastern Tigray, created in the 8th-10th century.

The Lalibela rock-cut church complex.

While ecclesiastical traditions unequivocally attribute all of the Lalibela churches to king Lālibalā —whose name the place now bears—, this reflects the processes through which the Zagwe king was elevated to sainthood in the 15th-17th century rather than the exact circumstances of their construction in the early 2nd millennium.23

The Lalibela complex comprises of twelve rock-hewn structures (11 churches and one tomb) divided in three clusters of the "eastern", "northern" and western complex, that were carved out of soft volcanic rock over four major phases which saw the transformation of what were initially defensive pre-existing structures of into churches.24

Map of the Lalibela complex.25

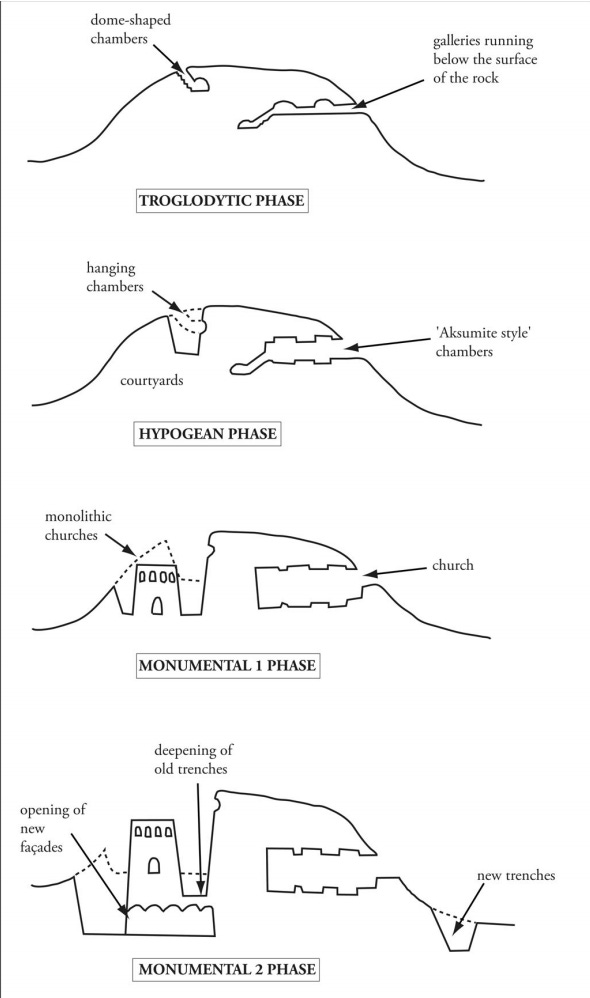

In their early (Troglodytic) phase of construction, the oldest structures consisted of small tunnels and flights of stairs cut into the rock that lead into domed chambers in the interior. During the second (Hypogean) phase, the rock-hewn structures consisted of extensive hypostyle chambers, galleries, heightened ceilings, ornamenting entrances with Aksumite-style pillars and doorways leading to open-air courtyards, and subterranean rooms cut.26

They were surrounded by defensive perimeter wall system built in the mid 10th to 12th century, that was cut through during the last phases of the transformation of the buildings into churches and buried under debris.27

phases of Lalibela rock-cutting process.28

That the older structures were carved by a pre-Christian population is evidenced by the figures carved on the walls of the rock-cut church of Washa Mika’el (located about 50km south-east of Lalibela) that include animals like humpback cattle, birds, giraffes, elephants and mythical creatures as well as Human figures with male sexual attributes. Christian murals were later added in the 13th century but the pre-Christian carvings were retained, representing a technical and religious syncretism that points to the pre-Christian population adopting Christianity rather than displacement by a foreign Christian population.29

A similar cultural transformation is noted among the other non-Abrahamic societies of the north-central region, most notably the medieval “shay culture” whose elaborate tumulus burials were discontinued during and after the 13-14th century.30

Pre-christian relief sculptures on the walls of the Washa Mika’el church, and Christian paintings (added later)

The final cutting phases of the Lalibela churches in the 13th century (Monumental 1 and 2 phases). This phase represented a departure in terms of the morphology of the site's functions, but a continuity in terms of the construction technology. Lalibela's transformation into a fully Christian religious complex represents a new architectural program that resulted in the complete concealment of previous pre-Christian defensive or civilian features.

Remnants of the rock-cutting sequence of Beta Gabriel-Rufael, showing the original courtyard and level (a), that was extended and lowered in (b) and further lowered in (c)31

The major transformations during this phase were the creation of new churches and the complete transformation of all structures into Christian monuments. This entailed the lowering of the structure's outside levels for hydrological, aesthetic and functional purposes, the enlargement of the open-air courtyards, and inclusion of elaborate designs of the church’s interior and façade.32

the basilica-like façade of the Beta Madhane Alam church

It's unclear whether these final phases all took place under king Lālibalā in the early 13th century as suggested by some scholars33, or the process continued under later rulers both Zagwe and Solomonic, as evidenced by the rock-cut church of Dabra Seyon attributed to Na’ākweto La’āb34, the murals of the nearby Washa Mika’el church dated to 127035, and the nearby rock-cut church of Yemrehanna Krestos that dates to the 15th century.36

Based on architectural styles and liturgical changes, some scholars propose the following chronology in completion of construction; the churches of Beta Danagel, Beta Marqorewos, Beta Gabreal-Rufael, Beta Marsqal and Beta Lehem (as well as Washa Mika’el) were carved from much older structures that were later transformed into churches in the 13th century, while the monolithic rock-cut churches of Beta Maryam, Beta Madhane Alam, Beta Libanos and Beta Amanuel were likely created during the 13th century.37

the churches of Beta Marqorewos and Beta Amanuel

the churches of Beta Maryam and Beta Libanos

The churches of Beta Dabra Sina-Golgota, Adam's tomb and Beta Giyorgis (and the distant churches of Yemrehanna Krestos and Gannata Maryam) were likely completed during the 14th and 15th century.38

The churches of Beta Dabra Sina-Golgota and Beta Giyorgis

the church of Yemrehanna Krestos

Lalibela as a “New Jerusalem”.

The extensive construction program under the Zagwe rulers -which stands as one of the most ambitious of its kind on the African continent at the time- has led to a flurry of theories some of which tend towards the exotic.

The symbolic representation of the Holy Sepulcher in the church of Golgota, the topographic names of Mount Tabor, the Mount of Olives, the Jordan River, (with its monolithic cross symbolizing the place of baptism of Christ) that are derived from famous landmarks in Jerusalem, all seemed to support a grandiose tradition —magnified by later scholars— that Lalibela sought to create a new Jerusalem after the “old” Jerusalem was captured by the Muslim forces of Saladin.39

sculpture of saint George in the church of Beta Dabra Sina-Golgota

However, the transposition of Jerusalem outside of Palestine by medieval Christian societies, was not specific to the Christian kingdoms of the northern horn of Africa, and is unlikely to have been linked to the difficulty of travelling to Jersualem’s Holy Places for pilgrimage. The transposition of Jerusalem is instead often a tied to internal political contexts and experiences of pilgrims, both of which inspire the replication on local grounds of a “small” Jerusalem as symbol of the new covenant and their ruling elite’s divine election. The churches of Lālibalā were therefore not conceived as a “new” Jerusalem replacing the Jerusalem of the Holy Land, but were instead seen as a "small" Jerusalem, and a symbol of the divine election of the Zagwe monarchs during and after their reign.40

Around the 15th century, the churches of Lalibela and the adjacent churches such as Yemreḥanna Krestos became very popular places of pilgrimage for Christian faithfuls in the region, who came to commemorate the Zāgwe sovereigns associated with their construction and developed a cult in their honour.41

This elevation of the Zagwe sovereign’s image from political figures to Saints from the 15th to the 17th century, was tied to the emergence of the medieval province of Lāstā, as a region that was semi-independent from the Solomonic empire.42 Its also during this time that the hagiographies of the Zagwe kings were written, but their circular constructions, and the nature of their composition centuries after the Zagwe’s demise, make them relatively unreliable historiographical sources unlike similar Ethiopian hagiographies.43

Folio from Gädlä Lālibalā ("The Acts of Lālibalā”) A 15th century hagiographic account of the life of King Lālibalā, depicting the King constructing the famous churches.

Lalibela as a capital of the Zagwe and the “southern shift” of the Christian kingdom

Lalibela has often been considered the capital of the Zagwe rulers party due to its monumental architecture, and external writers’ identification of Adefa/Roha (a site near the Lalibela churches) as the residence of the King, or “city of the king”.44

But this exogenous interpretation of the functioning of the Zagwe State at this period has found little archeological evidence to support it, the area around the churches had few secular structures and non-elite residences that are common in royal capitals, and lacked significant material culture to indicate substantial occupation. Lalibela more likely served as a major religious center of the Zagwe kingdom rather than its fixed royal residence.45

A closer examination of the donations made by the Zagwe rulers also reveals that their activities were concentrated in the northern provinces historically constituting the core of the old Aksumite state , showing that the center of the kingdom wasn't moved south (to Lalibela), but rather expanded into and across the region, where the churches were later constructed.46

The notion of a southern shift of the Aksumite state that was partly popularized by the legitimizing works of the “Solomonic” era, is difficult to sustain as the Zagwe kings used Ge’ez in the administration of the kingdom, concentrated their power in the Aksumite heartlands, utilized (and arguably initiated) the ideological linkages to ancient Israelite kingship, and by establishing a powerful state, oversaw a true revival (or restoration) of Christian kingdom in the northern Horn of Africa. The Zagwe were in reality, much closer to the Aksumite kings than to their successors, who evidently appropriated their ideology to suite their own ends.47

The colossal churches of Lalibela stand as a testament to the legacy of the Zagwe kingdom, a monumental accomplishment of global proportions deserving of its status as the semi-legendary ‘Jerusalem of Africa’.

Medieval Ethiopia has a rich history including legends about its ability to divert the flow of the Nile River, read more about it on our Patreon

Support African History on Paypal

THANKS FOR YOUR SUPPORT ON PATREON AND FOR THE DONATIONS. FOR ANY SUGGESTIONS AND RESEARCH CONTRIBUTIONS, PLEASE CONTACT MY GMAIL isaacsamuel64@gmail.com

La culture Shay d'Éthiopie (Xe-XIVe siècles) by François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar pg 23)

The Letter of an Ethiopian King to King George II of Nubia by B Hendrickx

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea by Samantha Kelly pg 36

La culture Shay d'Éthiopie (Xe-XIVe siècles) by François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar pg 29)

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea by Samantha Kelly pg 42

La culture Shay d'Éthiopie (Xe-XIVe siècles) by François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar pg 367-372

La culture Shay d'Éthiopie (Xe-XIVe siècles) by François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar pg 133

The Zāgwē dynasty (11-13th centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos by Marie-Laure Derat pg 162)

Les donations du roi Lālibalā by Marie-Laure Derat pg 26)

The Zāgwē dynasty (11-13th centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos by Marie-Laure Derat pg 162-163)

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea by Samantha Kelly pg 42-44

The Zāgwē dynasty (11-13th centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos by Marie-Laure Derat pg 164-165)

Church and State in Ethiopia by Taddesse Tamrat pg 57

The Zāgwē dynasty (11-13th centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos by Marie-Laure Derat pg 165-166)

The quest for the Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 51)

Les tombeaux des rois Zāgwē, Yemreḥanna Krestos et Lālibalā (XIIe-XVIe siècle), et leurs évolutions symboliques by Marie-Laure Derat pg 14-16)

The quest for the Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 184)

Church and State in Ethiopia by Taddesse Tamrat pg 58

The Zāgwē dynasty (11-13th centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos by Marie-Laure Derat pg 166)

The quest for the Ark of the Covenant by stuart Munro-Hay pg 84-87

Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn by D. W Phillipson pg 147

Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn by D. W Phillipson pg 147- 203-223)

Les tombeaux des rois Zāgwē, Yemreḥanna Krestos et Lālibalā (XIIe-XVIe siècle), et leurs évolutions symboliques by Marie-Laure Derat

The Lalibela Rock Hewn Site and its Landscape (Ethiopia) by C Bosc-Tiessé pg 144-146)

The Lalibela Rock Hewn Site and its Landscape (Ethiopia) by C Bosc-Tiessé pg 145

Rock-cut stratigraphy: sequencing the Lalibela churches by Francois-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar pg 1143)

The rock-cut churches of Lalibela and the cave church of Washa Mika’el by Marie-Laure Derat pg 470)

Rock-cut stratigraphy: sequencing the Lalibela churches by Francois-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar pg 1147

The rock-cut churches of Lalibela and the cave church of Washa Mika’el by Marie-Laure Derat 481-483)

The Shay Culture of Ethiopia (Tenth to Fourteenth Century AD): Pagans in the Time of Christians and Muslims by François-Xavier Fauvelle

Rock-cut stratigraphy: sequencing the Lalibela churches by Francois-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar pg 1141

The rock-cut churches of Lalibela and the cave church of Washa Mika’el by Marie-Laure Derat 1146-1147)

Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn by D. W Phillipson pg 235-237)

The quest for the Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 82

The rock-cut churches of Lalibela and the cave church of Washa Mika’el by Marie-Laure pg 1147)

Rock-cut stratigraphy: sequencing the Lalibela churches by Francois-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar pg 1148)

Churches Built in the Caves of Lasta (WÃllo Province, Ethiopia): A Chronology, by Michael Gervers pg 31-32)

Churches Built in the Caves of Lasta (WÃllo Province, Ethiopia): A Chronology, by Michael Gervers pg 36)

Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270-1527 by Taddesse Tamrat pg 59

Les tombeaux des rois Zāgwē, Yemreḥanna Krestos et Lālibalā (XIIe-XVIe siècle), et leurs évolutions symboliques by Marie-Laure Derat pg 11)

Les tombeaux des rois Zāgwē, Yemreḥanna Krestos et Lālibalā (XIIe-XVIe siècle), et leurs évolutions symboliques by Marie-Laure Derat pg 15-16)

The Zāgwē dynasty (11-13th centuries) and King Yemreḥanna Krestos by Marie-Laure Derat pg 190)

A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea by Samantha Kelly pg 32

Church and State in Ethiopia by Taddesse Tamrat pg 59

The Lalibela Rock Hewn Site and its Landscape (Ethiopia) by C Bosc-Tiessé pg 162)

Les donations du roi Lālibalā by Marie-Laure Derat pg 34-37)

discussed at length in “The quest for the Ark of the Covenant’ by Stuart Munro-Hay