Constructing Peace in a pre-colonial African state: Diplomacy and the ceremony of dialogue in Asante

"Never appeal to the sword while a path lay open for negotiation"

Despite its well deserved reputation as a major west African military power, the Asante employed the practice of diplomacy as a ubiquitous tool in its art of statecraft. Treaties were negotiated, the frontiers of trade, authority and territory were delimited, disputes were settled, and potential crises were averted .

As a result of the diplomatic maneuverings of astute Asante statespersons working through their commissioned ambassadors, embassies were dispatched to various west African and European capitals, and couriers were sent across the Asante provinces to advance Asante’s interests globally and regionally.

This article explorers the history of Asante’s diplomatic systems and the ceremonies of dialogue that mediated the kingdom’s international relations.

Asante at its greatest extent in the early 19th century

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Regional and international Asante; the need for diplomacy.

By the late 18th and early 19th century, the Asante state had developed an elaborate administrative system. The increasing volume of governmental needs led to the establishment of a complex bureaucracy with systems for legislative, judicial, financial administration and foreign relations. Its within this context that a class of professional diplomats emerged, who served as specialists in the conduct of foreign relations.1

The establishment of a professional class of envoys in Asante was partly in response to the rapidly changing political landscape of West Africa and the Gold coast region (the coast of modern Ghana), the latter of which had been recently subsumed by Asante's expansionism, while the former was closely integrated within Asante’s trade networks. In the Gold coast region, the formerly (politically) subordinate European traders were increasingly extending their commercial and political hegemony at the expense of the Asante's interests, and sought to bypass the Asante's control of the commodities trade from the interior (Asante's north).2

The changing mode of engagement with the coast-based European traders, who were after 1807 mostly interested in the commodities trade; especially in items whose production was largely controlled by the Asante, resulted in a more direct level of correspondence with the Asante court3.

From the late 18th century, Asante received and sent diplomats to its African neighbors of Dahomey and Wasulu, and within just 5 years between 1816-1820, King Osei Bonsu (r. 1804-1824) received 9 European diplomats representing different countries and interests, a gesture which was reciprocated with Asante envoys travelling to the coast with the same frequency. The activity of these envoys steadily rose in the 1830s, and over the last half of the 19th century, as all regional and international parties became more politically entangled.4

Construction and performance of Asante’s diplomatic institution

Within the Asante bureaucratic system, the diplomatic class was often taken from a section of public servants called the nhenkwaa. Individual envoys were often selected based on their competence, diplomatic and communication skills, experience with the culture of their intended guests, as well as their position within the Asante political structure.5

Asante officials traveling abroad in diplomatic capacity were initially of two kinds; "career" ambassadors and couriers; the former of whom could negotiate with their hosts on their own authority as conferred to them by the King, while the latter —who attimes included foreign traders— could only relay information but couldn't negotiate in any capacity.6 As Owusu Ansa, one of the top Asante diplomats in 1881 clarified about the past conduct of a messenger in the latter’s negotiations with the British that; "no Ashanti taking the King's message would dare to add or to take from it,"7

Over the 19th century however, the distinction between the official envoys and messengers was blurred by the emergence of other titled officials such as the afenasoafo, who not only transmitted official messages but also came to assume more official but lesser diplomatic duties including negotiating the return of fugitives.8

Established procedures regulated the various spheres of diplomatic activity, from the swearing in ceremony of the official envoys —as observed by (British envoy to Asante) Thomas Bowdich in 1817 while witnessing the preparations for Asante’s diplomats to the Cape coast (a British-owned castle at the coast and base of a small colony)—, to the specification of individual envoy's powers and latitude in negotiation.

The envoys performed a variety of functions depending on their delegated capacities, including negotiating and ratifying peace agreements; issuing official protests, resolving foreign disputes, demanding fines, as well as extraditing Asante fugitives. Covertly, the diplomats also engaged in other activities including commercial duties, and espionage, depending on the security and foreign policy concerns of the central government.9

While in foreign territory, the diplomatic immunity and recognition of official Asante envoys was secured by having them carry the necessary credentials, wearing special clothing and equipping them with symbols of office.

Ambassadors of high rank were dressed in costly garments that constituted "public state wardrobe" as observed by Bowdich in 1817, provided by the King to the Ambassador to “enrich the splendor of his suite and attire as much as possible" that was kept especially for the purpose.10 The lower ranks in the Asante diplomatic retune carried badges of offices such as golden discs, Staffs of office, and gold-handled swords.11

Asante wooden staffs of office covered with gold leaf, late 19th-early 20th century (art institute Chicago, Houston museum of fine arts, Smithsonian)

Asante ceremonial sword and sword handle of a hand holding a serpent, dated 1845–1855, (British Museum, Houston Museum)

Asante gold badge, dated 1870-1895, Houston Museum of Fine Arts

The size of the envoy's retinue, which often included titled officials from various Asante provinces, served as an index of the importance of the ambassador as well as the importance of the intended subject of discussion. Every effort was made to impress the guests with the size of the embassies, in line with Asante ceremonial pomp that accustomed such diplomatic occasions.12

As such, the size of the train of ambassadors such as Owusu Dome in 1820 was said —with some exaggeration— to be as many as 12,000, and the size of Kwame Antwi’s embassy in 1874 numbered around 300 men. As (British envoy to Asante) Joseph Dupuis noted on Owusu's arrival at Cape coast; "the ambassador entered the place with a degree of military splendour unknown there since the conquest of Fante by the (Asante) King."13 The Asante always insisted that proper respect should be paid to their representatives abroad and were quick to punish slights, especially when the offenders were the their sphere of influence such as the Fante of the Gold coast.

While all Asante diplomatic procedures were initially conducted orally, the broadening reach of Asante's foreign affairs (with both the Europeans along the coast and the Muslim states of West Africa) led to the adoption of written forms of official diplomatic communication to record the proceedings of Asante's embassies, but mostly to supplement rather than displace the established oral system of official communication.14

By the second half of the 19th century, a sort of chancery was in place Kumase as an archive of the state’s volume of foreign correspondence, whose extent can be gleaned from the number of extant letters from Kumasi that were addressed to various foreign states15. The chancery's staff that were employed on an adhoc basis composed letters on behalf of the government, as well as translating and interpreting foreign letters and counseling the King on foreign policy issues as requested.16

A carder of learned officials were trained by the Asante to staff and supervise the chancery. These included the princes Owusu Nkwantabisa and Owusu Ansa, who were educated under British auspices at Cape Coast and in and their younger siblings; John Ansa and Albert Ansa were educated in England. They were assisted in their chancery tasks by the various foreign adhoc officials whose activities were closely supervised due to suspicions over their divided loyalties.17

Receiving Foreign Diplomats in Asante:

The foreign policy of the Asante state was decided by the king and his advisers (the Kumasi council), subject to a veto by the aristocracy in the general council.18 For this reason, no envoy was welcome in the capital until the king had to assemble the Kumasi council and be properly briefed. The procession of foreign envoys to Kumasi was defined by a distinct pattern of prescribed halts that were ostensibly concerned with giving both the visitors and the Asante court time to assemble, organize, and prepare themselves for the forthcoming encounter.19

Foreign envoys bound for the Asante capital from the coast were always stopped in the southern districts where they had to wait until the king was ready to receive them, the waiting period varying from a day to several weeks. An envoy who objected to this delay was warned by his assigned escort against proceeding to the capital without the approval of the King.20

Asante officials who violated the strict code of diplomatic conduct were subject to punishment. In 1816 when two senior army commanders negotiated with the people of Elmina without the king's knowledge and flagrantly disobeyed the orders of the metropolitan government, one of the generals was subsequently tried in public, convicted of treason, stripped of his offices and possessions.21

Following an elaborate reception ceremony in which the guest’s progress and reception proceeded in a highly orchestrated manner, the foreign envoys were allotted free accommodation in the city by the government official responsible (often the royal treasurer) who then provided them with all their necessities during the entire length of the stay.22 While the foreign envoys were in Kumasi, the afenasoafo officials mentioned earlier often served as the diplomatic channels of communication between the King and visiting envoys.23

The envoys were often given official audience in semi-public settings that mostly included the sections of the public, top officials of the state (ie members of the council) as well as the King, while more confidential matters were negotiated in private with the envoy appearing alone with the King and four senior council members. Treaties and agreements were proclaimed and made binding in the presence of those who were affected by them, while general policy statements were delivered to the public.24

The task of publicizing the results of new decrees and agreements resulting from diplomatic negotiations fell on the nseniefo (heralds) , who were the most important agents of communication in the nineteenth century.25

The Oath taking procedure involved various practices depending on the origin of the envoy, they included swearing on a the Bible for Europeans, the Koran for Muslims (and some Europeans) and taking a traditional drink in the presence of the court.26 According to the Asante principle, the envoys were under Asante law once they were within Asante territory and could thus only be allowed to depart upon receiving permission from the King. 27

The Ceremony of dialogue:

The pomp and ceremony of a foreign envoy's reception had several purposes and greatly depended on the expectations which the Asante government had of a foreign mission. The hosts carefully combined several forms of public displays intended to impress and intimidate their guests on the power and wealth of the Asante state, and communicate the significance (or insignificance) of the guests to the Asante public.28

The ceremony thus conferred royal recognition on the visitors and integrated them within the hierarchical structure of Asante society by allocating them a suitable place inside it.29 The invited guest, who lacked the power and splendor of their host, found themselves on equal footing to their host at the ceremonial event, and the order in which the visitors were introduced to the general assembly and the configuration of each chief’s retinue combined to reproduce a physical and spatial representation of Asante society’s basic composition and hierarchical structure.30

These grand ceremonies such as the one excellently depicted by Bowdich titled: "First Day of the Yam Custom", displayed the Asante's selective inter-cultural appropriations of conventions and symbolism taken from traditional Akan iconography, west African-Islamic iconography and European iconography that represented an important diplomatic encounter.31

Detail of Asante king Osei Tutu Kwame surrounded by his courtiers, subjects, and European guests.

When the envoys were conducted to the king's presence, every effort was made by the Asante side to impress the new Arrivals with the magnificence of the Asante state. Most of the residents of the capital and surrounding towns were summoned to attend the proceedings. The king, provincial nobels, and officials were magnificently dressed and profusely decorated with gold ornaments. Musical instruments were sounded, muskets were fired, and the military captains ushered in the envoys.32

The success of such a carefully organized ceremony can be read from the accounts of several European envoys who were conducted to Kumasi in the early 19th century, as one Willem Huydecoper in 1816 writes;

"what a tumult greeted me there!, There are more than 50 thousand people in this place! His Majesty has summoned all the lesser kings from the surrounding countryside for today's assembly. Every one of them was splendidly adorned with gold, and each had more than 50 soldiers in his retinue. There were golden swords, flutes, horns, and I know not what else in profusion. When I saw all this, I felt very grateful for His Majesty's courtesy Towards me".33

A similar scene was witnessed by Dupuis also states in his journal that at this same spot in 1820, he was confronted with "The view was suddenly animated by assembled thousands in full costume, chiefs were distinguished from the commonalty by large floating umbrellas, fabricated from cloth of various hues. all the ostentatious trophies of Negro splendour were emblazoned to view"34

and by Bowdich in 1817; “The sun was reflected with a glare scarcely more supportable than the heat, from the massy gold ornaments, which glistened in every direction More than a hundred bands burst at once on our arrival with the peculiar airs of their several chiefs the horns flourished their defiances with the beating of innumerable drums and metal instruments, and then yielded for a while to the soft breathings of their long flutes, which were truly harmonious and a leasing instrument”35

Not every envoy received such a glorious welcome however, for when Jan Nieser sent envoys to Asante with the object of discrediting Huydecoper as representative of the Dutch, the king at first refused to see them, later reluctantly fixed a date for their entry into the capital, and then failed to accord them any ceremonial welcome. 36

As Huydecoper noted in his journal; "To the Ashantees, anyone who arrives without having honor done to him by the King is an object of scorn and is cursed by the common people"37 and the effect of the ceremonies and encounters with the court was best summarized by Dupuis “it naturally occurred to me that the impression was intended to paralyze the senses, by contributing to magnify the man of royalty”38

The results of Asante diplomacy: Relations with Asante’s African neighbors and Europeans.

Asante and Dahomey; from foes to allies

The simultaneous expansion of the Asante and Dahomey states in the mid 18th century had brought both states on a path of collision. As the relationship between the two states deteriorated Dahomey begun supporting rebels in Asante's eastern provinces, a threat that the Asante King Kusi Obodom (r. 1750-1764) responded to in kind with an invasion of Dahomey that ended in an inconclusive battle between the two forces in 1764, and resulted in significant causalities on the Asante side. Hoping to avert future conflicts, the ruler of the Oyo empire (Dahomey's suzerain) dispatched a mission to Kumasi in the same year to which Kusi's successor Osei Kwado reciprocated by sending a splendid embassy to Dahomey's capital Abomey that was warmly received. In 1777 and 1802 envoys from Abomey were received in Kumase as Dahomey strove to maintain cordial relations with Asante.39

When tensions between the two states flared up again in the mid 19th century that resulted in a second Asante-Dahomey war in the 1830s that resulted in a peace treaty between the two attained by both state's envoys, with a resumption in the sending of embassies between the two states. In 1845, an Asante embassy was present in Abomey with 40 retainers and stayed for five years. Other Asante embassies to Dahomey were sent in 1873 (prior to the British invasion), and in 1880, the latter of which was successful in receiving assistance from the Dahomey king Glele in restoring Asante authority to the east, after Glele had assessed the European threat to both him and Asante. 40

In October 1895, Asante King Prempeh I dispatched envoys accompanied by 300 officials to the Wasulu emperor Samory Ture bearing a gift of 100 oz of gold , in response to the latter's earlier embassy to Kumasi. Prempeh requested that Samory assist him to recover Asante's breakaway provinces in the west, the result of which was a decisive shift in Asante's authority in the region as rebellious provinces re-pledged their allegiance to Kumasi.41

The legacies of the Ansa family in Anglo-Asante diplomacy:

The careers of the ambassadors Owusu Ansa (senior) and his son John Ansa exemplify the preeminence of diplomacy in Asante's foreign relations. While Owusu had been educated and converted to Christianity under British auspices as part of negotiations between the Asante and the British following the first series of wars in the 1820s, he was turned into King Kwaku Dua's envoy upon his second return to Asante in lieu of his originally intended missionary objectives.

Owusu Ansa in 1872, Basel Mission archives

In one of his first tasks, Owusu successfully averted an attack in 1864 by the Asante forces against the coastal regions whose control was disputed by the British. Owusu was retained by Kwaku Dua's successor King kofi and In 1870, Owusu drafted a letter for the King protesting the Dutch handover of the Elmina fort to the British, and in 1871, led an embassy to exchange war prisoners with the British. In 1873, his role as an ambassador raised suspicion in the cloud of growing tensions between the British and Asante, resulting in a cape coast mob to burn his house, and the British tactically offered him 'vacation' in sierra Leone in preparation for their 1874 invasion.

He nevertheless believed he could prevent the impending Anglo-Asante war of 1874, writing to the cape coast governor that "if I were put in position to communicate authoritatively with the King of Ashantee as an envoy from the Queen, I might be able to terminate the present unhappy war on term honourable and advantageous to both sides".42

After the Asante loss in 1874, Owusu was retained by King Mensa Bonsu and was instrumental in the institutional reforms of the Asante state during a critical time when many of its provinces were breaking away He also successfully secured the supply of thousands of modern snider rifles in 1877-1878 to increase the army’s strength, and recruited foreign personnel to build up a new civil service.43

In 1889, Owusu’s son; John Ansa was appointed as an ambassador by the reformist King Prempeh and, along with his brother Albert Ansa, they influenced Asante's decision to reject British protectorate status in 1891 and expanded their father's diplomatic and commercial networks with independent French traders to supply modern firearms and foreign military trainers in 1893 and 1894 and reportedly made overtures to the French to counteract the British.44

As tensions grew between Asante and the Cape coast governors who were increasingly pushing the British to occupy Asante, John further influenced Asante's rejection of British protectorate status in 1893, writing that

"As my countrymen are desirous of continuing their independence, I beg here to strongly suggest to your excellency that it is essential that the British Government ought now to formally acknowledge Ashanti as an independent native empire, or in other words engagements entered into with her and the Ameer of Afghanistan by which annexation by any power is deemed impossible" After learning that the Cape coast governors were intent on war, Ansa advised Prempeh to dispatch an embassy to London which left successfully in 1895 due to Ansa’s contacts despite the Cape coast governor’s strong protests.45

While not fully received as an official embassy due to objections from the colonial office, Ansa successfully navigated Britain's legal system and hired solicitors to affirm his credentials as an official envoy that negotiated with full authority. But the colonial office was intent on frustrating their negotiations with the British government, and upon instigation by cape coast governor about the supposed alliance between Samory and Asante, as well as the looming threat of French competition, colonial secretary Chamberlain authorized the invasion of Asante. Ansa, who had assessed the strength of the invading force, hurried back to Kumasi ahead of the British expedition of 1896 and was instrumental in convincing Prempeh not to array his forces against what would have been a disastrous engagement, saving Kumasi a pillaging it had suffered in 1874 and preserving most of Asante’s state apparatus. Recognizing the role Ansa had played, the invading force fabricated charges against him (regarding his diplomatic credentials) but later dropped them.46

While 1896 may have closed the chapter on Asante's political autonomy, its diplomatic legacy would continue throughout the colonial and independent governments, as the former Asante core negotiated its way through successive regimes.

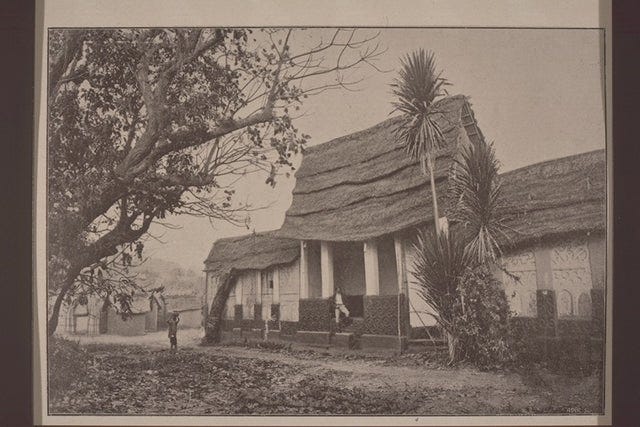

Kumasi 1896

Conclusion.

The Asante expertly used soft power and adopted cultural diplomacy within their official structures in order to direct foreign policy through organized channels of communication, symbolism, and ceremony. The Asante penchant for the art of diplomacy was remarked upon by many observers and is preserved in an famous Asante maxim;

"never appeal to the sword while a path lay open for negotiation"47

The Asante diplomatic institution was dynamic enough to adopt selective elements of foreign communicative processes while retaining its traditional form and distinctive features, enabling Asante to achieve its political objectives through a less costly and more favorable avenue than war —peace.

A PRE-COLOMBUS DISCOVERY OF AMERICA?

read about “Mansa Muhammad's journey across the Atlantic in the 14th century, and an exploration of West Africa's maritime culture from the 12th-19th century”

THANKS FOR YOUR SUPPORT ON PATREON AND FOR THE DONATIONS. FOR ANY SUGGESTIONS AND RESEARCH CONTRIBUTIONS, PLEASE CONTACT MY GMAIL isaacsamuel64@gmail.com

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg 488)

Wrapping and ratification: an early nineteenth century display of diplomacy Asante ‘Style’ by Fiona M. Sheales pg 50)

The Political Economy of the Interior Gold Coast by Jarvis L. Hargrove pg 143-144

“Sights/Sites of Spectacle: Anglo/Asante Appropriations, Diplomacy and Displays of Power 1816-1820” by Fiona Sheales pg 3

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg 489

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 93)

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg 497

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg pg 490

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg 495

Asante in the Nineteenth Century by Ivor Wilks pg 324)

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 94)

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg 497-498

Journal of a Residence in Ashantee by Joseph Dupuis pg xxviii)

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg 500-501)

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg 502)

for a critique of the exact nature and functions of this chancery’ see: “State and Society in Pre-colonial Asante By T. C. McCaskie” pg 332-333

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg 502)

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 86)

Sights/Sites of Spectacle: Anglo/Asante Appropriations, Diplomacy and Displays of Power 1816-1820” by Fiona Sheales pg 88

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 87)

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 87)

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 90)

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg 490

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 90)

Indigenous African Diplomacy: An Asante Case Study by Joseph K. Adjaye pg 490

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 91)

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 92)

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 10)

Wrapping and ratification: an early nineteenth century display of diplomacy Asante ‘Style by Fiona M. Sheales pg 52)

Sights/Sites of Spectacle: Anglo/Asante Appropriations, Diplomacy and Displays of Power 1816-1820” by Fiona Sheales pg 107

Wrapping and ratification: an early nineteenth century display of diplomacy Asante ‘Style by Fiona M. Sheales pg 48)

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 87)

The Journal of the Visit to Kumasi of W. Huydecoper pg 24-25)

Journal of a Residence in Ashantee by Joseph Dupuis pg 70-71

Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee by Thomas Edward Bowdich pg 37

Precolonial African Diplomacy: The Example of Asante by Graham W. Irwin pg 89-90)

The Journal of the Visit to Kumasi of W. Huydecoper pg 53

Journal of a Residence in Ashantee by Joseph Dupuis pg 81

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 321)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 323-324)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 303)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg pg 604)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks 614-619)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 633-638)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 643-645)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 650- 658)

Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks pg 324)