Creating an African writing system: the Vai script of Liberia (1833-present)

“There are three books in this world—the European book, the Arabic book, and the Vai book”

A small West-African town located a short distance from the coast of Liberia, was the site of one of the most intriguing episodes of Africa's literary history. Inspired by a dream, a group of Vai speakers had invented a unique script and spread it across their community so fast that it attracted the attention many inquisitive visitors from around the world, and has since continued to be the subject of studies about the invention of writing systems.

The Vai script is one of the oldest indigenous west African writing systems and arguably the most successful. Despite the script's relative marginalization by the Liberian state (in favour of the roman script), and the Vai's adherence to Islam (which uses the Arabic script), the Vai script has not only retained its importance among the approximately 200,000 Vai speakers who are more literate in Vai than Arabic and English, but the script has also retained its relevance within modern systems of education.

This article traces the history of the Vai script from its creation in 1833, exploring the political and cultural context in which the script was invented and propagated in 19th century Liberia.

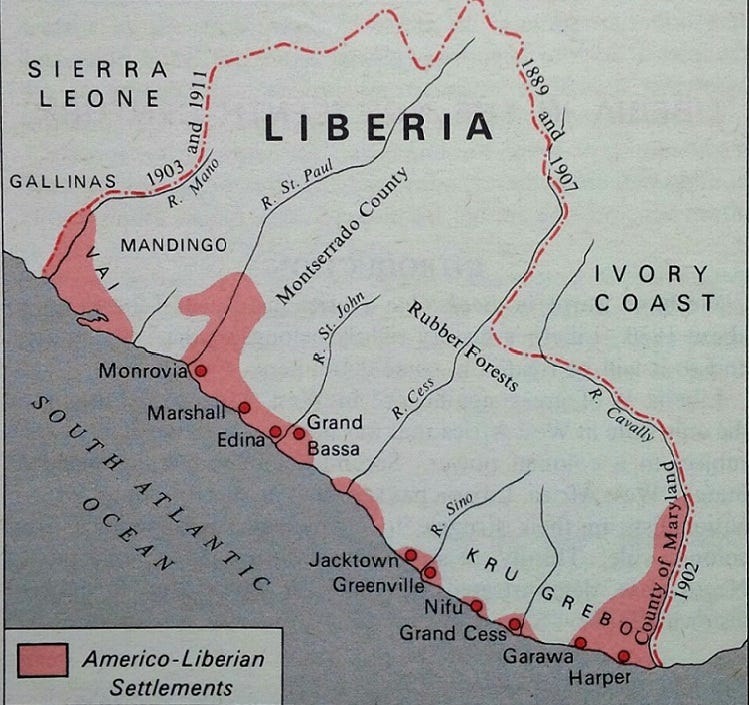

Map showing the present territory of the Vai people and the town of Jondu where the Vai script was invented

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The Vai in the political history of Liberia: trade, warfare and colonialism.

From the 14th-17th century, various groups of Mande-speakers who included the vai arrived and settled in the coastal hinterlands of what later came to be Liberia, as a part of a southward extension of trading networks that reached from the west African interior. Over the the 18th and 19th century, the Vai and their neighbors had established various forms of state-level societies often called confederacies in external sources.1

These states had primarily agro-pastoral economies, their populations were partially Islamized, and were also engaged in long distance trade with the interior states and the coastal settlements; exchanging commodities such as salt, kola, ivory, slaves, iron, palm oil and cotton. The salt trade in particular, had served as an impetus for the Vai’s gradual migration southwards.2

In the early 19th century, the Vai and other African groups near what would later become the city of Monrovia, underwent a period of political upheaval as the area became the target of foreign settlers comprised mostly of freed-slaves from the U.S. The establishment of a colony at Monrovia, was response to the growing abolitionist movement in the U.S, that was exploited by the “American Colonization Society” company, which undertook a largely unpopular resettlement program by moving a very small fraction of freed slaves to Liberia.3

Beginning in 1822, a tiny colony —which eventually numbered just over 3,000 people by 1847— was established at Monrovia and other coastal cities by the society using a combination force, barter and diplomacy to subsume and displace the autochthonous populations. Mortality for the settlers was as high as 50%, and by first decade of the 1900s, more than 80% of the coastal population was made up of acculturated Africans.4

Map of the Liberian colony in the late 19th century, most of the (unshaded) hinterland including the Vai territory to the west was only nominally with the colony’s influence before the 20th century.

The cultural environment of Cape mount county, Liberia: home of the Vai script’s inventor.

While there was a significant degree of "mutual acculturation" between the freed slaves and the African groups due to trade, intermarriage and cultural exchanges, as observed by one writer in 1880, that "along the Liberian coast the towns of the colonists and the natives are intermingled, and are often quite near to each other."5, the relationship between the two groups was also marked by ideological competition and warfare.6 This was especially evident as the Liberian colony expanded into cape mount county of the Vai in the 1850s, ostensibly to mediate the interstate wars between the Vai and neighboring groups 7

It's within this context that a Vai man named Duwalu Bukele Momulu Kpolo, and his associates invented a script for the Vai language. Bukele originally lived in the town of Jondu where he created and taught the script, before he moved to the town of Bandakoro, both towns were located in the modern Garwula District of Cape-mount county, Liberia8.

Bukele wasn’t literate in any script prior to the invention of Vai, and most accounts recorded by internal and external writers mention that he was barely able to speak English and wasn't familiar with writing it9. While the Americo-Liberian settlers had established Christian mission schools at the coast, neither Bukele nor his associates were Christian. Although Bukele later became Muslim around 1842 10 (Momulu is Vai for Muhammad), This conversion occurred nearly a decade after the script's invention in 1832/1833.11

The origin myth of the Vai script: Visions of people from afar.

An early account about the script’s invention approximately one year after its creation was recorded by a Christian missionary in march 1834; "An old man dreamed that he must immediately begin to make characters for his language, that his people might write letters as they did at Monrovia. He communicated his dream and plan to some others, and they began the work."12

In March 1849, another missionary named Sigismund Koelle met the script's inventor Bukele and his cousin Kali Bara, from whom he recorded a lengthy account of the script's invention. In a story recorded by Koelle by the inventor Bukele, the latter recounts a dream in which a "poro" man (poro = 'people from afar' in Vai which includes both Americo-Liberians and Europeans) showed him the script in the form of a book, with instructions for those who used the script to abstain from eating certain animals and plants, and not to touch the “book” when they are ritually unclean. Kali Bara on the other hand recounts a slightly different tradition, writing in his Vai book, he mentions that the script was invented after 6 Vai men (including himself and Bukele) had challenged themselves to write letters as good as the intelligent "poro".13

Later recollections recorded in 1911 about the scripts’ invention provide a slightly different version; that Bukele received the Vai “book” from a Spirit, and was instructed to tell Vai teachers that their only tuition should be palm wine, that would be ritually spilled before studies.14

Interpreting the exact circumstances of the script's invention as related in these accounts has been a subject of considerable debate. While the majority of the world's writing systems didn’t spontaneously materialize, a given society’s exposure to a writing system is by itself not a sufficient impetus for inventing a script. The vai had been familiar with the Arabic script used by their west African peers and immediate neighbors since the 10th century, and had been in contact with the European coastal traders with their Latin script, since the 16th century. However, the Vai writing system is a syllabary script (like the Japanese kana and Cherokee scripts) that is wholly unlike the consonantal Arabic script nor the alphabetic Latin script.15

Some scholars have explored the possible relationship between Vai and the contemporaneous Cherokee script as well as the identity of the “poro” man in tradition. Their show that there’s scant evidence that the most likely “poro” candidates; John Revey (an Americo-Liberian missionary active in the region in 1827) and Austin Curtis (a mixed native-American coastal trader), provided any stimulus for the invention of the script. The purported connection that these two men had with Bukele isn’t recorded in any contemporary account; its absent in Kali Bara’s lengthy Vai book, and it isn’t mentioned by John and Curtis themselves (despite both leaving records), nor is the connection made by any missionary of which more than a dozen wrote about the script16. The scholars therefore conclude that any link between Cherokee and Vai scripts "remains conjectural because the evidence is only circumstantial, with no conclusive direct link between the two scripts" and the “We have no doubt that Doalu Bukele was the "proper inventor" of the Vai script”.17

The role of the Vai king Goturu: Legitimating an invention

According to the account narrated by Bukele, he and his associates took their invention to the Vai king Goturu, and the latter he was impressed with it, declaring that the "this (Vai script) was most likely the book, of which the Mandingos (his Muslim neighbors) say, that it is with God in heaven, and will one day be sent down upon Earth", and that it "would soon raise his people (the Vai) upon a level with the Poros and Mandingos"18

Goturu later composed a manuscript in Vai containing descriptions of his wars, as well as moral apothegms with Islamic themes19, he also played an important role in the script’s early adoption by greatly encouraging the construction of schools to teach the Vai script20.

This leaves little doubt that the vision origin-myth of the Vai script, with its recognizable Islamic themes — from Muhammad’s divine revelation of the Koran, to the wudu purification ritual before touching it—, as well as the "poro" figure, were post-facto creations by the script's inventors and their king, to legitimate their innovation through divine revelation, as well as to enhance the prestige and political autonomy of king Goturu's state especially in relation to their “poro” neighbours.21

As in many cultures around the world, visionary rituals are part of the spiritual repertoire of West African tradition and belief systems, they lend "divine" authority to an invention and legitimate it, while enabling the inventors of the new tradition to deny its original authorship by attributing it to otherworldly beings, as a way of persuading potential adopters to accept it.22

Preexisting “archaic” writing systems and ideological competition in 19th century Liberia

Prior to the invention of the Vai script, there were preexisting graphic systems of “archaic”/proto writing used by the Vai and their neighbors, that was expressed in interpersonal communication, war, and divination rituals.23This preexisting corpus of logograms was drawn upon by Bukele for the creation of Vai characters, and is included in early accounts about the script which referred to these Vai logograms as “hieroglyphs” (discussed below), but they were gradually discarded as the Vai syllabary was standardized and acquired its fully phonetic character. 24

There is evidence that the degree of intellectual ferment in Vai territory at the time that the script was invented —stimulated by coastal and interior contacts (Americo-Liberian colonists with the Latin script, and Muslim teachers with the Arabic script)25— is in line with most of the accounts about the invention of the script and pride that the Vai people have of it.

A teacher of Vai in 1911 wrote about the script that “the Vais believe was taught them by the great Spirit whose favourites they are”26 ; and a researcher in the 1970s was told that; "There are three books in this world—the European book, the Arabic book, and the Vai book; God gave us, the Vai people, the Vai book because we have sense."27

Both of these statements echo the competitive ideological and intellectual milieu of 19th century Liberia that was remarked upon by external writers, and reveal the circumstances which compelled the Vai script's creators to demonstrate their sophistication and assert their political autonomy in relation to their literate neighbors; the ‘poro’ colonists and the Muslim scholars, to show them that the Vai were “book-people”28 as well. (Bukele's other name; ‘Kpolo’, means book in Vai29)

Bukele’s vision origin-myth also created an association between the Vai education with religious experience, and was strikingly similar to the kind of Muslim (and Christian) religious education which the Vai were familiar with from their neighbours. The vision’s inclusion of a “divinely” received book, the dietary taboos, and instructions against sacrilege/desecration of the Vai “book”, would have resonated among both Muslims and Christians in 19th century Liberia.30 While the traditions of ritually spilling palm wine before teaching the script were rooted in the Vai’s indigenous belief systems31.

The Vai writing system: the standardized and pre-standardized characters.

The Vai script is a syllabary script (ie: a writing system whose characters represent syllables), that contains 211 signs according to the standardized version completed in 1899 and 1962. The characters represent all possible combination of consonants and vowels in the Vai language, as well as seven individual oral vowels, two independent nasals [ã, ɛ̃], and the syllabic nasal [ŋ].32

Chart of the standard Vai syllabary

Before its standardization, the Vai script also contained approximately 21 logograms (ie; characters that represent complete words) , derived from an prexisting “pictorial code” used by the Vai to spell whole words and to represent discrete syllables33(hence; Logo-Syllabograms).

Between the 1840s and 1960s, these symbols, which were recorded in various accounts of atleast 15 different writers, had mostly been discarded in the process of standardizing the script. As one writer observed in 1933, the Vai script was by then "a purely phonetic syllabic script” even though "signs are occasionally found in Vai manuscripts which embody not a phonetic sound-sequence but a definite concept”.34

Chart showing the Vai logo-syllabograms documented by different writers.

Teaching the script: Vai education systems from 1833 to the present day

The teaching of the Vai script was conducted in purpose-built schools constructed by Bukelele and his associates in the town of Jondu by the year 1834. "They erected a large house in Dshondu (Jondu), provided it with benches and wooden tablets, instead of slates, for the scholars, and then kept a regular day-school ; in which not only boys and girls, but also men, and even some women learnt to write and read their own language. So they went on prosperously for about eighteenth months, and even people from other towns came to Dshondu, to make themselves acquainted with this "new book".35 Vai characters were written on paper, cloth, walls, furniture and other mediums primarily using dyes made from local plants.36

While Koelle’s account doesn't include exactly what was taught in the Vai schools, it's very likely that elementary education in the Vai script during the early 19th century was primarily acquired by letter writing and correspondence. Bukele and his associates had been impressed with the ability of their literate neighbors (especially the “poro”) to communicate over long distances37, and according to Kali Bara's account, the Vai script came about after they had challenged themselves to write letters to each other like the poro. Early missionary accounts that were recorded less than a year after the Vai script's invention also mention that the Vai "write letters and books"38.

In modern times, the elementary teaching of the Vai script primarily involves letter writing especially for trade and interpersonal communication, with classes taking place about 5 days a week over a few months, this time period being enough for a student to acquire a functional level of literacy. Depending on the occupation of the teacher and their student, other forms of teaching include record keeping (especially in long-distance trade and crafts like carpentry and construction), as well as in documenting history and composing religious literature.39

19th century Vai manuscript written by a student named Zoni Freeman to his teacher Dr. Imaa (Ms. U778 American Missionary Association Archives). The subject matter of the writing, which includes rhetorical questions that begin with "what is …" and "who is…" suggests it was written in a learning context.40

a carpenters plan, taken from a sketch made in the 1970s, the rooms are labeled using Vai script (eg “sleeping room” in the bottom figure), while the measurements use arabic numerals41

Vai Manuscripts:

One of the oldest documents written in the Vai script is "Book of Ndole," composed by Bukele's cousin, Kali Bara before 1849. Its an autobiographical account of his life, and also contains lengthy accounts of national and international events in the Cape mount region that are of historiographical nature (several copies were printed in the 1850s and one is currently at the Houghton Library of Harvard University).42

However, most written works of Vai are private compositions (such as the personal diary included below) and there are thus few works in the Vai script available publically that are reproduced in significant quantity, save for translations of religious stories and texts, as well as other forms of wall inscriptions and the occasional government posters.43

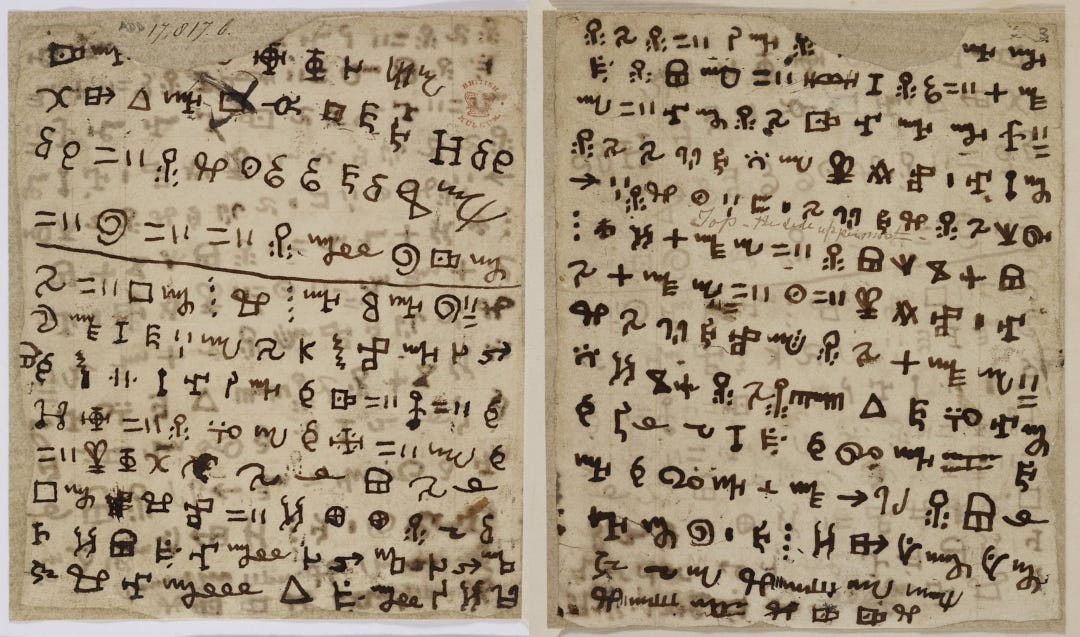

Vai manuscript collected in 1849, currently at the British Museum: MS 17817A, B44

Personal diary of Boima Kiakpomgbo, its earliest entry is dated 1913, its written in the vai script inside a blank accounts book45

Ceremonial horn with Vai inscriptions, early 20th century Liberia, private collection

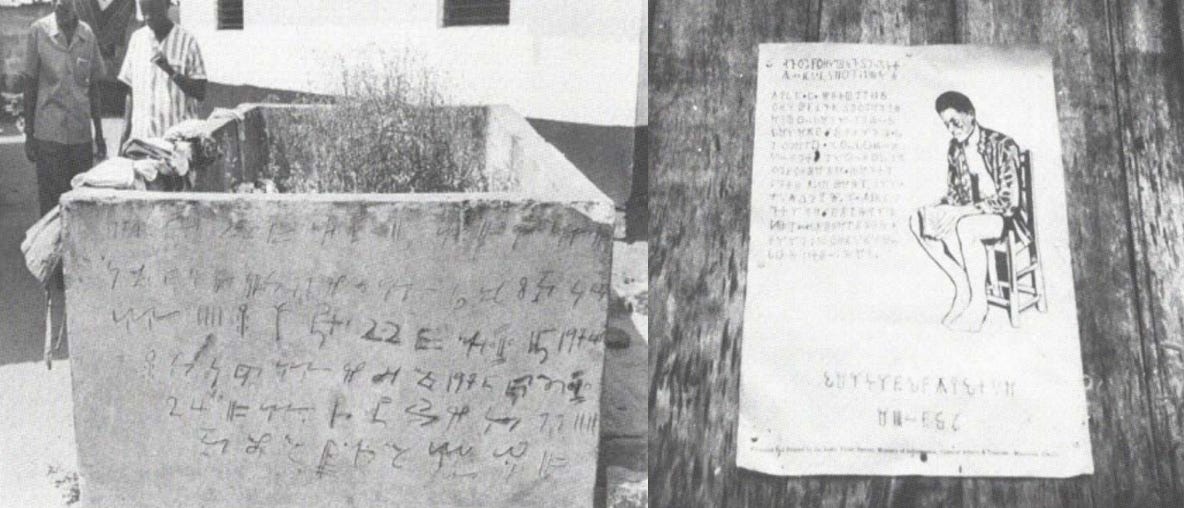

A tombstone and a government poster written in Vai script

The Vai education system: between the Muslim interior and Christian coast.

Aspects of Vai teaching in the 19th century could’ve been borrowed from the established Islamic education system of west Africa. The Liberian hinterland, like much of west Africa, was well integrated into the extensive scholarly networks, particularly of old Jakhanke diaspora. Local scholars based in towns such as Musadu, Vonsua, Bopolu, and Bakedu (all in western Liberia) provided much of the elementary education, and students moved for higher learning at Musadu as well as further north to Jenne and Timbuktu (in Mali), as well as to Timbo and Kankan (in Guinea). One scholar from Musadu in the 19th century was Ibrahima Kabawee who'd visited all the above mentioned towns.46

Atleast 25% of the Vai that Sigismund Koelle met in the 1849 were Muslims47, a figure has since risen to 90%,48 and while Bukele only converted to the religion at a later date, and even had a personal teacher (Malam) who engaged in a fierce religious debate with Koelle49, he and his peers would have been familiar with the Islamic education beforehand. As one external writer noted in 1827 that "every village" in the Cape Mount district had its Islamic teacher, with children being taught to read in Arabic script, and another writer noted in 1834 that "the zeal which the (Islamic) teachers manifest in extending it, and the diligence with which it is studied, exhibit a most encouraging aptitude for learning".50

While an Americo-Liberian missionary named John Revey had succeeded in establishing a short-lived Christian school in the cape mount region in 1827 that lasted about a year, and a few Vai men would had travelled to Monrovia and Freetown (in Sierra Leone) and exposed to similar church-schools, there was no Vai in the cape-mount interior who had been converted to Christianity by the 1840s, and the only known Vai student from the region briefly attended a coastal school in a rather opportunistic fashion51. The Christian form of education is therefore unlikely to have influenced Vai education during the early 19th century.

The Spread of Vai literacy: Formal and informal channels of learning

The early success of Bukele's schools was in part due to the support of a prestigious patron. In Bukele’s account, the inventors approached the Vai King Goturu with a gift of 100 parcels of salt each about 3-4ft long in order for him to support for their initiative (Bukele was part of an important trading family52). The king then requested Bukele and his associates to teach the Vai script in Jondu "and to make known his will, that all his subjects should be instructed by them".53

But after about 18 months (around 1835), Jondu was sacked in a war with a neighboring state, and the students and their teachers moved to other regions. Jondu was resettled shortly after to become the modern town, but the Vai teachers resumed their activities in 1844 at a nearby town of Bandakolo. And by 1849 "all grown-up people of the male sex are more or less able to read and to write, and that in all other Vei towns there are at least some men who can likewise spell their "country-book."54

While the area around Bandakolo was again affected by war, the region’s intermittent conflicts are unlikely to have significantly affected the spread of Vai literacy, which continued to be attested in the late 19th and early 20th century and was increasingly propagated through less institutionalized methods55. A remarkable example was a Vai ruler of a small state near the coast in 1911, who was unfamiliar with English, but could read and comment on Homer’s Iliad translated in the Vai script.56

A study in the early 1970s in the Cape Mount County found that among the literate Vai men, 58% were literate in Vai script and other scripts, compared to 50% in Arabic script and 27% in the English.57 Making Vai the most successful indigenous script in West Africa.

A rubber plate used to print the Vai syllabary (image flipped to the side)

Conclusion: the Vai writing system in Liberian history.

The Vai script was the product of the exigencies of political and ideological competition in early 19th century Liberia, as well as the inventiveness of Bukele and his associates, who drew inspiration from known writing systems and the preexisting pictorial culture to develop their own unique script. Once established, the Vai writing system met practical record keeping and communication needs but also allowed its users to to circumscribe alternative politico-religious formations in opposition to the discourses of Liberian colonial administrations.

The Vai script served ideological values in traditional activities, functional values in long-distance trade, and political values in maintaining the Vai’s autonomy in a region at the nexus of foreign colonization and local resistance. The Vai insisted on acquiring literacy in their own script, and accomplished this despite the volatile political landscape of 19th century Liberia, enabling them to attain the highest rate of literacy of any indigenous West-African script.

NSIBIDI is West-Africa’s oldest indigenous writing system, read about its history on our Patreon

The Mane, the Decline of Malnd Mandinka Expansion towards the South Windward Coast by AW Massing pg 45, 43-44

African-American Exploration in West Africa by James Fairhead pg 306-331)

Liberia and the Atlantic World in the Nineteenth Century by W.E Allen pg 21-22, 31)

African-American Exploration in West Africa by James Fairhead pg 13-14)

Liberia and the Atlantic World in the Nineteenth Century by W.E Allen pg pg 31)

African-American Exploration in West Africa by James Fairhead pg pg 285-286)

African Resistance in Liberia: The Vai and the Gola-Bandi by Monday B. Abasiattai, pg 48

Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script by Konrad Tuchscherer 441-442)

Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 448)

Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country of West Africa by by Sigismund Koelle pg 23, 26)

Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 438

Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 438)

Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 444-445,449)

The Vai people and their syllabic writing by Massaquoi pg 465

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 32, Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 458)

only a single anonymous source makes a claim —25 years after the script’s invention— that it was Revey who inspired it and taught Bukele, but this was a mere supposition as Revey didn’t teach Bukele, neither did he mention anywhere in his accounts about introducing a new script, a project that was infact tried by one of his peers in 1835, see; Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 474.

Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 483- 484, 452.

Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country of West Africa by Sigismund Koelle pg 24)

Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 449 n. 61)

Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country of West Africa by Sigismund Koelle pg 24

Dreams of scripts: Writing systems as gifts of God by Robert L. Cooper pg 223, The invention, transmission and evolution of writing: Insights from the new scripts of West Africa by Piers Kelly pg 202)

Dreams of scripts: Writing systems as gifts of God by Robert L. Cooper pg 223, The invention, transmission and evolution of writing by Piers Kelly pg 204

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 266

The invention, transmission and evolution of writing by Piers Kelly pg 204, The Vai people and their syllabic writing by Massaquoi pg 465

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 265

The Vai People and Their Syllabic Writing by Momolu Massaquoi pg 459

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 31)

the term 'book-people’, ‘book-person’ and ‘book-palaver’ is encountered alot in west African accounts and local languages and it generally refers to literate people; initially Muslim Africans but also Christian Europeans, see: African-American Exploration in West Africa by James Fairhead pg 316, Cherokee and West Africa by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 445, Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country by Sigismund Koelle pg 26

Cherokee and West Africa by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 451, The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 317

invention, transmission and evolution of writing: Insights from the new scripts of West Africa by Piers Kelly pg 193)

Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country of West Africa by Sigismund Koelle pg 25

Distribution of complexities in the Vai script by Andrij Rovenchak pg 3, The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 32)

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 265-266

invention, transmission and evolution of writing: Insights from the new scripts of West Africa by Piers Kelly pg 193, The fate of logosyllabograms in the Vai script by Piers Kelly, 1834-2005

Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country of West Africa by Sigismund Koelle pg 24

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 240

Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country of West Africa by Sigismund Koelle pg 23

Cherokee and West Africa by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 448-445)

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 65-66, 71-82)

A Study of Two 19th Century Vai Texts by T. V. Sherman, C. L. Riley

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 78

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 79

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 78-82)

digitized on this blog , translation; “The Diary of Boima Kiakpomgbo from Mando Town (Liberia)” by Andrij Rovenchak

African-American Exploration in West Africa by James Fairhead pg pg 314-318)

Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country of West Africa by Sigismund Koelle pg 25)

Contrastive Rhetoric: Cross-Cultural Aspects of Second Language Writing By Ulla Connor pg 103

Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country of West Africa by Sigismund Koelle pg 27)

Cherokee and West Africa by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 454-455)

Cherokee and West Africa by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 457).

Cherokee and West Africa by Konrad Tuchscherer pg 447

Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country of West Africa by Sigismund Koelle pg 24)

Narrative of an Expedition Into the Vy Country of West Africa by Sigismund Koelle pg 24-25)

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 267

The Vai People and Their Syllabic Writing by Momolu Massaquoi pg 462-467

The psychology of literacy by Sylvia Scribner pg 63-64)

Great story, great read