Economic growth and cultural syncretism in 19th century East Africa: Trade and Swahili acculturation on the African mainland

On bi-directional exchanges between the east african mainland and coast

Much writing about 19th-century East Africa historiography has been distorted by the legacy of post-enlightenment thought and colonial literature, both of which condemned Africa to the periphery of universal history. Descriptions of East-African societies were framed within a contradictory juxtaposition of abolitionist and imperialist concepts that depicted Africa (and east Africa in particular), as a land of despotic Kings ruling over hapless subjects, and whose slaves were laden with ivory and sold to brutal Arabs at the coast. Trade and cultural exchanges between the coast and the mainland were claimed to be unidirectional and exploitative for the latter, and given the era’s “climate of imperialism”, European conquest became in this guise an enlightened campaign for civilization on behalf of an African mainland subjugated by a rapacious Orient; sentiments that were best expressed in the east-African travel account of the American “explorer” Henry Morton Stanley's "Through the dark continent"1

While most of the erroneous literature contained in such travelogues and later colonial history has been discarded by professional historians, some of the old themes about the economic dynamics of the ivory trade, the forms of labor used in east African societies, the nature of cultural syncretism and the form of political control exerted by the Oman sultanate of Zanzibar over the Swahili cities and the coast have been retained, much to the detriment of of any serious analysis of 19th century east African historiography.

This article provides an overview of 19th century east African economies, trade, labour and cultural syncretism, summarizing the bidirectional nature of interactions and exchanges through which east Africans integrated themselves into the global economy.

Map of late 19th century east Africa showing the the caravan routes in and cities mentioned below

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The east African coast in the 19th century; from the classical Swahili era to the Omani era.

Until the 19th century, the Swahili city-states were largely politically autonomous, most of them having peaked in prosperity during their classical era between the 11th and 16th century. The advent of the Portuguese in 1498, who for a century tried to impose themselves over the independent and fiercely competitive Swahili city-states, coincided with a radical shift in the fortunes of some of the cities and the collapse of others. To preserve their autonomy, the Swahili cities forged shifting alliances with various foreign powers including the Ottomans in 1542 and the Omani-Arabs in 1652, the latter of whom were instrumental in expelling the Portuguese in 1698 but who were themselves expelled by the Swahili by the 1720s. It wasn't until the ascendance of the Oman sultan Seyyid Said in 1804 that a concerted effort was made to take over the northern and central Swahili coast; with the capture of; Lamu in 1813, Pemba in 1822, Pate in 1824, and Mombasa in 1837, afterwhich, Seyyid moved his capital from Muscat (in Oman) to Zanzibar in 1840, and expelled the last Kilwa sultan in 1843. The newly established Zanzibar sultanate, doesn't appear to have desired formal political control beyond the coast and islands and doubtless possessed neither the means nor the resources to achieve a true colonization of the coastal cities, let alone of the mainland.2

A common feature of coastal economic history during the Sultanate era was the dramatic expansion in trade and coastal agriculture, but with the exception for clove cultivation, most of the elements (such as Ivory trade and extensive plantation agriculture), and indeed the beginnings of this growth were already present and operating in the 18th century Swahili cities, especially at Lamu, Mombasa, Kilwa, Pate. The the establishment of the Sultanate only gave further impetus to this expansion.3 Seyyid and his successors were “merchant princes”, who engaged in trade personally and used their profits and customs dues to advance their political interests, Their success lay in commercial reforms that benefited the cities' merchant elites, such as encouraging financiers from Gujarat (India) —who'd been active in Oman and some of the Swahili cities— to settle in Zanzibar, where their population grew from 1,000 in 1840 to 6,000 by the 1860s4, Seyyid also signed treaties with major trading nations (notably the US and UK) which turned Zanzibar into an emporium of international commerce, and the cities of Lamu, Mombasa, also flourished as their older transshipment economic system expanded.5

The sultanate’s rapidly evolving consumer culture evidenced the deployment of global symbols in the service of local image-making practices. Sayyed relaxed older status codes and encouraged a culture of consumption more indulgent and ostentatious than that of the classical Swahili city-states and Oman. Coast-based commercial firms, most of which were subsidiaries of Indian financial houses, began offering generous lines of credit to caravan traders and coastal planters, fueling the acquisition of imported consumer goods (such as clothing, jewelry, and household wares ) among coastal residents of all socioeconomic backgrounds, both for personal use and for trade to the African mainland6.

Consumer culture became a finely calibrated means of social/identity negotiation in a changing urban environment, offering a concrete set of social references for aspiration, respect, honor, and even freedom, due to the fluctuating forms of status representation. This ushered in an era of unrestrained consumption such that the virtually all the population from the elite to the enslaved were fully engaged in the consumer culture and status-driven expression. symbols of (classical Swahili) patrician status such as umbrellas, kizibaos (embroidered waistcoat), kanzus (white gowns), expensive armory, including swords and pistols, canes and fezz-hats which 16th century observers remarked as status markers for Swahili elites7, were now common among non-elite Swahili and even slaves who used them as symbols of transcending their enslaved status8. the enslaved used their monthly earnings of $3-$10 to purchase such, and they consumed around 22% of all coastal cloth imports in the late 19th century, constituting roughly 10 meters per slave, (a figure higher than the mainland’s cloth import percapita of 2 meters)9. Their status in Zanzibar being similar to that across the continent; "the difference between free and slave was defined by their social status more than by the nature of their work or even the means of payment"10

The acquisition of what were once status markers by the lower classes encouraged the Arab elite and Swahili elite to purchase even more ostentatious symbols of distinction including clocks, books, mirrors, porcelain, and silk cloths. This consumer culture provided a major impetus for extensive trade both into the mainland and across the ocean and even a person of relatively meager means could travel abroad, trade, or otherwise accumulate signs of distinction.11

Cloth exports to East Africa from the United Kingdom, United States, and Bombay, 1836–1900 (mostly to Zanzibar and related cities, but also Mozambique)12

Interior view of a mansion in Zanzibar, circa 1880s. (Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum)

Swahili patricians sitting in state in a richly decorated reception room in Lamu city, Kenya, 1885, ruins of a swahili house in Lamu with Zidaka (wall niches) for holding porcelain, room of a swahili patrician with porcelain display and books.

Cloth, ivory and wage labourers; trade and exchanges between the coast to the mainland.

Cloth:

Cloth was the primary export item into the mainland since its low weight and relatively high sale price compared to its purchase price made it the most attractive trade item over the long distance routes. For most of the 19th century, the majority of this cloth was merikani (American), preferred for its strong weave, sturdy quality and durability as cloth currency, which were all qualities of locally-produced cloths, in whose established exchange system the merikani was integrated, and sold, alongside glass-beads and copper-wire (for making jewelry), all of which were exchanged for ivory from the mainland markets13.

The vast majority of imported cloth and locally manufactured cloth stayed at the coast, due to; transport costs (from porters), natural price increase (due to its demand), and resilience of local cloth production in the mainland, all of which served to disincentivize caravan traders from dumping cloth into the mainland despite cloth supply outstripping demand at Zanzibar14. The latter restriction of supply was also mostly to maintain an advantage for the coastal traders and make the trade feasible, eg in 1859, the prices of a 1 meter merikani was at $0.14 at Zanzibar, but cost $0.75 at Tabora (in central Tanzania), and upto $1.00 at Ujiji (on lake Tanganyika), conversely, 16kg of ivory could be bought at Tabora for 40 meters of merekani (worth $3.20 at Zanzibar), then sold to global buyers at Zanzibar for $52.50 (worth 660 meters at Zanzibar).15

Cloth production in the late 19th century German east africa (Tanzania, Rwanda, Burudi), imported cotton cloths were mostly consumed in cotton-producing regions in the western regions like Ufipa as well as non-cotton producing regions in the northwest.

Porters and highway tribute:

But a significant portion of the profits were spent in the high transport costs of hauling ivory from the mainland, partly due to the heavy tributary payments levied by chiefs along the way (as large centralized states were located deep into the mainland), and the use of head porterage since draught animals couldn't survive the tse-tse fly ridden environment. The latter enterprise of porterage created some of east Africa's earliest wage laborers who were paid $5-$8 per month16 or attimes 18-55 meters of cloth per month, and thus consumed upto 20% of Zanzibar's cloth imports.17

Criss-crossing the various caravan trade routes and towns, these porters represented one of the most dynamic facets of the coast-mainland trade, without whom, "nothing would have moved", no trade, no travel and no "exploration" by anyone from the coast —be they Swahili, or Arab, or European— would have been undertaken18. It was these relatively well-paid porters, whose floating population numbered between 20,000-100,000 a month, who carried ivory tusks to Zanzibar and cloth into the mainland markets, that European writers would often intentionally (or mistakenly) identify as slaves and greatly exaggerate the supposed “horrors” of the ivory trade which they presumed was interrelated with slave trade, wrongly surmising that these porters were sold after offloading their tusks at the coast19.

These intentionally misidentified porters became the subject of western literature to justify colonial intervention, to remove the presumed African transport “inefficiencies” and exploit the mainland more efficiently, despite both 19th century European explorers, and later colonists being “forced” to rely on these same porters, and arguably expanding the enterprise even as late as the 1920s. These porters were often hired after complex negotiations between merchants and laborers at terminal cities such as Bagamoyo, and they could demand higher wages by striking forcing the caravan leaders to agree to their terms. (the explorer Henry Stanley found out that beating the porters only achieved negative results)20

Porters encamped outside Bagamoyo city, with bundles of cloth stacked against coconut palms, 1895 illustration by Alexander Le Roy (Au Kilima-ndjaro pg 85)

Ivory caravan in Bagamoyo, ca. 1889 (Historisk Arkiv, Vendsyssel Historiske Museum, Hjorring, Denmark)

Ivory trade:

It was ivory, above all commodities, that was the most lucrative export of the coastal cities and arguably the main impetus of the Mainland-coastal trade. For most of the 19th century save for the decade between 1878-1888, ivory exports alone nearly equaled all other exports of the east African coast combined; and this includes cloves (for which Zanzibar had cornered 4/5ths of the global production), gum-copal, rubber and leather21. Zanzibar’s export earnings of ivory (sold to US, UK and (british) India), rose from $0.8m in 1871 to $1.9m in 1892, largely due to increasing global prices rather than increased quantity22.

In the mid to late 19th century, a growing western middle class began to express a growing demand for the high quality and malleable East African ivory, as ivory-made luxury products and carved figures became one of the symbols of a high standard of living. More demand for East african ivory also came from consumers in India, where ivory-made jewelry was an important part of dowry23. But the ivory demand was never sufficiently met by east african supply and global prices exploded even as imports rose. Elephant populations had been prevalent across much of the east African mainland including near the coast inpart due to low demand for ivory in local crafts industries (most mainland societies preferred copper and wood for ornamentation and art). But the 19th century demand-driven elephant hunting pushed the ivory frontier further inwards, first from Mrima coast near Zanzibar, to Ugogo and Nyamwezi in central Tanzania, then to the western shores of lake Victoria and Rwanda-Burundi, and finally to eastern Congo, and the caravans moved with the advancing frontier24. As the ivory frontier moved inwards, prices of ivory in mainland markets rose and all market actors (from hunters to middlemen to porters to mainland traders to chiefs to final sellers at the coast) devised several methods to mitigate the falling profits, coastal merchants during the 1870s and 1880s began to employ bands of well-armed slaves as ivory hunters, which minimalized commodity currency expenditures and also reduced the access of independent local ivory hunters25.

Its important to note that while Ivory was important to Zanzibar’s economy, its trade wasn’t a significant economic activity of the mainland states26, and the cotton cloth for which it was exchanged never constituted the bulk of local textiles nor did it displace local production, even in the large cotton-producing regions like Ufipa in south-western Tanzania which was crossed by the central caravan routes.27

Share of Ivory exports vs coast-produced exports (cloves, gum-copal, rubber, etc) from East Africa, 1848–1900. (these are mostly figures from Zanzibar and its environs, as well as Mozambique)28

two men holding large ivory tusks in zanzibar

Brief note on slave trade in the south routes, and on the status of slavery in the central caravan route.

While the vast majority of laborers crisscrossing the northern and central caravan routes were wage earning workers, there were a number of slaves purchased in the mainland who were either retained internally both for local exchanges with slave-importing mainland kingdoms (which enabled them freed up even more men to become porters29), or retained as ivory hunters and armed guards, and thus remained largely unconnected to the coast.30 There was a substantial level of slave trade along the southern routes from lake Malawi and from northern Mozambique that terminated at kilwa-kivinje (not the classical kilwa-kisiwani), which is estimated to have absorbed 4/5th of all slaves31. Zanzibar’s slave trade grew in the mid-1850s, and the island’s slave plantations soon came to produce 4/5ths of the world’s cloves32, and while Zanzibar was also a major exporter of Ivory, gum-copal, rubber and leather, it was only cloves that required slave labor often on Arab-owned plantations33. The dynamics of slave trade in the southern region worked just like in the Atlantic, with the bulk of the supply provided by various groups from the mainland who expanded pre-existing supplies to the Portuguese and French , to now include the Omanis, and in this process, it rarely involved caravans moving into the mainland to purchase, let alone “raid” slaves.34

The low level of slave trade in the central and northern routes was largely due to the unprofitability of the slave trade outside the southern routes, because the longer distances drastically increased slave mortality, as well as because of the high customs duties by the Zanzibar sultans levied on each slave that didn't come from the south-eastern route, both of which served to disincentivize any significant slave imports from the northern and central routes, explaining why the virtually all of caravans travelling into the region focused on purchasing ivory.35

Identifying the Swahili on the Mainland, and Swahili Arab relations under the Zanzibar sultanate.

Scholars attempting to discern the identities of the coastal people in the mainland of east Africa face two main challenges; the way European writers identified them within their own racialized understanding of ethnic identities (as well as their wider political and religious agenda of; colonization, slave abolition, and Christian proselytization which necessitated moralizing), and the inconsistency of self-identification among the various Swahili classes which were often constantly evolving. The Swahili are speakers of a bantu language related to the Majikenda, Comorians and other African groups, and are thus firmly autochthonous to east-central african region36.

Until the 19th century, the primary Swahili self-identification depended on the cities they lived (eg waPate from Pate, waMvita from Mombasa, waUnguja from Zanzibar, etc), the Swahili nobility/ elites referred to themselves as waUngwana, and referred to their civilization as Uungwana, and collectively considered themselves as waShirazi (of shirazi) denoting a mythical connection to the Persian city which they used to legitimize their Islamic identities. “The word uungwana embodied all connotations of exclusiveness of urban life as well as its positive expressions. It specifically referred to African coastal town culture, even to the exclusion of 'Arabness'“. The Swahili always "asserted the primacy of their language and civilization in the face of Arab pretensions time and time again"37, as the 18th century letters from Swahili royals of Kilwa that spoke disparagingly of interloping Omani Arabs made it clear.

But this changed drastically in the 19th century as a result of the political and social categories generated by the rise of the Zanzibar Sultanate, which created new ethnic categories that redefined the self-identification among the Swahili elites and commoners vis-a-vis the newcomers (Oman Arab rulers, Indian merchants, mainland allies, porters and slaves) with varying level of stratification depending on each groups’ proximity to power. The old bantu-derived Swahili word for civilization “uungwana” was replaced with the arab-derived ustaarabu (meaning to become Arab-like), and as the former self-identification saw its value gradually diminished beginning in the 1850s. The influx of freed and enslaved persons, who sought to advance in coastal society by taking on a "Swahili" identity, pushed the Swahili to affirm their "Shirazi" self-identification and individual city identities (waTumbatu, waHadimu, etc38). Its therefore unsurprising that the European writers were confused by this complex labyrinth of African identity building.

The Omani conquest and ensuing political upheaval resulted in tensions between some of the Swahili elites who resisted and the Arabs seeking to impose their rule, this resulted in the displacement of some Swahili waungwana and caused them to emigrate from island towns to the rural mainland, where they undertook the foundation of new settlements.39 In the mainland, the meaning of waungwana changed according to location, underscoring the relative nature of the identity, where in its farthermost reaches in eastern congo, everyone from the coast was called mwungwana as long as they wore the coastal clothing and were muslim. The concept of uungwana became so influential that the Swahili dialect in eastern congo is called kingwana.

As a group, Swahili and waungwana were influential in the mainland partly because they outnumbered the Arabs despite the latter often leading the larger caravans. The broader category of waungwana influenced mainland linguistic cultural practices more than Arabic practices did, and the swahili were more likely to intermarry and acculturate than their Arab peers. By 1884, a British missionary west of lake Tanganyika lamented the synchretism of Swahili and mainland cultures in eastern congo that; "it is a remarkable fact that these zanzibar men have had far more influence on the natives than we have ever had, in many little things they imitate them, they follow their customs, adopt their ideas, imitate their dress, sing their songs, I can only account for this by the fact that the wangwana live amongest them".40

Identifying the Swahili on the mainland.

Despite the seeming conflation of the Swahili and the Arabs in the interior, the reality of the relationship between either was starkly different as tensions between both groups of coastal travelers in the mainland were reflected in their contested hierarchies within the moving caravans as well as in the bifurcated settlements in their settlements on the mainland which were “self segregated”.

An example of these tensions between the swahili and arabs was displayed in the caravans of Richard Burton and Hannington Speke 1856-1859 which was beset by a dispute arguably bigger than the more famous one between the two explorers. The conflict was between Mwinyi Kidogo, a Swahili patrician who was the head of the caravans’ armed escort, and Said Bin Salim, the Omani caravan leader appointed by the Zanzibari sultan. Kidogo had extensive experience in the mainland, had forged strategic relationships with the rulers along the trade routes and came from an important coastal family, while the latter was generally inexperienced.

Throughout the journey, Salim attempted to assert his authority over Kidogo with little success as the latter also asserted his own high-born status, and proved indispensable to everyone due to his experience, being the only leader in the caravan who knew the risks and obligations faced, such as forbidding the Europeans from paying high-tolls because such a precedent would make future caravans unprofitable. Salim was eventually removed by Burton on the return trip and replaced with a man more friendly with Kidogo. The Sultan would later appoint Salim as his representative at Tabora (though he was forced out later by his Arab peers and died on the mainland), while Kidogo continued to lead other caravans into the mainland.41

Salim’s house in Tabora built in the 1860s, later used by David Livingstone

Opening up the coast to trade; Mainland-Coastal interface in the mid 19th century by the Nyamwezi and Majikenda.

The Swahili city-states had for long interacted with several coastal groups before the 19th century, but from the 13th to 16th century, these exchanges were limited to the southern end of the coast through the port of Sofala in mozambique from which gold dust obtained in great Zimbabwe was brought by shona traders to the coast and transshipped to Kilwa and other cities, this trade was seized by the Portuguese in the 16th century, prompting the emergence of alternative ports (eg Angoche), the appearance of alternative commodities in Swahili exports (eg Ivory), and the appearance of other mainland exporters (eg the Yao). But it wasn't until the early 19th century that large, organized and professional groups of commodity exporters from the mainland such as the Nyamwezi and Majikenda begun funneling commodities into the coastal markets in substantial quantities in response to their burgeoning global demand.42

In the central caravan routes, the Nyamwezi groups augmented older, regional trade routes of salt and iron across central Tanzania, linking them directly to the Swahili markets, and from the latter they bought consumer goods, the surplus of which they transferred to mainland markets and in so doing, pioneered routes that were later used by coastal traders43. The Nyamwezi, who remained formidable trading competitors of the Arabs and the Swahili merchants on the mainland, often kept the coastal traders confined to towns such as Tabora and Ujiji, where few Nyamwezi were resident as they carried out regional trade along shorter distances.44 The Nyamwezi constituted the bulk of the porters along the central caravan routes, and contrary to the polemical literature of the western writers, they weren't enslaved laborers but wage earners, nor could enslaved laborers substitute them. As the historian Stephen Rockel explains, "the inexperienced, demoralized, sick, and feeble captives who frequently absconded were hopelessly inefficient and could not be used by traders for a round-trip"45.

The northern caravan routes were dominated by the Majikenda who supplied Swahili cities like Mombasa and Lamu with their own produce (ivory, gum copal, grain), But the Swahili (and later Arab) traders resident in Mombasa only occasionally went into the Majikenda hinterland especially when the ivory demand was higher than expected. besides this, the Mijikenda markets traded in relatively bulky goods-goods that were being brought to Mombasa and there was thus little reason to frequent their mainland markets before the mid 19th century.46

Wage rates for Nyamwezi porters per journey, 1850-190047

It was this well-established caravan culture, which was basically Nyamwezi in origin, that provided the foundation for coastal merchants to organise their own and served as the foundation of the multidirectional cultural influences that would result into the spread of Swahili culture into the mainland.48

By the 1850s many of the basic characteristics of caravan organization and long-distance porterage were well established including the employment of large corps of professional porters. Trade routes sometimes changed-in response to conflict, refusal of mainland chiefs to allow passage, or general insecurity. In this instances, the outcome of such conflict very much depended on the diplomatic skills of caravan leaders and local chiefs because the balance of power, which-with the exception of very well-armed caravans, usually lay with the peoples of the mainland.49 or as one writer put it "their safety, once in the interior, depended on their good relations with native chiefs”, and there are several examples of caravans and caravan towns which were annihilated or nearly destroyed over minor conflicts with the societies enroute especially with conflicts resulting from food and water provisions50.

The latter reason explains why the caravans opted to pay the relatively expensive tributes to numerous minor chiefs along the trade route; the cumulative cost of which, later European explorers —who were unaccustomed to the practice— considered "an irritating system of robbery"51. Further contrary to what is commonly averred, the guns carried by the caravan's armed party didn't offer them a significant military advantage over the mainland armies nor against warriors from smaller chiefdoms (as the Zanzibar sultan found out when his force of 1,000-3,000 riflemen was defeated by the Nyamwezi chieftain Mirambo and the Arab settlement at Tabora was nearly annihilated); and neither did fire-arms guarantee the military superiority of the mainland states which bought them from the caravans, such as Buganda and Wanga, as its covered below.

From the coast to the mainland: Swahili costal terminals to Swahili settlements, Bagamoyo to Ujiji.

Among the coastal terminals of the ivory trade, which extended from Lamu, Mombasa, Saadani, Panga, to Bagamoyo, it was the last that was the least politically controlled by the Zanzibar sultans but relatively one of the most prosperous.

The city of Bagamoyo was established by the Zaramo (from the mainland), in alliance with the Swahili of the shmovi clan, the latter of whom had been displaced from the classical city of Kaole that had been inadvertently destroyed by the Sultan Seyyid in 1844, in an attempt to establish a direct system of administration subordinate to Zanzibar. Bagamoyo however was only nominally under the Sultan’s control and the administration of the city was almost entirely under local authorities after the latter repeatedly asserted their autonomy, something the explorers Henry Stanley and Lovett Cameroon found out while attempting to leverage the Sultan’s authority to outfit their own caravans into the mainland from the city.52

Bagamoyo was also the city which exercised the most significant political control over its adjacent hinterland, negotiating with the Zaramo and the Nyamwezi for the supply of ivory, caravans started arriving to the city around 1800 and departing from it into the mainland by the early 19th century, it became one of the most important terminals of the trade and the preferred place of embankment for ivory caravans through the central route. 53Bagamoyo had a floating population of 12,000 ivory porters a week compared to a permanent population of 3,000, its vibrant markets, financial houses and ivory stores led to the emergence of a wealthy elite.54

For most of the 19th century, gum copal (from the coastal hinterland) and ivory (from the mainland) were the two main articles of trade from Bagamoyo55. The city's ivory stock was reportedly 140,000 kg in 188856, compared to Mombasa's ivory exports 8,000kg (in 188757) and Zanzibar's ivory exports of 174,000kg (in 186258 )

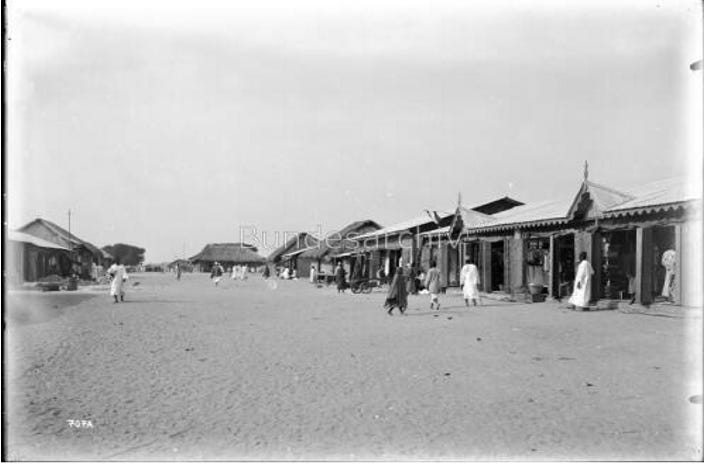

Bagamoyo Street scene with stone houses, ca. 1889 (Vendsyssel Historiske Museum), coffee house in Bagamoyo with African patrons, early 1900s (german federal archives)

Carravan movement into the northern route of what is today modern Kenya was rather infrequent, In 1861, a coastal trader was found residing 20 miles inland at a large village beyond Kwale, this trader was identified as Nasoro, a Swahili and caravan leader.59 It appears the northern route was still dominated by mainland traders moving to the coast rather than coastal caravans moving to the mainland, By the 1850s, coastal influences were spreading among the Segeju of the Vanga-Shimoni area (near the present-day border between Kenya and Tanzania) due to intermarriages with the Vumba Swahili of Wasini Island (south of Mombasa), and the Segeju allowed the Vumba to establish themselves on the mainland peninsula60. These segeju latter hired themselves out as porters much like the Nyamwezi did in the central route but to a lesser extent as the nothern routes were less active.

“Coastal” towns on the Mainland: Tabora, Ujiji and Msene

It was at Tabora, Msene and Ujiji in the central mainland that the largest coastal settlements developed. Tabora, some 180 miles south of Lake Victoria and 200 miles east of Lake Tanganyika, was strategically located in a well-watered fertile region at the crucial junction where the central trade route split into two branches, one proceeding west to Ujiji, the other north through Msene, to the western shores of Lake Victoria in the kingdom of Karagwe, to terminate at the lakeport of Kageyi which connected to the Buganda kingdom. Ujiji, located on the eastern shores of Lake Tanganyika, was an important staging point for trade across the lake into the eastern D.R.C61. Carravans from all of these towns primarily terminated at the coastal city of Bagamoyo

While coastal traders travelling through the old central routes had already reached the western side of Lake tanganyika by the 1820s, Tabora (Kazeh) wasn’t established until 1852 with permission from the Nyamwezi chief of Unyanyembe62, it had by the 1860s grown into the most important of the Muslim settlements of the central mainland, Most of the coastal traders who lived in Tabora—were Arabs from Zanzibar, of Omani origins, Swahili traders settled in Msene and reportedly had a “natural aversion” to the Arabs of Tabora, this animosity was due to the social tensions that had developed along the coast (as explained above), tensions that led to the establishment of bifurcated settlements in the mainland in which Arabs and Swahilis lived separately. Msene which was located 70 miles northwest of Tabora, and became a principal trading post of the region leading into the kingdoms of Rwanda, Karagwe, Nkore and Buganda. In Msene’s markets, coastal goods (especially cloth, and glassbeads) were exchanged for mainland commodities (primarily ivory as well as grain and cattle), its vibrancy was such that "the temptations of the town rendered it impossible to keep a servant within doors"63.

Despite the rather large population of coastal traders, there was an apparent general lack of interest among most them in spreading their religion. Few local Africans seem to have adopted Islam, and those who did generally numbered among the immediate entourage of the merchants64. In the 1860s and 70s, the rise of Mirambo and his conflicts with the merchants of Tabora over unpaid tributes led to several wars with the coastal merchants and disruption of caravan trade, which enabled the emergence of Ujiji. The town's resident merchant colony was governed by a Swahili chief, Mwinyi Mkuu, whose brother Mwinyi Kheri had married the daughter of the king of Bujiji, After acquiring the status of a chief under the ruler of Bujiji, Mwinyi Kheri came to control most of the trade that passed through Ujiji. When Henry Stanley visited Ujiji in 1872, he described "the vigorous mingling of regional and long-distance trade taking place there." and By 1880 Ujiji was home to 8,000 inhabitants.65 many of whom were establishing themselves in the Kingdoms of the mainland such as Karagwe and Buganda.

street scene in Tabora, 1906, (German federal archives)

The Great Lakes kingdoms and the east African coast: Trade and swahili cultural syncretism in the 19th century.

Map of the Great lakes kingdoms in the late 19th century66

Buganda and the Swahili

The first itinerant coastal traders arrived in Buganda as early as 1844 during Kabaka (King) Suuna II's reign (r. 1832-1856), following an old trade route that connected the Nyamwezi, Karagwe and Buganda markets. In Buganda, coastal traders found a complex courtly life in which new technologies were welcomed, new ideas were vigorously debated and alliances with foreign powers were sought where they were deemed to further the strength of the kingdom. Aspects of coastal culture were thus gradually and cautiously adopted within the centralized political system of 19th century Buganda, in a way very similar to how aspects of Islamic culture were adopted in 11th century west-African kingdoms of Ghana, Gao and Kanem67.

While the activities of various itinerant Arab traders in Buganda has been documented elsewhere, especially during Kabaka Muteesa I's reign (r. 1856-1884) , it was the Swahili traders who made up the bulk of the settled merchant population and served the Kabaka in instituting several of his reforms that sought to transform Buganda into a Muslim kingdom. The most notable swahili men active in Buganda were Choli, Kibali, Idi and Songoro, the first three of whom came to Buganda in 186768in the caravan of the Arab trader Ali ibn Khamis al-Barwani, who returned to the coast after a short stay in the Kabaka’s capital but left his Swahili entourage at the request of the Kabaka. 69

Choli in particular was the most industrious of the group, when the explorer Henry Staney met him at Kabaka Muteesa's court in 1875, he wrote "there was present a native of zanzibar named Tori (Choli) whom I shortly discovered to be chief drummer, engineer and general jack-of-all trades for the Kabaka, from this clever, ingenious man I obtained the information that the Katekiro (Katikkiro) was the prime minister or the Kabaka’s deputy, and that the titles of the other chiefs were Chambarango (Kyambalango), Kangau, Mkwenda, Seke-bobo, Kitunzi, Sabaganzi, Kauta, Saruti70." and he added that Choli was "consulted frequently upon the form of ceremony to be adopted" on the arrival of foreigners such as Stanley and other coastal traders.71

Choli also carried out gun repairing, and soon became indispensable to the Kabaka who appointed him as one of his chiefs (*omunyenya in bulemezi province) and served as one of the army commanders in several of the Kabaka's campaigns including one against Bunyoro (which was the pre-eminent kingdom in the lakes region before Buganda's ascendance in the mid 18th century) Choli was granted a large estate by the Kabaka and lived lavishly near the King’s capital72.

Idi on the other hand was of Comorian origin, from the island of Ngazidja/grande comore ( Comorians are a coastal group whose city-states emerged alongside the Swahili's), he served as Muteesa's teacher and as a holy man, who interpreted various natural phenomena using quaranic sciences, he was appointed a commander in the Kabaka's army and was given a chiefly title as well, and he continued to serve under Muteesa's successors. Another swahili was Songoro (or Sungura) who served in Muteesa's fleet of Lake canoes at the lake port of Kageyi through which carravan goods were funneled into Buganda’s amrkets, and lastly was Muhammadi Kibali who served as the teacher of Muteesa, and from whom the Kabaka and his court learned Arabic and Swahili grammar and writing, as well as various forms of Islamic administration.73

It was these Swahili that Muteesa relied upon to implement several reforms in his kingdom, and by 1874 (just 7 years after al-Barwani had left) the Kabaka could converse fluently with foreign delegates at his court in Arabic and Kiswahili. Eager to further centralize his kingdom, he established Muslim schools and mosques, instituted Muslim festivals throughout the kingdom which he observed earnestly, he initiated contacts with foreign states, sending his ambassadors to the expansionist Ottoman-Egypt (whose influence had extended to southern Sudan), these envoys were fluent in Arabic corresponded with their peers in the same script, official communication across the kingdom (including royal letters) were conducted in both Kiswahili and Arabic, the former of which spread across the kingdom among most of the citizens.

The coastal merchants also sold hundreds of rifles to Muteesa in exchange for ivory, the Kabaka reportedly had 300 rifles, three cannon and lots of ammunition, "all obtained from zanzibari traders in exchange for ivory", by the 1880s, these guns were as many as 2,000, and by 1890, the figure had risen to 6,00074. The services of Swahili such as Choli and Songoro proved especially pertinent in this regard, as Henry Stanley had observed that among Muteesa's army of 150,000 (likely an exeggretated figure) were "arabs and wangwana (Swahili) guests who came with their guns to assist Mutesa".75 Although the use of guns and the assiatnce of the coastal riflemen in warfare was to mixed results for Buganda’s military exploits, as a number of records of their defeat against armies armed with lances and arrows reveals the limits of fire-arms.76

The most visible product of the cultural syncretism between Buganda and the Swahili beginning in Muteesa’s era was in clothing styles. Buganda had for long been a regional center in the production of finely made bark-cloth that was sold across the Lake kingdoms (Bunyoro, Nkore, Rwanda, Karagwe) and its influence in this textile tradition spread as far as the Nyawezi groups of central Tanzania.77The adoption of cotton-cloths during Muteesa’s reign complemented Buganda's textile tradition, and they were quickly adopted across the kingdom as more carravan trade greatly increased the circulation of cloth and by the 1880s, cotton was grown in Buganda78 and cotton cloths increased such that even some bakopi (peasants) were dressed in what one writer described as "arab or turkish costumes" of white gowns with dark-blue or black coats and fez hats79. as the Buganda elite adopted more elaborate fashions, as Henry Stanley wrote "I saw about a hundred chiefs who might be classed in the same scale as the men of Zanzibar and Oman, clad in as rich robes, and armed in the same fashion"80.

The adoption of this form of attire was mostly because of the Kabaka's commitment to transforming Buganda into a Muslim kingdom rather than as a replacement of bark-cloth since the latter's production continued well into the 20th century, and it retained its value as the preferred medium of taxation (and thus currency) that wasn’t be fully displaced until the early colonial era81. A similar but less pronounced cultural syncretism happened in the kingdom of Nkore which had been trading with the costal merchants since 1852 and by the 1870s was an important exchange market for the ivory and cloth trade although its rulers were less inclined to adopt Swahili customs than in Buganda.82 The Kabaka attempted to act as a conduit for coastal traders into the kingdom of Bunyoro but the latter’s ruler was more oriented towards the northern route to the Ottoman-egyptians, nevertheless, evidence of syncretism with Swahili culture among Uganda’s main kingdoms became more pronounced by the late 19th century.

original photo of “Mtesa, the Emperor of Uganda” and other chiefs taken by H.M.Stanley in 1875, they are all wearing swahili kanzus (white gowns) and some wearing fez hats

On the royal square on a feast day, men wearing white kanzus and some with coats and hats (early 20th century photo- oldeastafricapostcards)

Group of kings from the Uganda protectorate, standing with their prime-ministers and their chiefs. They are shown wearing kanzus, some with hats. 1912 photo (makerere university, oldeastafricapostcards)

Swahili cultural syncretism in the other lake kingdoms; Karagwe, Rusubi, Rwanda and Wanga

Karagwe:

The traders at Tabora and Ujiji whose northern routes passed through the Kingdom of Karagwe attimes assisted the latter’s rulers in administration especially since Karagwe was often vulnerable to incursions from its larger neighbors; Buganda and Rwanda. In 1855, king Rumanyika rose to power in Karagwe with the decisive help of the coastal traders who intervened on his behalf in a succession struggle. Similar form of assistance was offered in Karagwe's neighbor; the Rusubi kingdom, and the Swahili established the markets of Biharamulo in Rusubi and Kafuro in Karagwe, which extended to the South of Lake Victoria at the lake port of Kageyi, from which dhows were built by the Swahili trader Songoro in the 1870s to supplement the Kabaka’s fleet83. In 1894, King Kasusura's court in Rusubi was described as having a body-guard corps equipped with piston rifles, courtesans clad in kanzus, and the sovereign himself dressed in “Turkish” clothes and jackets.84

Rwanda:

In the kingdom of Rwanda (Nyiginya), coastal goods had been entering its markets through secondary exchange, it wasn’t until the 1850s, that a caravan with Arab and Swahili traders arrived at the court of Mwami (king) Rowgera (r. 1830-1853). coincidentally, a great drought struck the country at the time and the king’s diviners accused the caravan of having caused it and coastal merchants were barred formal access to the country, although their products still continued to flow into its markets, and two of Mwami Rwogera’s capitals became famous for their trade in glass beads, and many of the Rwanda elites drape themselves in swahili kanzus. The decision to close the country to coastal merchants was however largely influenced by the rise of Rumayika in Karagwe in 1855 who ascended with assistance from the coastal merchants, and the divination blaming a caravan for a drought was used as a pretext.85

Wanga

In western Kenya’s kingdom of Wanga, coastal traders established a foothold in its capital Mumias through the patronage of King Shiundi around 1857, and over the years grew their presence significantly such that Mumias became a regular trading town along the northern route. Swahili cultural syncretism with Wanga increased the enthronement of Shiundi’s successor Mumia, when explorers visited the kingdom in 1883, they found that Islam had become the religion of the royal family of Wanga, and by 1890, King Mumia was fluent in Swahili and the dress and language of the kingdom’s citizens adopted Swahili characteristics.

Just like in Buganda, the coastal traders also played a role in Wanga’s military with mixed results as well, during the later years of Shiundu's reign, the Wanga kingdom had control over many vassals the Jo-ugenya, a powerful neighbor that had over the decades defeated Wanga’s armies and forced the king to shift his capital way from Mumias to another town called Mwilala, and imposed a truce on the wanga that was favourable to them. Upon inheriting a kingdom which "had been dimished and considerably weakened by the Jo-Ungenya", Mumia enlisted the military aid of the coastal traders who, armed with a few rifles initially managed to turn back the Jo-Ugenya in several battles during the early 1880s, but as the latter changed their battle tactics, the coastal firepower couldn’t suffice and the Wanga were again forced into a truce86. By the 1890s, small but thriving Swahili merchant communities were established within the Wanga sphere of influence at Kitui and Machakos, although these never attained the prominence of Tabora or Ujiji since the northern caravan routes were not frequented.87

Eastern congo

Coastal merchants had reached eastern congo in the early 19th century, and in 1852, a caravan of Arab and Swahili crossed the continent having embarked at Bagamoyo in 1845, and following the central route through Ujiji, eastern Congo, and Angola to the port city of Benguela88. Ujiji served as a base for coastal traders into the eastern D.R.C following old, regional trade routes that brought ivory, copper and other commodities from the region. Despite the marked influence of the Swahili culture, few swahili merchants are mentioned among the caravan leaders and notable political figures of region’s politics in the mid-to-late 19th century.

One anonymous merchant is recorded to have travelled to the region in the 1840s, a German visitor in Kilwa was told by the governor of the city "of a Suahili (swahili) who had journeyed from Kiloa (kilwa) to the lake Niassa (Nyanza/Victoria), and thence to Loango on the western Coast of Africa" 89no doubt a reference to the above cross-continental carravan. Few other Swahili caravans are mentioned although several Oman-Arab figures such as Tippu tip (both paternal and maternal ancestors were recently arrived Arabs but mother was half-Luba), and dozens of his kinsmen are mentioned in the region, assisted by local administration.

Tippu tipu used a vast infrastructure of kinship networks that cut across ethnic and geographical boundaries to establish a lucrative ivory trade in the region. But his image as much a product of colonial exoticism and the role his position in the early colonial era, than a real portrait of his stature, and he was in many ways considered an archetype of coastal traders in the mainland.90 He established a short-lived state centered at Kasongo and in which swahili was used as the administrative and trade language and a number of Swahili manuscripts written in the region during the late 19th century have since been recovered.91

Portrait of a coastal family in eastern congo, 1896 (Royal Museum for Central Africa)

Conclusion: east africa and the global economy.

A more accurate examination of the economic history and cultural syncretism of 19th century Africa reveals the complexity of economic and social change which transcends the simplistic paradigms within which its often framed. The slave paradigm created In the ideological currents emanating from Europe during the era of imperial expansion and abolition had worked in tandem with more older racist literature to create stereotypes of Africa as a continent of slavery, and Africans as incapable of achieving "modernization", thus providing the rationale for colonial intervention and tropes to legitimize it in colonial literature. Post-colonial historians' reliance on inadequate conceptual tools and uncritical use of primary sources led them to attimes erroneously repeat these old paradigms which thus remained dominant.

But resent research across multiple east African societies of the late 19th century, has revealed the glaring flaws in these paradigms, from the semi-autonomous Swahili societies like Bagamoyo which prospered largely outside Omani overlordship, to the enterprising initiative of the Nyamwezi wage-laborers who opened up the coast to trade with the mainland (rather than the reverse), to the cultural syncretism of Buganda and the Swahili that was dictated by the former's own systems of adaptation rather than the latter's super-imposition.

19th century East Africa ushered itself into the global economy largely on its own terms, trading commodities that were marginal to its economies but greatly benefiting from its engagement in cultural exchanges which ultimately insulated it against some of the vagaries of the colonial era's aggressive form of globalization.

Read more about East african history on my Patreon

THANKS FOR SUPPORTING MY WRITING, in case you haven’t seen some of my posts in your email inbox, please check your “promotions tab” and click “accept for future messages”.

for critical analysis of such travelogues, see “The Dark Continent?: Images of Africa in European Narratives about the Congo” Frits Andersen and The Lost White Tribe by Michael Frederick Robinson

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 97-101)

Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels pg 113)

Indian Africa: Minorities of Indian-Pakistani Origin in Eastern Africa edited by Adam, Michel pg 103

War of Words, War of Stones by Jonathon Glassman pg 28-29)

The Island as Nexus by Jeremy Presholdt pg 321

The Swahili by Derek Nurse, Thomas Spear pg 83

The Island as Nexus by Jeremy Presholdt pg 326

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 96-97 )

The Workers of African Trade by P.Lovejoy pg 18)

The Island as Nexus: Zanzibar in the Nineteenth Century by jeremy presholdt pg 317-337)

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 72

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 128-132)

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 72, 82)

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 135, 141)

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 212-214

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg pg 148-151)

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 33 )

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 12-23

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 165

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 88-89)

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg pg 150-151)

A triangle: Spatial processes of urbanization and political power in 19th-century Tabora, Tanzania by Karin Pallaver

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 57-58)

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 150-151)

on ivory and elephant hunting in Buganda, Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard J. Reid pg 60-62

On the carravan trade and its effects in eastern africa, and Ufipa’s textile production; “Twilight of an Industry in East Africa” by Katharine Frederick pg 123-126, 174-176

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 89

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 6

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 153)

The structures of the slave trade in Central Africa in the 19th Century by F. Renault 1989, pg 146; Localisation and social composition of the East African slave trade, 1858–1873. by A. Sherrif ,pg 132–133, 142–144)

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 84, 90)

Slaves, spices, and ivory in Zanzibar by Abdul Sheriff 51-54

Slaves, spices, and ivory in Zanzibar by Abdul Sheriff pg 41-48

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg pg 154)

The Swahili by Derek Nurse, Thomas Spear

Horn and cresecnt by R. Pouwels pg 34-37, 72)

War of Words, War of Stones by Jonathon Glassman pg 31-39)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 277)

Buying Time: Debt and Mobility in the Western Indian Ocean by Thomas F. McDowpg 80-90)

Buying Time: Debt and Mobility in the Western Indian Ocean by Thomas F. McDowpg 90-100)

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 38-39)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 285)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 288)

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 18)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 275-276)

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 224

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg pg 55-56)

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 154)

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 154, The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 287),

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg 145)

Making Identity on the Swahili Coast By Steven Fabian pg 80-96

Making Identity on the Swahili Coast By Steven Fabian pg 50

Making Identity on the Swahili Coast By Steven Fabian pg 33-75)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 278)

Making Identity on the Swahili Coast By Steven Fabian pg 68)

Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar by A Sheriff pg 172

Twilight of an Industry in East Africa by Katharine Frederick pg pg 82

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 279)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 282)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 288)

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 49

Buying time: Debt and Mobility in the Western Indian Ocean by Thomas F. McDow pg 100-110

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 288)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 289)

the great lakes of east africa by Jean-Pierre Chrétien pg 483

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 291-292)

The Arab and Islamic Impact on Buganda during the Reign of Kabaka Mutesa by Oded Arye pg 218, 119)

see Ali’s biography in “sufis and scholars of the sea” Anne K. Bang pg 96, and “Horn and Crescent by Randall Pouwels” pg 119)

Through the Dark Continent by H.M. stanley pg 244)

Through the Dark Continent by H.M. stanley pg 265)

The Arab and Islamic Impact on Buganda during the Reign of Kabaka Mutesa by Oded Arye pg 220)

The Arab and Islamic Impact on Buganda during the Reign of Kabaka Mutesa by Oded Arye pg 220-223)

The Arab and Islamic Impact on Buganda during the Reign of Kabaka Mutesa by Oded Arye pg 225-227)

Through the Dark Continent by H.M. stanley pg 240)

The Arab and Islamic Impact on Buganda during the Reign of Kabaka Mutesa by Oded Arye pg 226)

Sokomoko Popular Culture in East Africa by Werner Graebner pg 48)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard J. Reid pg 28

The Arab and Islamic Impact on Buganda during the Reign of Kabaka Mutesa by Oded Arye pg 230)

Through the Dark Continent by H.M. stanley pg 270)

Political Power in Pre-Colonial Buganda by Richard J. Reid pg 74-75)

Research Paper, Issues 126-128 by University of Chicago, Department of Geography, 1970, pg 165, The Uganda Journal, Volumes 29-30 by Uganda Society, 1965 pg 189

Buying time: Debt and Mobility in the Western Indian Ocean by Thomas F. McDow

The great lakes of africa by Jean-Pierre Chrétien pg 195-198)

Antecedents to modern Rwanda by Jan Vansina pg 157)

Historical Studies and Social Change in Western Kenya pg 58-67)

The History of Islam in Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 291, Swahili Language and Society: Papers from the Workshop Held at the School of Oriental and African Studies in April 1982 pg 335

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 51

Carriers of culture by Stephen J. Rockel pg 51)

Debt and Mobility in the Western Indian Ocean pg 125-145

The arabic script in africa by Meikal Mumin pg 311-317).

The Swahili Culture is such an underrated and misunderstood history often times when anyone brings it up or talks about it slavery is all anyone reduces it to, which is not uncommon with anything African history related hell even so called Afrocentric scholars tend to be guilty of that too it can be frustrating but love this you always come through with great information dude.