Eurocentrism, Afrocentrism and the need to decolonize African history.

Moving beyond racist theories and fictitious pasts

The foundation of Eurocentrism and the Hamitic race theory

Western historiography of Africa is considered to have begun -in large part- after Napoleon's "discovery" of ancient Egypt in 1798. Prior to that, European scholars had little knowledge of ancient civilizations on the African continent as a whole; both north and sub-Saharan Africa (except for some flirtations with it in the writings of early explorers and Arab writers), and, having to acknowledge the impressive historical achievement of Egypt, Europeans were forced to reconcile this new discovery with their presumption of their own racial superiority by reclassifying the ancient Egyptians, whom they had previously been regarded as "black", as racially white.1

It was then that European scholars came up with several theories on how to bring African history into their racial-geographic understanding of world history which was at the time heavily influenced by scientific racism notably by the Gottingen school of History that subdivided the world into three major races; the Caucasoids in Europe, the Mongoloid in Asia and the Negroid in Africa. These classifications had no real basis scientifically but they were nevertheless relevant to rationalizing European expansionism, slavery, and the racial caste system in the Americas and seemed to complement the prevailing interpretations of the "curse of Ham" in Abrahamic religions (which initially associated Ham-ites with barbarism and slavery rather than civilization)

These categories not only entered mainstream discourse in various academic disciplines, they also became the very foundations of such; particularly anthropology and history, and were popularized in the philosophies of Friedrich Hegel and the writings of Francis Galton.

It was within this context that the Hamitic hypothesis arose. This elaborate racialist anthropological theory was refined in the early 20th century by British ethnologist Charles Seligman; it posits that "Hamites were European (ie; racially white) pastoralists, who were able to conquer indigenous agriculturalists because they were not only better armed (with iron weapons, which they are suggested to have introduced into sub-Saharan Africa), but also supposedly "quicker witted".

The Hamitic theory reversed the earlier view about ‘Ham’ (the son of Noah) and his progeny, from the archetypical barbarian to the harbinger of civilization in Africa, it incorporated the idea of white racial superiority and completely erased and denied the existence of "black African" states, inventions and cultural achievements instead attributing them to the influence of outsiders . This was the foundation of the Eurocentric interpretation of African history where African cultural accomplishments were ultimately tied with or derived from Western civilization —a vague categorization that includes all Mediterranean civilizations that Europeans appropriated as their own such as the ancient Sumerians, Phoenicians, and Egyptians.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

The foundations of Eurocentrism were laid by, among others, Georg Hegel from whom the modern arbitrary divisions of north and sub-Saharan Africa are attributed

Hegel claimed "Africa consists of three continents which are entirely separate from one another, and between which there is no contact whatsoever" he classifies Africa into "European Africa" which is northern Africa (from the Atlantic coast including Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia) he claims this region has always been subject to foreign influences, that "this is a country which merely shares the fortunes of great events enacted elsewhere, but which has no determinate character of its own", next in his classification is Egypt which he gives a triple classification as in Asia, Europe and its on its own. He writes that Egypt became the "center of a great and independent culture" and lastly “Africa proper” identified as sub-Saharan Africa which he claims "has no historical interest of its own and remains cut off from the rest of the world"2. It was on this foundation of deliberate erasure and dismissal that the themes in the modern of African history were constructed; scientific racism and social Darwinism.

Eurocentrism was thus not just a perverse underbelly in the interpretation and understanding of African history; it was the very basis of its creation; European anthropologists, philosophers, historians, and explorers formed these pre-conceived theories about what Africa was, how it came to be and who its people were even before stepping foot on the continent itself but were nevertheless regarded as authoritative figures from whom the authoritative and accurate interpretation of African history was to be sourced.

An outline of Eurocentrist founders of the modern studies of African history

It was within this racialist context that the so-called "founders" of the different branches of African historiography established their respective fields of study often based on blatantly racist ideologies that were at times criticized even by their contemporaries.

In the late 19th century in southern Nigeria, Leo Frobenius one of the earliest and influential historians of Yoruba society, claimed to have found evidence of the mythical city of Atlantis in Ile-ife, the cultural birthplace of the Yoruba claiming that that the Yoruba preserved the last remnants of a sea-faring Etruscan civilization, that one of the Yoruba deities - Olokun was the Greek god Poseidon, and that "the gloom of negrodom had overshadowed him" hence the Yoruba’s decent from glory to their then primitive state3 Frobenius would influence later Yoruba historians such as Saburi Biobaku4

the 13th century head depicting a royal from ife, it was seized by Frobenius from ile-ife

In the 1920s in Nubia, George Reisner -considered the father of Nubiology, wrote about Kerma (the first Nubian kingdom) that "the social mingling of the three races, the Egyptian, the Nubian and the Negro resulted in the production of offspring of mixed blood who don't inherit the mental qualities of the highest race, in this case the Egyptian"5 and "that a proportion of the offspring will perpetuate the qualities of the male parent and thus the highest race will not necessarily disappear"6 and when he encountered what was "unambiguously” Nubian material from the 25th dynasty, he still dismissed it and intentionally misattributed the artifacts and the entire dynasty's origin to the light-skinned Libyans beginning a “debate” on the origins of the Napatan Kingdom (which eventually conquered Egypt) solely based on a premise that the black Nubians couldn't have possibly established the dynasty themselves.7, Reisner inturn influenced later historians such as Anthony John Arkell's history of the sudan8

In the 1900s, in southern Africa at the ruins of Great Zimbabwe; archeologists Theodore Bent and Richard Hall —who are the pioneers in the studies of zimbabwe culture, believed that Africans could not have possibly built or even founded the city of Great Zimbabwe, Richard Hall, went on to destroy much of surface materials in the ruins claiming that the materials were recent bantu corruptions of the original white/Semitic builders, some of what was destroyed unfortunately included several constructions, materials and graves of royals and other notables that contained invaluable artifacts which later historians were deprived of in reconstructing the Zimbabwean past.9

the great enclosure at great zimbabwe

In Ethiopia, historian Conti Rossini claimed that the civilized elements of Ethiopia such as food production and state form of political organization were introduced by south Arabian groups who colonized the north horn of Africa region from the red sea.10 This speculative account of Ethiopian history remained unchallenged well into the 1950s

On the east African coast in the 1920s the British colonial administrators seeking to suppress Swahili identity and their cultural history concocted the fictional Persian colonial state called the “Zinj empire” centered at the city of Kilwa which they claimed was in control of the entire coast in the medieval era. These ideas were given academic merit by British historians Reginald Coupland and James Kirkman who were the first professional modern historians of the Swahili.

Reginald claimed that the entire coast was ruled by immigrant colonists who engaged in grand slave trading that affected the kingdoms of the interior and relegated the Swahili to slaves or wives of these Arab/Persian immigrants. Kirkman claimed that the Swahili ruins "belonged not to Africans but Arabs and Persians with some African blood" claiming Africans were incapable of such achievements.11

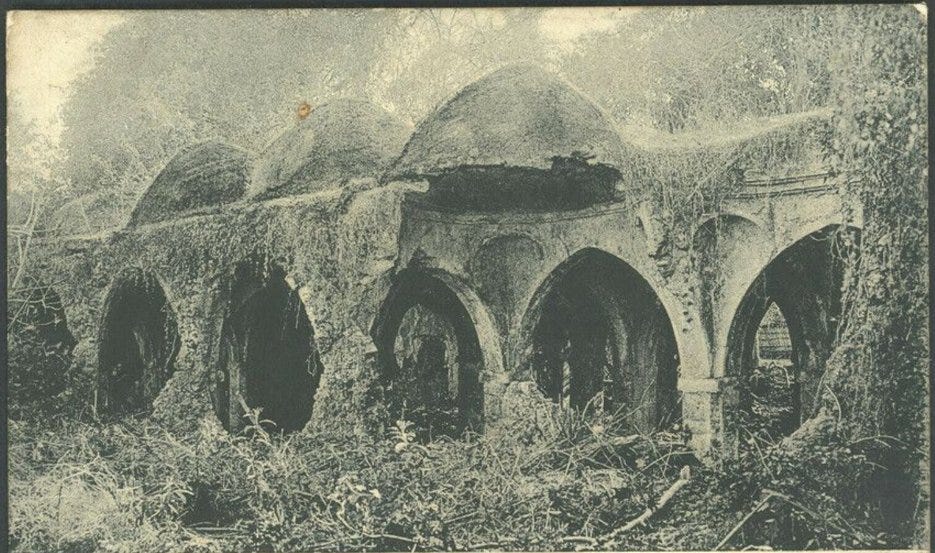

the ruined mosque of kilwa kisiwani in the 1910s before the bushes were cleared

Similar ideologies were present In the “western Sudan” where the (light-skinned) Berbers were assumed to have introduced state building, metallurgy, and domesticated crops to their (dark-skinned) southern neighbors such as the Mandinka. And in the great lakes region of eastern central Africa, where these so-called Hamitic groups (claimed to be the Tutsi or Hima) are said to have immigrated to, invaded, displaced, and conquered autochthonous groups, and supposedly introduced civilization, metallurgy, and statecraft to “negroid” groups who apparently had no knowledge of such.

These wildly inaccurate theories were given credibility by professional historians, archeologists, linguists, and anthropologists working in concert with the colonial governments to deny, erase, and deliberately misattribute African civilizations to the “white-adjacent” and fictitious Hamitic groups.

While critiques of Euro-centrist themes have been offered multiple times, especially by historians and archaeologists of Africa often taking up much of the introductions to their books, these critiques fall short of identifying the root of the problem with Eurocentrism which is that the premise of these Hamitic theories and Diffusionism theories was the underlying prejudice against non-western people rather than a genuine attempt at scientific inquiry in non-western history.

The “debate" on who built great Zimbabwe wasn't premised on a scientific comparison with the Middle Eastern cities (of its supposed builders), but on a racist conception that the Shona people (and other Bantu-speaking groups) couldn't build such structures. The misattribution of Swahili ruins to Arabs wasn't built on rigorous research between Arab and Swahili construction materials and styles, nor was it based on extensive studies of the Swahili language and its history, but instead on the prejudiced thinking that the Swahili couldn't have been the originators of their civilization and couldn’t be the builders of the ruins found along the east African coast. The same bad faith is behind the theories of West African metallurgy being introduced from Carthage, claims of African cereals being solely introduced from the middle east, and African cities existing only as foreign outposts.

The rise of Afrocentrism

As these historians dressed colonial racist interpretations of African history under the cloak of academic credibility, a counter-movement was growing among scholars of African descent In the Americas and the diaspora, one that in many ways mirrored the race-centered ideologies of colonial scholars but inversed their hypothetical center of world civilizations from “Western civilization” to Africa, specifically: Ancient Egypt, in large part drawn from the writings of 19th century Egyptologists. This movement later came to be known as Afrocentrism the foundations of which were laid in the racially-segregated US where history and race were politicized and considered central to people's identity and government policy.

While the US produced professional archaeologists like James Henry Breasted —who studied ancient Egypt and created the "great white race" hypothesis in which ancient Egyptians were supposedly the origins of the white race and all civilizations— there was also a growing crop of amateur scholars studying ancient Egypt that belonged to fraternal orders in the American white and black middle class. This resulted in the proliferation of masonic, theosophical, spiritualist, and esoteric writers in ancient Egypt which influenced the black-American middle class. The most notable of these lodges was the Prince Hall Grand Lodge in Boston which had major figures like William Monroe Trotter and Booker T. Washington.

The most influential of the masonic writers to early Afrocentrist scholars were the writings of Albert Churchward, an amateur English Egyptologist and adherent of freemasonry who claimed the secrets of freemasonry descended directly, unaltered from ancient Egyptian wisdom and customs. He advanced a very hyper-diffusionist Egypto-centric worldview with Egypt as the origin of all civilization, religion, laws of nature, code of laws and everything else; claiming that no other nation had improved upon them since. He claimed that Egyptians sent out colonies all over the world and that all other religions were mere imitations of Egyptian wisdom and that the belief systems of the Greeks, Romans, Jews only practiced pervasions of ancient Egyptian beliefs12

Despite Churchward’s racist beliefs about Africans (outside of Egypt), Afrocentrists nevertheless held onto his writings in search for historical sources of pride to counter the Eurocentrist’s prejudices because Egypt was the only African civilization that Europeans held in high regard. Having adopted Churchward’s theories, Afrocentrists then needed only to prove that all ancient Egyptians (or at least the majority) were racially Black.

Among those who adhered to Churchwards's hyperdiffusionist theories of ancient Egypt was the writer Molefi Asante; a black American who grew up In segregated Georgia. The central theme of Asante's works involves ascribing the origin of all civilizations to Africa -specifically Egypt. He writes that Egypt formed the basis of African cultures and its technologies and philosophies spread to the ancient Greeks and other civilizations, that Europeans then conspired to brainwash Africans of this past knowledge, and that Africans both home and in the diaspora should reclaim their glorious past13. Asante also cites two older influential Afrocentrist scholars like chancellor Williams and Cheick Diop

Cheick Diop is credited with the popularization of ancient Egypt as a genuine black African civilization; he claims that the emergence of all civilization and the biological origin of all humanity took place in Africa, that Egypt was a black civilization and that ancient Greece and the Europeans took everything of value from the Egyptian culture.14Diop emphasized that Africans should draw their intellectual, political and social inspiration from ancient Egypt, just as the Europeans did from Greco-Latin civilization, that African humanities should draw from pharaonic culture, ancient Egyptian and Meroitic writing should replace Latin and Greek and that Egyptian law should replace roman law. Diop also espoused race realism, claiming that Africa was culturally distinct from Eurasia. Much of Diop's work overwhelmingly quotes the writings of 19th century historians like Charles Seligman and Leo Frobenius15

Few Afrocentrists covered regions outside Egypt, one region of much attention was Meso-America and the supposed pre-Colombian landings of Africans in America based on a selective list of alleged similarities between Mesoamerican and Egyptian cosmologies, architecture and the Native American’s artistic sculptural self-depictions. From the Mayan pyramids to the presence of dark-skinned Native American groups, to the Olmec heads’ peculiar phenotype (which Europeans had, in their arbitrary constructions of race, reserved for “Black Africans”). A few books have been published by Afrocentrists like Ivan Sertima and Barry Fell, both of whom derived most of their theories from the writings of Leo Weiner's attempts at documenting Africans in pre-Columbian America16

A general critique of Afrocentrism is offered by Stephen Howe who observes that Afrocentrism is premised on three fallacies; unanimanism : belief that Africa was culturally homogenous, diffusionism : the belief that human phenomena have one common origin and primordialism : that present customs and identities are derived from an ancient past in unbroken continuity17.

Perhaps the most potent critique of Afrocentrism comes from the African historian and archeologist Augustin Holl to Cheick Diop; he says of Diop that “he behaved as If nothing new had occurred in African archeology”. This was indeed a valid critique because when Diop first published his "Nations nègres et culture" in 1954, the overtly racist interpretation of African history was mainstream as i have outlined, but Diop continued writing his theories as late the as 1974 in "The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality" when most of these racist themes had been replaced by more professional and much more academic interpretation of African history18

Between Eurocentrism and Afrocentrism: the rise of “"moderate” scholarship

Contemporaneous with the rise of Afrocentrism was the shift to a “moderate” reading of African history between the 60s and late 80s which coincided with the independence wave in Africa and the civil rights movements in the US that witnessed a rejection of the overtly racist Eurocentric themes of African history

While the overtly racial elements of eurocentric theories were being abandoned in the formative years of the post-colonial academic historiography of Africa which began in the 1950s and 60s , the diffusionist and Hamitic models continued to influence early historians, especially when it came to African metallurgy, complex state formation and growth, plant and animal domestication, the rise and fall of states, writing, adoption, use and innovation of new technologies, etc.

This moderate model of diffusionist and Hamitic theories, without the racial elements, can be observed in the theories of various historians like John Fage's work on ancient Ghana and west African empires in which he overstated the Berber influence on its rise, wealth and fall and the other early states of west africa19, Lanfranco Ricci's work on the formation of early Ethiopian states where he exaggerated the Sabean influence in pre-Aksumite era of the northern horn of africa20, James Kirkman who misinterpreted Swahili oral history and origin myths as a factual events21 , Neville Chittick on the Swahili coast who saw the Swahili as an African civilization with heavily Arabic and Persian influences in its foundation in his interpretation of the Shirazi myth22, in Nubia was William Y. Adams who characterizes the Nubian 25th dynasty as a classic example of a former barbarian people turning the tables on their former oppressors23 and many other historians focusing on west Africa and southern Africa

The relative influences of Eurocentrism and Afrocentrism on Africans and on the study of African history.

In terms of reviews, citations and circulation of their publications, Afrocentrist scholars are dwarfed by their Eurocentric and moderate peers, and they are often relegated to a footnote. In contrast, Eurocentrism wasn't (and isn't) just a minor perversion of an otherwise unbiased inquiry in the field of African historiography: it’s the very foundation of the field, and its adherents were the pioneers of African history and the self-appointed "founders" of their respective fields.

Eurocentric theories formed the core of the way African history is discussed and its eurocentric scholars that set the themes and topics of African history, from the fundamental eg determining if Ethiopian and Nubian historiography should be categorized as middle eastern, to the trivial, eg the tour guidebooks and museum guidebooks of African ruins and relics that were written during the colonial era and are still used today despite containing discredited theories on African history.

Worse still was Eurocentrism’s effects on the social institutions and psyche of African groups. History is political and has always been politicized whether as a source of cultural pride or as a way of “othering” groups of people to legitimize authority or justify atrocities.

For example in Rwanda, the Tutsi and Hutu were until colonization; a simple caste system in a complex relationship between the elites of several kingdoms vis-à-vis their subjects. This caste system was far from unique to Rwanda but was present in much of the eastern half of central Africa eg in the kingdoms of Nkore (in Uganda) and Karagwe (in Tanzania) and various groups in eastern Congo. During the precolonial period, some of these kingdoms were ruled by Tutsi elites and others by Hutu elites but this relationship was greatly transformed by colonial authorities into a racial designation by promoting and enforcing the Hamitic race myth, stating that “a Tutsi was a European under black skin”24, forcefully annexing independent Hutu-led kingdoms under the larger Tutsi-led Nyiginya kingdom, segregating schools by educating sons of Tutsi chiefs and leaders and feeding them on a steady diet of their supposed racial superiority over the Hutu, appointing them in colonial administration and physically creating the racial category by measuring the lengths of noses, the shape of skulls with calipers, separating relatives and siblings using arbitrary phenotypical differences and issuing “race” cards to maintain this segregation25 (a very divisive policy that was maintained well into the 1990s).

This process fueled animosity between these two groups sparking a series of mass murders primarily against the Tutsi first in 1959 and later –more infamously- in 1994 where 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutus were killed in less than three months in one of the world’s worst genocides based solely on the Hamitic theory as was best demonstrated in the dumping of bodies in the Kagera river that ultimately pours its waters into the Nile which the Interahamwe extremists claimed, was the fastest way to send the Hamites (meaning Tutsis) back to their homeland (Ethiopia and Egypt). The effects of this war spilled over into the D.R.C which sparked the first and second Congo war – one that involved over 7 African countries, claimed over 5 million lives in the most disastrous war since world war 2, and retarded the growth of the country for close to a decade.

The above example is just one of many conflicts created by the deliberate politicization of Eurocentrism in Africa, not including justifying the brutal apartheid system of white minority rule in South Africa based on the myth of empty land26, legitimizing the plunder and colonization of Zimbabwe and the later establishment of the segregated state of Rhodesia on false claims of a lost white builders of great Zimbabwe27, the effects of both still plague southern Africa today.

The case for Decolonisation of African history

Eurocentrism continues to plague mainstream discourses of African history attimes drowning African historians in vapid meta-commentary of discrediting the racist misconceptions about African history that they don't find the time to engage in the more rigorous work needed to highlight African history itself

The latter would require them to unearth new African archeological discoveries, translate and interpret old African documents, carefully examine the themes of African art, architectural styles, and social dynamics

As Toni Morison stated: "the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language and you spend twenty years proving that you do… somebody says you have no art, so you dredge that up. Somebody says you have no kingdoms, so you dredge that up"

Decolonisation requires nothing less than re-centering African history with the African societies that made it instead of bringing up African history only as meta-analytical critiques of Eurocentrism (the latter at times counter-intuitively legitimizes Eurocentrism as a valid theory of the African past)

Rather than dredging up art in response to Eurocentrists who claimed it didn't exist, the task for African historians is to dredge up African art to better understand the society that made it, rather than "digging up African kingdoms to idealize them so as to ridicule the cartoonish racist theories of eurocentrism that deny their existence, African kingdoms should be studied as a way of correcting colonial and post-colonial institutional deficiencies, instead of treating African achievements as trophies in the mundane tug of war against dismissive eurocentrist ideologues, African accomplishments should be seen as the stepping stone which African societies use to chart a clearer path for their progress by taking lessons from the past.

History is best useful when it helps those engaging it to grasp the present

Conclusion

Fortunately, many African historians are aware of the need to decolonize African history and some have taken on this task more assertively than others even without having to mention explicitly that they are ridding the field of Eurocentrism. Most notably in the study of Swahili history where historians such as John Sutton write that "the ruins at Kiowa, Songo Mnara and elsewhere on the coast and islands of Tanzania and Kenya, are therefore the relics of earlier Swahili settlements, not those of foreign immigrants or invaders ('arabs', 'shirazi' or whatever) as is commonly averred, although the mosques and tombs are by definition Islamic, they are not simple transplants from Arabian or the Persian gulf. their architectural style is one which developed locally, being distinctive in both its forms and its coral masonry techniques of the swahili coast".28

Other attempts at decolonizing history can also be seen in the study of West African history where historians such as Augustin Holl and Roderick Macintosh have re-oriented the origin and growth of the classic West African empires through their discoveries of the Tichitt neolithic's primacy on West African domestication, state building and architecture, and the unearthing of the city of Djenno Djenno which radically altered the understanding of pre-islamic trade and urbanism in west africa. Another region that's seen significant effort in decolonization is in the study of Zimbabwe cultural sites where archeologists like Shedrack Chirikure and Thomas Huffman have shifted the interpretations of the hundreds of Zimbabwe ruins away from mythical foreign builders to instead investigate their rightful origins among the shona groups.

Unfortunately, these attempts at decolonizing African history remain largely overshadowed by the legacy of their predecessors' Eurocentrism which still requires a concerted effort of decolonization from both the historians themselves and school systems in Africa and outside the continent. These educational systems perpetuate outdated products of Eurocentric thought into tour guide-books, in museums in modern journalism and political thought, all of whose perspectives on African history remains stuck in colonial thinking and require a complete overhaul in their approach to understanding the rich history of the continent.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Robin Law, The "Hamitic Hypothesis" in Indigenous West African Historical Thought

Teshale Tibebu, Hegel and the Third World: The Making of Eurocentrism in World History. Pg 172

Frieder Ludwig et al, European Traditions in the Study of Religion in Africa. Pg 189

Ancient Egypt in Africa, David O'Connor pg 86

George Andrew Reisner, Excavations at Kerma. pg 556

willeke wendrich, egyptian archaeology.

Steffen Wenig, Studien Zum Antiken Sudan: Akten Der 7. Internationalen Tagung Für Meroitische Forschungen Vom 14. Bis 19. September 1992 in Gosen/bei Berlin. Pg 6

Papers in African Prehistory jd fage pg 46

Pikirayi Innocent, The Zimbabwe Culture: Origins and Decline of Southern Zambezian States pg 14

Peter Robert shaw, A history of African archaeology. Pg 97

Allen, James De Vere, Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture and The Shungwaya Phenomenon pg 4-6

Stephen Howe, Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. Page 67

Stephen Howe, Page 232

Douglas Northrop, A Companion to World History

Stephen Howe, Page 164-174

Stephen Howe, Page 220

Stephen Howe, Page 232

Stephen Howe, page 167

Robin Law, The "Hamitic Hypothesis" in Indigenous West African Historical Thought

Rodolfo Fattovich, The northern Horn of Africa in the first millennium BCE: local traditions and external connections

Allen, James De Vere, Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture and The Shungwaya Phenomenon pg 4

Allen, James De Vere, Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture and The Shungwaya Phenomenon pg 9

David O'Connor, Ancient Egypt in Africa. Page 161

Alain Destexhe, Rwanda and Genocide in the Twentieth Centur, pg 39

Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda pg 76-101

Shula Marks, “South Africa: 'The Myth of the Empty Land

Scientific Racism in Modern South Africa. By Saul Dubow pg 87

G sutton; kilwa A history pg 118

Many thanks, dear Isaac Samuel. Your article is well-written, clear, concise and empowering. Humanity needs to know the truth, particularly for Africans and those living in the diaspora, to free themselves from the bondage of Eurocentrism, imperialism, and inferiority complex. I came across a recently published book entitled: Beyond Eurocentrism: The African Origins of Mathematics and Writing. In it, the author discusses the African origins of mathematics and writing. A must-have treatise for all of us. Thank you very much.

Kwaku

This is one of the best cases for decolonization I’ve read so far.