Hausa urban architecture: construction and design in a cosmopolitan African society

On the question of Decline or Metamorphosis of African vernacular architecture

Architecture represents an essential emblem of a distinctive social system and set of cultural values, combining a diverse range of cultural aesthetics, spatial concepts that govern the interactions of people and their environment, as well as the society's cosmologies. The architecture of Hausa compound, which is the basic dwelling unit of an extended family, is an ordered hierarchy of spaces which adhere to an implicit cultural paradigm. Houses weren't simply lodging places sheltered by a roof and confined within walls, but were laid out in an elaborate spatial order that included courtyards, gardens, compounds, entrances and open spaces where both public and private festivities took place, where craftworks were carried out and religious rites were held —the physical buildings were only the most visible component of the wider system.

Hausa architecture participated in a broader cultural agenda of Hausa society, serving as a mechanism and symbol for communicating concepts of power, religion and visual arts, with royals and the wealthiest urban residents constructing extensive compounds with imposing edifices and intricately decorated façades. They utilized a wide range of architectural features and designs in Hausa construction including vaulting, double-story buildings, large domes and spacious interiors and entrances, their compounds contained multiple buildings housing dozens of their extended families as well as servants and craftsmen; and the ostentatiousness of each compound served as an easily recognizable gauge for its owners' social status. Hausa masons and architects used locally occurring building materials especially palm-wood and rammed earth to create some of the grandest architectural feats attested in the medium, constructing buildings that served both a functional and monumental purpose, and that were best suited for the alternating humid and dry climate of the region. As a cosmopolitan society, the Hausa masons also tapped into the broader range of architectural styles and techniques of construction across west Africa while retaining a distinctively original style.

This article provides an overview of Hausa architecture including the profession of construction in the Hausa city-states, the most commonly used building materials, as well as a select look at a number of Hausa buildings and their architectural features.

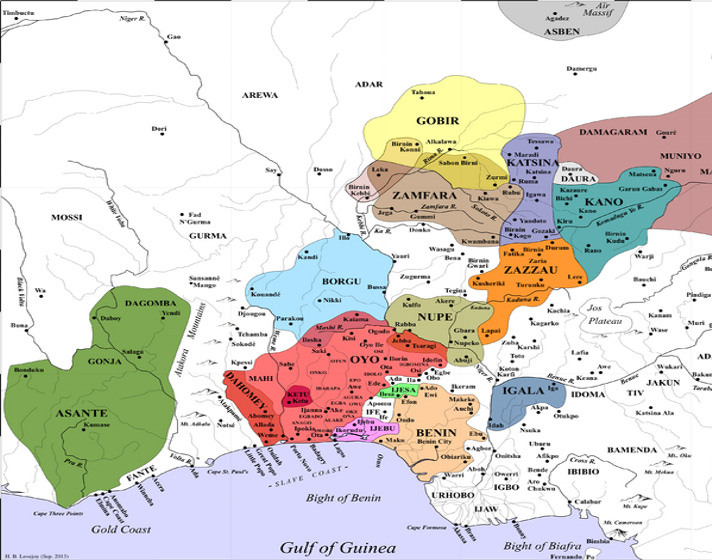

Map of the hausa city-states and their neighbors in the 18th century

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The builders: Hausa architects and masons.

The stable urban environment that followed the rise of the Hausa cities by the mid 2nd millennium enabled the emergence of a wealthy elite class which employed a professional building class of artisans and masons. In most Hausa cities, this building class was organized under the Sarkin Magina, (chief of the builders) responsible for maintaining the standard of workmanship controlling the recruitment of officials and retainers into the building profession conscripting labour for public works and maintaining the palaces and other public buildings1

It was the Sarkin Magina’s guild of craftsmen and master builders (gwanaye) who constructed the elite houses, mosques and palaces that the Hausa cities are famous for2. A typical Hausa mason used knowledge acquired after a 10-year apprenticeship course under a masterbuilder, as well as their own personal skills acquired through experience to know the highest quality timber and mortar, standard measurements of roofs, foundations and walls as well as the construction of arches, plastering and decorating plus the most useful basic instruments of measurement.3

In 1823, the explorer Hugh Clapperton described the construction of a mosque in the city of Sokoto by a Hausa architect from Zaria and his team of craftsmen who were at the time building a flat-roofed hypostyle-mosque, some of whom were decorating, others roofing while the architect supervised them, the architect told Clapperton that his father been to Egypt and acquired formal training in architecture and left him with his papers, he also asked Clapperton for a Günter's scale4.

Another architect active at the time was the famous Malam Mukhaila Dugura who was born in Katsina in 1784, he is famous for building a number of palaces in several Hausa cities as well as the Zaria Friday mosque in 1840; a domed mosque with several arches spanning over 8 meters and arguably the most iconic pieces of Hausa architecture.5 Hausa masons were a fairly prestigious profession and each city often had several hundred at a time, their diverse skillset from building to roofing to decorating allowed them to claim fairly high wages and reside in some of the most spacious homes in the cities at times rivaling those of their clients.6

The building materials: brick, mortar and timber in Hausa construction

sundried mud-bricks are arguably the most ubiquitous construction material across west Africa (often supplemented by dry -stone and fired-brick), the earliest sundried mud-bricks (both cylindrical and “loaf-shaped” rectangular bricks) are attested in the second half of the first millennium at the city of Djenne jenno, while fired bricks were used for reinforcement possibly as early as the late 1st millennium AD, and not long after their increased use, the erection of rectilinear buildings appears around the 9th-10th century.7 Rectangular sundried mud-bricks and fired-bricks also appear around the 8th and 9th century at the city of Gao in Mali as well as large rectilinear building complexes8, as well in the cities of Tegdaoust and Kumbi saleh where many similar buildings have been found9, fired bricks and mud-bricks also appear in construction of elite houses in several cities in the region of Kanem-Bornu near lake chad by the 11th century10, however, the technology of making the type of conical/egg-shaped Hausa mud-bricks (tubali) is purported to have originated from the Hausa cities themselves into the lake chad region; given the extensive contacts the Hausa city-states had with these regions.11

The exact size of tubali varies from city to city, they are made by brickmakers after wetting and trampling earth until its malleable, the lump of earth is then molded to form the tubali and left to dry in the sun for several days. Specially selected types of clay is preferred for making such bricks, eg clay with a high gravel content called burgi (rammed earth), while swamp mud (tabo) is primarily used in plastering, as well as earth with a high clay content (kasa) that is used for mortar and plaster, with the latter often containing red pigmentation that gives Hausa houses their iconic reddish-brown finishing. The other primary construction material is deleb palm-wood (azara) whose rough, fibrous surface creates a good bonding surface and provides a lightweight timber relative to its length that enables the construction of flat roofs and is ant resistant.12

Profile of an un-plastered Hausa construction showing the conical mudbricks, azara timber and rammed earth

tubali mud-bricks in the 14th century city-wall of Garoumélé, Niger

The constructions: a profile of Hausa walls including household enclosures and city walls

The most distinctive feature of Hausa cities were their extensive system of walled fortifications that served both military and symbolic functions, enclosing both agricultural and residential land that comprised the city (Birni). The birni sits at the apex of the hierarchical notions of settlement in Hausa culture, such cities were often surrounded by smaller towns (Gari) and villages (Kauaye) which were also enclosed within high perimeter walls.13

Hausa house walls are made of rectilinear courses of tubali, with each brick laid between thick mud-mortar, these walls are constructed with about 5 to 6 pieces of tubalis at the bottom and grow thinner to the top with 2 tubalis inorder to ensure strength and stability by having the walls taper up rather than rise with the same width to the roof14. City walls are substantial earthen ramparts on the inside that is several feet thick at the base, that are faced with mudbrick on the exterior, with large wooden gates punctuating the length of the wall, the earliest of such walls were built around the city of Kano in the 11th century15, and later in the cities of Katsina, Zaria16, Daura, Gobir by the 15th century. These city walls were often reinforced with stone and a few of them were completely built with stone such as the city walls of surame, the scale of these walled fortifications was extensive, the city-state of kano alone having more than 40 towns and villages within a 48 mile radius, all of which were enclosed in high walls.17 Most of these walls have since the early 20th century, been allowed to deteriorate as the cities expanded outside their original enclosed core.

sections of the kano walls on the exterior and interior

section of the Katsina walls

section of the Zaria walls

Gates of Bauchi

Windows, Doors and other architectural features

The windows (taga) of Hausa houses were typically small (almost slit-like) and were located high on the exterior walls of the household complex, with wooden shutters to allow daylight in and a controlled draught of air, this was ideal for both the humid climate; permitting maximum airflow through the building in the wet season while allowing for the thick walls to provide thermal insulation through the dry season as well as relying on the highly reflective surfaces to regulate the heat.18 External doorways in Hausa buildings were closed using wooden or iron doors (kofa) which rotated a pivot while inner doorways which were often covered with curtains. The use of lintels, beams, brackets and corbels were common in the design of the doorway.

profile of houses in Zaria showing the positioning of windows and doors

The household complex: Hausa Compounds and Palaces

The Hausa compound; the basic housing unit, is an ordered hierarchy of spaces which adhere to an implicit cultural paradigm derived from both traditional Hausa and Islamic customs, a traditional Hausa residence is conceptually subdivided into three parts, an inner core (private area), a central core (semi-private area), and outer core (public areas). Upon entering the main door/gate (kofa), visitors access the house through the entrance (zaure) this is where most of the public is restricted, while more familiar visitors are ushered into the first hall (shigfa) that is separated from the zaure by a forecourt (kofar gida), this in turn leads to the private inner court (cikin gida) that is restricted to close relatives and is the primary residential unit of the household containing kitchens, sleeping places, and quarters for extended family.19

Layout of a typical Hausa compound, the compound of the Mallawa Family in Zaria

Hausa Palaces

In its basic spatial layout, the Hausa palace is an extended form of the Hausa compound, retaining the main features such as the zaure, the kofan gida and the cikin gida but constructing them on a much larger scale. The palatial construction is comprised of a complex of buildings and open spaces partially open to the public while the residential quarters and inner quarters house the royal family and the king's wives. The vaulted spaces of the interior of a typical Hausa palace employ combinations of azara timber that is cantilevered at angles from the walls to create arches to support the roof, allowing for open spaces spanning over 8m in length and tall roofs upto 9m high, the interior walls are often richly decorated with a range of Hausa and arabesque motiffs.20

Layout of the Kano and Zaria Palaces

Arguably the oldest palace still in use is the Gidan rumfa in Kano built in the late 15th century by Muhammad Rumfa, the entire complex covers around 33 acres with the built up section measuring 540m x 280m, the palatial residence houses the king's chambers, the meeting place of the kano council, the royal stables, the residential quarters for the king's family and wives, as well as quarters for craftsmen and guards.21 Similar palace were erected in the Hausa cities of Katsina, Zaria, Daura, Dutse ; the erection of these spacious buildings with audience chambers and council chambers within the palace, reveal an imposing type of construction employed by Hausa architects and their patrons that could accommodate large spans of open space to compliment their monumental character.22

sections of the 15th century Gidan Rumfa in Kano

sections of the Katsina Palace

sections of the Daura Palace

A unique architectural feat in west-African mud-brick construction: The Hausa Vault and Dome

Domes are a prominent feature of Hausa architecture, Hausa master masons devised a variety of structurally appropriate arch configurations to maximize the free-span of rectilinear buildings, and despite the structural limitations of the construction materials, they attained incredible feats of architecture with the largest free-spaning areas under a domed roof measuring 8.2mx8.65mx6.75m in Kafin Madaki (built in 1861), and another in the Soron inglia (built in 1935) inside the kano palace, which spanned 7.5mx8.25mx9m23. The origin of the Hausa dome can be traced to the traditional houses of the Hausa which often contained domed ceilings under thatched roofs, these domes were built of mud mixed with straw and were constructed without centering, beginning from the top of the building’s round walls and rising in layers to the apex.24 As the architect Labelle Prussin writes; “The Hausa vault and the Hausa dome are based on a structural principle completely different form the north African, Roman-derived stone domes, On the other hand the 'Hausa' Domes incorporate, in nascent form, the same structural principles that govern reinforced concrete design".25

The construction of Hausa arches (Kafa) is achieved by cantilevering successive sets of azara from opposite ends of the room to generate the basic form of the arch, as well as to support the subsequent layers of azara and for structural stability, the framework of the azara is bounded together with cord and the basic form of the arch is generated by the angle of the slope of the azara, the entire feature is then finished by daubing the framework with swamp mud, after the first kafi is imbedded vertically in the walls, successive kafi are laid at diminishing inclines with various lengths, the first around of these kafi usually measuring atleast 0.5m, the second 0.75m, the third 1m and the forth is 1.5m. The master mason often builds both arches simultaneously from opposing walls until they abut each other and another layer of azara is then superimposed on the abutting kafi to reinforce them and ensure the arch is structurally sound. The arches are strong enough to support an upper storey which is found in some of the wealthy compounds and whose top floor construction utilized the same building principals as ground floor but with lighter materials26. The dome (tulluwa) itself rests on these intersecting half arches, and is completed with mud mortar, which is inturn covered in a indigenous cement known as laso, made from dyepit residue, indigo liquid, ash, and a viscous vegetal substance. This cement remains impervious to rain for about 5 years after which it is reapplied.27

profile of double-story hausa building and cross-section of a hausa arch revealing the placement of the azari

Vaulted ceiling of the Kano palace

Vaulted ceiling inside a Hausa home

A double-storey house in Kano

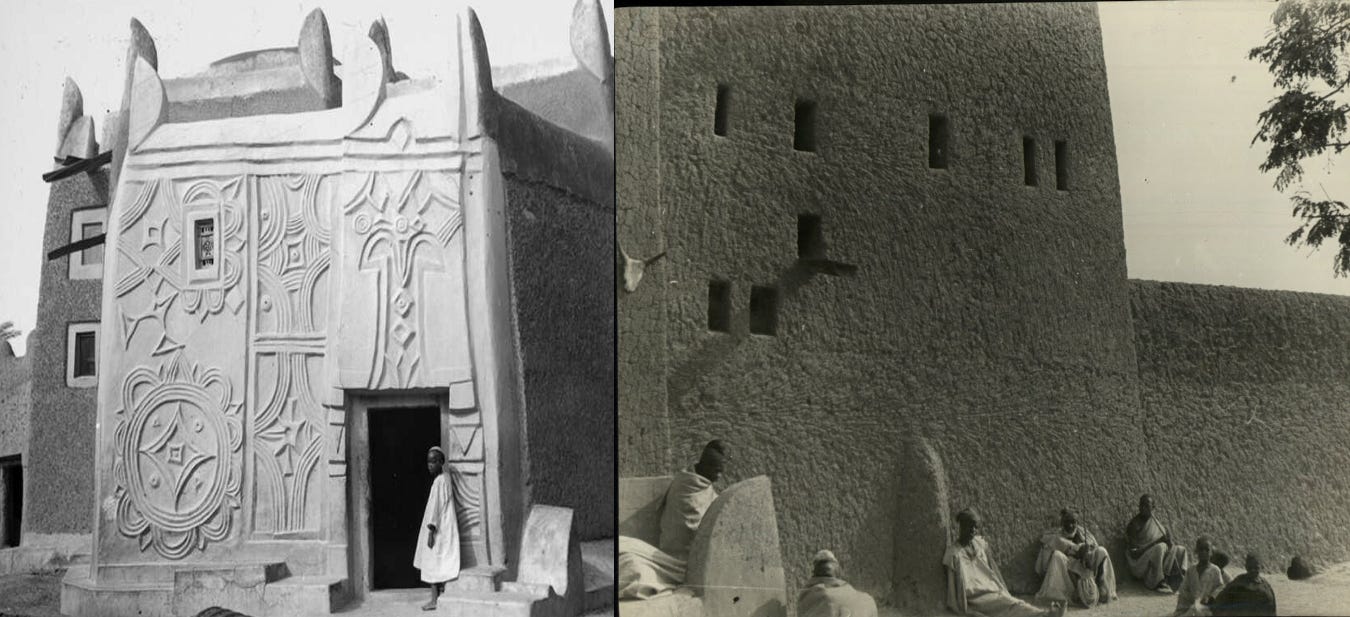

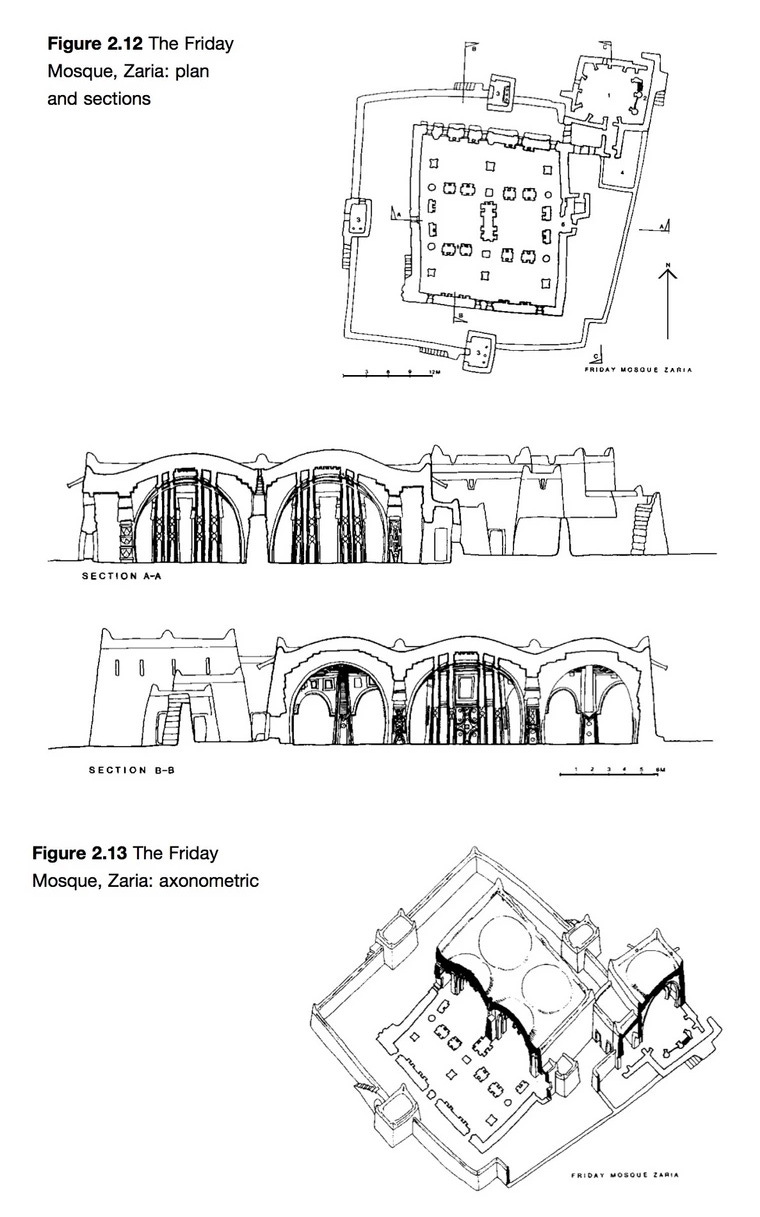

The Hausa domes and vaults in the Friday mosque at Zaria

The Zaria mosque was described by architectural historian Zbigniew Dmochowski as “the most notable achievement of Nigerian ecclesiastic architecture” writing that "its spatial composition was most impressive and imaginative, the structural skill of its designer has never been equaled in any other mosque in the country, the architect applied practically every device ever used in northern Nigeria, enriched them with a number of his own creations and combined them in a serene logical whole, through a complex web of stanchions, arches, ribs and domes"28 the mosque's domed roof which formed six bays is supported by 16 massive piers and several arches allowing an open space spanning over 1500 sqm; filling the ceiling coffers were parallel rows of tightly positioned timbers and the interior was enriched with decorative plaster moldings and geometric incised elements.29

The mosque is accessed through the zaure at the entrance of the perimeter wall courtyard of the complex, adjacent to this is the domed sharia court used by other high officials, the arches in the interior rise almost directly from the floor and take on a semi circular form, these arches are richly decorated with geometric relief motifs from most of the Hausa canon. The mosque relies on its exterior apertures for its source of natural light and its shimmering floor resonates with shadows and a myriad of reflections allowing the interior to be moderately lit.30 The mosque’s exterior has since been covered under a modern mosque but much of the interior remains intact.

the Zaria mosque in the 1920s showing the ribbed vaulting and Domed exterior

Hausa house Façade and Decorations

Jutting out into the sky and visible above the Hausa roofs cape are the roof pinnacles zankwaye, these may serve a functional purpose by adding weight to certain parts of the building most vulnerable to torrential rains or easing the task of resurfacing the roof, however, the primarily function seems to have been decorative and symbolic as its featured on Hausa clothing designs, hats, regalia, ceiling patterns; hausa pinnacles have come to be accepted as a mark of aesthetics in Hausa traditional façade.31

Another feature are the roof eaves, (Indororo) which extend out from the palm-wood structure inside the roof. these Long and projected roof eaves and spouts serve to drain rain from the roof and prevent the water from soaking or weighing it down.

Aerial view of the city of kano with the iconic hausa pinnacles projecting out of its flat-roofed buildings as well as roof eaves for draining out rain-water

Hausa house in Kano with several roof pinnacles and drains

types of Hausa roof pinnacles

In Hausa traditional architectural decoration, the wall engravings are designed by traditional builders, these used a range of abstract and decorative motifs depending on their experience that include Hausa motifs and relief patterns as well as arabesque motifs32, specialized artisans and highly skilled hand engravers who can draw out minimal outlines directly on the wall surface. The most common motifs used in Hausa designs are; the Dagi knot, the staff of office and the sword, and several abstract motifs, initially, these motifs would be larger and used moderately, but in the 20th century, new builders used smaller motifs that interlaced with each other such as the entrance to the Zaria palace, the Bauchi Palace and the Dutse palace.33

Intricate Hausa geometric patterns on the palace walls at Dutse

hausa motifs on the palace walls at Bauchi

The decorated façades of houses in the cities of Katsina and Kano

Conclusion: African architecture between the "traditional" and the "modern".

Hausa architecture is a product of autochthonous styles of construction and building materials, as well as the cosmopolitan character of Hausa city-states which incorporated a number of foreign styles into the local milieu in a process dictated by a balance between the prosperity of the local economy, the availability of building materials (both local and imported) as well as the level of craftsmanship in the society, it's because of a combination of the latter that new ("western") forms of construction and design have been quickly adopted by Hausa architects and masons, and in the eyes of most observers, has led to the decline in the "traditional" form of Hausa construction.

While academic discourse of African "vernacular" architecture stands at a cross-roads between the African people's perceptions of the feasibility of living in "traditional" houses and the need to conserve these unique architectural styles, the incorporation of "modern" construction styles should not be seen through a dichotomous lens that’s split between preserving a dying tradition and a wholesale shift into modern architecture, but rather as part of a longer synthesis of incorporating foreign styles into local building styles; a skill which had already been mastered by Hausa masons over the centuries. The increasing interest in using modern building materials to make traditional Hausa constructions (as well as other styles of African architecture) should be a welcome process not just for the cultural continuity but also as part of the movement towards sustainable architecture; creating buildings that are durable, affordable and culturally enriching.34

the Hikma complex in Niger, an example of modern Hausa architecture

for more on African history including the architecture of the Hausa, please subscribe to my Patreon account

Hausa Urban Art and Its Social Background by Friedrich W. Schwerdtfeger pg 109)

Hausa Urban Art and Its Social Background by Friedrich W. Schwerdtfeger pg 104,107-108)

Maximizing mud by Susan B. Aradeon pg 226

Narrative of Travels and Discoveries in Northern and Central Africa in the years 1822, 1823, and 1824, by Major Denham, Captain Clapperton pg 103

Hausa Urban Art and Its Social Background by Friedrich W. Schwerdtfeger pg 111)

Hausa Urban Art and Its Social Background by Friedrich W. Schwerdtfeger pg 107-116

Excavations at Jenné-Jeno, Hambarketolo, and Kaniana by Susan Keech McIntosh. pg 18, 36,50, 215)

Discovery of the Earliest Royal Palace in Gao and Its Implications for the History of West Africa by S Takezawa

Etude archéologique d'un secteur d'habitat à Koumbi Saleh (Mauritanie) by Sophie Berthier

Early Kanem-Borno fired brick élite locations in Kanem, Chad by C Magnavita

Conquest and Construction By Mark DeLancey pg 23-24

Maximizing mud by Susan B. Aradeon pg 208-209)

Power and permanence in precolonial Africa by A Haour pg 553-555)

The practice of Hausa traditional architecture by GK Umar pg 8

African Civilizations by Graham Connah pg 125)

Hausa Urban Art and Its Social Background by Friedrich W. Schwerdtfeger pg 17-19)

African Civilizations by Graham Connah pg 125 pg 125)

Hausa Architecture by Cliff Moughtin pg 120

an exegesis of the Hausa and Fulani models by by AI Kahera pg 66)

an exegesis of the Hausa and Fulani models by by AI Kahera pg 70-72)

(Islam, Gender, and Slavery in West Africa. Circa 1500 by HJ Nast, pg 55)

an exegesis of the Hausa and Fulani models by by AI Kahera pg 70-72)

Maximizing mud by Susan B. Aradeon pg 206)

butabu By James Morris, Suzanne Preston Blier pg 209)

an exegesis of the Hausa and Fulani models by by AI Kahera pg74)

A Study on the Building Materials and Construction Technology of Traditional Hausa Architecture in Nigeria by J. Zhang, Z. Yusuf

Maximizing mud by Susan B. Aradeon pg 210 214)

An Introduction to Nigerian Traditional Architecture, Volume 1 Zbigniew R. Dmochowski pg 2-16

butabu By James Morris, Suzanne Preston Blier pg 208)

an exegesis of the Hausa and Fulani models by by AI Kahera pg 85-88)

an exegesis of the Hausa and Fulani models by by AI Kahera pg 59-60)

Hausa Urban Art and Its Social Background by Friedrich W. Schwerdtfeger pg 230-233, 251-255)

Cultural Symbolism in the Traditional Hausa architecture of Northern Nigeria pg 33-34)

for more on this debate see: “Contested Legacies: Vernacular Architecture Between Sustainability and the Exotic by Neveen Hamza

Excellent! The quality of research and clarity of communication is just ... excellent!