Historical links between Africa and Armenia (ca. 600-1900)

Travelers, merchants and scholars from Nubia, Ethiopia and Armenia who visited the southern Caucasus and North-eastern Africa.

Africans travelled across most parts of the Old world prior to the modern era, from the cities of Islamic Spain to the Imperial courts of China, and many places between. Among the lesser-known regions visited by Africans was the southern Caucasus, a region between the Caspian and Black sea that was under the control of various empires and kingdoms.

In the early centuries of the common era, this region was controlled by the kingdom of Armenia, which was itself part of several ‘Eastern’ Christian societies that extended to the Nubian kingdoms of the Nile valley and the Aksumite kingdom in the Horn of Africa. Pilgrims, scholars and traders travelled across this region, fostering cultural exchanges that can be gleaned from the influences of the Ethiopic script in the Armenian script as well as the influences of Armenian art in Ethiopian art.

The kingdom of Armenia was later gradually subsumed under the Roman (Byzantine) and Persian (Sassanian) empires by the 5th century, remaining under the control of suceeding Islamic empires, with the exception of the independent kingdoms of Bagratuni (885-1045) and Cilicia (1198-1375). Armenian speakers would thereafter constitute an influencial community in the eastern Mediterranean, where they would interact with their African co-religionists and eventually establish cultural ties that led to Africans visiting the southern Caucasus and Armenians visiting and settling in Ethiopia.

This article explores the history of cultural exchanges between the southern Caucasus and North-east Africa focusing on the historical links between Armenia, and the kingdoms of Makuria and Ethiopia.

Map showing the kingdoms of Armenia, Makuria and Ethiopia as well as the probable route taken by Ewostatewos from Ethiopia to Armenia.

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early Contacts between the Nubian, Ethiopian and Armenian diasporas the eastern Mediterranean.

Diasporic communities of Africans from the Nubian kingdoms and Aksum, were first established in Egypt which was home to many important sites of Christian asceticism since antiquity, and from here spread out into the eastern Mediterranean and eventually into the southern Caucasus.

One of the earliest mentions of 'Ethiopians' in Egypt (an ethnonym that was at the time used for both Nubians and Aksumites) is first made in a 7th century text by the Armenian scholar Anania Shirakatsi, who mentions that an 'Ethiopian' named Abdiē contributed to the joint project of the Alexandrian scholar Aeas in establishing the 532-year cycle. Anania also mentions Ethiopians (presumably Aksumites) in other works concerned with the calendar as well as providing an accurate Armenian transcription of Gǝʿǝz month names which he faithfully reproduced from his Ethiopian informants. This remarkably early encounter between Armenian and Aksumite scholars indicates that the links between the two regions were much older than the few available sources can reveal.1

Both Aksum/Ethiopia and Nubia had a long history of connections with the 'Holy lands' where Nubian pilgrims are identified as early as the 8th century. One of the earliest mentions of African Christians in the eastern Mediterranean comes from the Syriac patriarch Michael Rabo (r. 1166–99) who suggests the presence of Nubians and Ethiopians in Syria, Palestine, Armenia, and Egypt during the late 1120s. Descriptions of the diasporic community of both Nubians and Ethiopians reach their peak during the 13th to 15th century, where they are identified by many Latin (crusader) accounts who mention an 'infinite multitude' of these African Christians in the Holy Sepulchre (Jerusalem), Nazareth, Bethlehem, as well as in Cyprus, Lebanon and Syria.2

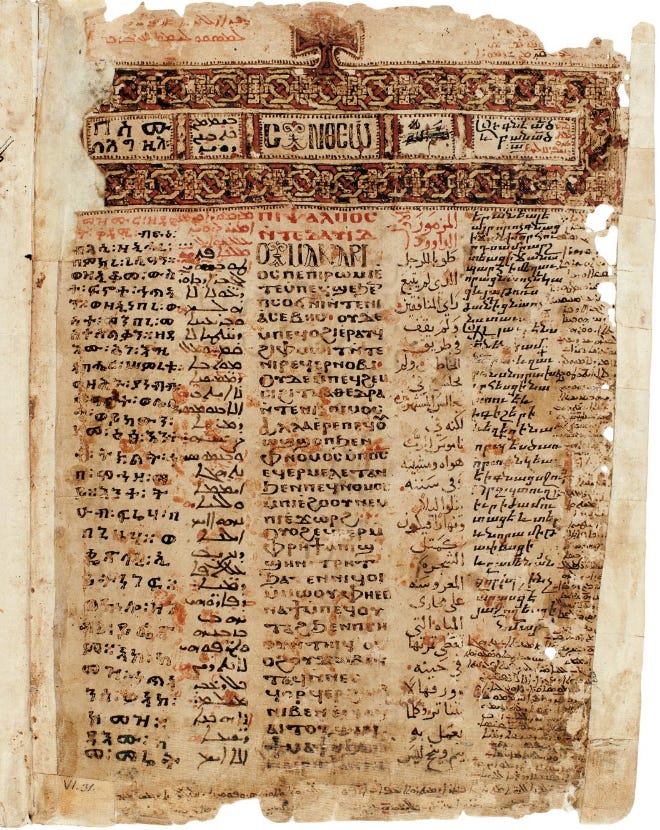

copy of a Psalter written in multiple scripts, 12th-14th century, monastery of saint macarius, wadi al-Natrun, Egypt3. Beginning with ethiopic/ge’ez on the extreme left column, followed by Syriac, Coptic in the center, Arabic on the right and ending with Armenian.

These polygot texts facilitated comparative study of the bible by different groups as well as common reading in the liturgy, since Nubians used Greek and Coptic (alongside Old Nubian) in liturgical contexts, such texts attest to the presence of Ethiopians, Nubians and Armenians in Egyptian monasteries.

Nubians and Ethiopians in the Cilician kingdom of Armenia.

It was during their stay in the 'Holy lands' that the Nubian and Ethiopians interacted with their Armenian peers as part of the shifting alliances and conflicts over the control of holy sites and places of worship between the various Christian factions, as well as the intellectual and cultural exchanges which prefigured such interactions.

There is some fragmentary evidence of Nubians in Cilician Armenia during the 13th century. This can be gleaned from a statement by the Armenian prince Hayton of Corycus, who, whilst in France, wrote in his Crusade treatise that Armenians could be used as messengers between the Latin Papacy and the Nubians. It may be presumed that some Nubians travelled to Armenia as messengers at various times in order for Hayton, who was also a prince of Armenia, to advertise seemingly strong communication networks between Nubia and Armenia. There is afterall, evidence of a Nubian king travelling with his entourage to the Byzantine capital Constantinople in 1203 from Jerusalem, likely using an overland route through Armenia.4

Stronger evidence for Africans in Armenia however, comes from Ethiopia. In the early 14th century, the Ethiopian scholar named Ewosṭatewos created a powerful, yet dissenting, movement in northern Ethiopia about the observance of the Christian and Jewish sabbath, which eventually led to his banishment. In 1337-8, he left Ethiopia with some of his followers, beginning a long journey that led them through the kingdom of Makuria (in Sudan), Egypt, Palestine, and Cyprus before he finally arrived in Cilician Armenia.5

Ewostatewos had left Ethiopia with a significant entourage of other monks and scholars, who briefly assisted the king of Makuria in a battle against an enemy, before they proceeded to Egypt. While staying in the Egyptian city of Alexandria, Ewostatewos met the Armenian Patriarch Katolikos Jacob II of Cilicia, who had been exiled by his king for his refusal to submit to the Roman Catholic Papacy. Ewostatewos thus decided to visit Armenia without fail, the monk and his followers made a stopover at Cyprus before reaching mainland Armenia. The Ethiopian monk settled and eventually died in the 'Armenian lands' in 1352 and was reportedly buried by the Patriarch himself. His followers, who included the scholars Bäkimos, Märqoréwos and Gäbrä Iyasus later returned to Ethiopia with an Armenian companion and contributed to the composition of their leader's hagiography titled gadla Ēwosṭātēwos (Contending of Ēwosṭātēwos).6

Painted Icon, Double Triptych, 19th century, No. 76.132, Brooklyn museum. inset is Ewostatewos

Icon Triptych: Ewostatewos and Eight of His Disciples, 17th century No. 2006.98, Met museum. Stylized depiction of the Ethiopian monk and his followers

In the suceeding centuries, Ewostatewos' followers became influencial in the Ethiopian church, and would ultimately comprise a significant proportion of the Ethiopian scholars who travelled to the Eastern and Northern Mediterranean in the 15th and 16th century, where they established themselves at the Santo Stefano monastery in Rome. During this time, the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia had fallen to the Mamluks of Egypt, whose expansion south had also led to the collapse of Makuria, leaving Ethiopia as the only remaining Christian kingdom between the eastern mediteranean and the red sea region. Travel by pilgrims, envoys and scholars neverthless continued and contacts between Armenians and Ethiopians remained.

One of the well-travelled Ethiopian scholars at Santo Stefano was Yāʿeqob, a 16th century scholar whose journey took him to the tomb of Ewostatewos in what was then Ottoman Armenia. In his travelogue, which he composed while at Santo Stefano, Yaeqob wrote that;

"I went to Jerusalem, the Holy City, me son of abuna Ēwosṭātēwos and son of Anānyā, who came to the city of Kwalonyā, tomb of the holy ʾabuna Ēwosṭātēwos, me, Yāʿeqob, pilgrim (nagādi), who came down [from the highlands] and when I converted [to monastic life], my name became Takla Māryām, I, dānyā of Dabra Ṣarābi, who wrote trusting in the name of Mary".7

This city of Kwalonya that is mentioned by Yaeqob, which contained the tomb of Ewostatewos, has been identified by some scholars to be the city of Şebinkarahisar in Turkey. However, this location is far from certain and seems to have been on the frontier of the Cilician kingdom. Neverthless, it indicates that the followers of Ewostatewos were atleast familiar with Armenia where their founder was buried, despite the entire region being under the control of the Ottomans by the 16th century. Ewostatewos' tomb would remain a crucial link between Armenians and Ethiopians over the suceeding centuries.

from my article on the history and legacy of Ethiopian scholars in pre-modern Europe, read more about it here:

The beginnings of Armenian travel to Ethiopia.

While the diplomatic contacts between Ethiopia and Cilicia were rendered untenable after the fall of the latter, cultural and commercial contacts between the two regions flourished thanks to interactions between their diasporic communities. Beginning in the 16th century, there were a number of Armenians in Ethiopia who, because of their shared religion, gained the confidence of the Ethiopian elites, and served as the latter's trade agents. Several Armenians in particular served a succession of monarchs as businessmen, and by extension as ambassadors.

The best known of them in this period was Mateus, who in 1541, travelled alongside the Ethiopian envoy Yaʿǝqob to India and Portugal on behalf of Ethiopian Empress Eleni. Mateus had conducted business between Cairo and Ethiopia for many years as a trader and informant for the Ethiopian court, which had co-opted him like many foreigners before and after him.8

Between the 1646 and 1696, the Armenian merchant Khodja Murad served as emissary and broker to three successive Ethiopian emperors, on whose behalf he traveled several times to Yemen, India and as far as Batavia, Insulindia, while his nephew Murad Ibn Mazlum, was delegated to head the embassy designated to the court of the French king Louis XIV. He was later followed by the Armenian bishop Hovannès Tutundji, who travelled from Cairo to Gondär in 1679, where he brought back a relic of the Ethiopian saint Ewostatewos. Another Armenian visitor to Ethiopia from this period was the monk Avédik Paghtasarian, who reached Gondar in 1690. and wrote a work titled “This is the way to travel to Abyssinia” 9

Some of the Armenian travelers to Ethiopia left detailed descriptions of their journey across the kingdom which increased external knowledge about the region.

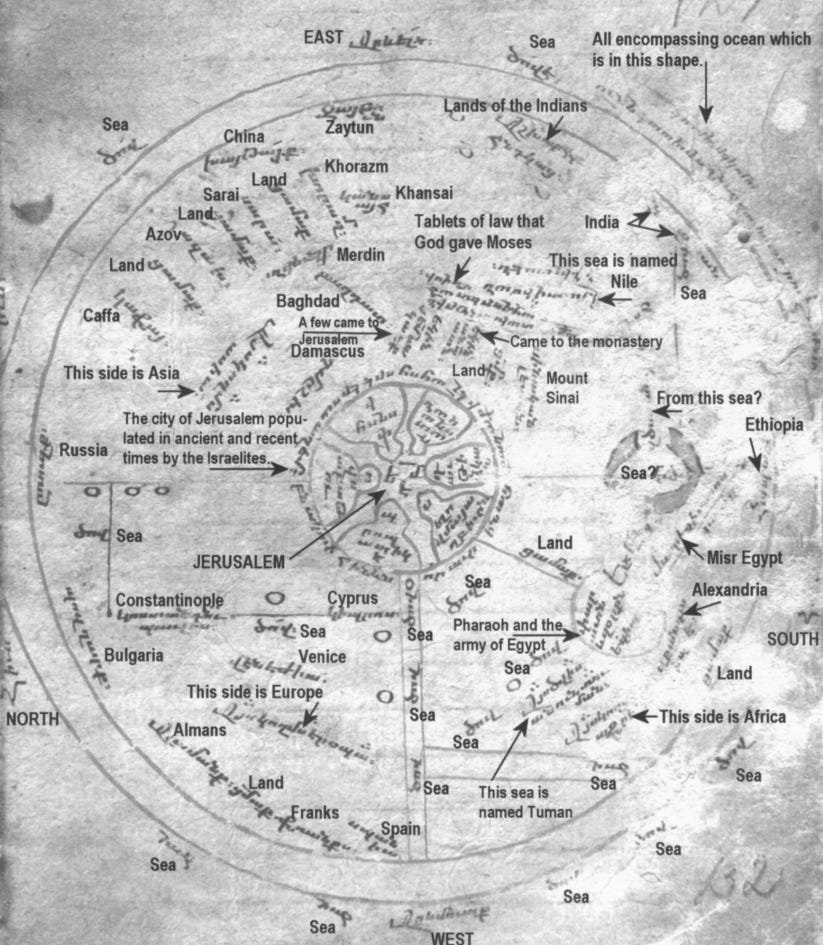

Medieval Armenian T-O map, 13th-15th century, Yerevan, Matenadaran, MS 1242. Ethiopia is shown on the extreme east as ‘hapash’10

The most detailed of these accounts was written by the Armenian traveler Yohannes Tovmacean. He was born in Constantinople but mostly resided in the Armenian monastery in Venice, afterwhich he became a merchant in his later life and travelled widely. He reached Massawa in 1764 and proceeded via Aksum and Adwa to Gondär Where he was appointed as one of the treasurers to Empress Mentewwab before making his way back to the coast in 1766. His travelogue describes many aspects of Ethiopian society that he observed and also mentions several Armenians he found in Gondar such as Stephan, a jeweler from Constanipole and another treasurer named Usta Selef.11

The journey of T'ovmacean took place a few decades before the better known visit of Ethiopia by James Bruce, who also encountered some Armenians at the Ethiopian capital Gondar, writing that;

"These men are chiefly Greeks, or Armenians, but the preference is always given to the latter. Both nations pay caratch, or capitation, to the Grand Signior [i.e. the Ottoman sultan] whose subjects they are, and both have, in consequence, passports, protections, and liberty to trade wherever they please throughout the empire, without being liable to those insults and extortions from the Turkish officers that other strangers are."12

The creation of an Armenian diaspora in Ethiopia

Armenians had been, along with the Greeks and the Arabs, among the only foreigners allowed to travel or stay regularly, and with relative freedom, in Ethiopia during the 17th and 18th centuries when the Gondarine rulers severed relationships with the Latin Christians of southern Europe. The Armenian presence in Ethiopia eventually took on a diasporic dimension with the arrival and establishment of the first real immigrants followed by their families, from the last quarter of the 19th century, especially in northern regions such as Tigray.13

The town of Adwa in Tigray, which was a major center for crafts production, was home to a number of Armenian jewelers and armorers who served the Ethiopian court and church elites. One such Armenian jeweler in the mid 19th century was Haji Yohannes, who was said to have formerly been an illegal coiner, another was an armorer named Yohannes. Armenian craftsmen could be found in other towns such as in Antalo, the capital of Ras Walda Sellase, where there was an Armenian leatherworker named Nazaret, and in Ankobar, where there was an Armenian silversmith named Stefanos. While these goldsmiths and silversmiths did not command a high social position in Ethiopia, they were vital to its urban economy.14

The Armenian community in 19th century Ethiopia weren't only craftsmen but also included influencial figures that played a role in the Ethiopian church. In the 1830s, for example, the provincial ruler of Tigray, Sebagadis, and his successor, had involved an Armenian in a mission to urge the Coptic patriarch of Egypt to appoint an abuna (Patriach of the Ethiopian church).15

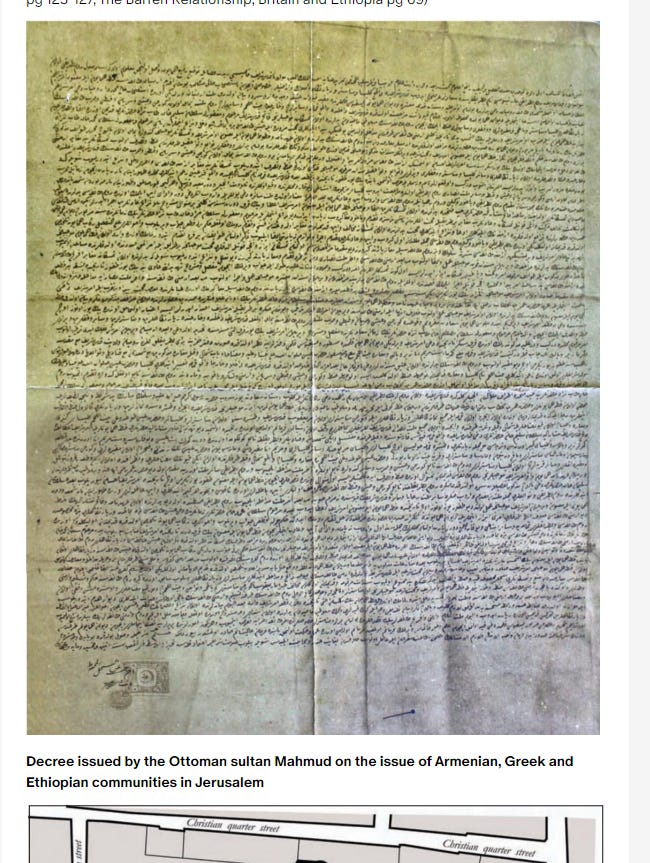

The doctrinal relationship between the Armenian and Ethiopian Churches, as well as the antiquity of their exchanges, ensured that regular contacts were maintained between Ethiopian and Armenian diasporas in the Holy lands. This was especially true for Jerusalem, which remained one of the few foreign destinations of interest to Ethiopians after in the 17th century, and where the local Ethiopian community was placed under the protection of the Armenian community by the Ottoman sultan. The relationship between the Armenian, Ethiopian and Coptic communities in Jerusalem was however, less than cordial, with all claiming control over important sites of worship while leveraging their connections with international powers to support their claim or mediate their disputes.16

From my article on the history of Ethiopians and Nubians in Jerusalem, read more about it here:

One such mediator in the 19th century were the British, who mostly leaned towards the Ethiopian community's side in Jerusalem even as their relationship with Tewodros, the Ethiopian ruler at the time, was in decline. The British thus worked with the Armenian patriarch in Jerusalem who organized a mission to Ethiopia in 1867 that was led by two Armenian clergymen; Dimothéos Sapritchian and Isaac. The two visitors left a detailed description of Ethiopia and were briefly involved in the issue of finding a new abuna, with Isaac almost assuming the role, but the appointment was ultimately made in the time-honored way, following nomination by the Alexandrian Patriarch. The two Armenian clergymen eventually left Ethiopia in 1869.17

The Armenian community in Ethiopia would continue to flourish under Tewodros' sucessors, especially during the reign of Menelik II (1889-1913) when they numbered around 200 and later exceeded 1,000 by the 1920s, following the genocide of Ottoman-Armenians and a major wave of migration of Armenians to Ethiopia. Just like their predecessors, many of the Armenians served in various capacities both elite and non-elite, often as craftsmen, traders and courtiers. Under the patronage of Menelik and his sucessors, the Armenian community in Ethiopia was naturalized and eventually came to regard Ethiopia as a ‘diasporic homeland’, a sentiment which continues to the present day. 18

Members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, holding the Ethiopian flag in 1910. (Photo courtesy of Alain Marcerou)

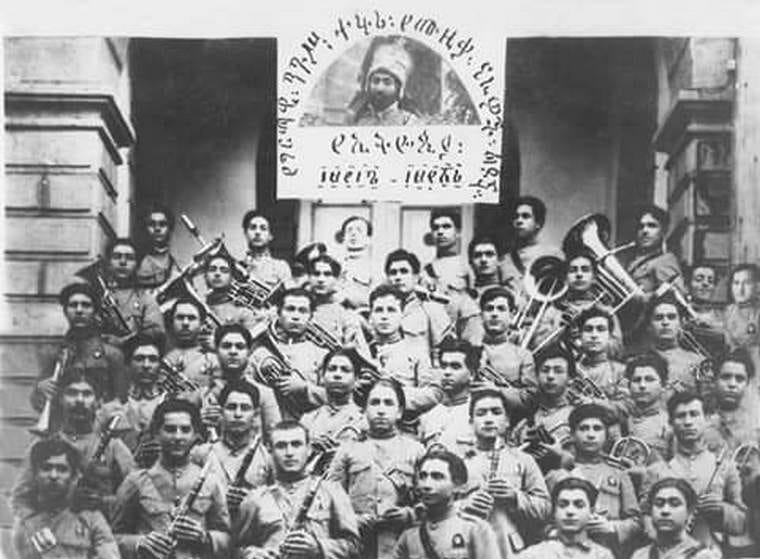

the 'Arba Lijoch', imperial brass band of Haile Selassie, early 20th cent. The Arba Lijoch were 40 Armenian orphans who escaped the Armenian genocide and were adopted by Selassie while he was in Jerusalem in 1924.

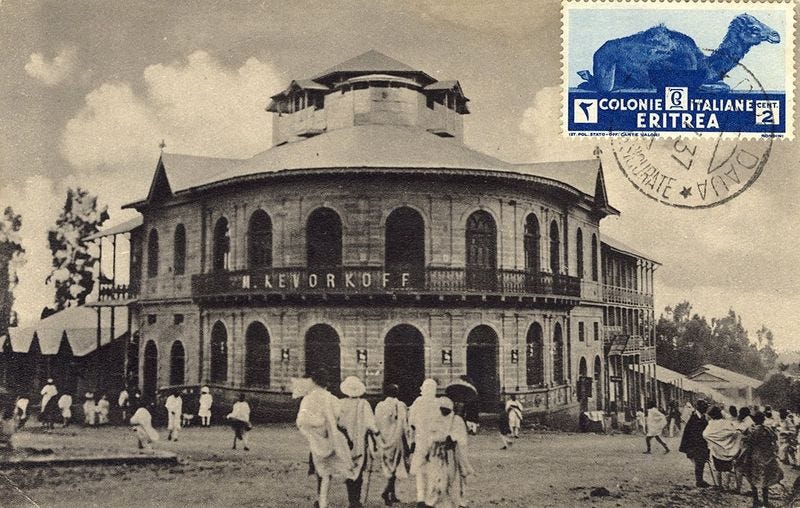

Historic postcard of the Kevorkoff Building in Dire Dawa, Ethiopia. associated with the Armenian businessman Matig Kevorkoff

Saint George Armenian Apostolic church, Addis Ababa, built in 1935

Ethiopia is one of the few places in the world that developed its own notation system, and is home to an one of the world’s oldest musical traditions.

read more about it in my latest Patreon essay;

Armeno-Aethiopica in the Middle Ages by Zaroui Pogossian pg 117-119)

Nubia, Ethiopia, and the Crusading World by Adam Simmons, A Note towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora by Adam Simmons pg 27-29, A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea by Samantha Kelly pg 434)

Africa and Byzantium By Andrea Myers Achi pg 157, 165

A Note towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora by Adam Simmons pg 29)

Écriture et réécriture hagiographiques du gadla Ēwosṭātēwos Olivia Adankpo

Dictionary of African Biography, Volumes 1-6 pg 320, The History of Ethiopian-Armenian Relations by R. Pankhurst,

A companion to religious minorities in Rome by Matthew Coneys Wainwright pg 177-185)

Les Arméniens dans le commerce asiatique au début de l'ère moderne: Armenians in asian trade in the early modern era by Sushil Chaudhury, pg 121-127

Foreign relations with Ethiopia: human and diplomatic history (from its origins to present) by Lukian Prijac pg 14, Les Arméniens dans le commerce asiatique au début de l'ère moderne: Armenians in asian trade in the early modern era by Sushil Chaudhury pg 128-145

A Medieval Armenian T-O Map by Rouben Galichian

The Visit to Ethiopia of Yohannes T'ovmacean: An Armenian Jeweller in 1764-66 by V. Nersessian and Richard Pankhurst

A Social History of Ethiopia by Richard Pankhurst pg 103)

Les Arméniens en Éthiopie, une entorse à la « raison diasporique » ? by Boris Adjemian pg 108-113)

A Social History of Ethiopia by Richard Pankhurst pg 235-238)

An Armenian Involvement in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Ethiopia by David W. Phillipson pg 142)

The Monk on the Roof: The Story of an Ethiopian Manuscript Found in Jerusalem (1904) by Stéphane Ancel

An armenian involvement Mid-Nineteenth-Century Ethiopia by David W. Phillipson pg 137-143)

Immigrants and Kings Foreignness in Ethiopia, through the Eye of Armenian Diaspora by Boris Adjemian

Do we have that same psalm fragment in Old Nubian as well.