Knights of the Sahara: A history of military horses and equestrian culture in Africa (1650BC-1916AD)

the role of cavalries in the political history of Africa's Saharan states

Since its domestication 5,000 years ago, the horse has played an important role in statecraft and warfare. In the ancient world, the charioteer carried in a horse-drawn vehicle became the world’s first war machine, greatly reshaping the political landscape of the near-east, and in the medieval era, mounted soldiers became a powerful military class, dominating the politics of the middle ages from the European knight to the central-Asian Mamluks.

Because of its importance in Eurasian history, the military horse’s role has often been stressed in the political history of the African states straddling the Sahara desert, and while earlier theories that attributed African state formation to mounted invaders from the north have since been discredited, scholarly consensus maintains the importance of cavalry warfare in Saharan state history, a region that was home to virtually all of the continent’s largest empires.

This article traces the history of the horse in Africa from its earliest adoption in warfare during antiquity, to the end of the mounted soldier in the colonial wars of the early 20th century.

Map showing the distribution of recent horse population in Africa and the approximate location of Saharan states mentioned below.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Early evidence for horses in the Saharan regions of Sudan and West Africa

Archeological finds and Saharan Horse art before the 16th century

The earliest evidence for the use of war horses comes from the Kerma-controlled sites of Nubia at Buhen in 1675 BC and at sai island in 1500BC where horse skeletons were found, and its from Kerma artists around 1650–1550BC that we get the oldest representation of horse-drawn chariots in the Sahara at the site of Nag Kolorodna near the Sudan/Egypt border.1 After the re-emergence of the kingdom of Kush in the first millennium BC, horse burials appear frequently across the Nubian region , at Tombos in 1000BC and at Kush's royal cemetery of el-Kurru from 705BC to 653BC2, After which representations of horses become nearly ubiquitous across Kush's territories especially on temple reliefs depicting victory scenes and in Kush's literature. The Kushite horse burial tradition continues at Meroe from the 2nd century BC3, and into the post-meroitic era at the 5th century sites of Qustul and Firka.4

victory relief from Nag Kolorodna in lower nubia showing the ruler of Kerma on a throne and a wheeled chariot driven by horses, dated to between 1650-1550BC

illustrations of horse-drawn chariots in various relief scenes taken from taharqo’s temple at sanam in sudan, built in 675BC 5

Horses were present in west African sahara since the mid 1st millennium BC. Cave paintings depicting horses appear across the region and include representations of cavalry warfare in the western Sahara near the dhar tichitt neolithic culture in southern Mauritania (2200-400BC) , that were likely made near its end in the late 1st millennium BC.6 Excavations at kariya wuro near Bauchi in Nigeria have yielded horse teeth dated to 2000BP, and at the site of igbo Ukwu in south-eastern Nigeria, a bronze hilt of a man on horseback was dated to around 1000AD.7 Several equestrian figures and horse-bits appear in the Niger-river bend and inland-Niger delta regions dated to between the 3rd and 10th century from the Bura civilization, and between the 12th to 15th century from the Djenne civilization8.

Equestrian figure from Bura dated to the 3rd and 10th century (at Universite Abdou Moumouni de Niamey, Niger), Equestrian figure from djenne dated 12th-16th century, (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City)

cave painting of a cavalry battle scene from Guilemsi near dhar tichitt in southern mauritania

Internal and external writing on Saharan horses before 1500

The earliest textural references of war horses in the Sahara come from the chronicles of the kings of Kush beginning with the great triumphal stela of King Piye made in 727BC, that includes a complaint by the 25th dynasty founder, who recorded his outrage at the state of the neglected war horses of Egypt that had been left to starve in the stables, the same stela also includes presents of horse tributes from the Egyptian kinglets he had conquered9. References to horses and chariots and their importance in Kush's royal iconography feature frequently in Kush's records throughout the Napatan era from the 8th to 4th century BC10. Horses bred in Kush also appear across various near-eastern sources especially in the Assyrian empire, whose rulers were eager to acquire the high-quality kusaya breed from Kush that was favored by Assyrian charioteers. Virtually all the chariot horses mentioned in the “nineveh horse reports” are designated as Kushite, the Assyrian capital also had a section occupied by Kushite horse trainers who were in charge of the care and handling of royal stables.11 Horses continue to feature prominently in the Christian Nubian era, although internal textural references about them are sparse, external records contain frequent mentions of horses in the kingdoms of Makuria and Alodia with the 10th century writer al-Aswani who wrote that the Alodian cavalry was much larger than that of Makuria with "excellent horses and tawny camels of pure Arabian pedigree".12 which is more likely a reference to their quality rather than their origin as no exports of Arabian horses into Nubia are mentioned by him or other writers.

6th century representation of the Noubadian King Silko on horseback spearing an enemy. inscribed on the wall of the Temple of Mandulis at Kalabsha.13

In west African saharan regions, there's strong linguistic evidence for the antiquity of the horse, with no European (1500CE-) Or Arabic (800CE-) loan-words, the great diversity of West African equine vocabulary, with its large number of apparently unrelated roots, suggests that the spread of horses within West Africa took place in relatively remote times.14 While internal writings on war horse are sparse, external writings contain frequent mentions of war horses and other domestic horses in the region, Al-muhallabi in 985 writes that the people of the Gao kingdom rode horses bareback, Al-Bakri in 1067, noted that the ruler of Ghana gave audience surrounded by horse caparisoned in gold while Al-idrisi in 1154, noted that the ruler of Ghana tethered his horse to a gold brick, Al-Maqrizi writing in 1400, notes the horses in the armies of Kanem-Bornu.15 In the 1340s. Al-'Umari reports that the king of Mali commanded a force of no less than 10,000 cavalry, and was importing horses from northern Africa to supply mounts for his soldiers, in the 1350s, Ibn Battuta alludes to mounted chiefs and retainers at the Mali court, and to the practice (recorded earlier in Ghana) of keeping horses ready for the king when he held an audience.16 By the early 2nd millennium, horses were too widespread across the Sahara and had been present for too long to be treated in internal African texts as noteworthy innovations on their own, instead, local accounts especially in west African, are concerned with the introduction of new techniques of cavalry warfare, associated with larger horse breeds and new equipment. There are now several recognized "races" of horses in Africa, including the Dongolawi, kordofani, Songhai, Borana, Somali, Kirdi, Kotokoli, Torodi, Manianka, Bobo, Koniakar, M'bayar, Cayar, among others.17

The use of "small" versus "large" by external writers (both Arab and European) in describing most of the horse breeds of Africa is mostly used relative to their own horses (which measured 13 to 17 hands in height), and can't easily be used to distinguish between African horse breeds since, save for the Dongola breed (from Sudan) and the barb breed (from north Africa) that averaged 14 to 16 hands, Saharan horses are often around 14 hands in height and are at times called 'ponies’ by external writers18 The slightly smaller height is due to “dwarfing” of the horse partly as a form of resistance against the tripanosomiasis disease caused by the trypanosoma brucei which is carried by the tse-tse fly, the prevalence of the disease increases south as one moves away from the desert where there is no tse-tse fly to the forest region where its most prevalent. Pre-modern external observers from the 13th century to the late 19th century had no knowledge of the disease and often attributed its symptoms to the local climate, reports of high mortality among west African horses were frequent especially at distances relatively far from the Sahara, the explorer Binger in the 1880s stated that the horses of Samori's Wasulu army (in modern Guinea) had to be replaced four times in nearly two years—an average life expectancy of under six months, and a French colonial officer estimated that to the south of the latitude of 11°, northern horses would have to be replaced, on average, every two years. Saharan horse societies mitigated the effects of the tse-tse fly and other pests by using horses sparingly during the wet seasons, washing the horses in fly-repellant fluids and occasionally smoking the stables.19

tse-tse fly distribution map in the late 20th century

Horse breeding and trade in the Saharan states

The origins of horse breeding in Sudan can be traced back to Kush in the 8th century BC, where the practice was undertaken as part of the development of the Kushite chariotry following Piye's accession; his innovations included the introduction of better and larger horses, heavier chariots with three men to each chariot, and the development of cavalry tactics20. The horses which were buried in the el-Kurru royal cemetery of Kush (a tradition introduced by Piye) measured 155.33 cm in height (ie: over 15 hands) and were large even by modern standards. The practice of Kushite horse-breeding must have been done on an extensive scale to meet the demand for their exportation as the abovementioned Assyrian records mention the purchase of more than 1,000 horses from Kush compared to just 85 ‘Iranian’ horses.21 Despite little mention of Christian Nubia’s horse-breeding in external record, the practice likely continued in the Dongola-reach. where it had been based since the Kushite era.22 After the fall of Christian Nubia in the 15th/16th century, the Dongola-reach fell to the Funj kingdom in the 17th century, becoming the northern-most province of the kingdom which was by then based at sennar.23 the mek of Dongola (title for a vassal of the Funj kingdom), paid tribute in horses to sennar24, and this horse tribute formed the bulk of the Funj kingdom's exports, which were exported as far as Yemen in the east through the port of suakin, to Bornu in the west, and to Darfur in the south.25

a Dongola horse, measuring 1.53 m high at the withers, and 435 kg in weight (1912 photo)26

In the west African sahara, the breeding of larger horses locally was undertaken not long after their importation from sudan (the Dongola breed) and north africa the barb breed) with evidence coming from Bornu in the 16th century where local breeds of "Bornu horses" begun substituting the imported horses27. Leo Africanus, writing in the 16th century, mentions that horses were bred at Timbuktu and Kawkaw (presumably the capital Gao) for the Songhai cavalry while the larger horses were bought across the desert.28 After the 17th century, horse-breeding was fairly widespread across west Africa including in the Sene-gambia region in the 18th century, in the 19th century Massina kingdom by the policy of its ruler Seku Ahmadu (r. 1818–1884), who established local studs in order to secure self-sufficiency in cavalry mounts, pure Dongola horses were also bred in early 19th century Bornu and stood at between 15 and 15½ hands' height, in 19th century Sokoto, horse-breeding was established by policy of Sultan Muhammad Bello (r. 1817–37),29 the area of Mandara to the south of Lake Chad was noted for breeding very large horses, of between 15 and 17 hands, presumably a variant of the Dongola horse deliberately bred for size.30 The large-scale breeding of horses in Saharan states was also connected with the frequent appearances of horse tributes in various kingdoms across the region that were oftentimes collected from their nomadic subjects; such as the subordinate Arab tribes and other groups. The annual tribute received by Bornu from the busa nomads was 100 horses31, the annual tribute that the Wadai rulers received from its salamat arab subjects was 100 horses among several other items, while Bagirmi also received tribute of 100 horses from 4 of its vassals along the chari river32 and from its shuwa arab vassals among several other items33. Darfur also received horse tribute from its northern vassals34 The sene-gambian kingdoms of Diara and jolof also received tribute in horses during the 15th century, as well as in Sokoto, Mandara, in the Jukun kingdom, and in the Igala kingdom in the 18th and 19th century35

horse riders of the Mandara, cameroon (1911/1915 photo, German Federal Archives)

Import of horses into the Saharan states

There are virtually no mentions of imports of horses into ancient Kush and medieval Christian nubia since the region was itself a major horse-breeding center of the Dongola breed. In west African Sahara, large numbers of imported horses are only mentioned prior to the mid 16th century, Ibn Battuta writing in the 14th century, mentions that each horse imported from morocco into Mali was bought at the price of 100 gold mithqals, a significant amount that Mali must have been expended on its 10,000-strong cavalry36 Leo Africanus in the early sixteenth century, records that Kanem-Bornu king Idris Katagarmabe (r. 1497–1519) imported large numbers of horses from North Africa and built up a force of 3,000 cavalry figures.37 Reports of horse imports fall after 16th century with only a few hundred or less imported into Bornu from Fezzan and Tunisia in the 17th century (presumably because of substitution from local “bornu” breeds, or just as likely, because of imports from Funj kingdom since Dongola horses were more common in Bornu) and in the 1780s, there is a report of merchants from the Fezzan taking horses for sale in Katsina in Hausaland, while in the sene-gambia region, the Portuguese traders briefly engaged in a lucrative horse-trade during 15th/16th century but the trade died out shortly after due to a drastic drop in horse prices following the substitution of imports with local breeds.38

There was significant trade within African kingdoms themselves between the horse-breeding regions in the Sahara and the none-horse breeding areas in the forest regions near the coast. For much of the 17th to 19th century, the principal exporter of horses, were the kingdoms of Funj, Bornu and Yatenga. The Dongola horse from the Funj kingdom was the most sought after breed across much of Africa east of the Niger river, these horses were often praised in external accounts such as the 18th century explorer James Bruce who described them as the "noble race of horses justly celebrated all over the world" and the 19th century traveler John Burckhard who writes that "the (dongola) horses possess all the superior beauty of the horses of Arabia, but they are larger". In the 17th and 18th century, the Funj kingdom controlled most of this trade which it channeled from Dongola to its capital Sennar where the horses were then exported across the region39 to Bornu and Wadai in the west, to Darfur and Mandara in its south, to Ethiopia and Yemen in its east. especially in Ethiopia where the 18th century cavalry was equipped with both horses and armor from sennar,40 In the late 18th and early 19th century following Funj's disintegration, the export trade was in the hands of semi-autonomous kingdom of Dongola, which weathered its overlord's fall and increased its exports across the region.41 The kingdom of Bornu exported horses to Hausalands (especially the city-states of Kano and Zaria), as well as to the kingdoms of Wadai and Bagirmi, as well as into north africa in the Fezzan where trade in Bornu horses is mentioned. Bornu’s horses were also re-exported further south into the Yoruba-lands especially the kingdom of Oyo which amassed a large cavalry in the 17th and 18th century. Yatenga war horses (as well as pack animals) were traded to other Mossi kingdoms and in Northern Ghana, while in the sene-gambia and Mali, horses were purchased from the Soninke (Dyuula) traders and southern Berber nomads of southern Mauritania, where they were sold to the southern kingdoms of Wolof, Kaarta and Samory's Wasulu empire.42

map of horse-breeding and horse-trading regions in west africa.43

Relationship between the rider and their horse

"[the fact] that my horses were made to hunger pains me more than any other crime you committed in your recklessness" Piye to the Egyptian kinglets in 727BC44

Across the Saharan states, horses were usually kept in stables in their owner's compound, or more commonly within the Kings's palace complex because the cost of maintaining a horse was usually much higher than the cost of breeding or importing it, often requiring a steady supply of fodder comprising of grass and corn, which for royal stables such as in Songhai, Bornu and Nupe, was easily obtained through tribute or gathered from nearby plantations (as mentioned in a number of west African chronicles), but for the rest of horse-owners, the extended family was in charge of gathering fodder and caring for the horse, while for travelers and itinerant traders, their horse fodder was bought from local markets45.

In the ancient kingdom of Ghana, according to traditions recorded in the seventeenth century, each of the king's 1,000 horses had three attendants, one to provide its food, one to supply its drink, and one to keep its stable clean of dung. Generally however, the ratio of one attendant per horse is reported across most kingdoms such as Mandara, Gonja, Wagadugu, and these were usually headed by palace officials in charge of the horses such as the “olokun esin” (holder of the horse's bridle) in Oyo and the shamaki in Kano46. Similar offices were observed in the kingdoms of Darfur and Funj where melik el-hissam who was the guardian of the royal stables, and various other figures with the title korayat who were incharge of various horse equipment and armor47

The relationship between the rider and their horse is perfectly encapsulated in this quote from a Berom man in central nigeria: "A horse is like a man, you send it out to bring a tired man home, you give it water to drink, you walk miles to find it grass to eat, it carries you to hunt and to war, when you die, and they lead it towards your grave, its spirit may fly out of its body in its anxiety to find you.".48

a rider rearing his horse in Dikwa, Nigeria

Horse equipment and armour

Horse harnesses were in use in Kush since the adoption of chariotry in the 16th century BC, but after the decline in the use of horse-drawn chariots in warfare at the turn of the common era, they were replaced with mounted soldiers. Horse-riding equipment such as bridles (head-straps that direct the horse), saddles (a leather seat for the rider) and stirrups (frames that hold the rider’s feet) were quickly adopted in the kingdoms of medieval Christian nubia where they enabled the Nubians to raise cavalry forces early by the 6th century. In the west African Saharan states, the combined use of the saddle, stirrups and bridles post-dated the adoption of the horse before the common era, but likely coincided with its use in cavalry warfare after the 13th century49. Different forms of bridles had been in use during antiquity and a combination of all or some were represented in west African rock art as well as in old sculptures such as Bura, Djenne and in the forest regions far from the Sahara such as Igbo Ukwu, Ife and Benin. The most common form of the bridle in Saharan Africa is attested in several Nubian burial sites and wall paintings, it comprises of a headband, headpiece, cheek straps, noseband, jaw strap and a additional strap running down between the Horses's eyes from the headband to noseband.50 This same type of bridle also appears on the terracottas of Bura (below), in Jenne and in Ife and Benin.

detail of the bura equestrian showing the horse’s reins. horse-bits from the bura civilization dated 3rd to 10th century (at the yale university art gallery 2010.6.37)

The earliest evidence for the use of the saddle in nubia comes from the 6th century horse burials at Qustul, and the earliest depiction of the stirrup is from the Nubian wall paintings of the Faras cathedral dated to the 10th century51 while in saharan west africa, the first mention of both the saddle and stirrup in west Africa comes from al-Umari's and Ibn batutta's description of Mali empire in the 14th century, and the first mention of both in the sene-gambia region, was made by Portuguese writers in the 1450s just before they begun exporting them to the region.52 Across the Saharan states, this horse equipment was often manufactured locally, where crafts guilds specializing in leather-making and iron smelting supplied horse-bits and their leather straps, stirrups, and decorated saddle cloths which were attimes gilded with gold ornaments eg in Bornu.53

detail of the 10th century nativity mural from Faras cathedral, kingdom of makuria showing the magi on horseback with their feet in stirrups

Cavalry armor was introduced into the Saharan states at the same time as the horse riding equipment. the 16th century kanuri chronicler Ibn Furtu mentions the extensive use of both quilted cloth armour and chain mail in Mai idris Alooma's armies, although this wouldn’t have been their date of introduction in the region, and they would had been in use for much longer by then in the empires of Mali and songhai54 given the frequent mentions of mail-coats in the 16th century Songhai armies in the 17th century chronicle of timbuktu,55 as well as references to the use of lifidi (quilted cloth horse armor), sulke (chain mail), and metal helmets, by the mounted soldiers of Kano’s king Kanejeji (r. 1390-1410), which he acquired from his wangara advisors that had come from Mali, as recorded in the 19th century Kano chronicle.56 In the cavalry armies of Funj and Darfur, the riders often wore chain-mail tunics, as well as quilted cloth armor and spiked iron helmets, their horses were also clad in quilted cotton with metal chamfrons on their heads and breastplates.57 West africa’s Saharan horsemen also wore metal plate armour of cuirasses in Bornu and Sokoto, as well as long riding boots of leather to give some protection to their thighs. The horse was also protected with a quilted cotton, which covered the whole body and the neck, hanging down over the hindquarters and the chest, and the horse's chest was protected by a breast-plate of leather or metal while the horse's head was often also protected by a metal chamfron or head-piece.58

19th century Quilted armour of the Mahdiya in sudan (british museum Af1899,1213.2), Mundang horsemen in cameroon (Pictures by Mission Moll, 1905-1907)

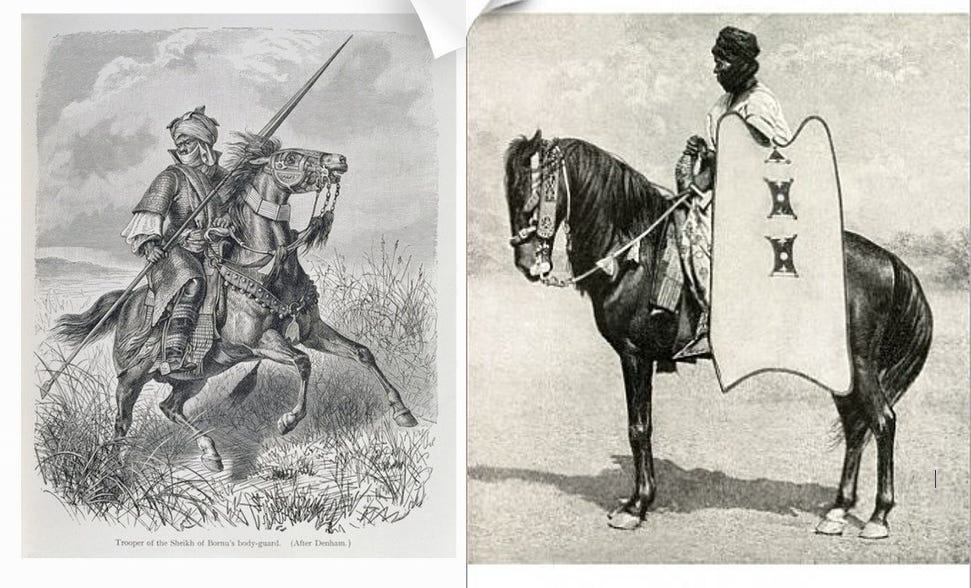

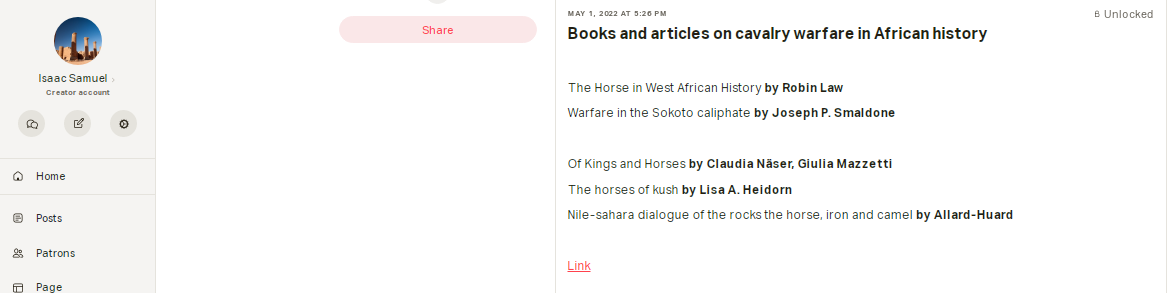

Horseman of the bodyguard of Bornu, shown with a coat of chainmail, the saddle and bridles are also visible (illustration from Dixon Denham in the 1825). Horse and rider with large oryx hide shield, Sokoto, Nigeria, photograph taken 1922

Cavalry warfare and African statecraft in the Sahara

The methods of building up cavalry forces in Saharan states were diverse, in the kingdoms of Funj and Darfur, rulers often granted estates to their chiefs who then used the revenues from those estates to purchase horses, equipment and armor that they gave to the kings' soldiers in time of war, in an almost classic feudal style.59 In the west Africa’s Saharan states however, the majority of rulers owned and distributed the horses, equipment and armour to their soldiers and subordinate chiefs, rather than relying on feudal leeves from the latter, but the high cost of maintaining the horses forced the rulers to transfer the cost to the chiefs who fed and handled the horses, thus limiting the cavalry's centralized control, so while the classical feudal army was inhibited by rulers controlling the distribution, complete centralization was unattainable due to the high cost of maintenance.60

In the Saharan states that used horses in warfare, there was a built-in stratification between the mounted soldier and the foot-soldier, the long investment required to produce and arm a trained horseman positioned them at the center of a system that exploits surplus production, and the necessity of centralizing authority over the mounted soldier put the cavalry in a position to demand a share of political power and led to the development of a "knightly ethic".61 The ratio of cavalry to infantry in Saharan states often varied from 1:3 to 1:10, eg, the Mali empire reportedly had 10,000 cavalry and 90,000 infantry, the kingdom of Bagirmi is said to have had 15,000 forces with 10,000 men in the infantry and 5,000 men in the cavalry, while Wadai is said to have had between 5,000 and 6,000 men in its cavalry alone, and Darfur had some 10,000 soldiers in its army with about 3,000 mounted soldiers.62 Songhai had 12,500 cavalry and 30,000 infantry in 1591, while Sokoto had 5,000- 6,000 cavalry and 50-60,000 infantry in 1824.63

Bornu mounted soldiers in ceremonial battle dress (photo from 1906), wadai cavalry (photo from early 20th century)

Weapons and Battle

Training of horsemen was usually undertaken by riders individually, as well as at equestrian ceremonies that were held annually like the durbar festivals in the Hausa lands, which afforded horsemen the opportunity to perform maneuvers simulating warfare and the use of weapons from horseback.64 Jolof horses were so well trained that they followed their owners around like dogs. The riders performed tricks and feats of equestrian skill, such as leaping on and off galloping horses, and retrieving lances from the ground without dismounting, clicking their heels together from the back of a charging mount, or reaching from horseback to erase the horses’ hoofprints with their shields.65

Before the 18th century, the principal cavalry weapon was the lance for thrusting, other weapons include the sword for slashing and the javelin for throwing. In Darfur and Funj, the favored weapon was the long broad-sword, the mace and the long heavy-bladed lance66, a division between the heavy and light cavalry was observed, of the 3,000 cavalry troops, only about 1,000 were heavily armoured, while the rest were light cavalry forces.67 In the western Saharan states, the preferred weapons for cavalry was the heavy metal lance about six feet long and various swords68, the mounted forces were often divided into heavy and light cavalry, with the heavily armored troops often numbering a few hundred who carried only the lance and sword, whereas lightly-armoured cavalry which comprised several thousand, fought with lances and javelins.69

In battle, cavalry normally fought in combination with infantry forces. While in Darfur and Funj, the cavalry forces usually charged ahead of the troops70, In Bornu and Mandara, the infantry led the charge with the cavalry force behind it, as one observer of Bornu’s armies in the 1820s noted “The infantry here most commonly decide the fortune of war; and the sheikh's former successes may be greatly, if not entirely, attributed to the courageous efforts of the Kanem spearmen, in leading the Bornou horse into battle, who, without such a covering attack would never be brought to face the arrows of their enemies”, similar observations were made in the kingdoms of Nupe, Mossi and Dagomba. Alternatively, cavalry could be positioned on the front and sides, making up both the striking force for frontal assault as well as to outflank them, as observed in the armies of Zinder, Zaria and Gobir.71

Bornu cavalry charge (illustration by dixon denham, 1825)

A new military order: the foot soldiers’ fire-arms and the gradual end of Saharan equestrianism.

Despite presenting a formidable military force, cavalry armies were far from invincible and infantry forces had a number of defenses they could put up against cavalry charges which eventually proved especially useful for armies on the periphery of the Saharan states. In the 17th century, Benin is said to have dug pits in which the enemy cavalry of Igala was entrapped and the motif of the defeated enemy on horseback appears frequently in Benin’s art, while the armies of Dahomey and Ibadan in 19th century attacked the cavalry armies of Oyo and Ilorin at night72, In the 1740s and 1818, the cavalry armies of Dagomba and Gyaman were defeated by the infantry armies of Asante and forced into a tributary status.73

16th century Benin plaques depicting defeated enemy captives on horseback, the first one shows the captive being dismounted for execution, while the second shows the captive being forcefully led away by a Benin soldier (Af1898,0115.48, Af1898,0115.47 at the british museum)

While the increased importation of firearms gradually undermined the military effectiveness of cavalry, the mounted soldier wouldn’t be rendered obsolete until the late 19th century, and the incorporation of fire-arms into the cavalry proved rather useful in after the 18th century, where mounted riflemen in the armies of Sokoto, Rabih az-Zubayr and Samory’s Wasulu could fire their guns on horseback, the relatively modern guns could be reloaded on horseback, while the older guns were reloaded by attendants,74Similarly in Darfur, cavalry forces attimes carried fire-arms which they personal side-arms and were fired in the opening salvos of battle.75

Despite the very early adoption of fire-arms in the Saharan militaries such as Bornu’s arquebusiers in the 16th century, the restriction of their imports from both the Atlantic and Mediterranean states meant that guns were used sparingly, and only a few hundred of the thousands of mounted soldiers carried them well into the 19th century, and firearms appeared infrequently in the armies of Darfur, Bornu, Sokoto, and Wadai, (with the brief exception of Zinder whose army in the 1850s had atleast 6,000 musketeers and several canon, some of which were produced locally).76 The small number of fire-arms in Saharan forces pales in comparison to the infantry armies of Asante and Dahomey where the entire force of 15-30,000 were often armed with fire-arms and in the horn of Africa, where half of the 80,000-100,000 ethiopian troops were armed with rifles. Imports of firearms slightly increased in the late 19th century such in the armies of Shehu Umar of Bornu in 1870s and Rabih in the 1880s, although these were old rifles, and the Saharan forces continued to rely on their cavalry.77

Horseman of the Tukulor empire armed with a musket (illustration by Joseph Gallieni 1891)

Between the fall of Ilorin in 1897, and the capture of Darfur’s forces in 1916, the knights of the Saharan states put up their last defense against the onslaught of the colonial armies which were mostly on foot and wielded the latest quick firing guns. In 1910, the 5,000 strong cavalry of Dud Murra (the last sultan of Wadai) won the last victory fought by a Saharan mounted soldier when they defeated two French columns led by Fiegenschuh and Maillard, wiping out nearly 1,000 of the enemy troops armed with modern rifles, before he was eventually forced to surrender in 1911.78 the armies of Darfur's Ali dinar would succumb to a similar fate at the battle of Beringia in 1916 against the British maxims, marking the end of the equestrian age in the Sahara.

the last hurrah of the African knight. illustration in a french newspaper of the armies of Dud Murra made in February 1911, shortly after the wadai sultan had defeated the french in December 1910.

With the end of colonial warfare in the Sahara, military horses lost their major function, the Saharan horse-stables fell into disrepair, horse breeding and trade collapsed and the relics of the African knights in quilted armour were donated to museums. Informants in West Africa nowadays, when asked to explain the decline of horse-keeping, regularly reply, simply, that there is no longer any war79 … at least not the kind of war that requires horses.

Durbar horse racing festival in Kano, Nigeria, 2016.

Read more about African cavalries and equestrian cultures on my Patreon

THANKS FOR SUPPORTING MY WRITING, if you haven’t seen some of my posts in your email inbox, please check your “promotions tab” and click “accept for future messages”.

Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 190-191

Of Kings and Horses by Claudia Näser, Giulia Mazzetti

The Kingdom of Kush by L Torok pg 445)

The Medieval Kingdoms of Nuby Derek A. Welsby pg 81, 44)

Nile-sahara dialogue of the rocks the horse, iron and camel by Allard-Huard pg 28-29

Rock Art from the Dhar Tichitt augstin holl

The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns by T. Shaw et. al pg 92)

sahel art and empires by Alisa LaGamma pg 81-87)

The horses of kush by Lisa A. Heidorn pg 105-106),

The Kingdom of Kush by L Torok pg 157-158)

The horses of kush by Lisa A. Heidorn pg 106-110)

kingdom of alwa by Mohi el-Din Abdalla Zarroug · pg 20)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia by Bruce Williams pg 716

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 5-7)

The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns by T. Shaw et. al pg 93)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 10)

The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns by T. Shaw et. al pg 89)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 25)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 77-81)

The Kingdom of Kush by L Torok pg pg 158)

Of kings and horses by Claudia Näser, Giulia Mazzetti pg 128-129)

Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia by Derek A. Welsby pg 184

Kingdoms of the Sudan By R.S. O'Fahey, pg 63

Islamic Archaeology in the Sudan by Intisar el-Zein Soughayroun Pg 44

The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa by T. Insoll pg 119)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 29)

The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns by T. Shaw et. al pg 94)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law 44-46)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 24)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 20)

Sahara and Sudan: Wadai and Darfur by Gustav Nachtigal pg 98, 171, 182, 700

Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab Settlements By Augustin Hol pg 20-24

State and Society in Dār Fūr By Rex S. O'Fahey pg 84

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 191)

Ibn Khaldun: The Mediterranean in the 14th Century by Fundación El legado andalusì pg 119

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 17

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 48-53)

The horses of kush by Lisa A. Heidorn pg 111-113)

Ingessana: The Religious Institutions of a People of the Sudan-Ethiopia Borderland by M C Jedrej pg 13)

The kingdoms of sudan by R. S. O'Fahey pg 100-104)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg pg 54-58)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 42,54

Of kings and horses by Claudia Näser, Giulia Mazzetti pg 130)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 74

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 76

Sahara and Sudan: Wadai and Darfur By Gustav Nachtigal pg 336

The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns by T. Shaw et. al pg 96)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 121-122)

The medieval kingdoms of nubia by Derek A. Welsby pg 81)

The medieval kingdoms of nubia by Derek A. Welsby pg 81

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 89-105)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 108-110)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 123-124)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by J.O.Hunwick pg 165, 171

Government In Kano, 1350-1950 by M.G. Smith pg 120)

The kingdoms of sudan by R. S. O'Fahey pg 52-53)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law 130-132)

Land in Dar Fur: Charters and Related Documents from the Dar Fur Sultanate by R. S. O'Fahey pg 13-14)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law 191-192)

The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns by T. Shaw et. al pg 100-101)

Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, V. 2:1849–1895 by H. Barth pg 527, 530, 560

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 137)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 147, The History and Performance of Durbar in Northern Nigeria by Abdullahi Rafi Augi pg 15, 16

warfare in Atlantic africa by J.K.Thornton pg 26

State and Society in Dār Fūr by Rex S. O'Fahey pg 96, The kingdoms of sudan by R. S. O'Fahey pg 53)

State and Society in Dār Fūr by Rex S. O'Fahey pg 96)

Warfare in the Sokoto caliphate by Joseph P. Smaldone pg 46-47

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 128-129)

The kingdoms of sudan by R. S. O'Fahey pg 53)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 133-134)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 135-136)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 12, 15)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 145-6)

State and Society in Dār Fūr by Rex S. O'Fahey pg 96)

Warfare in sokoto by Joseph P. Smaldone pg 94-100)

Warfare in sokoto by Joseph P. Smaldone pg 101)

The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad by Mario Azevedo pg 51-52)

The Horse in West African History by Robin Law pg 204)

A wonderfully informative article. Thank you for sharing it with us

It's amazing how much we still have to learn about West Africa or African history in general like the horses importance in African cultures and history is such an interesting topic. We know more about the Nile Valley then the rest of the continent, which as much as I love Egypt as I'm a Pan Africanist I do claim it as apart of Africa's history but people hyper focus on it too much and ignore much more interesting African civilizations and cultures Imo, such as Kush and Kerma or even Tichitt which you have done such a great job providing information on and gave me new knowledge I had no idea about. I feel as a Diaspora we need to tell our stories and not just the same old slavery narrative or colonialism but our rich diverse history it would be great to see tv shows and movies about Ancient Ghana and Axum or perhaps even Swahili civilization so much to draw from.