Mansa Musa and the royal pilgrimage tradition of west Africa: 11th-18th century

Why Africa's caravans of gold stopped travelling to Arabia.

The golden pilgrimage of Mansa Musa was a landmark event in west African history. Travelling 3,000 kilometers across Egypt and Arabia with a retinue of thousands carrying over a dozen tonnes of gold, the wealth of Mansa Musa left an indelible impression on many Arab and European writers who witnessed it and increased their knowledge about west Africa before the Atlantic era.

Mansa Musa's journey was part of a royal pilgrimage tradition in west Africa that saw more than 20 sovereigns undertaking the perilous journey to Mecca while still in power. The objectives of these royal pilgrimages have confounded many, it's thought that their ostentatious displays of wealth were intended at attracting commercial attention; that their diplomatic exchanges were for gaining international recognition, and that the multiple journeys undertaken by some west African sovereigns were simply acts of piety. Equally confounding was why, after more than seven centuries, did the practice of Royal pilgrimages suddenly stop.

This article provides an overview of the royal pilgrimage tradition of west Africa, it looks at the evolution of the hajj as an important legitimating device in the internal political context of west Africa inorder to explain why it was eventually abandoned.

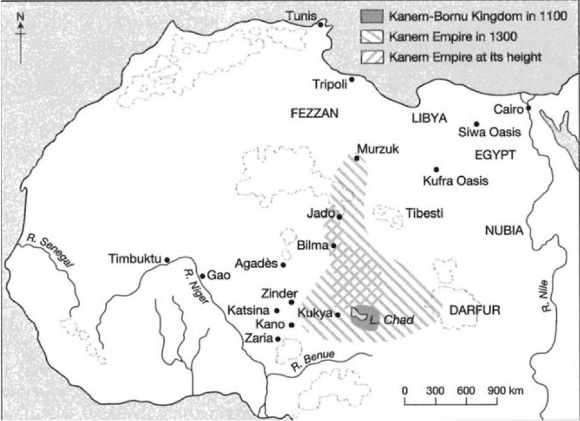

Map of Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage route in 13241

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

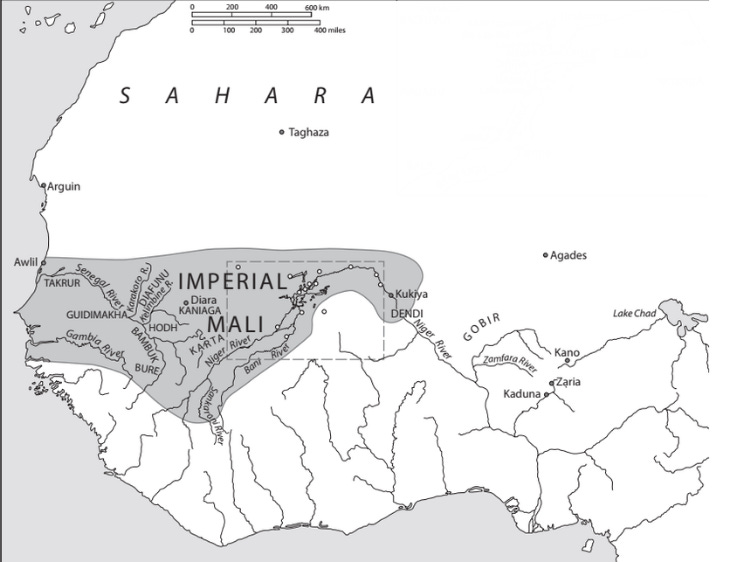

Before Mansa Musa; early royal pilgrimages from the empire of Kanem between the 11th-13th century.

West Africans, both royals and non-royals begun gradually adopting Islam in the late 10th century, and like all Muslims, accepted the major pillars of the religion which included the obligation to undertake the Hajj (pilgrimage to mecca). The pilgrimage to Mecca is simultaneously a religious, social, economic and political phenomenon, which has mobilized the faithful from all over West Africa. However, it was in the states of Mali, Songhai and Kanem-Bornu that the practice of this religious duty was most closely associated with the power and functioning of the state.2

While there are plenty of references to non-royal pilgrims from west Africa before the 13th century —especially from the Ghana empire— there are relatively few external sources documenting west African rulers making the journey themselves at this time; possibly because the act of pilgrimage hadn't yet acquired the political objective which it would later be associated with.

The earliest mention of a royal pilgrimage made by a west African sovereign comes from internal sources, with the first being of the ruler (Mai) of Kanem named Ḥummay (r.1075-1086) who was the founder of the empire’s Sefuwa dynasty. He is credited with the construction of a mosque in Cairo and is said to have died on his way back from pilgrimage. He was soon followed by his successor Dūnama b. Ḥummay (1086-1140) who may have made the pilgrimage thrice. Last among these early pilgrim kings was Mai Dūnama b. Salma (1210-1248) who likely performed a pilgrimage prior to the construction of a school in Cairo in 1242 meant to accommodate Kanem pilgrims and scholars.3

The Kanem sultans' construction of schools and lodges for pilgrims and students, which would be emulated by later rulers, was a long-term investment in favor of pilgrims coming from the Lake Chad region, providing the necessary infrastructure to allow the sultans to benefit from local relays and facilitating the logistics of the pilgrimage and scholarship.4 Unlike later pilgrimages however, these three early royal hajjs from west Africa are only mentioned in local documents written centuries after the event, but corroboration by external sources only begins in the 13th century. One early royal pilgrimage attested in external accounts was made by a minor mande ruler named Barmandana who according to Ibn Khaldun and al-Maqrizi, performed the hajj prior to the flourishing of the Mali empire's founder Sunjata keita.5

Map of the Kanem empire in the early 2nd millennium

The Age of Imperial Mali and Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage :14th century

The establishment of a Royal pilgrimage tradition in Mali is tied to the foundation of the empire as recounted in the "sunjata epic" about the first ruler (Mansa) of Mali; Sunjata keita. A central theme in the Sunjata epic is his banishment and subsequent movement from kingdom to kingdom (including to the historic capitals of Ghana and Mema), establishing an arterial network of alliances.6 This tradition was likely influenced by a tradition in Mande-speaking groups in which hunters enter the wilderness for considerable periods to learn their craft and survivability, as well as to harness occult power from defined spaces that together constitute a "sacred geography".7

Using the alliances he had created in exile including the cavalry from Ghana and Mema and the hunters from various Mande polities, Sunjata defeats the armies of Sumaoro, who had taken over the collapsed empire of Ghana. Sunjata, who took on the title Mansa, then establishes the core of the Mali empire through a combination of diplomacy and war. He creates Mali's “Grand Council” or “General Assembly” led by lineage heads and generals from the allied states.8 At this point, while Islam was present in Ghana and a few mande states, the religion was on the periphery of Mali's society which was still dominated by the non-Islamic hunter cults whose adherents featured prominently in Mali's political structure.9

In the period after Sunjata's death, a succession conflict pitted the gradually Islamizing council against the hunter guilds, in which the latter's power was eroded and led to the succession of three muslim Mansas; Ulī, Wātī and Khalīfa. These three Mansas are all said to have been sons of Sunjata, but even more importantly, according to Ibn Khaldūn, Mansā Ulī undertook a pilgrimage during the reign of the Mamluk sultan al-Ẓāhir Baybars sometime between 1260 and 1277. "This Mansa Uli", says Ibn Khaldun, "was one of their greatest kings", and he initiated Mali's northward expansion to Walata and Timbuktu that later would be completed by his later successors.10

Map of the Mali empire at its height in the late 13th century

Mansa Ulī's pilgrimage, the first of its kind for a Mali emperor, was created in the context of internal political rivalry and contested legitimacy. The hajj was transformed into a cultural signifier; combining Mali's pre-Islamic traditions of hunter-journeys to appropriate spiritual power from sacred spaces, with the Islamic obligation of pilgrimage to mecca which takes the pilgrim through the sacred places of Mecca and Medina and gives the pilgrim a spiritual blessing (baraka).11 The same internal political rivalry led to the pilgrimage undertaken by Mansa Sākūra in the late 13th century. Sākūra was reportedly a former royal slave that ascended to the throne with support from the council and other important political figures. He came to power after Mansa Khalīfa's courtiers had deposed him infavour of the short-lived boy-king Abu Bakr, when Khalīfa's reign was considered tyrannical. Sākūra is credited with expanding the empire eastwards to the city of Gao, and the description of his accomplishments in external sources bears a striking resemblance with Mansa Mûsâ.12

Sākūra went on pilgrimage in 1298, visiting Cairo in the reign of the Mamluk sultan al-Malik al-Nasir b. Qala'un, but is said to have died on the route back from his pilgrimage and he was immediately succeeded by Mansa Qū who was inturn succeed by his son Mansa Muḥammad Qū13. These two rather obscure Mansas, whose relationship with Sākūra are unclear, were unanimously known in tradition as direct descendants of Sunjata unlike Sākūra. It is Mansa Muḥammad Qū who is the subject of a fascinating account about an ambitious voyage across the Atlantic that was recounted by his successor Mansa Mûsâ during the latter's pilgrimage.14

"We belong to a family in which power is inherited. He who was [king] before me did not believe that the ocean was impossible to cross. He wanted to achieve his extremity and was passionate about this project. He equipped 200 boats which were full of men and as many who were filled with gold, water and provisions, enough to face several years. He then said to those who were in charge of these boats: "Do not come back only after you have reached the end of the ocean or if you have exhausted your provisions or your water". They left. Their absence was prolonged. None returned while long periods were flowing. Finally, a boat returned, only one. We asked the chief about what they had seen and learned. “Gladly, O Sultan,” he replied. "We have traveled a long time until the moment when a river with a violent current appeared in the open sea. I was in the last of the boats. The others came forward and when they were in this place, they did not were able to return and disappeared. We don't know what happened to them. Me, I came back from this place there without committing myself to this river". The sultan rejected his explanation. He had subsequently 2000 boats, 1000 for himself and his men and 1000 for water and provisions. Then he installed me as his replacement, embarked with his companions on the ocean and left. That was the last we saw of him and all those who were with him, and so I became king in my own right" .15

This introduction makes it clear that this was a story about the transmission of power, in which Mûsâ's predecessor attempted an exceptionally ambitious undertaking to legitimate his power (even more grandiose than the hunter journeys and pilgrimages of his predecessors) but ultimately failed to return (just like Sākūra) thus justifying Mûsâ's ascent to the throne. “Mûsâ's account of the circumstances of his accession to power is perhaps not to be understood as the somewhat off-topic narration of a failed maritime adventure on the part of his predecessor, but as the argumentation of his own legitimacy to rule".16 Its in this context that the famous Mansa undertook his own lavish pilgrimage through the Holy places of Islam, undoubtedly with the same purpose of internal political legitimation as his predecessor, but unlike the ill-fated Atlantic adventure, Mansa Mûsâ succeeded in returning to Mali.

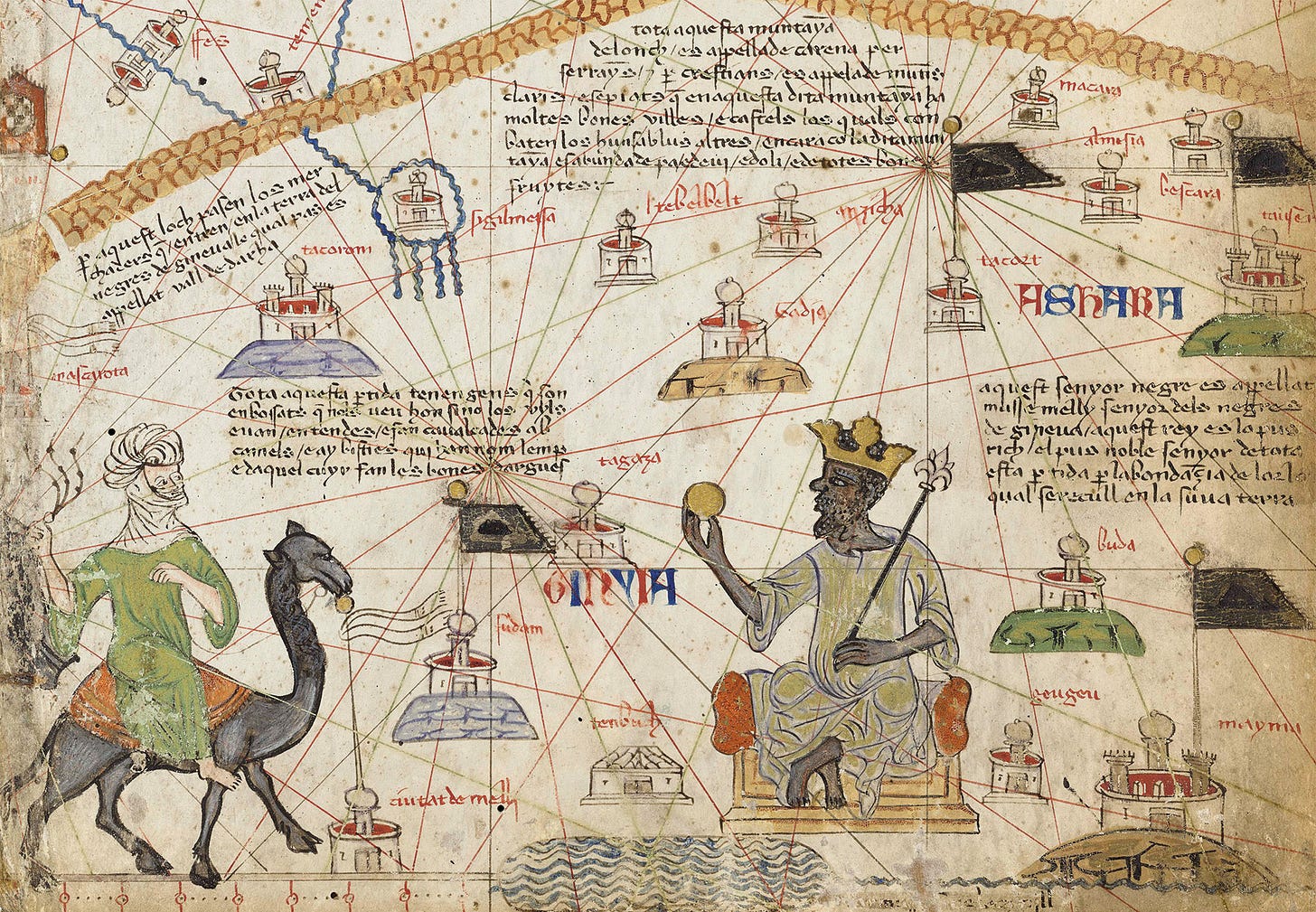

Mansa Mûsâ had ascended to the throne of Mali in 1312. Unlike Muḥammad Qū and his father, Mûsâ came from the line of Sunjata’s younger brother Manden Bukari, and the switch from Sunjata's lineage to Bukari's doubtlessly raised questions of legitimacy throughout his early reign and likely influenced the decision to undertake a pilgrimage —just as his predecessors Ulī and Sākūra had done when faced with challenges to their own legitimacy—. Mansa Mûsâ embarked on a pilgrimage in the twelfth year of his reign, arriving in Cairo in 18 July 1324. The number of people accompanying the Mansa on his pilgrimage (8,000-60,000), the amount of the gold they carried (8-12 tonnes), the places they visited, and the dozens of traders and scholars who witnessed and recorded Mûsâ's pilgrimage need not be rehearsed here for the sake of brevity.

Detail from the Catalan Atlas, ca. 1375, showing Mansa musa holding a golden nugget

What's more relevant is the extravagance of the pilgrimage which not only outdid the ambitious Atlantic voyage of Mansa Muhammad, but also earned him external legitimacy from other Muslim powers in a way that utilized an already established tradition17. Mansa Mûsâ acquired the baraka of the ḥajj, was invested with external political currency from his association with the Mamluk sultan al-Nāṣir, and was accompanied by several scholars including "jurists of the Malikite school” whom he brought on his return to Mali. He arrived in 1326 through the cities of Gao and Timbuktu that had been subsumed into the empire during his absence.18

Claims that Mansa Mûsâ's foreign companions introduced many innovations from the Islamic mainland are exaggerated --for example, the Friday mosque at Timbuktu was only the latest in a very old architectural tradition that was already attested at Gao, Djenne and Kumbi Saleh more than five centuries prior19, and the Maliki school was well established in the cities of Dia-Zāgha, Kābara and Djenne during the Almoravid period, centuries before scholars from these cities moved to Timbuktu.20 Even more importantly, the Arab companion that Mansa Musa came with from Egypt (called Abd alRahman) found his knowledge of Maliki jurisprudence to be less than that of the scholars of Timbuktu and was forced to move to Fez for further studies21, Showing that scholarly communities in Mali were not in need of a generous patron like Mansa Musa, nor was his famous Hajj necessary for the Timbuktu scholars to collaborate with their peers in Fez (Morocco).

Nevertheless, the pilgrimage greatly augmented Mali's Islamic credentials externally, such that barely two decades after Mûsâ's pilgrimage, the famous globe trotter Ibn Baṭṭūṭa was inclined to visit it in 1352 (possibly on a diplomatic mission), and described what was then an entirely Muslim country. The recognition acquired from Mali's external Muslim peers had rewarded it with regular diplomatic contacts such as with the Marinid sultanate of Morocco and Algeria, without the need for sub-ordination, since the Mansas were recognized as the sole and paramount rulers in Mali.22

The Royal Pilgrimage tradition of Mali ended with Mansa Mûsâ, and none of the succeeding Mansas of the remaining three centuries undertook a pilgrimage (despite the increase in non-royal pilgrimages by west African scholars), perhaps an indication that its usefulness as an internal legitimating device had been exhausted.

Djinguereber Mosque in Timbuktu, the original structure was commissioned by Mansa Musa but was greatly modified during the succeeding centuries

The institutionalization of the Royal Pilgrimage tradition in Kanem from the 14th-15th century

During the time when Mali's royal pilgrimages had been discontinued, the neighboring empire of Kanem continued the tradition of Royal pilgrimage, with many local records of Mais making the journey to mecca that were corroborated by external sources. The hajj of Mai Ibrāhīm b. Bīr (1296-1315), Mai Idrīs b. Ibrāhīm (1342-1366), and Mai 'Abdallāh b. 'Umar (1424-1431) are documented in endogenous and exogenous texts, with al-Maqrīzī mentioning the death of Mai 'Abdallāh on his way back from pilgrimage in 1432. More Kanem royal hajjs are mentioned in local sources including sultan Dāwud b. Ibrāhīm (1366-1376) , Bīr b. Idrīs (1389-1421) and Dūnama b. Bīr (1440-1444), although these three aren't corroborated in external sources.23

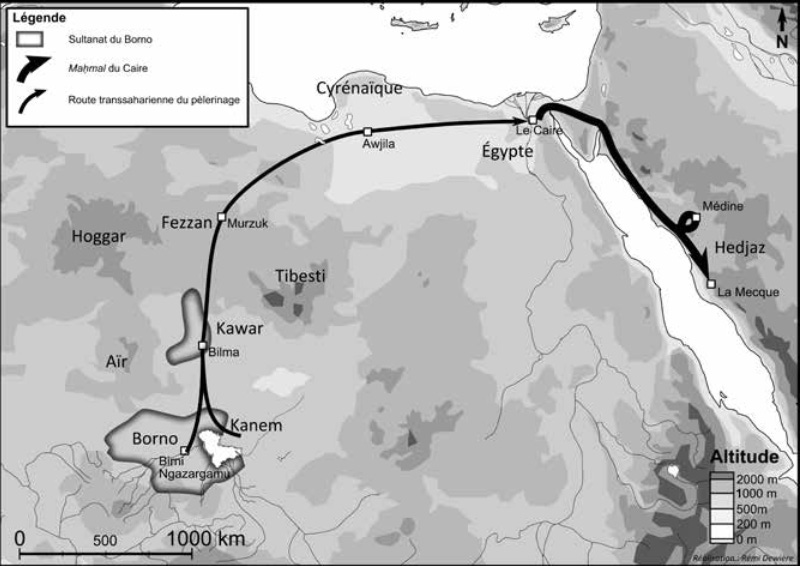

The 14th century was a period of internal political strife in the Kanem empire, in which an ideological and political conflict between the Islamized Sefuwa dynasty and the heterodox Bulala group led to a protracted war that divided the empire.24 Unlike Mali's internal political processes however, the royal pilgrimage tradition wasn't initially conceived as a tool for internal political legitimacy in Kanem, but was instead part of the prerogatives of the empire's sovereigns, who, through their protection (and later participation) in pilgrimage, demonstrated their ability to secure trade routes and ensure the safety their subjects who used them. It's in this context that the first diplomatic embassies were sent by the Kanem rulers to the rulers of Mamluk Egypt by way of hajj, with official envoys of the Mai often organizing and leading caravans to receive and respond to letters of assurances from the Mamluk sultans that guaranteed provisions and safety. These diplomatic exchanges eventually asserted the external legitimacy of the Kanem sovereigns with their external Muslim peers, further enhancing the standing of Kanem's rulers who begun using the title of Caliph/amīr al-mū'minīn (Commander of the faithful) by 1391.25

Map showing the royal pilgrimage route from Kanem-Bornu to Mecca26

The Royal Pilgrimage tradition After Mansa Musa: the Age of imperial Songhai and Askiya Muhammad in the 16th century

West Africa underwent a period of major political transformation beginning in the mid-14th century which ended with the establishment of the largest territorial states in its history. The weakening empire of Mali withdrew from its eastern provinces centered at Timbuktu and Gao, with the former being briefly falling under the Tuareg before it was conquered by the breakaway dynasty at Gao led by Sunni ‘Alī who established the empire of Songhai. Further eastwards, the breakaway of Kanem empire’s eastern provinces forced the Mais to establish a new state at Bornu, which rapidly expanded southwards into the Hausalands and northwards into the Kawar and Fezzan region. The Royal pilgrimage tradition of Kanem continued in earnest with the establishment of the Bornu empire, and from 1465 to 1696, between 7 and 9 Mais made or attempted to make the pilgrimage out of a total of 15.

Moving back to the western regions, the territory formerly dominated by Mali was quickly falling under Songhai’s control. But unlike Mali's complex process of subsuming distant polities, Sunni ‘Alī's Songhai relied almost exclusively on conquest through warfare and earned him a rather negative reputation among the scholarly community of Timbuktu and Djenne whom he exiled. After Sunni ‘Alī's passing in 1492, his army chose Abū Bakr Dā’u as the next emperor of Songhai, but this was opposed by Muḥammad Ture a high ranking official who raised his forces against the new emperor and defeated him in 1493. Muḥammad Ture then established the Askiya dynasty of Songhai but his rebellion against the deposed Sunni dynasty had little support from the political elites; with his only support coming from the urban scholarly community, which he immediately restored before moving across the empire and replacing its administration with loyalists.27

It's in this context of political rivalry and legitimation that the Askiya made preparations for pilgrimage, setting off for mecca in 1496. While the Askiya travelled with a smaller retinue compared to Mansa Musa's it was nevertheless fairly large; with a force comprised of 1,500 infantry and 500 cavalry, that carried some 300,000 mithqals of gold (about 1.4 tones). More importantly, the Askiya's companions included “a group of leaders from every community” that supported his new regime as part of his strategy of establishing a new administration loyal to him.28

The Askiya made charitable contributions in Mecca and Medina totaling 100,000 mithqals, and while in Medina he spent another 100,000 mithqals on the purchase of gardens which he converted into an “endowment for the people of Takrūr” and another 100,000 mithqals for his own personal trading in Cairo (just like the Mais of Kanem had done). And like Mansa Musa, the Askiya received external political legitimacy from other Muslim powers when he was symbolically anointed as the khalīfa of Songhay by the Abbasid caliph of Cairo to serve as the latter's regent29. This anointment had no real political consequences but imbued the Askiya with a religious/spiritual authority as Caliph/amīr al-mu’minīn, which further justified his usurpation of power and proved to be a powerful weapon against opposing elites in Songhai. Many of his companions were granted offices in the new administration.30

The success of the legitimation of Askiya Muhammad's rule through pilgrimage -among other legitimating devices- can be seen in the unchallenged hold on power that his dynasty enjoyed right up to the fall of Songhai in 1591. Future Askiyas utilized the administrative structures established by Askiya Muhammad to maintain their power and the succession process being largely determined by support of the military (just like the Sunnis) without the need for the perilous journey to mecca. Importantly, the Caliphal title played a major role in the conflict between Songhai and Bornu over suzerainty in the Hausalands, with both empires attempting to justify either's expansion by appealing to rival scholars al-Maġīlī (1425-1505) and al-Suyūṭī (1445-1505) to affirm themselves ideologically.31

After Aksiya Muhammad, none of the Songhai emperors saw the need for making the Hajj, despite the continued stream of non-royal pilgrims from west Africa that arrived in mecca and enjoyed the facilities left by the Askiya. The royal pilgrimage tradition in Songhai ended with him.

Map showing Imperial Songhai at its height in the early 16th century

The peak and decline of the Royal pilgrimage tradition in Bornu: 1484-1696

By the late 15th century, the Royal pilgrimages of Bornu had been transformed beyond their initial function of protecting outbound caravans. The visit of Mai 'Ali Ġāǧī (r. 1465-1497) in Cairo in 1484, within the framework of the pilgrimage, in order to obtain the investiture of the Abbassid caliph al-Mutawwakil II, marked a significant shift in the objective of pilgrimage. 'Ali Ġāǧī's example was followed by Mai Idris Alooma (r. 1564-1596) who made the pilgrimage to Mecca in 1565 to acquire sufficient internal political and religious legitimacy against an opposing dynastic branch32. Idris reportedly spent 220,000 mithqals of gold (about 1 tonne) purchasing goods in Cairo, and further confirmed his authority within Bornu by appointing his companions on the hajj in his administration, and declaring war against rebels who were supported by the rival dynastic branch. 33

In both cases, pilgrimage became an internal device for legitimation to reform the administration of the state, much like Askiya Muhammad, but also had an economic dimension by augmenting the already established external trade with Mamluk Egypt. This trade dimension to the hajj was particularly recurrent in Bornu, where another ruler; the Mai 'Alī b. 'Umar (r. 1639-1677) is also recorded bringing gold with him to spend in Cairo in 1648 during his pilgrimage there.34

Trade was doubtless part of the objective of the Bornu royal pilgrimages since the Kanem era. For example, diplomatic relations between the Pasha of Tripoli, Muḥammad Saqīzlī and Mai 'Alī b. 'Umar (r. 1639-1677) broke down for 5 years from 1648 to 1653 after the former attempted to monopolize trade with the latter on a right of first refusal basis. But since Bornu's economy was largely agro-pastoral and much less dependent on external trade than Tripoli, Mai 'Alī imposed a trade embargo on Tripoli and re-directed all external trade to Cairo, he also personally lead the different pilgrimage-caravans in 1642, 1648 and 1656, 1677 (performing the most pilgrimages of any west African ruler)35.

The Pasha Saqīzlī sent envoys to the Bornu sultan but the latter refused to change his policy, leading Saqīzlī to attack the Bornu caravan with its emperor on its return in 1478. The attack was a failure, Saqīzlī was killed by his finance director (likely because trade had collapsed) and his successor pasha 'Uṯmān Saqīzlī immediately sent envoys to Bornu and restore the old trading agreement that was in place before his predecessor. By 1653, the Sultan of Bornu is recorded sending porcelains to the pasha of Tripoli as trade relations had been resumed.36

Purchases made with gold weren't just aimed at increasing external trade, but also for securing the provisions and safety of the Bornu sultan's subjects abroad, following a custom established by the very first Kanem sovereigns. The 16th century Bornu chronicler Aḥmad Furṭū writes about the purchase of a palm grove in Medina by Mai Idris, which was populated by those who had accompanied him on his hajj. Other external sources also describe purchases made by the abovementioned 17th century Mai 'Alī b. 'Umar, who bought houses in Cairo, Medina and Mecca in order to lodge pilgrims and also acquired stores to meet the costs of the houses.37

The tradition of establishing lodges along pilgrim routes grew out of a local institution in Kanem-Bornu of controlling mobile populations.38 Many pilgrim villages/communities were also established in the eastern neighbors of Bornu especially in the territory of Darfur between the 16th and 19th century, a period which coincided with the gradual shift in the region trade and pilgrimage from northern routes to the eastern routes39 even though none of the Mais ever used that route. Many of these pilgrims from Bornu may not have completed the journey to mecca but opted to settle locally and were regarded as saints/holy-men; being credited with the foundation of many scholarly communities and zāwiyas (lodges). Migrations increased to the extent that upto 10% of northern Sudan's population in the early 20th century came from western Chad40.

The stream of Bornu pilgrims enhanced the Mai's regional legitimacy among his peers with one of Bornu's neighboring sultans in the kingdom of Darfur saying "the only true sultans were those of Borno and Constantinople".41 The circulation of scholars between Bornu and Egypt greatly increased during this period partly due to the royal pilgrimages (as well as the non-royal pilgrimages) During a pilgrimage to Mecca, Mai 'Ali Ġāǧī stopped in Cairo to consult with al-Suyūṭī, who reports that “they studied with [him] a certain number of [his] works, more than twenty, […] and other works".42

The intellectual exchanges between Bornu and Egypt occurred during a period of great intellectual debate in the Bornu capital about the origin of its ruling Sefuwa dynasty, which, like many Muslim dynasties, had initially claimed superficial prestigious origins from the Himyarite king of Yemen Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan who was important in early Islamic traditions. This superficial genealogy marked out the Kanem rulers as true Muslims in a region that was at the time still considered predominantly non-Muslim in external literature.43 But the abovementioned conflict between the now multiple Muslim dynasties of west africa (especially with the Askiyas who were now also considered Caliphs) forced the Sefuwa of Bornu to seek even more prestigious superficial genealogies. Beginning with the monumental work of Aḥmad b. Furṭū on Bornu's history in the 16th century, the Himyarite genealogy was combined with the Quraysh genealogy (from which the prophet Muhammad originated), placing the Bornu sultans at the same level as their rivals; the Ottomans and Moroccans, and above their west African peers. Claims of Quraysh descent were universally coldly received whether they were made by Ottomans or Moroccans, and it was no different in Bornu. But the frequent royal pilgrimages of the Kanem rulers greatly transformed the image of the hajj; especially given that the Quraysh tribe's direct association with Mecca and Medina, which now made it appear that the Bornu rulers who went there on pilgrimage were simply returning to the homeland of their ancestors.44

The royal pilgrimage in Bornu therefore acquired a multidimensional objective that was political, economic and religious, but more importantly, it was largely situated in the local and regional context based on evolving and overlapping practices of political legitimacy of Bornu, and its these practices that explain why it was eventually abandoned.

Map of the Bornu empire in the 17th-18th century.45

The end of the Royal pilgrimage tradition: Sokoto and west Africa’s age of revolutions in the 19th century

The 17th century saw the appearance of another practice of legitimization of the power of the Mais of Bornu: that of mysticism and personal charisma which directly competed with and eventually displaced the practices based on prestigious genealogies and enforced by the royal Hajj. This new practice had been been utilized by the most prolific hajji of all the Bornu rulers; Mai 'Alī b. 'Umar (1639-1677), whose mystical aura was such that according to an external writer; the Pasha of Tripoli "feared that the Arabs would take the opportunity to revolt against him, seeing in their country a king, African and who lived in the opinion of holiness among the Muslims".46

But just like the previous traditions utilizing the Caliphal title and the Quraysh descent that were also appropriated by neighboring kingdoms like Wadai and DarFur47, and the royal pilgrimages that were nearly adopted by the neighboring kingdom of Bagirmi and Kano48, the dialectic of power around mysticism in Bornu couldn't be monopolized by the Sefuwa sultans, as it was also appropriated and successfully used against them by Bornu's many vassals who utilized the new legitimating device to break off from Bornu's suzerainty when the latter was weakening.49

By the 18th century, the usefulness of the pilgrimage as an internal legitimating device had been exhausted, the last external record of a Bornu sultan making the hajj was in 1696 by Mai Idrīs b. 'Alī (r. 1677-1696)50. He passed away on his return trip from mecca in the Fezzan region of southern Libya, and was buried in the ancient Kanem provincial capital of Traghen where his whitewashed tomb became a minor pilgrimage site.51 While at least three more Mais are said to have performed the Hajj in the early 18th century especially Mai Ḥamdūn (1715-1729) who also studied in Cairo52, their pilgrimages weren't corroborated in external sources.53

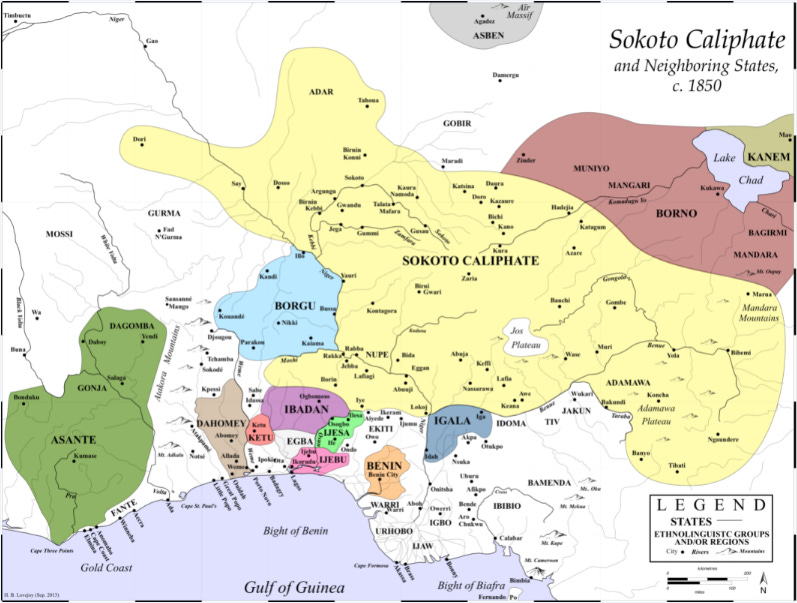

From the 18th to 19th century, West Africa's political landscape was transformed in a political revolution that saw the emergence of "theocratic" states such as Sokoto, Massina and Futa Toro, that were established by a highly learned scholarly class that sought to create an orthodox Islamic administration. Paradoxically, none of these theocratic leaders ever performed the obligatory hajj54, and while they acknowledged its religious relevance, they claimed they could not perform the Hajj due to their political positions. The theocratic elite went to great lengths to guarantee the safety of non-royal west African pilgrims, and the the Hajj caravans became specialized and institutionalized with chiefs, supervisors, heads of caravan subgroups, resting stations and military escorts.55

As a legitimating device, the Hajj had by then completely lost its political relevance, the theocratic elite performed the pilgrimage mentally through wanderlust literature, and just like in Bornu; mysticism and personal charisma became the main legitimating devices of an ideal leader in Sokoto; beginning with its founder Uthman Fodio.56

“They say that I have been to Mecca and Medina, and they have no doubt about it, These qualities are attributed to me by many people, and I must say they are wrong.”

Uthman dan Fodio, tahdhir al-ikhwan, ca. 1811, Sokoto.

Map of the Sokoto empire.

Conclusion: the function of west Africa’s royal Hajj in African history.

Far from being an ambitious quest for international recognition, the Royal pilgrimage tradition was a uniquely west African institution that served a mostly internal objective. West African states like Mali, Songhai and Bornu developed a set of discourses and customs in order to consolidate their authority and legitimacy regionally and later internationally. The obligatory hajj to mecca was adopted by west African royals as the powerful legitimating device especially during times when their internal legitimacy was contested and when they wanted to demonstrate their regional authority. Its adoption transformed and complemented pre-existing customs inorder to create a unique Royal pilgrimage tradition which became an established institution in the region.

The Royal Hajj evolved with time to become a potent external legitimating device, it was turned into an important commercial exercise involving cross-cultural diplomatic and intellectual exchanges in which west African Muslim states were fully recognized as independent powers led by Caliphs. The Royal Hajj was however not the only lever of legitimacy used by the west African royals, and overtime other legitimating devices were borrowed from several registers such that the pilgrimage tradition was eventually abandoned by west African sovereigns despite their increased commitment to the religion.

The brilliant theater that was Mansa Musa's pilgrimage and other west African kings who went after him was therefore not primarily intended for the foreign audience which it impressed but for the local audience from whom the kings drew their power.

March of a caravan out of Cairo to Mecca, ca 1700, (British museum 1982,U.1593)

The Mali empire was instrumental in preventing the early colonization of west Africa during the Atlantic era, read about its diplomatic and military encounters with Portugal on Patreon;

If you liked this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal

Map by Juan Hernandez

Islamic Scholarship in Africa by Ousmane Oumar Kane pg 94-96

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 223, 249, The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3, pg 325

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 250)

Beyond Timbuktu By Ousmane Kane, In Search of Sunjata by Ralph A. Austen pg 48)

In Search of Sunjata: The Mande Oral Epic as History, Literature and Performance by Ralph A. Austen pg 20

In Search of Sunjata by Ralph A. Austen pg 19 African dominion by Michael Gomez pg 77-79)

African dominion by Michael Gomez pg 82, 84, 87)

African dominion by Michael Gomez 94)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3 pg 379

African dominion by Michael Gomez pg 97)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3 pg 380

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3 pg 380

African dominion by Michael Gomez pg 100)

Le Mali et la mer (XIVe siècle) by François-Xavier Fauvelle pg 3-4)

Le Mali et la mer (XIVe siècle) by François-Xavier Fauvelle pg 5-11

The Course of Islam in Africa by M. Hiskett pg 94,99)

African dominion by Michael Gomez pg 121-125)

Historic Mosques in Sub-Saharan Africa pg 107-8

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg xxviii n19

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 73-74

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3 pg 394-5, African dominion by Michael Gomez pg 145-146-7, 155-158)

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 224)

History Of Islam In Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 80

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 246-249, 319)

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 233

African dominion by Michael Gomez pg 221-226)

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by J. Hunwick pg 103-104

History Of Islam In Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 70, Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by J. Hunwick pg 105

African dominion by Michael Gomez pg 234-235, 246-247)

Kano relations with Borno : early times to c. 1800 by Bawuro M. Barkindo pg 155)

Royal Pilgrims from Takrūr According to ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jazīrī (12th–16th Century)by Collet Hadrien pg 193-194

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 31, 248-252)

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 224

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4, pg 94

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 36-38, The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4 pg 121-122

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 250)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 4, pg 59-62, Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 337-338

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 3 pg 237, Vol 4, pg 57

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 243-5

The Darfur Sultanate by (Rex Sean O'Fahey, pg 79)

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 55)

The Legend of the Seifuwa: a study in the origins of a tradition of origin by Abdullahi Smith pg 20)

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 315-320)

mapmaker; twitter handle @Gargaristan

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 320-322)

History Of Islam In Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 120

the only Hausa ruler of Kano who attempted a pilgrimage in 1649 was deposed after just 9 months, see The government in Kano by M.G. Smith pg 158

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 323-324, The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol 4 pg 133-4

the two hajjis of this region —the 18th century figures Abd al-Qadir of Bagirmi and al-Kanemi of Bornu— went on pilgrimage before they were rulers

Les lieux de sépulture by D Lange pg 156)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol 4 pg 96

Du lac Tchad à la Mecque by Rémi Dewière pg 225

only Al-Hajj 'Umar Tal of Tukulor performed the pilgrimage in 1828-31, but this was before he was a ruler

A Geography of Jihad by Stephanie Zehnle pg 198-219)

The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 5, pg 155-6, History Of Islam In Africa by Nehemia Levtzion pg 86

"During the time when Mali's royal pilgrimages had been discontinued, the neighboring empire of Kanem continued the tradition of Royal pilgrimage, with many local records of Mais making the journey to mecca that were collaborated by external sources...More Kanem royal hajjs are mentioned in local sources including sultan Dāwud b. Ibrāhīm (1366-1376) , Bīr b. Idrīs (1389-1421) and Dūnama b. Bīr (1440-1444), although these three aren't collaborated in external sources.23...While at least three more Mais are said to have performed the Hajj in the early 18th century especially Mai Ḥamdūn (1715-1729) who also studied in Cairo52, their pilgrimages weren't collaborated in external sources.53"

Shouldn't it be corroborated instead of "collaborated"in these three sentences?

Keep up the good work