Maritime trade, Shipbuilding and African sailors in the indian ocean: a complete history of East African seafaring

from Aksum to the Swahili coast

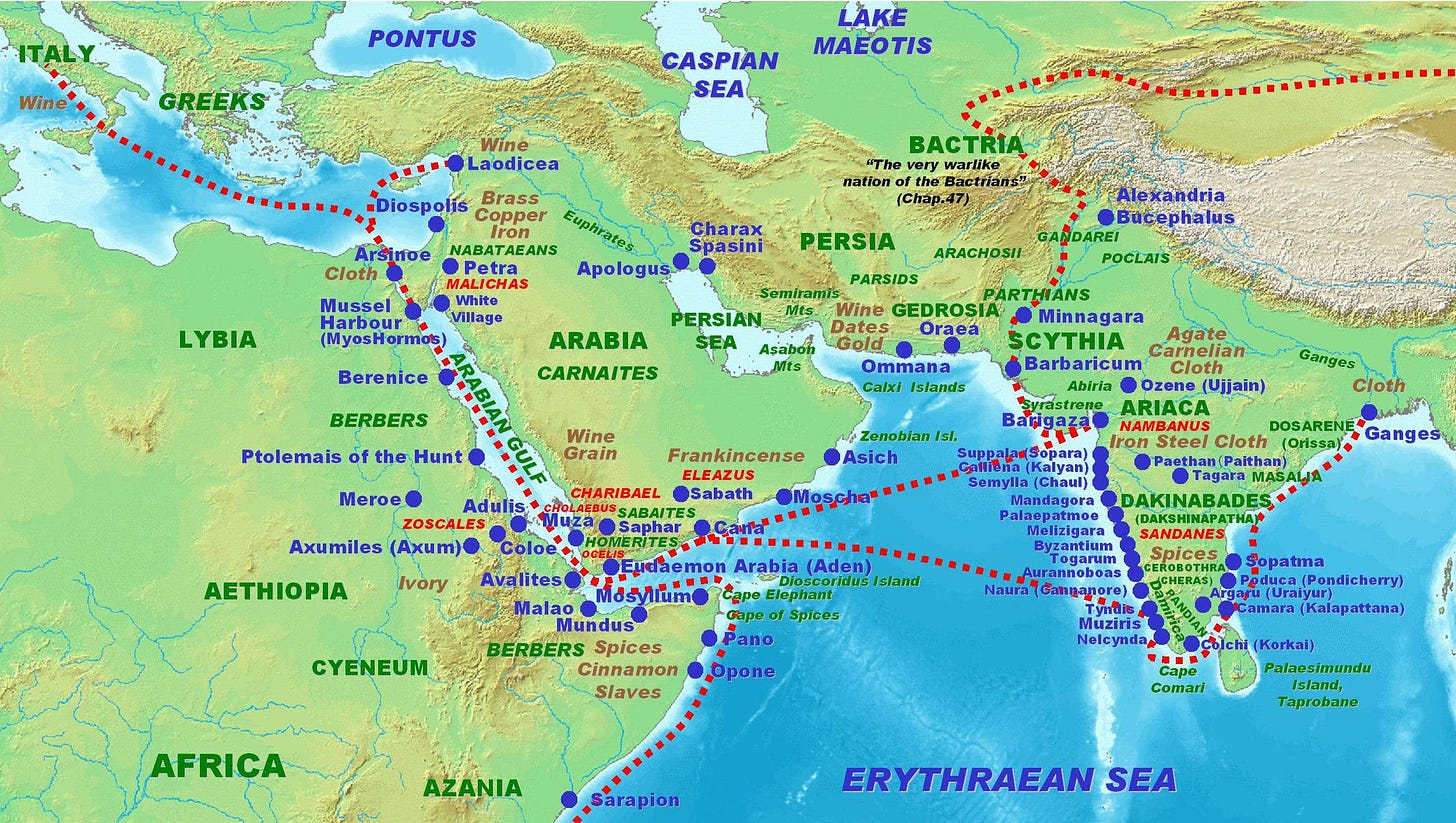

The Indian ocean world was the largest zone of cultural exchange and trade in the old world. Ancient maritime societies from south-china sea to the southeastern coast of Africa established a long chain of urban emporia that were closely linked through long-distance oceanic trade at their open ports, enabling the exchange of goods, ideas and people over a vast geographic space.

The eastern coast of Africa was intrinsically connected to the Indian ocean world, not just as the supplier of commodities but as the home of some of the world's most dynamic maritime societies. From the merchant-sailors from Aksum who played a significant role in the linking of the Mediterranean to the Indian ocean world, to the Swahili city-states which developed a maritime society with shipbuilding and voyages that directly linked the emporiums of southern Asia to the trading cities of east Africa.

This article explores the commercial history of the maritime societies along Africa's eastern coast from Sudan to Mozambique, including long distance voyages undertaken by African sailors, and shipbuilding in African coastal cities.

Trading ports and cities in the Indian ocean world 618-1500 by N. Chaudhuri

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Maritime trade in the northern half of the coast of Eastern-Africa

From Aksum to Sri Lanka: 1st-7th century

One of the most invaluable sources of Eastern Africa’s maritime history during the 1st century, was the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, an anonymously authored work composed between 40-50 CE. In its description of maritime activities within the redsea region, the Periplus mentions a vibrant regional trade between the port city of Adulis and the inhabitants of the Alalaiou islands (Dahlak Islands),1 as well as trade between the port city of Adulis and the Roman-Egyptian port of Berenike/Berenice. While the latter trade appears to have been largely undertaken by foreign sailors, there’s strong evidence that African merchants participated in it, if we take into account the archeological discoveries of a large Aksumite quarter at Berenice with Ge’ez inscriptions and Aksumite coins, that was very likely inhabited by wealthy Aksumite merchants.2

The involvement of African sailors in the red sea and Indian ocean trade received a further impetus after the replacement of direct navigation route from Roman-Egypt to India, with a multistage, transshipment route that stopped at Adulis beginning in the 2nd century, this often involved the transfer and/or exchange of Indian-derived cargo with African cargo and was mostly done by locally-owned ships and sailors.3

More impetus for Aksumite maritime activity was provided by the Aksumite conquest of Yemen in the 3rd century, which brought the competitors of Adulis under Aksumite control as well. The monumental royal inscription of the Aksumite king GDR in 200AD which mentions him sending “a fleet and land forces against the Arabitae and Cinaedocolpitae who dwelt on the other side of the Red Sea, and having reduced the sovereigns of both, I imposed on them a land tribute and charged them to make travelling safe both by sea and by land. I thus subdued the whole coast from Leuke Kome to the country of the Sabaean.” lends further support to the existence of a well developed maritime tradition in Aksum that was likely conducted through Adulis.4

It was during the height of the Aksumite empire that we find some of the most detailed description of of Aksumite merchants sailing in their own ships to Sri Lanka and the Persian gulf.5 A 6th century account by Cosmas Indicopleustes mentions that the roman sailor Sopatrus was travelling aboard a ship owned by "men from Adulis" who were Aksumite merchants most likely involved in the transshipment of Chinese silk and Indian pepper. Such commodities are described in other accounts of Aksumite maritime trade as being transshipped to the Jordanian port of Aila where 6th century writer Antoninus of Piacenza wrote that all the "shipping from Aksum and Yemen comes into the port at Aila, bringing a variety of spices".6

Aksumite empire’s greatest extent in the 4th to 6th century

trade in the western indian ocean during late antiquity

The African ports of the Red sea and Somaliland: 8th-19th century

Adulis and Aksum’s maritime activities vanish from external texts after the 7th century. Focus shifts to the cities of the southern red-sea cities of Zayla/Zeila (said to be under the control of Abyssinian Christians in 988) and the Dahlak archipelago, according to Al-Masudi's account from 935, which also describes a flourishing trade between the Aksumite state and Yemen although now almost entirely conducted by Yemeni merchants.7 The Dahlak archipelago, which had been settled by the Aksumites in the centuries prior to Aksum's decline, appears to have been the only large African polity in the red-sea region whose merchants were actively engaged in undertaking long distance voyages, and was important in the trade between Fatimid Egypt and India.8 There's however little documentation of direct voyages undertaken by Dhalak-based merchants outside the red sea, with one exceptional case about the exile to India of the Najahid sultan Jayyash (an Abyssinian of the Dahlak sultanate).9

After Dhalak’s decline in the 15th-16th century, African maritime trade was dominated by the red-sea port cities of Suakin and Massawa, and the city of Zeila in northern Somalia, especially the latter, whose merchants were actively involved in the western Indian ocean trade. Most long distance trade appears to have been in the hands of foreign merchants, with local vessels confined to regional trade and pearl diving, as one account describing the residents of suakin in the late 19th century noted that "they are skillful sailors, but very rarely go with the Arabians away from their own coast".10

Shipbuilding in the northern half of the coast of Eastern-Africa

Some information about shipbuilding during the Aksumite era is provided by 6th century external accounts. In a passage describing the Aksumite fleet of king Kaleb, the 6th century historian Procopius mentions that Aksumite ships "are not made in the same manner as are other ships (ie: from the Mediterranean). For neither are they smeared with pitch, nor with any other substance, nor indeed are the planks fastened together by iron nails going through and through, but they are bound together by a kind of cording"11 There’s evidence of the extensive use of sewn ships across the Indian ocean world in general and the African coastal societies in particular. The Blemmeye nomads on the frontier between Rome and Kush in southeastern Egypt were described as possessing a navy consisting of sewn ships, which was placed under a navarchos (admiral) .12

Shipbuilding on the Afrian half of the red-sea coast appears to have declined after the fall of Aksum, as none of the major port cities of Badi, Aydhab, Suakin, and Dahlak, are known to have been engaged in shipbuilding, despite Aydhab being described as "one of the most frequented ports of the world," by Ibn Jubayr (d.1217).13 In the account of his visit of Ethiopia in 1789, Jerónimo Lobbo mentions that the most common ships in the red sea were called 'Gelves', another type of medium sized sewn ship that was built locally using timber and other materials from the coconut-palm tree, but doesn't specify the main ports of its construction.14 Few descriptions of boat-building in Suakin and Massawa carried out along sections of beaches near the cities, using imported materials and expatriate craftsmen (gehanis) hired by local merchants.15

Most of the African-controlled long-distance maritime trade and shipbuilding activities along the Eastern African coast therefore appear to have been confined to its southern half; the Swahili coast.

Suakin beachfront in 1890 showing a medium sized ship and several others in the background

Suakin beachfront in 1883

Long-distance maritime trade along the southern coast of Eastern Africa

The "shore-folk" of the Swahili coast had for long been extensively involved in long-distance maritime trade since the emergence of the Swahili and Comorian city-states in the late 1st millennium. Wealthy patricians in city-states had financial interests in sea voyages beyond the East African waters, and some owned ships big enough to sail to the Arabian Sea and Southern Arabia. The ability of the Swahili to sail across the "Swahili corridor", transshipping trade goods from southern Mozambique to Southern Somalia, was one of the main features of the extensive maritime trading system that characterized the Swahili civilization.16

The indigenous innovation of sewn boats on the Swahili coast, which occurred largely within its local context without significant external influence, was central to the expansion of the Bantu-speaking groups of the Swahili and Comorian speakers across the east African coast and its offshore islands during the 1st millennium.17 One of the earliest mentions of watercraft along the southern half of the East-African coast comes from the Periplus of the Eythrueun Sea, which describes the the island of Menuthias (possibly Pemba or Unguja, or Mafa) that has “has sewn boats and dugout canoes that are used for fishing", it also describes similar vessels in the southernmost coastal town; Rhapta, whose name is derived from the name of the sewn boats (rhupton ploiurion).18

Evidence of regional maritime activity, which had been established around the turn of the common era, gradually increases in the late 1st millennium, and provided the impetus for long-distance maritime activities by the Swahili in the succeeding era.19 Long-distance maritime trade was thus an extension of the more robust regional transshipment trade between Swahili cities which dominated the region's maritime traffic as late as the 19th century. An account written in Mombasa in 1824-1826, which calculated the annual traffic of ships entering the Mombasa harbor, reveals that more than half of all ships (155 of 250) were locally built vessels confined to regional trade between the cities, and given their estimated capacity of 7,000 tonnes, compare favorably with the 600 tonnes of goods recorded to have been imported to Mombasa from Gujarat in 1776.20

Map of Swahili voyages in the western indian ocean

External accounts from Yemen indicate that, ships from Mogadishu made annual trips to the Hadrami ports of Aden, al-Shihr, among others, carrying various commodities such as ivory, grain, ambergris, wood, and gum copal that had been transshipped to Mogadishu or Barawa by local ships sent from southern Swahili port-cities, and another account from 1336, records the arrival of a a ship “from Kilwa,” loaded with rice, at the Hadrami city of Aden.21 In a 1441 account by al-Samarqandī, the scholar mentions that the trade of Hormuz involved merchants from Abyssinia, Socotra and the Land of the Zanj who sent their own traders and products to the city. Another account from 1341 by Ibn Batutta in Madayi ( northern Malabar) in 1341, mentions a “virtuous ulama” from Mogadishu named Saʿīd, who had travelled to india and china.22

Direct Swahili voyages to India would have begun not long after voyages to southern Arabia had been accomplished. In 1505, Tome Pires noted the presence of several eastern African merchants from Ethiopia, Mogadishu, Kilwa, Mombasa and Malindi in port of Malacca in Indonesia, although its unclear whether they had arrived aboard their own ships23. In 1517, the Malindi sultan sent a letter to his suzerain the king of Portugal, requesting a letter of protection from the latter to allow him free travel throughout the Portuguese possessions from Goa to Mozambique24, In 1586 the sultan of Malindi sent a ship to the Portuguese settlement of Bassein (India), and in the 1590s, the same sultan requested to acquire ships for trade to India and China and to ferry Swahili pilgrims to mecca, which were accepted. A 1619 account mentions traders from the Malindi coast visiting Goa, including one named Muhammad Mshuti Mapengo who was “well-known in Goa, where he often goes.”25

In 1631, the sultan of Pate sent a ship to Goa, and by the 1720s, the ivory trade was very active between the northern Swahili coast and Gujarat, with shipowners from Barawa/Brava used to send a shipment of ivory to Surat (India), and the sultan of Pate asked of the Portuguese the right to send “one of his ships” loaded with ivory to Diu, and asked for free circulation of their ships to “all the ports of Asia. In 1726, a letter from the king of Pate mentions a locally-born merchant named Bwana Madi bin Mwalimu Bakar from Pate “who goes each year to Surat where he is married.” In 1763, Carsten Niebuhr met in Bombay a “Sheikh” of the Lamu Archipelago, who had come to propose the British to buy cowry shells in “his small island.”26

13th-16th century Ship graffiti from Kilwa kisiwani and Songo mnara

Direct voyages by the Swahili to India had likely declined by the late 18th century as an account by Jean-Vincent Morice in 1777 observed that the Swahili were then not rich enough to own ships made for trips to Gujarat; but that they still built large ships to sail as far as Muscat (Oman), and according to Morice in the 1770s, the Swahili would also board with their own cargoes onto Arab or Gujarati ships to reach Surat. 27

Direct trade by local sailors from the east African coast to southern Arabia on locally-owned ships continued in the 18th and 19th century, especially from the city of Mogadishu, which was the primary outlet for the extensive grain trade from plantations based on the hinterland. Mogadishu's grain exports, which were estimated at over 3,000 tonnes in the 1870s, were carried in locally-built ships with a capacity of 50-200 tonnes, that according to an 1875 account by John Kirk were "all filled with or taking in native grain".28

The Swahili ship captain (and owner) was called nahodha, while the pilot was called mwalimu. East African waalimu and nahodha were often respected and learned men, whose nautical knowledge was based on extensive training and experience, which foreign crews entering East African waters were highly dependent on. In 1606, the Franciscan friars met a mwalimu from Pemba described explicitly as a Swahili "old Muslim negro", who in 1597 had guided the ship of Francisco da Gama, the future viceroy of India, from Mombasa to Goa29. In 1615, Thomas Roe met in Nzwani a Mogadishu-born Mwalimu (pilot) named Ibrahim who is described as an expert in navigation from “Mogadishu” to the Gulf of Cambay, he also owned an elaborate nautical chart of the western Indian ocean “lined and graduated orderly” and was able to correct the map used by the English30. While in the Kerimba islands in 1787, Saulnier de Mondevit took on board a Swahili pilot named Bwana Madi “who spoke French well and very much learned, as a pilot, of the African coast from Mozambique to Muscat.” Bwana Madi made a very precise map of the coast up to Zanzibar.31

In 1783, a prince of Nzwani described the island merchants’ circular trade which they carried out in “their own vessels” for raw cotton and firearms from Bombay (British India), which they then trade with other merchants in Madagascar, Mozambique and neighboring Comoros island, most of this trade continued relatively uninterrupted well into the 19th century.32

Ocean-going dhows in Mombasa (Old Port) Harbour, 1890-1939, Northwestern University

Zanzibar, Dhows in Harbor, 1880s, Northwestern University

Swahili Ship types and Ship construction.

The mtepe and dau la mtepe, both of which were of sewn construction, were the characteristic vessel of the East African coast that was almost exclusively owned by the local inhabitants of the coast. The mtepe’s versatility was poetically described by Burton in 1872 that it “swims the tide buoyantly as a sea-bird…and can go to windward of everything propelled by wind”. Despite their undifferentiated description in external accounts, these ships were of multiple varieties and their construction kept changing overtime.33 The mtepe, which is described in early accounts as mutepis, was a relatively old watercraft of local manufacture, its name likely derived from the itepe word for the coconut-palm cording that it uses. It had a square sail made of matting, and a prominent long curved prow, and a square transom at the stern.34

The dau la mtepe , which is described in early accounts as a dallos/dalles or a "real dhow". Despite earlier claims that the Swahili name for this ship; dau/įdalu, was a borrowed term acquired from the Arab-Indian dhow (dāw/ḍāu), the Swahili dau was infact a local derivation from the Proto-Swahili word ndalu that refers to water-bailers, and it was the Swahili dau which was the origin of the Arab-Indian dhow, the latter name being mostly used in external European accounts instead of the more accurate local names for Arab and Indian vessels.35 The dau la mtepe is slightly smaller than the mtepe, it has a normal type of raking stern, and the bow is straight and more angled than that of the mtepe with a thin bowsprit. The stern and stem were built up with a series of V-shaped hooks and, the ship was also steered using 16 oars and used a large wooden anchor.36

The majority of Swahili ships had a tonnage of 30-60 tons, with an average length of around 12-30 meters, an average width of 8m, a depth of 3m, a mast-height of 15-20 meters, and a combined passenger and crew total of 40-60 people, and its crewmen possessed compasses, quadrants, and maritime charts.37 . At low tide, ships could rest on the beach, supported by the keel and side stakes. They were of shallow draft and could navigate in extremely shallow waters.38

Illustration of a Mtepe by G.L sullivan, 1873, and an illustration of a Mtepe by Mark Horton based on a scale model from the 1930s

a Dau and Mtepe by Charles Guillain, 1853

Zanzibar beachfront in 1875 showing various types of ships including the single-mast mtepes and daus

Both Mtepes were primarily built in the Lamu archipelago, especially in the cities of Faza, Tikuni and Siyu. In Faza, 20 mitepe were made annually, possibly a total of about 100 a year for the whole archipelago not including other types of ships, this region is also where we first find the description of “mutepis” in an external account from 1661.39 The ability to build and to maintain large ships (which were repaired every four years), and to support their crew, was limited to the minority of the wealthy patricians. In Nzwani, the largest ships belonged to the governor and a captain named, Boomoodoy, the latter being described as an enterprising local trader who had financed their construction and had “knowledge in Oriental navigation", according to a 1704 account by John Pike.40

The last of the classic ocean-going Mtepe was built in Lamu during the 1930s before it was wrecked off the Kenyan coast in 1935, its skipper passed on in 1968, closing the chapter on an ancient tradition

Did WEST AFRICAN SAILORS discover the Americas before Columbus? Read about Mansa Muhammad's journey across the Atlantic in the 14th century, and an exploration of West Africa's maritime culture on Patreon

If you liked this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please support my writing via Paypal/Ko-fi

The foreign trade of the Aksumite port of Adulis by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 109)

The Indo-Roman Pepper Trade and the Muziris Papyrus by Federico De Romanis pg 55, The Red Sea during the 'Long' Late Antiquity by Timothy Power pg 61)

The Indo-Roman Pepper Trade and the Muziris Papyrus by Federico De Romanis pg 67-75)

The Red Sea during the 'Long' Late Antiquity by Timothy Power pg 31)

The foreign trade of the Aksumite port of Adulis by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 115)

The Red Sea during the 'Long' Late Antiquity by Timothy Power pg 125-128, 45-47)

The foreign trade of the Aksumite port of Adulis by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 120)

The Red Sea during the 'Long' Late Antiquity by Timothy Power pg 75, 296-297, )

A History of Chess: The Original 1913 Edition By H. J. R. Murray pg v

Desert and Water Gardens of the Red Sea by Cyril Crossland pg 59-65)

Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity by S. C Munro-Hay pg 220-222)

Military History of Late Rome Ilkka Syvänne pg 64

The Rashayda: Ethnic Identity and Dhow Activity in Suakin on the Red Sea Coast by Dionisius A. Agius pg 195-196

A Voyage to Abyssinia By Jerónimo Lobo pg 46-47

Africa and the Sea by Jeffrey C. Stone pg 111

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet 169-170)

From dugouts to double outriggers by Martin Walsh pg 286)

The Mtepe: regional trade and the late survival of sewn ships in East African waters by Erik Gilbert pg 297, From dugouts to double outriggers by Martin Walsh pg 260)

When Did the Swahili Become Maritime? A Reply by Elgidius B. Ichumbaki

The Mtepe of Lamu, Mombasa and the Zanzibar Sea by AHJ Prins pg 88-89, East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 187

When Did the Swahili Become Maritime by J. Fleisher pg 107

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 188)

The Suma oriental of Tome Pires by Tomé Pires pg 46

A Handful of Swahili Coast Letters, 1500–1520 by Sanjay Subrahmanyam pg 270-271

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 185

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet 185, 188 )

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet 183, 187)

Exploring the Old Stone Town of Mogadishu pg 8-9

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 184)

L’Afrique orientale et l’océan Indien by Thomas Vernet and Philippe Beaujard pg 178

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 178)

The Comoro Islands by Malyn D Newitt pg 20

The Mtepe of Lamu, Mombasa and the Zanzibar Sea by AHJ Prins pg 88)

From dugouts to double outriggers by Martin Walsh pg 268, The Mtepe: regional trade and the late survival of sewn ships in East African waters by Erik Gilbert pg 276)

From dugouts to double outriggers by Martin Walsh pg 265-266)

The Mtepe: regional trade and the late survival of sewn ships in East African waters by Erik Gilbert pg 297, The Mtepe of Lamu, Mombasa and the Zanzibar Sea by AHJ Prins pg 89)

The Mtepe of Lamu, Mombasa and the Zanzibar Sea by AHJ Prins , East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 176-177)

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 175-176, Seascape and Sailing Ships of the Swahili Shores by R de Leeuwe pg 11)

The Mtepe: regional trade and the late survival of sewn ships in East African waters by Erik Gilbert pg 298, Seascape and Sailing Ships of the Swahili Shores by R de Leeuwe pg 11)

East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean by Thomas Vernet pg 186)