Megalithic Landscapes of Ethiopia from Prehistory to the Modern Era

Ethiopia is home to one of the largest concentrations of megalithic architecture globally.

In contrast to the majority of prehistoric megalithic traditions that survive only as archaeological remains, the construction of stelae in Ethiopia isn’t a relic of the forgotten past, as the country is one of the few places in the world where the erection of stone monuments has continued into the historical and modern eras.

The megalithic culture in Ethiopia encompasses a wide range of forms, including standing stones (stelae), dolmens, and tumuli. These monuments are widely distributed across the landscape, with hundreds of sites documented in northern, central, and southern regions of the country.

Among the most renowned examples are the famous obelisks of Aksum, the prehistoric dolmens of Harar, and the enigmatic stelae of Tiya, whose carved surfaces are profusely decorated with symbolic and figurative motifs.

This article outlines the history of the Ethiopian megaliths from the prehistoric period to the modern era.

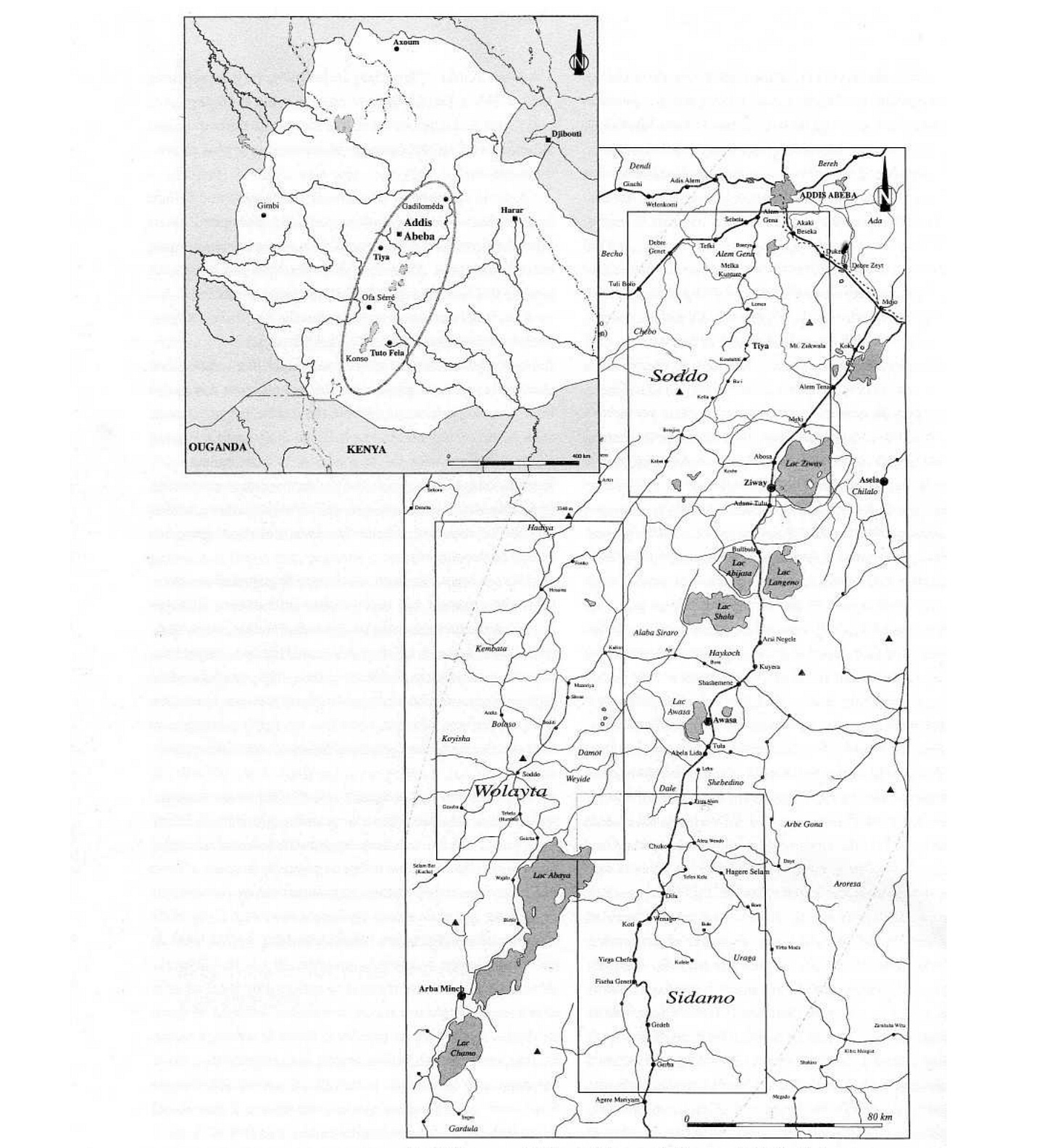

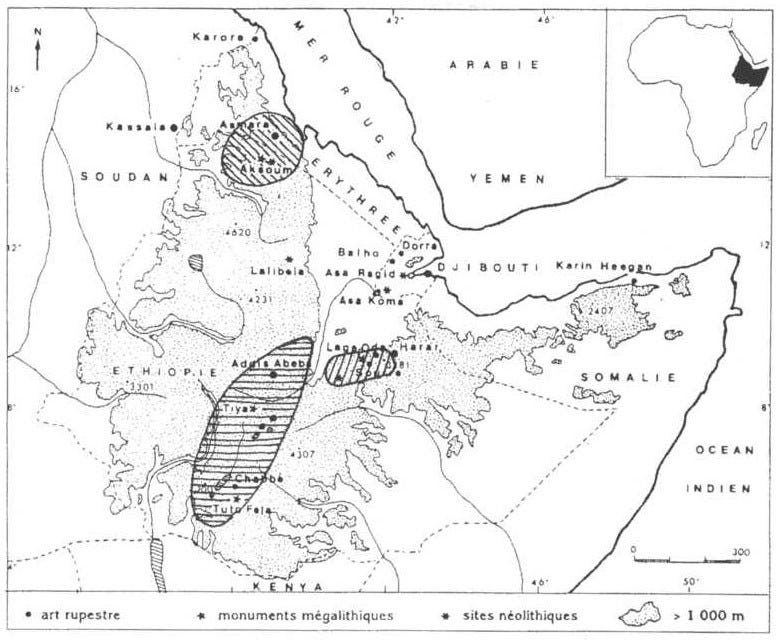

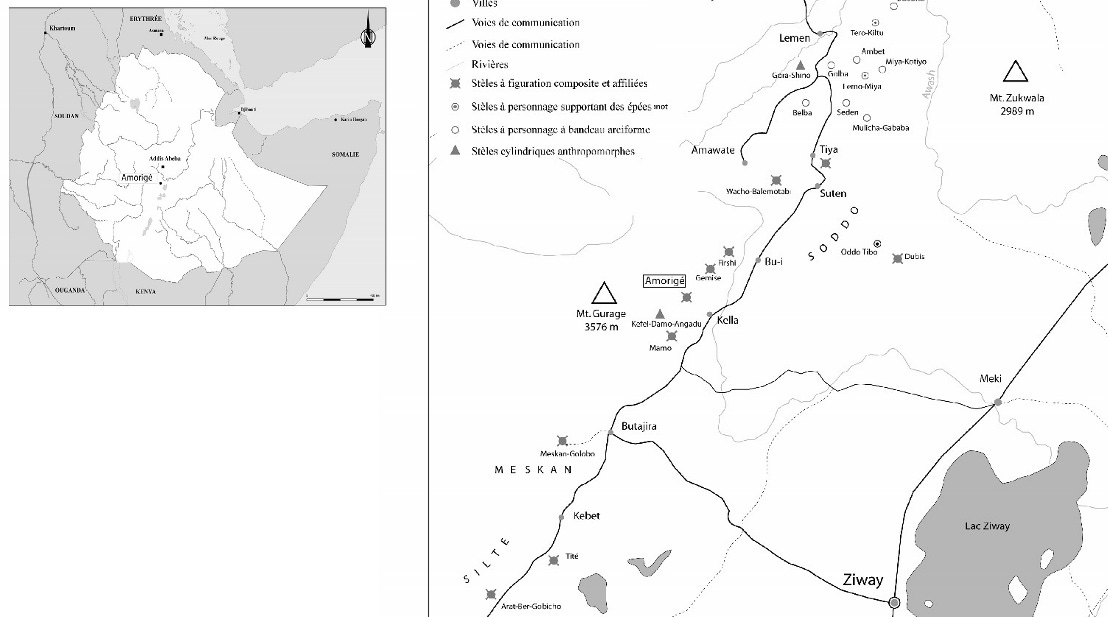

The megalithic sites of Ethiopia. Map by Jean-Paul Cros.

,

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Megaliths of the northern region

Megalithic stelae in Ethiopia display considerable variation in typology, scale, and chronology, and were erected within diverse social and economic contexts. Current archaeological evidence indicates that at least four largely independent traditions of stelae construction developed in the northern, eastern, central, and southern regions of the country.

Historical antecedents for megalithic construction of northern Ethiopia can be found in the archaeological sites of Mahal Teglinos (Kassala, Sudan) and Beta Giyorgis (Tigray, Ethiopia).

The former site, which belongs to the Neolithic ‘Gash group’ (c. 3000–1500/1400 BC), contains an elite cemetery with funerary stelae comprised of flat slabs, pointed monoliths, and small pillars, ranging from 0.5 to 1.1 m in height. At the proto-Aksumite site of Beta Giyorgis (400 BC- 50 CE), all funerary stelae were monoliths, around 4–5 m high, with a vertical notch at the top, suggesting one dominant lineage. They stood ontop of a tomb platform containing elaborately decorated pit-graves, around 5 m deep, and rich grave goods.1

(left) Mahal Teglinos (Kassala), Stele Field, Gash Group (right) Beta Giyorgis (Aksum), proto-Aksumite stele field. Images by Rodolfo Fattovich

In the late 1st century CE, the city of Aksum was established as the capital of the kingdom, and a new royal cemetery was opened, ontop of which stood several monumental stelae.

In the Early Aksumite phase, the shaft tombs in the northern half of the Stelae Park were covered by stone platforms and were associated with carved stelae, up to 10 m high. In the late 3rd century CE, a ‘royal’ cemetery with elaborate, rock-cut multi-chamber shaft tombs, massive stone platforms, and stelae was established in the main Stelae park. Another elite cemetery with monoliths was located to the west of the town, known as the Gudit stelae field. In the 4th century, monumental hypogeal tombs, such as the so-called ‘Mausoleum,’ and staircase tombs were associated with monumental hewn stelae in the ‘royal’ cemetery of the stelae park.2

The Obelisk at Axum. Drawing by Henry Salt, ca. 1809.

Axum: in the foreground, stele 1 lies broken on the ground, and on the right are the cover stone and pillars of the monument of Nefas Mawcha. In the background are two other giant stelae. WikimediaCommons.

carved details on Stela 3

Mausoleum of Aksum

Gudit Stelae Field

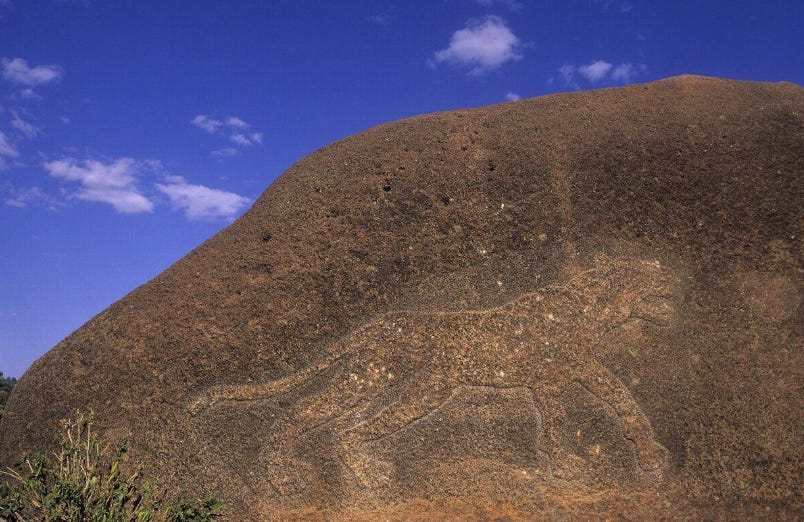

The largest of the stelae in the royal cemetery weighs over 520 tonnes, while two others weigh 160–170 tonnes each. They were elaborately carved in imitation of multi-storeyed Aksumite buildings, complete with window-frames and apertures, false doors, horizontal wooden beams, and the projecting ends (monkey-heads) depicted in low-relief carving. They were carved in a granite-like rock known as nepheline syenite that was obtained from quarries about 4 km to the west of the city, such as Gobedra, where there is a relief carving of a lioness.

Abandoned quarry near Aksum. WikimediaCommons.

The Lioness of Gobedra. Aksum, Ethiopia

Stela 3, which is thought to belong to King Aphilas or Wzb, is the only one of the three in its original position; standing at 20.6m high, and weighing 160 tonnes. Excavations on the site of the next largest stela, no. 2, thought to belong to King Ousanas, demonstrated that it had been intentionally undermined to make it collapse, many centuries ago, likely in the late 1st millennium CE. Stela 1, which is thought to belong to King Ezana, is the largest of the Aksumite stelae and arguably the largest single block of stone that people anywhere have ever attempted to set on end. 33m long and 520 tonnes in weight, it appears that it fell and broke during the attempt to erect it.3

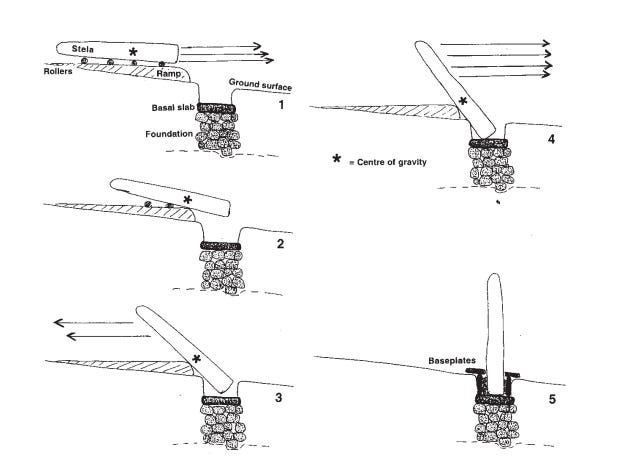

Archaeologists have reconstructed the process of erecting the stela, based on the fallen remains of Stela 4, at the eastern end of the main Stelae Park and the features of the other monuments. The stela was placed on a ramp that often took advantage of a natural slope. A socket was excavated adjacent to the foot of the ramp, its base and sides being lined with slabs of stone. The stela was then raised and tipped into the socket, stones being quickly packed around its base to secure it. Finally, horizontal baseplates were added to hold everything in place.4

Reconstruction of how the Aksum stelae were probably erected. Illustrations by D. Phillipson

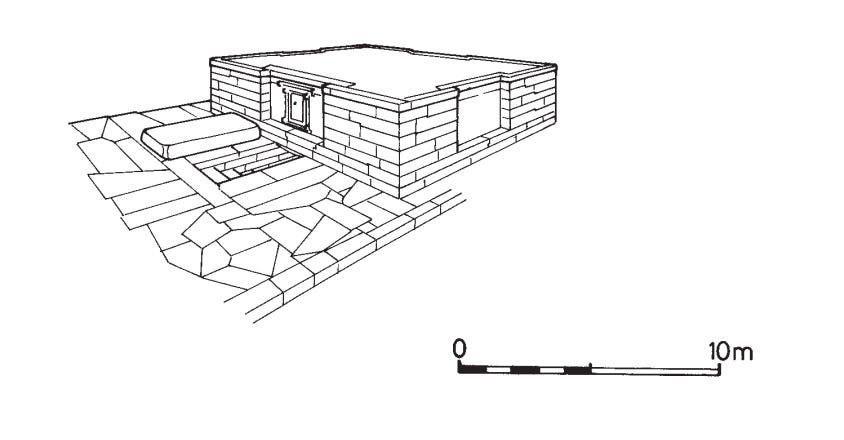

The unsuccessful attempt to erect Stela 1 coincided with major changes in royal burial practice and the formal adoption of Christianity that subsumed/replaced pre-existing funerary belief systems. The next monumental tomb, known as the ‘Tomb of the False Door’, was never marked by a stela; instead, its superstructure was a solid block of masonry 12 m square and 3 m high, incorporating a large stone slab carved to represent a false door virtually identical to those on Stelae 3-1.5

Later tombs belonging to King Kaleb and Gabra Masqal had churches constructed ontop, which appear to have replaced the funerary tradition associated with monumental stelae.

Reconstructed views of the superstructure of the Tomb of the False Door, Aksum, by N. Chittick

The southern megaliths

Chronologically, the megalithic constructions at Aksum overlap with those found much further south in the Gedeo and Sidama zones. These sites are north of the ancient megaliths of Turkana (Kenya), where massive sandstone pillars were erected in the 3rd millennium BC.

Gedeo and Sidamo contain the largest and highest concentration of carved megalithic stele in the country, with over 10,000 stele in at least 60 sites, dated from the 1st century CE to the 19th century.6

The southern megaliths of Ethiopia. Map by M. Monsillon

This region contains several stele sites, including Sakaro Sodo, Chelba Tuttiti, and Tuto-Fela. The oldest sites were at Soditi and Sakaro Sodo, which are dated to between the 1st-2nd century CE and the 8th century CE. Tuto Fela is dated to the 13th century CE, while Chelba-tutiti is dated to between the 17th-19th century.7

The site of Chelba-Tutiti comprises 800 to 1500 phallic stelae in an area of 1.5 ha. Most stelae measure around 2-3 m in height, but the largest are 6-8 m tall and weigh 8-10 tons. Most are hewn in ignimbrite and bear traces of paintings and engravings representing the vegetaliform sign. Limited excavations found a pit in the central part of the mound, associated with a stele painted with vertical and horizontal red bands.8

Geochemical analysis of the obsidian recovered from Chelba Tutiti suggests that the majority of the material was obtained from sources in northern Kenya, specifically from the Asille Group, located near Lake Turkana, 300km south. However, most of the stele were carved from local Basaltic rocks at quarries located relatively close to the locations where they were erected, often found between 1 and 1.5km from the stele sites.9

Tuto-Fela comprises two superimposed cemeteries containing a total of 320 stelae. The first was formed by funerary pits containing burial cells at the base that were filled with stones and fragments of phallic stelae. Above this is another cemetery made up of shallow pits and burials covered by stones.

The simple stelae with engraved cross braces, phallic stelae with cross-braces, and cross braces with faces, all belong to the upper cemetery. Unlike the phallic stelae which were worked with stone tools, some stelae in the upper cemetery show traces of metal tools.10

Sakaro Sodo stelae Image by A. Tixier

Tuto-fela stelae in Sidamo. Image by Yonas Beyene, UNESCO

Chelba-Tutiti stelae. Image by Yonas Beyene, UNESCO

There are many other stelae in Sidamo, all phallic and larger than those of Gedeo. They bear the vegetaliform sign, which is widespread in the southern regions, especially at Tiya.

Early excavations of a mound in Waheno bearing phallic stelae found a tomb containing human remains, a beautiful, polished axe, and many obsidian items. The foundational grave likely belonged to an important person, was buried under the mound, and was associated with the phallic stelae, while the rest of the stelae were erected in the course of time during commemorative or ritual activities.11

The eastern megaliths

Megalithic sites of Ethiopia. Map by R. Joussaume.

In the northern region of Ethiopia, the Aksumite kingdom slowly disintegrated during the 7th-8th centuries CE, as various states ruled by both Muslim and ‘Pagan’ monarchs emerged along its eastern frontier, the latter of whom were associated with the megalithic tombs found in the region.

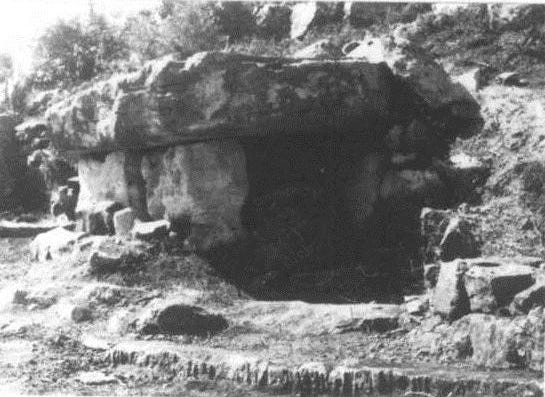

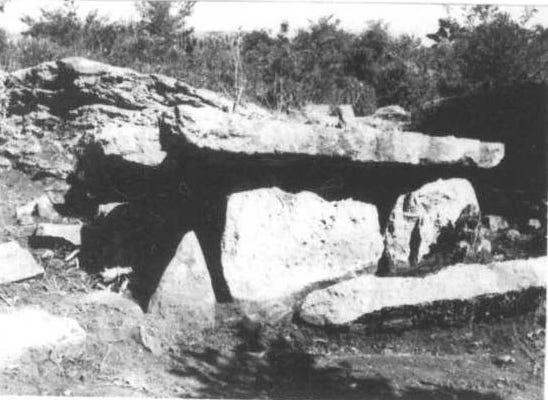

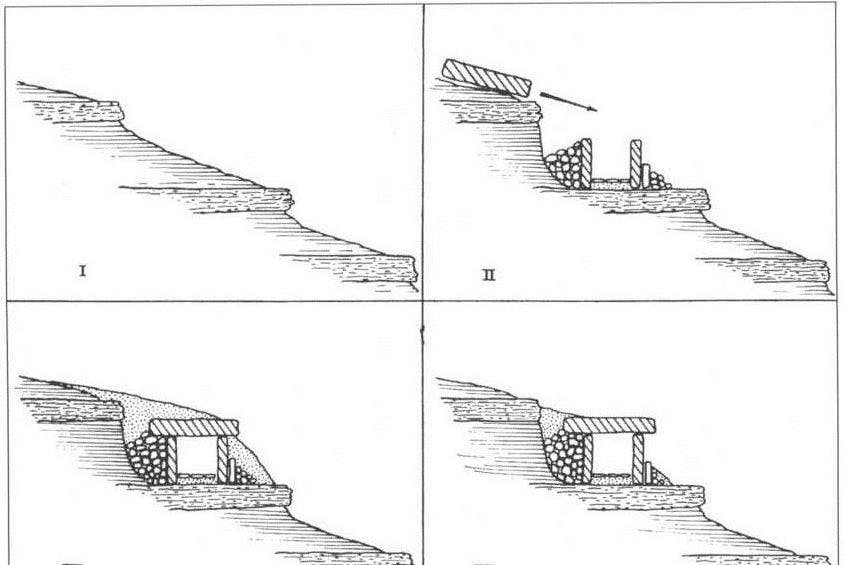

In this region, the earliest megalithic structures were dolmens (known locally as daga kofiya )constructed during the 2nd millennium BCE in the Chercher mountains near Harar. The monumental tombs were typically roofed by a limestone slab, the average of which measured 2.25 m long and 1.8 wide, and weighed 2-4 tonnes. The roof rests on two parallel rows of standing stones, delimiting a rectangular chamber with a paved interior measuring 1.45 x 0.65 m and 0.6-1m high, that is closed at each end by further slabs. Most were covered by a tumulus of stones and earth, and some were built around natural passages.

Their interior chambers are devoid of any remains, but charcoal from hearths found inside allowed them to be dated to between 2000-1500 BC and 1700-1250 BC. According to the archaeologist Roger Joussaume, the dolmens of Chercher could be contemporary with the Yemeni dolmens of the Tihama coastal plain. However, there is no further evidence to establish a possible link between these two funerary megalithic centers separated by the Red Sea. The domens are grouped in fairly small clusters: Chaffe, Surre Kabanawa, Hassan Abdi. They were built by small, settled, perhaps agricultural communities, probably organized into chiefdoms, of which only the elite were entitled to have their bodies interred in a daga kofiya .12

Three dolmens at Sourré, Harar. Image by R. Joussaume.

Daga Kofiya A7 of Hassam Abdi. Image by R. Joussaume

Daga Kofiya Sourré C 3 with a small triangular stele at the entrance. Image by R. Joussaume

Theoretical construction diagram of a daga kofiya (I to III) and the degradation of its covering tumulus. Illustrations by R. Joussaume.

After a seemingly long gap, megalithic construction resumed in the Middle Ages, with dolmen necropolises containing many stone tumuli (daga touli). The tumuli contain a circular collective burial chamber, some as large as 2.80 m in diameter with a height of 1m, compartmentalized into cells by vertical slabs. There was an access corridor lined with dry stone walls and upright slabs that led to this chamber.

Abundant grave goods accompanied the deceased, including round-bottomed ceramics, metal weapons, and ornamental elements. The structures date from between the 8th and 13th centuries CE, and belong to an Iron Age society known as the ‘Chercher culture,’ which was contemporary with the “Shay Culture.” 13

At Tatar Gour, a tumulus with a diameter of about 10m encloses a circular chamber with an access corridor. The whole structure was covered by another mound that would have masked the corridor. A high-ranking individual, accompanied by rich funerary deposits including an iron sword, occupied a privileged position in the centre of the chamber.

The tumulus of Tätär Gur, a passage grave built for an elite of the Shay culture during the mid-10th century. Image by B. Poissonnier and F. Fauvelle-Aymar

The tomb is dated to the early 10th century CE, and the material culture found at the site belongs to the ‘Shay’ culture, whose foundation is contemporaneous with the semi-legendary ‘pagan’ Queen Gudit, who defeated the last Aksumite king. The funerary tradition of the Shay culture declined in the 14th-15th century, as local populations adopted Christianity and altered their burial practices. 14

Sayǝṭān Gur, Menz Mama Woreda. This structure encompasses a tumulus, an extended drystone wall and a partly-destroyed external built platform. This tumulus uniquely displays a tunnel passage leading into a vault-shape chamber. Image and caption by Birru Alebachew Belay

Megaliths of the south-central region.

Megaliths in the Soddo region, Map by R. Joussaume

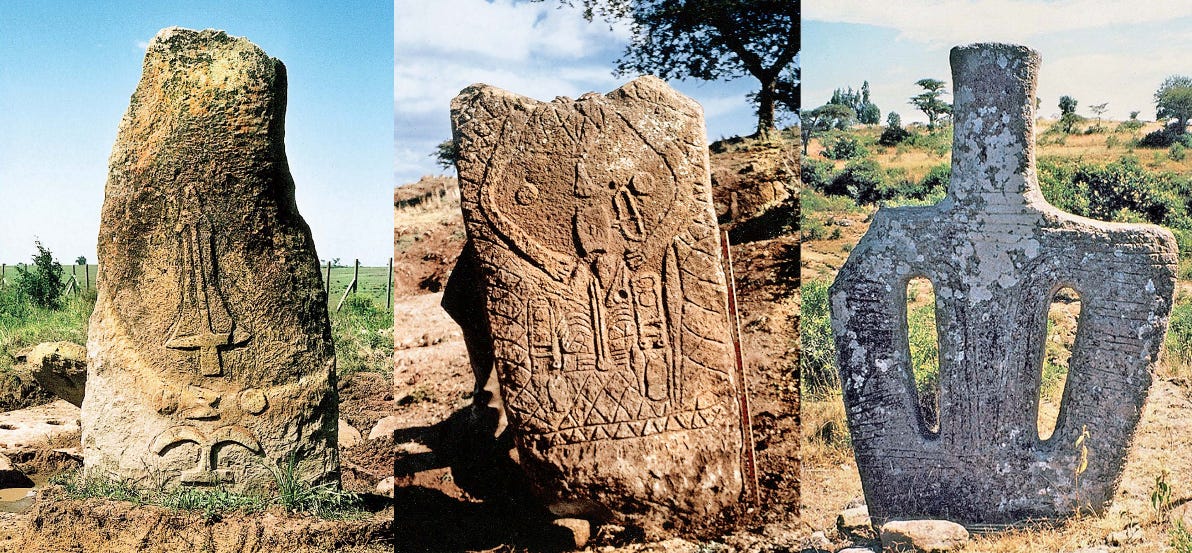

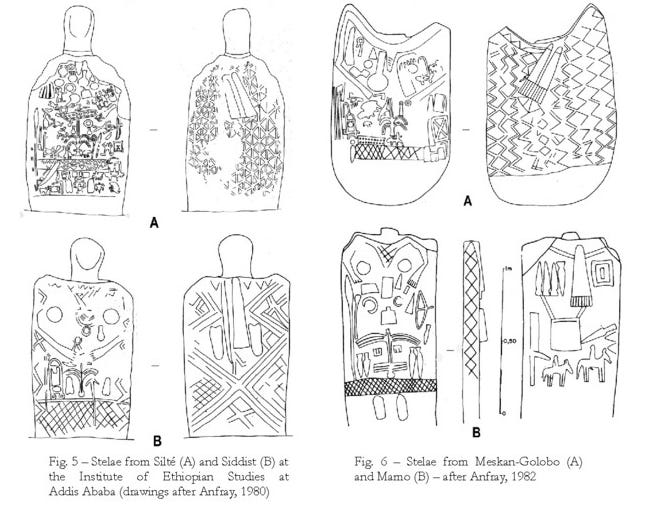

In the south-central part of Ethiopia, several megalithic sites were established in the region of Soddo, located south of Addis Ababa. Archaeologists divided the Soddo monoliths into two large geographical zones: a northern one characterized by “sword stelae” such as Tiya, and a southern zone which contains figurative stela.15

The archaeological site of Tiya is a cemetery containing 41 monoliths carved in ignimbrite using metal tools. The shaped stones, commonly categorised as “sword stelae” due to their decorations, vary in size from 1.3 to 5m in height.

Tiya

Standing stones at Tiya featuring carvings of with sword blades or lance-heads and ‘Y’-shapes. Image and caption by T. Insoll.

The Tiya stele tombs are pit graves, in which the deceased were buried, always a man first, sometimes in a wooden box. A stone slab or juniper branches closed the pit, which was marked on the surface by a space circumscribed by stones, where offerings were deposited in pottery vessels. Individual graves are predominant. The surrounding graves contain burials of women, attimes topped by a stele.16

Material culture found on the site included ceramics, glass beads, bronze and iron jewelry, scrapers, and blades. Radiocarbon dates obtained from the site by Roger Joussaume indicate that it was in use between 1200 and 1400 AD, and was abandoned shortly after the adoption of Christianity in the region around the 14th century.17

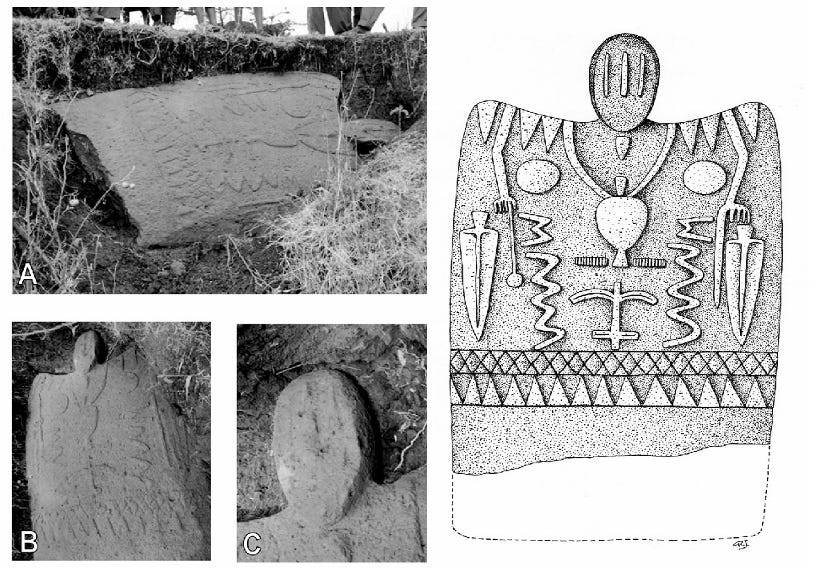

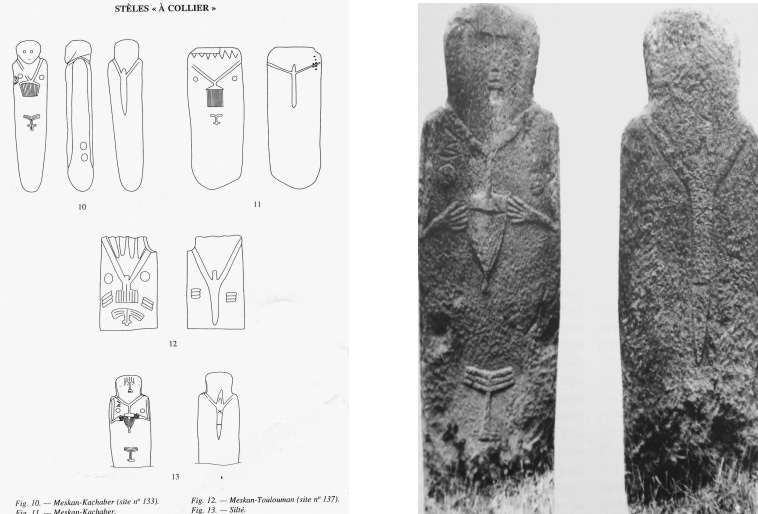

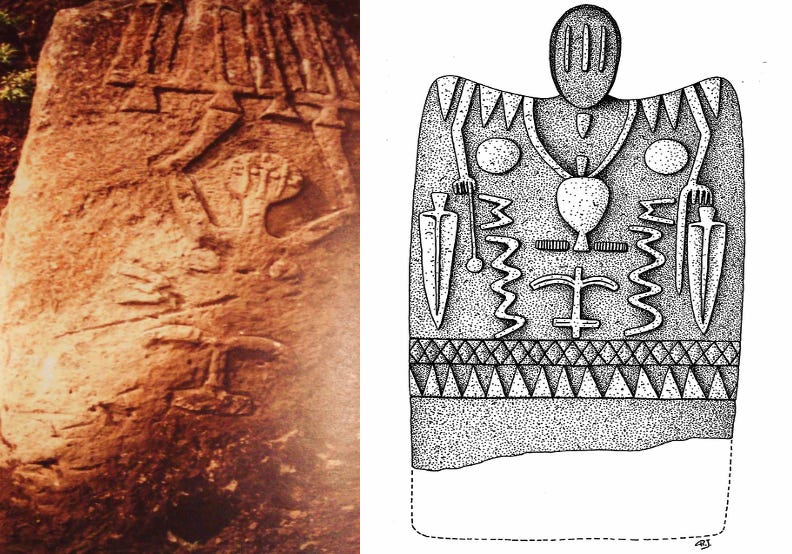

Similar stelae with intricately decorated surfaces are found throughout the region at sites such as Amorige, Wacho Balemotabi, Silte, Meskan, Tite, and Oddo-Tibo, among other sites, most of which are dated to between the 12th and 13th centuries. 18

(left) Amorigé stele: the stele in the bank of the temporary stream (A); general view of the stele (B); the stele’s compartmented face (C). (right) Drawing of the Amorigé stele: full height about 3 m. Images by R. Joussaume.

(left) ‘Sword stele’ from Tiya in Soddo. (center) ‘Stèle historiée’ from Tité, Silté region. (right) ‘Silhouette stele’ of Osolé in Soddo. Images by R. Joussaume

Symbolism and Function of the Ethiopian Megaliths.

The symbols found on the monoliths have been assigned various interpretations, but are still largely speculative given the diversity, age, and distribution of the stelae.

Phallic stelae are the oldest and dominant type in the southern regions, some of which are engraved with enigmatic signs and symbols, while the more recent and comparatively rare stelae with decorated surfaces are found in the south-central region.

The Phallic stelae, with a cylindrical body and hemispherical top sometimes highlighted by lines incised in the stone, are mostly found in the Sidamo and Gedeo regions. The “anthropomorphic” or “silhouettes” megaliths carved with human figures are mostly found in the Soddo region, with a few in Gedeo and Sidamo. They are triangular in shape, the point of which sinks into the ground, while the upper body has a cylindrical shape with two holes resembling eyes, and incisions/decorations below the “neck”.19

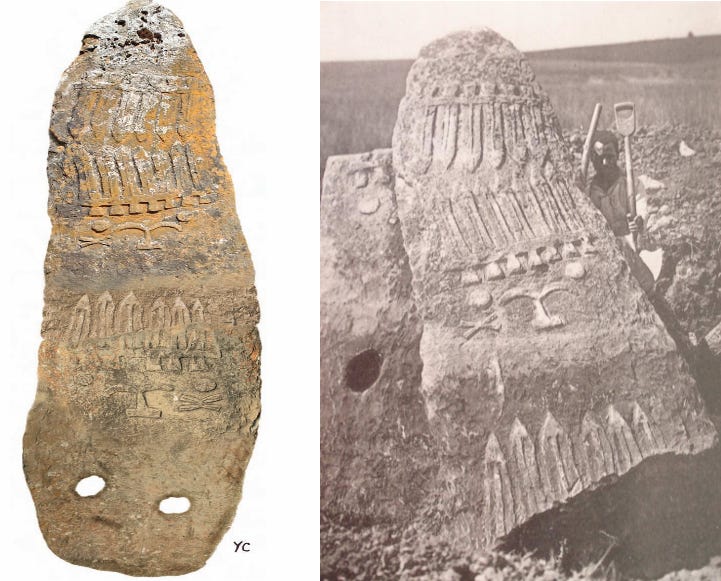

The “sword stelae” are composed of vertically elongated slabs, measuring 2-5 meters in length, with decorated faces. These decorations are organized into three levels: the base level contains one or more perforations, above these are a set of three symbols, and at the upper level, there are one or more “swords” in champlevé. These are mostly found in the northern Soddo at Tiya.20

Tiya stele, image by Ko Hon Chiu Vincent, UNESCO

(Left) The largest stele of Tiya: 5 m high with 19 swords. Note the two basal perforations. image by Y. Carpentier. (right) a “sword stele” at the site of Tiya in Soddo, Image by F. B. Azaïs and Chambard. ca. 1931-1935

Besides these are the “masked” or “partitioned-faced” stelae, which sometimes contain the same symbols as the sword stelae and the anthropomorphic stelae. They feature perforations for eyes and ears, as well as human figures with raised arms and pendulous forms likely representing breasts, suggesting female burials. There are also stelae described as “historiated” or “figurative”, which are large, flat stones with highly composite decorations of both human and animal figures, as well as clothing and everyday objects like flasks and sandals. Both of these types are found in the Soddo region.21

“Historiated” stelae at the Silté site in the Gurague. ca. 1931. Images reproduced by M. Monsillon

“Collared” stelae of the “Historiated” category, Photo and sketches by I. Pierre & E. Godet.

Engravings of daggers/swords suggest the use of metal weapons and hence could be interpreted as symbolizing the burial of a warrior or hunter. The “swords” have a wide, pointed, ribbed blade, pommel, and guard that resemble traditional Ethiopian daggers and Roman swords. Though it is dubious and debatable, the number of engraved daggers could possibly indicate the rank of the warrior or the number of enemies killed.22

There are engravings resembling the *letters “T”, “Y”, “W”, whose symbolism is not clear. ( *note that they are only compared to the Latin alphabetical letters for simple descriptive and linguistic convenience)

The “T” symbol recalls the headrest, which is common among many African societies, including in Ethiopia. According to Anfray, the forked signs could represent a branch of a tree, a projective weapon like a spear, or a branched stick held by the pilgrims of Dire Sheik Hussien. Roger Joussaume, on the other hand, suggests an anatomical interpretation of these signs, representing parts of the human body or places of scarification.23

(left) ‘sword Stele’ with representation of the signs of the “symbolic triad” on the “torso” of a “human figure”, at the Oddo-Tibo site. Image by M. Monsillon. (right) ‘Historiated Stele’ of Amorigé in Soddo with raised shoulders and elongated head with a partitioned face. Illustration by R. Joussaume.

Drawings of various stele from the south-central region megaliths of Soddo, Ethiopia.24

The perforations found at the bottom of the stones were unlikely to have been used during their movement, since they lack friction marks and are located near the edge, where the pulling would have broken them. According to Anfray, these perforations would therefore have no practical use for transport or stelae stabilization, but were likely decorative, with a metaphysical meaning. Joussaume suggests that the perforations symbolically linked the deceased with the outside world.25

According to most archeologists, the megaliths of Soddo and Sidama are stelae, funerary markers, which mark the location of graves. However, not all of them are associated with burials, and some, especially in Wolayta, do not have a funerary function and aren’t associated with cemeteries.26

Excavations at the Chelba-Tutitti site indicate that the phallic stelae are not strictly associated with burials, but rather arranged around low mounds that may have been funerary and that could have initiated the development of these large stelae sites. These stelae would have a commemorative function based on a primordial funerary rite, that of the “memory of the dead”. The “power of the living” would be expressed in the number of monoliths placed around this tomb, giving the whole its monumental character.27

Historical and ethnographic research suggests that some of the southern megalithic sites were associated with Sidama-speakers and related groups, since their function was unknown to present groups such as the Gurage and Oromo-speakers, whose oral traditions variously attribute them to the 16th-century Adal general Ahmad Gran and his followers. However, this tradition, which is part of the widespread legends about the Muslim general, contradicts the Islamic prohibition of the depiction of human figures and the fact that most of these sites predate this period.28

Importantly, the differences in style between the phallic stelae with a few engravings found in the Sidamo region and the highly decorated stelae of the Soddo region (e.g., at Tiya), both of which were carved around the same period, suggest social and cultural differences between the societies that erected the megaliths. The builders of the Ethiopian megaliths were thus heterogeneous, but had a shared tradition of erecting stone markers on the tombs of important figures, and on other occasions.29

Cultural and social changes, such as the adoption of new burial customs following the spread of Christianity and Islam in the late Middle Ages, may have altered historical traditions about the function of the megaliths among the present populations.

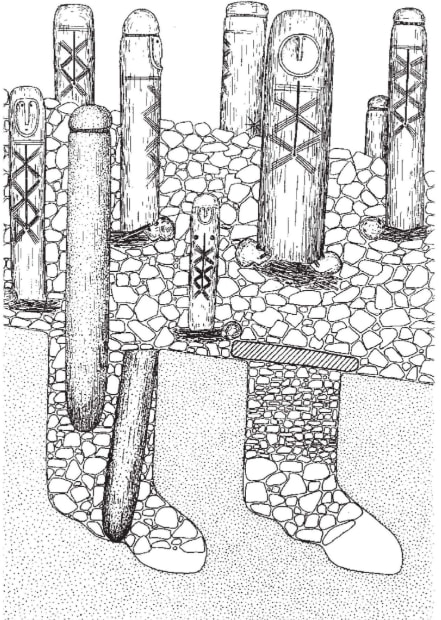

The living megaliths of the Konso.

In some regions of southern Ethiopia, communities where traditional belief systems persisted to varying degrees, such as the Konso, Gewada, Borana, Hadiya, and Arsi, still erect stones in funerary contexts or on other occasions. For the Konso in particular, their communities are structured by a complex generational and age-class system called gada, several variants of which are found among many southern populations.

The main square of the settlement (mora) contains dega hela stones, which mark the replacement of age class, as well as dega diruma stones, which mark the grave of an individual or an important debate. A dega diruma is erected on the tomb of a hero, together with wakas, the famous wooden statues representing the deceased wearing the helecha, a phallic symbol, on his forehead, his weapons.30

Grave of a Konso hero, with his wooden statues (wakas). Image by F. B. Azaïs. ca. 1931.

Anthropological research suggests that the waka represent the deceased who killed one or more enemies in a battle, or wild beasts like lions and leopards. The hero stands in the center, surrounded by his wives and the vanquished victims. They are carved from wood in a somber and rigid style, and often lined up in small groups on the main roads in the city.31

The Konso monoliths aren’t shaped stelae obtained from quarries but raw stones obtained from natural deposits. These heavy stones, weighing about 2.5 tonnes, are extracted from the ground and prepared by about 20 people. They are transported using wooden poles and fiber ropes, which form a kind of stretcher. The stone is then erected in the public square by about 120 people, with the help of poles placed at its top and ropes.32

(left) monoliths in the public square of a Konso village. (right) Arsi stele bearing the representation of a character. images by M. Monsillon.

Wooden statues ( waka ) and standing stone on the platform of a hero’s tomb. Image by R. Joussaume.

Tumulus with anthropomorphic stelae superimposed on a cemetery of shaft graves marked with a phallic stele. Tuto Fela site. Illustration by R. Joussaume.

Apart from a few present-day peoples in southern Ethiopia (Konso, Gewada, Hadya, Arsi) who still erect monoliths in connection with their dead, this custom seems to have been gradually abandoned with the adoption of Christianity and Islam near the end of the Middle Ages in the south-central regions.

However, the presence of a few “mixed” (Muslim & ‘pagan’) cemeteries near Heissa in the Harar mountains, with small stelae displaying both pre-Islamic and Islamic designs, including shapes of human figures and faces, suggests that this tradition may have persisted for some time in the eastern region33.

Heissa Cemetery, Image by F. Azaïs, ca. 1922.

Cemetery near Deder in Harar. Here the tomb is quadrangular, bordered by four stones on edge. One of the two end slabs has a disc carved out like a head. Image by R. Joussaume

Cemetery not far from Deder in Harar: general view. Image by R. Joussaume.

The ancient megaliths of Ethiopia were therefore the product of diverse social and ritual practices, including mortuary rituals, commemorative social events and ceremonies, practiced by many communities that make up the modern country. Through these activities, they produced one of the most prolific and distinctive megalithic traditions on the African continent.

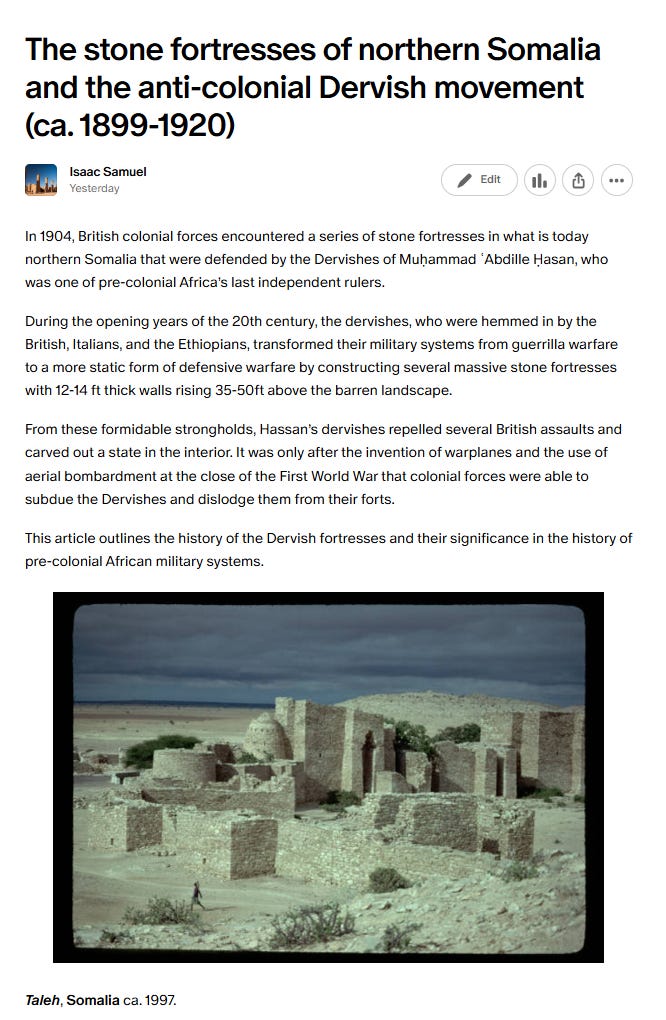

During the opening years of the 20th century, the anti-colonial Dervish movement of Muḥammad ʿAbdille Ḥasan in present-day northern Somalia constructed several massive stone fortresses with 12-14 ft thick walls rising 35-50ft above the barren landscape.

These fortresses, which held out against repeated British assaults, demonstrate the enduring strategic value of the ancient tradition of defensive architecture in Africa, despite the evolution of siege technology.

The history of the Dervish fortresses is the subject of my latest Patreon Article. Please subscribe to read more about it here and support this newsletter:

The Development of Ancient States in the Northern Horn of Africa by R. Fattovich, pg 154-155, 158. From Community to State: The Development of the Aksumite Polity (Northern Ethiopia and Eritrea), c. 400 BC–AD 800 by Rodolfo Fattovich

Foundations of an African civilisation: Aksum & the northern Horn, 1000 BC- AD 1300, pg 139

Foundations of an African civilisation: Aksum & the northern Horn, 1000 BC- AD 1300, pg 140-145

Foundations of an African civilisation: Aksum & the northern Horn, 1000 BC- AD 1300, pg 146-147

Foundations of an African civilisation: Aksum & the northern Horn, 1000 BC- AD 1300, pg 149-153)

Recent research on megalithic stele sites of the Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia, by Andrew I. Duf et al.

Recent research on megalithic stele sites of the Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia, by Andrew I. Duf et al., pg. 5

Megaliths of the World Volume 1, edited by Luc Laporte et al., pg. 993

Recent research on megalithic stele sites of the Gedeo Zone, Southern Ethiopia, by Andrew I. Duf et al., pg 5-7

Megaliths of the World Volume 1, edited by Luc Laporte et al., pg. 994

Megaliths of the World Volume 1, edited by Luc Laporte et al., pg. 993

Mégalithisme dans le Chercher en Éthiopie by Roger Joussaume, pg 37-96

Mégalithisme dans le Chercher en Éthiopie by Roger Joussaume, pg 97-167

La culture Shay d’Éthiopie (Xe-XIVe siècles) by François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar and Bertrand Poissonnier, pg 97-167, 200-225.

Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 27

Megaliths of the World Volume 1, edited by Luc Laporte et al., pg 992

Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 65-66, 69)

Amorigé and the anthropomorphic stelae with compartmented faces of Southern Ethiopia by Roger Joussaume

Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 36-37)

Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 38)

Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 39-41. Amorigé and the anthropomorphic stelae with compartmented faces of Southern Ethiopia by Roger Joussaume, pg 109-110.

On the Megalithic Sites of the Gurage Highlands: A Study of Enigmatic Nature of Engravings and Megalith Builders by Worku Derara pg 70, Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 82-88

Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 90- 98, On the Megalithic Sites of the Gurage Highlands: A Study of Enigmatic Nature of Engravings and Megalith Builders by Worku Derara pg 71

Amorigé and the anthropomorphic stelae with compartmented faces of Southern Ethiopia by Roger Joussaume, pg 110.

Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 99-101

Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 68-72

Des pierres phalloïdes par milliers en Éthiopie méridionale by Anne-Lise Goujon

On the Megalithic Sites of the Gurage Highlands: A Study of Enigmatic Nature of Engravings and Megalith Builders by Worku Derara pg 77-78. Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 15-16, 56-60.

Amorigé and the anthropomorphic stelae with compartmented faces of Southern Ethiopia by Roger Joussaume, pg 115.

De l’interprétation des tombes à stèles des Konso d’Éthiopie by Roger Joussaume

Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 45)

Mémoire M2: L’espace mégalithique du sud de l’Ethiopie (XIIIe - XVIe xiècles): Interprétations et géo-histoire By Margot Monsillon, pg 46-48)

Pierres dressées chez les Hadiya du sud de l’Éthiopie by Roger Joussaume

Nice Issac as I did visit Aksum some years ago and saw those huge megaliths and underneath chambers....they might be BC began as they did absorb the Kush Black Pharaoh technology and eventually their royal families...more archeology needs to be done