The complete history of Aksum: an ancient African metropolis (50-1900AD)

Journal of African cities chapter-3

For nearly 2000 years, the city of Aksum has occupied an important place in African history; first as the illustrious capital of its eponymously named global power; the Aksumite empire, and later as a major religious center and pilgrimage site whose cathedral reportedly houses one of the world's most revered sacred objects; the Ark of the covenant.

The city's massive architectural monuments, which include some of the world's largest monoliths and sophisticated funerary architecture, were the legacy of its wealth as the imperial capital of a vast empire. Despite the Aksumite empire's collapse in the 7th century, the city retained its allure as it was transformed into the most important religious center in medieval Ethiopia and continuously invested with sufficient political capital and ecclesiastical architecture well into the modern era, to become one of Africa's oldest continuously inhabited cities.

This article outlines the chronological history of Aksum, its architectural monuments and its political history from 50AD -1900AD.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Classical Aksum (50-700AD)

Aksum was established in the early 1st century AD after the rulers of the early pre-Aksumite polity shifted their capital from the site of Beta Giyorgis just north of Aksum, where they had been settled since the 4th century BC. Their nascent state was part of a millennia-old political and economic tradition that had been gradually developed across much of the northern Horn of Africa since the establishment of the D'MT kingdom in the 9th century BC and the preceding Neolithic Gash-group culture of the 3rd millennium BC.1

Aksum first appears in external accounts around 40AD when the anonymous author of the periplus of the Erythraean Sea records the existence of a metropolis of the people called aksumites that was ruled by king Zoscales, whose port city was Adulis. Over the 3rd century, the kings of Aksum progressively incorporated the surrounding regions; including much of the northern horn of Africa and parts of southern Africa, into a large territorial state centered at Aksum. The capital of Aksum was unmistakably the center of centralized royal power as inscriptions that were made beginning in 200AD position the title ‘king of Aksum’ before the list of peripheral territories over which the Kings at Aksum claimed suzerainty.2

The urban development of the capital was the dominant factor in the organization of the territory. Aksum is more accurately understood as a metropolis, a political, religious and commercial center with a conglomeration of monumental palatial structures, ecclesiastical structures and elite tombs were built over a region about the size of 1sq km housing an estimated population of 20,000, and was served by a network of paved roads that linked it to the provinces. The settlement itself was not enclosed within a defensive wall but its limits were marked by monumental stone inscriptions made by its emperors. The central area of Aksum didn't contain domestic structures, as they were located immediately outside of it and in the hinterland where monumental constructions similar but smaller than those at Aksum were constructed to serve as regional centres.3

Aksum's stone stelae and monumental stone thrones; most of which were found within the capital, were inscribed in three languages (Ge'ez, "pseudo-Sabaean" and Greek) using three scripts (Ge'ez, "ASAM", and Greek), hence the common term "trilingual inscriptions". They record the military campaigns and other administrative activities carried out at Aksum and the empire's provinces by the kings of Aksum. Atleast 12 of the royal inscriptions were made in Ge'ez language while 3 were made in Greek, all are attributed to 5 kings from the 4th to the 9th/10th century; Ella Amida, Ezana, Kaleb, Wazeba, Dana'el, the last of whom post-dated the empire's collapse.4

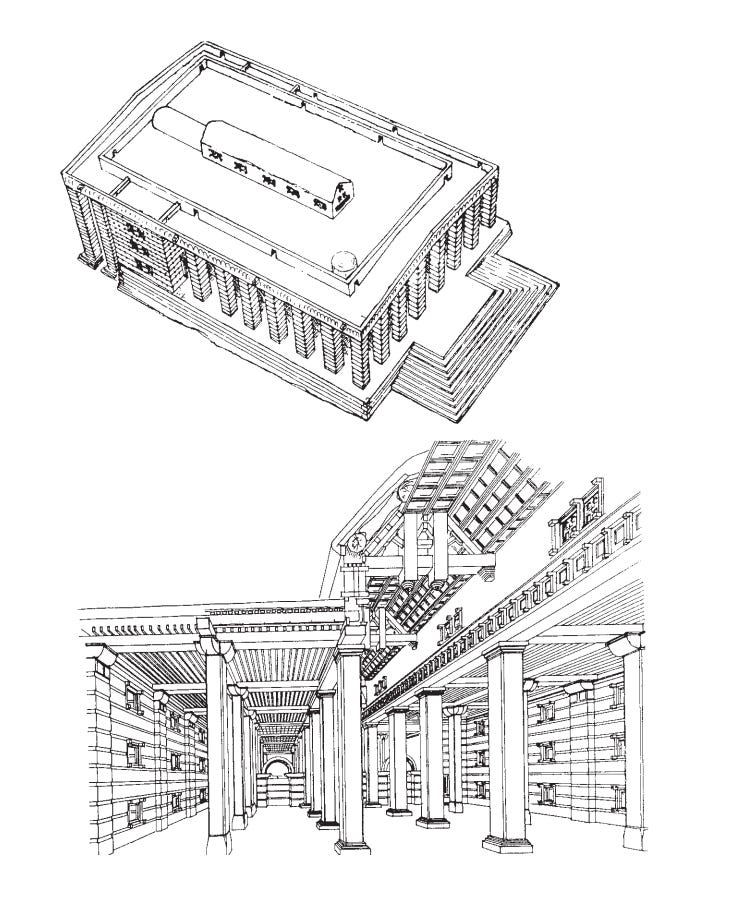

Aksumite architecture was characterized by the use of dressed rectangular stone blocks in construction, these were placed in neat courses with no mortar (except for the occasional use of lime mortar), with walls reinforced by a framework of timber beams. The stone walls incorporated horizontal beams held together by transverse beams whose rounded ends that extended outside the façade were called ‘monkey-heads’. Flat roofs supported by stone pillars with stepped bases and arches made of fired-bricks were covered with stone-slabs and floors were made of stone paving with dressed rectangular slabs.5

Map of Aksum’s main archeological sites6

Elite structures at Aksum.

Aksumite mansions/villas (at times called Palaces) were the largest and most elaborate residential structures in the metropolis. Each comprised a grand central building or pavilion often set on a high foundation or plinth, with the main house made up of at-most three storeys (plus the occasional basement) in a courtyard surrounded by suites of rooms constituting an extensive complex, that was accessed via a series of monumental stair cases. The largest of these villas was Ta‘akha Maryam that covered the size of 1 hectare and was among the largest palatial residences of the ancient world, others include Dungur, Enda Mikael, and Enda Semon.7

the Dungur ‘palace’

Plan of Ta‘akha Maryam élite structure at Aksum

May Šum reservoir / Queen of Sheba’s pool possibly of Aksumite date.8

Aksum’s religious architecture

Christianity was adopted in Aksum between 333 and 340 by King Ezana and its presence was soon attested on Ezana's inscriptions and coinage, although the religion's acceptance by the wider population was gradual processes that took centuries, and was symbolized by the construction of large churches (basilicas).9

Aksum's oldest basilicas in the capital were essentially an Aksumite variation on the basic basilica typology of the Mediterranean region, as it had a five-aisled hall rather than the usual three-sided arrangement, and it also retained the characteristic Aksumite features, with courses of stone alternating with wooden beams connected by ‘monkey head’ crosspieces. The most typical classic plan of the Aksumite basilica was the church of Māryām Şĕyon built during the 6th century by king Kaleb at Aksum but destroyed during the Abyssinia-Adal wars of the 16th century and later reconstructed in the 17th century. Others include the Basilicas placed over the rockcut tombs of Kālēb and Gabra Masqal at Aksum.10 Another Basilican church named Arba‘etu Ensesa was built in the 6th century in Aksum. It measures 26 x 13 m. It had a subterranean chamber accessed externally via a flight of stone stairs, and was fitted with storage niches framed by ornamental stone-carving.11

panorama of the smaller reconstructed church of Māryām Şĕyon, the old podium and staircase of the original basilica is still visible

reconstructions of the original Maryam Tsion Cathedral at Aksum by Buxton & Matthews 1974

Arba‘etu Ensesa church and basement, reconstruction

tombs of Kālēb and Gabra Masqal and a plan of their Basilicas

Domestic architecture of non-Elite residents.

Lower status Aksumite houses were rectilinear constructions surrounded by open courtyards that were intersected by narrow lanes.12 The so-called "domestic area" in the northern section of Aksum features a residential complex built in the 5th century and was abandoned soon after its construction. Less monumental constructions of roughhewn stone that were constantly modified, were erected near the old structure after its abandonment during the 6th century. Another non-elite settlement was at Maleke Aksum, where rough-hewn stone buildings were constructed in the 6th century and the material culture recovered from inside the residential areas includes debris from crafts production including metalwork, glass-making and lathe-turning of ivory. Both elite and "domestic" houses also contained a number of Aksumite coins.13

Domestic architecture at Aksum

rock-cut wine-press at Adi Tsehafi near Aksum

Aksumite coinage, funerary architecture and inscriptions.

The minting of gold, silver and copper coinage at Aksum begun in the 3rd century and continued until the 7th century. Different coins with Ge'ez and Greek inscriptions are attested at Aksum and attributed to the kings; Endybis (270-290), Aliphas, Wazeba, Ella Amida, Ezana (330-360), Wazebas, Eon, MHDYS, Ebana, Nezana, Nezool, Ousas, Ousanas and kaleb (510-540), Ioel, Hataz, Gersem and Armah (7th century). The coins were struck in the capital and depict the monarchs' portraits framed by cereal-stalks and surmounted by a religious symbol. The gold coins were used in internal trade while copper and silver coins were used in regional trade.14

various Aksumite coins from the 3rd-7th century, British museum

Aksum’s funerary architecture and stone Thrones.

Aksum's central stelea area was gradually built up between the 1st and 3rd century on a series of terraces and platforms, under which were subterranean tombs were carved in substrate rock. The most monumental stelae weighed 170-520 tonnes, and stood ata height of 24-33m, and their associated tombs were the last to be constructed in the early 4th century for Aksum's emperors who were by then presiding over one of the world's largest empires. The stelae were elaborately carved to represent multistoried buildings with typical Aksumite architectural features including monkey-heads and false doors.15

The largest of the subterranean royal tombs was the western "Mausoleum" complex, an massive construction built 6 meters deep that extending over 250 sqm, and was roofed with large, rough-hewn granite slabs supported by monolithic columns and brick arches. The tomb had ten side-chambers leading off a central passage, and is understood to have housed the remains of the 4th century kings of Aksum and contained luxury grave goods that were robbed in the past.16

Another was the tomb of brick arches is approached via a descending staircase, at the foot of which is a horse-shoe shaped brick arch that opens into the main tomb about 10 meters below the ground surface. The tomb chamber comprises of four rock-cut chambers that were carved from surrounding rock and divided by stone cross-walls and with roofs supported by brick arches built with lime motar. The tomb contained a lot of luxury goods that were robbed in the past, with only elaborate metalwork and ivory carvings recovered in the early 20th century. Other elite tombs at Aksum include Nefas Mawcha and the Tomb of Bazen.17

The Gudit stelea Field was the burial ground for lower status Aksumite individuals. The subterranean tombs were built in the same form as the elite tombs with staircases leading down into an underground chamber, but rather than rock-cut chambers, they consisted of a simple pit containing few grave-goods and surmounted by small rough-hewn stela.18

Main stele field at Aksum, carved details on Stela 3

entrance to the Tomb of the False Door and Tomb of brick-arches

Mausoleum of Aksum

Stone throne bases at the outer enclosure of the Cathedral of St. Maryam Tsion

Gudit Stelae Field and other shaft tombs including the ‘Tomb of Bazen’

Inscriptions of King Ezana at Aksum.19

Aksum during the ‘Post-Aksumite’ and Zagwe era (700-1270)

Aksum decline as the power of the Aksumite empire waned in the late 6th/early 7th century not long after the reign of king Armah (possibly the celebrated Negash of Islamic tradition that sheltered prophet Muhammad's persecuted followers). The population of the capital diminished sharply, many of its grand monuments were largely abandoned as the center of power shifted to the region of eastern Tigray at a new capital referred to in medieval Arabic texts as Jarma or kubar. The former is first mentioned by al-Khuwarizmi (833) and Al-Farghani (861) while the latter is first reported by Al Yaqubi in 872.20

The post-Aksumite era is relatively poorly documented internally, with the few contemporary records about Aksum coming from external accounts. An enigmatic general-turned-king hatsani Dana’el is attested at Aksum by his inscriptions made on broken throne fragments and is variously dated to between the 7th and 9th century. The inscriptions document his campaigns across the region including a civil war within Aksum itself, another in Kassala (in eastern Sudan) to its east and one against the king of Aksum whom Dana'el deposed, imprisoned and released to serve as his subordinate.21

The period after Dana’el's reign is described in external documents by Arab authors which offer some insight into the political situation at Aksum, with three different documents from the late 10th and the mid-11 century alluding to an enigmatic queen Gudit governing the region around Aksum. In the years after 979AD, an unnamed King of Aksum reported to the King King George II of Makuria (Nubia) that queen of Banū l-Hamuwīya (presumably Gudit) had killed Aksumite royals and sacked Aksum and other cities. While Gudit's devastation of Aksum definitively marks the end of its role as a royal capital, the activities of the church in Aksum headed by the metropolitan Mikaʾel in the 12th century, affirmed the primacy of Aksum as an ecclesiastical center with reportedly 1009 churches consecrated in the eyar 1150AD (no doubt an exaggeration).22

Over the 12th and 13th century, Aksum was part of the Zagwe Kingdom, more famously known for its other ecclesiastical center Lalibela. Despite the deliberate mischaracterization of the Zagwe as usurpers by their successors (the Solomonic dynasty) who claimed the former broke the Aksumite line of succession, It was under the Zagwe that Aksum was gradually restored, especially because of the activities of the abovementioned metropolitan Mikaʾel, and this renewed interest in the old city can also be gleaned from the Zagwe kings' appointment of officeholders at Aksum eg king Lalibela's administrator of the church of Aksum (qäysä gäbäzä Ṣǝyon).23

inscriptions of hatsani Dana’el at Throne No. 23, Aksum

Medieval Aksum under the Solomonids (1270-1630)

In 1270, the Zagwe dynasty was overthrown by the Solomonic dynasty and Aksum was gradually brought under the latter's control with both its founder Yəkunno Amlak and his successor Yagba Ṣəyon recorded to have been campaigning in the region. In the early 14th century, Aksum was under the rule of Ya’ibika-Egzi of Intarta, presumably a break-away state that had rebelled against the Solomonic emperor Amda Seyon (1314–44). Yeshaq, the author of the kebra nagast who was also the nebura’ed (dean) of Aksum (an office that appears in the Solomonic era) originally composed the text between the years 1314–1322, in service of his patron Ya’ibika-Egzi before Amda Seyon captured the latter at Aksum in 1316/17 , and appropriated the Kebra Nagast as the Solomonic national epic, and Aksum later became the coronation site of Solomonic monarchs.24

Aksum continued as a venerated ecclesiastical center and important site of imperial power during the Solomonic era especially beginning In 1400 with Dawit I's coronation and in 1436 with Zara Yaqob’s coronation and 3-year stay in the city. Zara’s coronation was an elaborate ceremony that included seated on the coronation throne (one of the Aksumite stone thrones) for the actual ceremony, and was repeated by most of the succeeding Solomonic monarchs25. Aksum's scribes composed the 15th/16th century ‘Book of Axum’ (Liber Axumae), a detailed cumulative compilation that was expanded by each generation; it describes the city's ancient monuments, contemporary structures, as well as its political history. 26

In the early 16th century, increasing diplomatic contacts between the Ethiopian monarchs and visits by Portuguese envoys in Ethiopia also provide detailed accounts of the city of Aksum. An account written in 1520 by Francisco Alvares provides a full description of Aksum including its churches (especially the Māryām Şĕyon just before its destruction in 1535), its houses, ruined monuments, stone thrones, water wells, and ancient tombs. Subsequent descriptions by Pedro Paez (1603) and Manoel de Almeida (1624-1633) and Alfonso Mendes (1625) would record the aftermath of Aksum's through destruction during the Abyssinia-Adal wars; with only 100 households left in the then ruined town by the time of Almeida's visit, but the latter also noted that royal coronations still took place at the diminished site and provided further descriptions of the ancient stela.27

After the sack of 1535, Aksum wasn't rebuilt by its residents until 1579. But by 1611, the now small town was again sacked during wars between Susenyos and the Oromo, its inhabitants fled and it shrunk in size to a population of less than 1,000. Aksum's population gradually increased over the course of the 17th and 18th century to about 5,000 despite records of locust swarms in 1747 and 1749 that devastated its hinterland.28

15th century copy of the Kebrä nägäst at BNF, paris

Aksum, from the Gondarine dynasty to the early modern era (1630-1900)

After the 17th century emperor Fasilädäs had established a permanent capital at Gondar in 1636, he initiated a grand construction project across the empire that included the restoration of the Māryām Şĕyon church in 1655 that was re-built in Gondarine style and extended by his successor Iyasu II in 1750. The present ‘Old Cathedral’ of Fasilädäs Aksum, stands on a massive podium of the ruined basilica that covered an area of 66 m by at 41 m, with a broad flight of steps at the west end29. In 1770, the explorer James Bruce arrived at Aksum as part of his journey through Ethiopia, he described the restored Gondarine church and the "very extensive ruins", and estimated that the town's was home to around 4,000 inhabitants.30

In the 19th century Aksum was visited by various explorers including Henry Salt (1805, 1809) and Theodore Bent (1893), all of whom left detailed descriptions of its ancient monuments and inscriptions.31 The elaborate coronation ceremonies at Aksum which had ceased during the turbulent “era of princes” of the late 18th century, were resumed under emperor Yohannes IV, who was crowned at Maryam Seyon church in 1872.32Yohannes undertook some significant construction work at Aksum as he had done in other cities, and commissioned the construction of a 'treasury'33, but his relatively long stay in the city may have exhausted its agricultural resources and influenced his return to his capital Mekelle.34

Because of the gradual advance of the Italian colonial forces into northern horn of Africa with the establishment of the colony of Eritrea in 1890, Yohannes' successor Menelik II wasn't crowned at Aksum but at Entoto in 1899. Aksum fell under Italian control in 1894 after its un-armed clergy chose to submit rather than face what would have been another devastating destruction of the city, but this brief occupation of Aksum turned to be a prelude to the inevitable war between Menelik and the Italians as both armies arrayed themselves not far from Aksum in February 1896 for the battle of Adwa.35

The ancient city of Aksum was spared, and its clergy, who had reportedly carried the Tabots (tablets) of Mary and St. George to the battle of Adwa, are traditionally credited with securing Ethiopian's victory over Italy through divine intervention.36

Fasilädäs’s 17th century reconstruction of the Māryām Şĕyon church

The treasury of Yohannes IV at Maryam Seyon church, Aksum

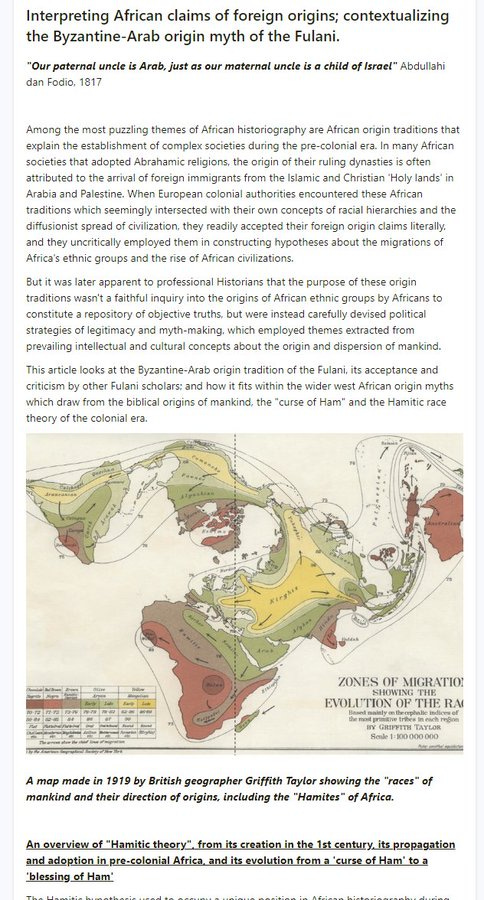

Legends of FOREIGN IMIGRANT rulers are a popular theme in the ORIGIN TRADITIONS across various African societies.

In this PATREON post, I explain why a number of African groups ascribe the establishment of their civilizations to foreign founders and how these traditions were misused in colonial literature to misattribute African accomplishments to “foreign civilizers”

The Development of Ancient States in the Northern Horn of Africa by R. Fattovich pg 154-157

Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity by S. C Munro-Hay. pg 41-42, Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 71)

Africa's urban past by David M. Anderson pg 61, Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 49)

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 51-55, 58-62)

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 121-123)

credit: Hiluf Berhe Woldeyohannes

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 124-123)

State formation and water resources management in the Horn of Africa by Federica Sulas pg 8

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 98-99)

The Basilicas of Ethiopia by Mario Di Salvo pg 5-11)

Archaeological Rescue Excavations at Aksum, 2005–2007 by T. Hagos

Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity by S. C Munro-Hay. pg 118-199

Africa's urban past by David M. Anderson pg 57)

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 82, 181-193)

Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 139-143)

.Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 143)

Africa's urban past by David M. Anderson pg 53)

Africa's urban past by David M. Anderson pg 55)

image credit for this set; David Phillipson

Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity by S. C Munro-Hay pg 95-96, Foundations of an African Civilisation by D. W Phillipson pg 209-212,

Archaeological Rescue Excavations at Aksum, 2005–2007 by T. Hagos pg 20-25)

Letter of an Ethiopian King to King George II of Nubia Benjamin Hendrickx pg 1-18, A companion to medieval eritrea Samantha Kelly pg 36-40)

A companion to medieval eritrea Samantha Kelly pg 48)

A companion to medieval eritrea Samantha Kelly pg 64-65, 238 The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 84-87)

Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity by S. C Munro-Hay pg 162

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 90-91, 100, Aksoum (Ethiopia) by Hiluf Berhe Woldeyohannes pg 44-50 )

Aksoum (Ethiopia) by Hiluf Berhe Woldeyohannes pg 61-75 )

Cities of the Middle East and North Africa by Michael Dumper pg 20

Aksoum (Ethiopia) by Hiluf Berhe Woldeyohannes pg 76-77, The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 155)

The Urban Experience in Eastern Africa, C. 1750-2000 by Andrew Burton pg 6

Aksoum (Ethiopia) by Hiluf Berhe Woldeyohannes pg 78-90

The Ark of the Covenant by Stuart Munro-Hay pg 94

Semitic Studies in Honour of Edward Ullendorff by Geoffrey Khan pg 280

Cities of the Middle East and North Africa by Michael Dumper pg 20

The Battle of Adwa By Raymond Jonas pg 93-94, 106, 125

The Battle of Adwa By Raymond Jonas pg 183

Amazing and I will go all through the pages.

Gudit is a funny pejorative title. In Amharic, it means the harmful one (fem.), and it rhymes with Yodit (Judith) in a sing-song way like the Americanisms: willy-nilly, heebie-jeebies, and dilly-dally.