Monumentality, Power and functionalism in Pre-colonial African architecture; a select look at 17 African monuments from 5 regional architectural styles

African architecture is the most visible legacy of the african past, a monument from the continent that is home to some of the world's oldest civilizations and arguably the most diverse societies

The different styles of African architecture are a product of their various functions, from the ostentatious symbols of power like the gondarine castles, the nubian catsle-houses and the madzimbabwe (houses of stone), to the religious monuments like the temples of kush, the great mosque of djenne and the rock hewn churches of lalibela, to the seats of royal power like the palatial residences of the hausa kings and the administrative halls of the sudanic rulers, to the functional and trivial features such as the sunken courts of swahili houses, the vaulted roofs of the swahili, nubian, ethiopian and hausa buildings, the underfloor heating of the aksumite and nubian houses, the imposing facades of sudano-sahelian houses, the baths and pools of meroitic, gondarine and swahili palaces, the indoor toilets, bathrooms and drainage systems of the asante, sudano-sahelian, swahili, houses, the decorative motifs of the hausa houses, the engravings on dahomey palaces, the murals and paintings on nubian and ethiopian walls, the swahili zidakas and interior shelves among many others

African architectural features are too many to be exhausted in just one article, but in writing this, ill try to condense as best as I can, the most distinctive regional styles across the continent (outside northafrica)

Support African History Extra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more on African history and keep this blog free for all:

Middle Nile and Sudanese architecture

This region between the first cataract of the Nile near Sudan's border with Egypt and the 6th cataract north of the Sudanese capital Khartoum has been home to Africa's oldest civilizations beginning with the "A-Group" Neolithic in the 4th millennium BC contemporary with pre-dynastic Egypt, its therefore unsurprising that this region has the most diverse architectural styles on the continent

The western defuffa temple; a Kerma kingdom monument

The principle temple of the city of kerma was built in 2400BC and destroyed in 1450BC. Standing at a height of 18m with its massive walls covering a surface of 52 by 26 meters; it was one of the largest buildings in the ancient world

The original complex was accessed through narrow passage ways leading into its four chapels, a long stairway leading into the its sancta sanctorum continuing up to its roof-terrace on its eastern side was a massive pylon

The temple has over the millennia been eroded into a large mass of mudbrick although some of the original features can be made out1

The Meroitic temple complex of Musawwarat es sufra, from the kingdom of kush

Covering over 64,000 sqm and built in the 3rd century BC, this enigmatic temple complex is perhaps the most impressive ruin from the kingdom of kush

The principal deity at musawarrat was apedemack, the lion-god of kush and the architecture is largely kushite featuring labyrinthine complex of rooms, shrines and room clusters built on artificial terraces with rows of columns and open courts surrounded by a maze of subsidiary buildings and perimeter walls, it's also punctuated with Meroitic iconography in its relief figures, with column bases of lions, elephants and snakes2

It also combines distinct architectural styles only featured in Kush’s architecture (especially at the city of Naqa in Sudan) and includes a few rooms whose construction styles parallel those from 25th dynasty Kush and Ptolemaic Egypt3

The throne hall at old dongola

Built in the 9th century by King Georgios I of the nubian kingdom of makuria, this imposing 9.6m tall two-storey administrative building is one of the best preserved secular constructions from the kingdom of makuria

Built with sandstone, redbrick and mudbrick, It consists of a ground floor 6.5m high and the first floor 3.1m high that was accessed by a grand staircase that continued to the roof terrace

The first floor is roughly square surrounded with a corridor running around it

The interior rooms were narrow and barrel vaulted, the windows were originally arched and the walls were lavishly painted

It was later converted to a mosque after 1317 and gradually deteriorated after makuria's fall until the late 19th century4

Ali Dinar's audience hall, in the capital of the kingdom of Darfur

Built around 1910 it was the audience hall and administrative building of Ali dinar who was the last independent king of the Darfur kingdom, a descendant of the keira dynasty from the fur ethnic group

The building was described by one British official after its capture as; "the sultan's palace is a perfect Sudanese Alhambra, the khalifa's house at omdurman is a hovel compared to it. There are small shady gardens and little fish ponds, arcades, colonnades,

the walls are beautifully plastered in red, trellis work in ebony is found in place of the interior walls and the very flooring of the women’s quarters under the silver sand is impregnated with spices. The sultan also had other fine residences in fasher"5

While it hasn't been studied, the architecture doesn't deviate much from the typical Darfur and Tunjur palaces of brick and stone from the 14th-19th centuries6

The architecture of the horn of Africa

The northern horn of Africa was home to some of Africa's oldest states beginning with the enigmatic kingdom of D'mt in the mid second millennium BC and the kingdom of Aksum from the late 1st millennium BC to the late 1st millennium AD

The latter was centered at Aksum in northern Ethiopia but expanded as far as the middle Nile valley and across the red sea to south western Arabia

The elite residence at Dungur; an Aksumite masterpiece

The villa (elite residence) at Dungur, was occupied in the 5th century, built in typical Aksumite style using dry-stone and timber, the multi-storey construction was one of several elite residences in the kingdom (that are often mischaracterized as palaces) the extensive complex covers over a third of an acre, with an imposing central pavilion, a grand staircase and projecting towers, the interior features ovens and underfloor heating, drainage facilities, carved pillar bases and several interconnected houses attached to the central building7

These "villas" housed provincial rulers and were ceremonial centers of the kingdom8

The rock-cut church of Medhane Alem at lalibela

it was one of about a dozen churches in the city of roha, Ethiopia the capital of the Zagwe kingdom -a successor of the Aksumite state- while it hasn't been accurately dated, it was complete by the time of king lalibela's reign in the 12th century (lalibela is the zagwe king whom all of the rock-hewn churches are attributed)

Measuring 33.5m by 23.5m and standing at 11.5m9, this church includes some of the typical Aksumite pillars, vaults, doorways, ornamentation and open-air courtyards while these rock-cut churches were partly Aksumite inspired as there are several aksumite rock-hewn churches from the 5th century, the lalibela churches were built upon the non-Christian troglodytic defensive structures of the post-Aksumite era10

The Fasiladas castle and gondarine architecture

After 1636, "solomonic" Ethiopia abandoned its practice of mobile capitals and founded a new city at Gondar, one of the city’s defining features are its famous castles, a product of increasing influence of the indo-muslim architecture of the mughals on Ethiopia's Aksumite and Zagwe architecture

This new style of construction is best represented at Fasildas' palatial residence, which was inspired by his predecessor Susneyos' castle at Danqaz and Sarsa Dengel's Guzara castle

Its made up of three storeys and is the tallest among the more than 20 palaces, churches, monasteries and public and private buildings in the 70,000 sqm complex known as Fasil Ghebbi

The castle is about 90ft by 84ft with circular domed towers at its corners and its walls over 6 feet thick, with several balconies, the interior contains several rooms, the roof is supported by a number of vaults and the castle includes an elaborate drainage system

the first floor contains the audience court and dining rooms, the second floor was for entertainment while the third was the emperor’s bedroom11

The architecture of west Africa

Home to some of Africa's oldest cities, west Africa is also the region with one of the most distinctive styles of architecture. these styles can be categorized by their material of construction; the drystone architecture of kumbi saleh and the other cities of the ancient Ghana empire (in southern Mauritania), the classic mudbrick sudano-sahelian style of the "western Sudan" (Mali, Burkina Faso, parts of ivory coast and Ghana), the hausa-tubali architecture of the "central Sudan" (northern Nigeria and Niger) to the fired-brick architecture of the Kanem and Wadai (in chad)

The mosque of kumbi saleh in southern mauritania; at the apogee of the tichitt-walata architecture

Built around the end of the 11th century, this structure is one of the few buildings in the ancient capital of the Ghana empire that is relatively well preserved, constructed in the typical architectural style at kumbi that had evolved over millennia from the 4,000 year old neolithic sites of dhar tichitt and walata.

The tichitt-walata tradition was characterized by rectilinear and curvilinear houses built with of thin, rectangular stones, narrow rooms, schist wall plaques, rectangular and triangular wall niches and drystone floor-paving, with houses often grouped into a compound. All of these features became ubiquitous in west African architecture attesting to the primacy of the tichitt-walata architectural tradition in this region12

To this building style was added a maghrebian influence particularly the mihrab and the several supporting columns noticeable in the kumbi saleh mosque13 that was later reconstructed a number of times altering some designs14

A house in kumbi saleh with the typical wall niches and narrow rooms

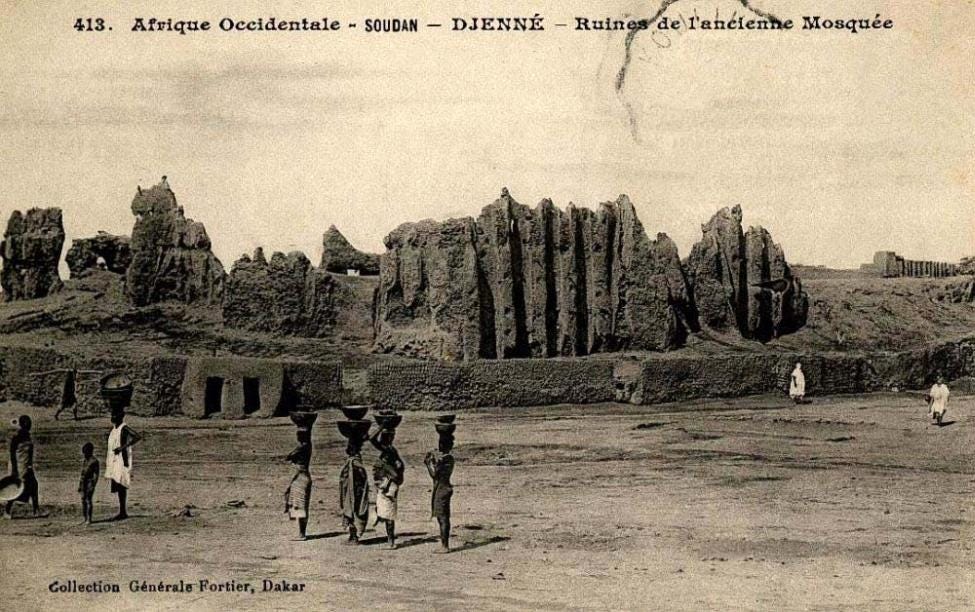

The Great mosque of djenne, mali

Until its near destruction in 1830, the Friday mosque of djenne was one of the largest structures in west africa, built in the 13th century by djenne king Koi Konboro, its mentioned in various writings about djenne both external and internal including al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan (written in the 17th century). The mosque was deliberately left to deteriorate by Massina king Seku Amadu in 1830 who owed his ascendance to his opposition against Djenne's elites for whom the mosque was symbolic

The present mosque is a reconstruction of the former and was completed in 1906 by Ismaila Traore and the architects of the djenne masons guild that included Madedeo Kossinentao, the final product was an almost true reconstruction of the original mosque and as architectural historian Jean-Louis Bourgeois writes "in its politics, design, technology, and grandeur, the mosque is largely local in origin" writing that contrary to common misconception, the mosque’s construction involved no French architect, French designs or measurements associated with French architecture, this can be seen by comparing the photos of the ruined mosque with the current mosque15

with its towering minarets, its pillars tapering over the roof, its imposing façade and height, there several architectural parallels that can be drawn eg the Sankore and Djinguereber mosques of Timbuktu, the Nando mosque of the dogon, the Kong mosque of the Watatra, the towering mansion of Aguibou tall at Bandiagara and the ubiquitous Tukolor-style façades of the djenne houses (eg the maiga house)

Doctor Rousseau (1893) and edmond fortier's (1906) photos of the old djenne mosque that had since been deteriorating for 70 years

The palace of kano

The 15th century, 33 arcre (500mx280m) palatial complex is the home of the king of kano and is perhaps the largest surviving palace in west Africa

Built in 1482 by the hausa sultan Muhammadu Rumfa (reigned 1463-1499), the Gidan rumfa (house of rumfa) its situated just outside the walled city of kano, in its own walled "surburb".

Enclosed within its 20-30ft high walls are a grouping of buildings that are entered through ornamental hausa gates, leading into an audience chamber, royal courtyards, apartments and several private rooms; many of the palace buildings have wide interiors and relatively high ceilings supported by the hausa vault (bakan gizo)16

while the hausalands at the time were a meltingpot of cultural influences emanating from the western sudan (Mali and Songhai empires) and the kanem empire, the palace itself was largely hausa in design with the typical hausa pinnacles, wall engravings and dagi motifs making it look like a hausa house that has been extended on a very large scale17

The Swahili architecture of the east African coast

The Swahili civilization is one of the most recognizable from central Africa, the Swahili are an eastern bantu-speaking group that settled along the east African coast by the middle of the 1st millennium AD in small fishing villages that gradually grew into mercantile cities with increasing trade primarily in gold from great Zimbabwe, manufacture of crafts like textiles and leatherworking and exporting primary products esp ivory during the classical era (1000-1500AD), most cities went into decline in the later centuries although some came under the suzerainty of the Oman empire after the 17th century

Swahili architecture is defined by historian Mark Horton as; "Swahili Islamic architecture is indigenous in character, expressing forms derived from local materials – timber (mangrove poles and hardwoods), fossil and reef coral, thatch and a ready availability of lime and plaster"18 and in earliest swahili cities like shanga, tumbe and chwaka the transition from earth and thatch dwellings to coral was a gradual process esp at shanga, where a small timber mosque was repeatedly reconstructed over time into a large coral mosque with vaults

Often times the mosques, palaces, tombs and the city walls were the first to be built in coral but later, both elite and non-elite houses were built with coral attimes with several stories and all with flat roofs or barrel vaulted domes but the rest were built with timber and used thatch for roofing

As historian J. E. G Sutton summarizes "the ruins at Kilwa, Songo Mnara and elsewhere on the coast and islands of Tanzania and Kenya, are therefore the relics of earlier Swahili settlements, not those of foreign immigrants or invaders ('arabs', 'shirazi' or whatever) as is commonly averred, although the mosques and tombs are by definition Islamic, they are not simple transplants from Arabian or the Persian gulf. Their architectural style is one which developed locally, being distinctive in both its forms and its coral masonry techniques of the Swahili coast"19

Husuni kubwa, A swahili king’s palace

This massive trapezoid complex measuring 70x100mx20m was built in the early 14th century a time of great prosperity and expansion in Kilwa from the increased prices of gold and the control of Sofala the entrepot to great Zimbabwe's gold that involved extensive building projects on Kilwa most notably under the reign of swahili sultan Al-Hasan bin Sulaiman (reign 1310-1333)

Al-hasan's palace includes stepped courtyards, a 2-m deep ornate swimming-pool, an audience hall, administrative section with several storage rooms and over 100 private rooms with vaulted roofs especially on its second floor. The interior has typical Swahili architectural features especially the sunken court, zidaka, niches for lamps, toilets and drainage systems

The famous globe-trotter Ibn Battuta was a guest at this palace and golden coin minted at kilwa by al-Hasan was found in great zimbabwe20

The comoronian-swahili architecture

Comoros and northern madagascar's city states in many ways mirrored those of the neighboring Swahili; comoronians speak the eastern bantu language of the sabaki group and are thus linguistic cousins of the Swahili21 , their architecture, trade patterns, islamisation, and maritine culture is similar to the swahili's

their buildings too featur the usual lime-washed coral (and basalt blocks), zidaka interior niches and carved doors22in addition to features unique to comoros eg the public square (bangwe)

The Kapviridjewo palace of iconi in comoros (also spelt Kaviridjeo/Kaviridjewe/Kavhiridjewo)

This 16th century building was the administrative building of the sultans of bambao, who resided in sultan Idarus' palace nearby23 The palace was constructed in the comoronian-swahili style that was increasingly appearing in late 14th and early 15th century official residences of comoro's rulers and was associated with increased contacts with and direct migration of Swahili elites from the east African coast especially kilwa24

Principal construction was with coral stone, lime and wood25, it was abandoned by the 19th century.

The Siyu fortress

Under the reign of king Bwana Mataka in the early 19th century, the swahili city of siyu became an important scholarly capital on the east African coast and possessed a vibrant crafts industry in leatherworks and furniture and book copying, bwana mataka was at war with the sultan seyyid said of Zanzibar whom he defeated thrice, it was during this period, that the fort was built likey in 1828, also constructed were his palace and a number of mosques26

It seems to have been later occupied by the Seyyid Said's forces after a negotiation with bwana Mataka's successor in the late 1840s but was then partly destroyed by bwana Mataka's son in 1863 to drive them out, it was then rebuilt by Sultan Seyyid Majid in the late 1860s27

While freestanding Swahili forts were rare (most notably the Husuni ndongo fort at kilwa), the majority of Swahili cities were defended by high walls with several watchtowers that made the whole city resemble a fort, but the Siyu fort used local architectural traditions as historian Richard wilding observed the fort's architecture shows "firm roots in the east African coastal tradition"28

The fort is a square edifice with two circular towers, its entrance has several benches on its sides leading into a courtyard with a Swahili-style mosque in the interior and several cannons were mounted along its sides in the past

The Madzimbabwe (Houses of stone); Great zimbabwe's acropolis, the great enclosure and the shona architectural tradition of the 'zimbabwe culture sites'

Great zimbabwe, the capital of the kingdom of zimbabwe, is the largest of the over 200 similar drystone settlements of the "zimbabwe culture sites" in south-eastern africa, the city consists of three main sections; the hill complex (acropolis) the great enclosure and the valley ruins

the walls weren't built for defensive purposes but instead "provided ritual seclusion from physical and supernatural danger" for the kingdom’s royals

While the ruins’ origin, builders and settlers have since the 1930s been recognized as belonging to the shona people (of the southern bantoid languages), the interpretations of the function of the different set of ruins at great Zimbabwe is still contested by archeologists

with archeologist Thomas Huffman taking a more general view of the architectural patterns of the zimbabwe culture sites (comparing with the ruins at Tsindi, Naletale and Danangombe) and shona traditions; he suggests that great zimbabwe was largely occupied from the 14th to the 16th century, and that the the acropolis was used as both the palace for the king that included the audience chamber, and the ritual center for rainmaking (following the shona religion where the kings doubled as sacred leaders of the state) while the "great enclosure" was used as the palace for the royal wives (following the 16th century Portuguese accounts)29

However, archeologist Shedrack Chirikure suggests that all sections of the city weren’t occupied simultaneously but rather in succession and that there were instead "centers adopted by successive rulers" (following the shona tradition of successions) and that the earliest of these centers was the "western enclosure" in the acropolis built between the 13th to the 14th century atferwhich the royal court moved to the great enclosure in the early 14th to mid 15th century, it was later abandoned after the mid16th century and lightly re-occupied at the end of the 19th century30

Without picking whose theory is accurate, ill instead describe the two sections of the city of great zimbabwe and include two other zimabwe cultures sites, ie; the city of Naletale and the Matendere ruins

The acropolis (hill complex) comprises a number of enclosures of which the western enclosure was the biggest and served as the palace area covering around 800sqm with a massive western wall over 80m long that was built with several towers that were originally topped with stone monoliths, to its east are a small number of enclosures that overlooked the great enclosure, these are then dissected by a number of passages leading to the recess enclosure and the eastern enclosure, there are several smaller enclosures

The great enclosure is a roughly elliptical structure with a circumference is 250 meters (820 feet) built with the finest q-style walls with chevron patterned courses rising up to 33 ft (11 meters) and is atleast 8 meters thick, there are three rounded entrances, one of which leads into a narrow paved passage that ends at a massive conical tower that is about 10 meters tall and nearly 6 meters wide

Naletale

The ruins here consist of an elliptical wall about 55 meters long, that is neatly coursed as is the most elaborately decorated among the zimbabwe culture sites, decorated with herringbone chevron, chessboard patterns. On top of the walls are nine battlements/towers on which four monoliths once stood

Naletale was part of the rozvi state from the 17th to the early 19th century and some interpretations of its function in relation to its use by rozvi royalty have been advanced31

Matendere

Most of the ruins are enclosed within a 550 ft long horseshoe shaped wall about 11ft thick and 15ft tall, atleast two monoliths were mounted on its top, in the interior are 6 enclosures separated by walls with several internal entrances

Matendere's relationship to great zimbabwe and its replication of the acropolis's (hill complex) spatial architecture has offered an interpretation of its function32

Conclusion

African architecture in its diversity, spatial arrangement, function or ostentatiousness is a peek into African history an society. It’s a product of african societies' interpretation of power and religion, its interaction with nature and with the foreign and its depiction of symbol and its functionality.

Mainstream studies of African architecture are handicapped by their selective look at a single region's architecture rather than a broader consideration of the continent's diverse architectural styles, this leads them to misattribute African constructions to foreign influences and regurgitate prejudiced rhetoric on African societies, fortunately there's since been a shift in how historians and archeologists interpret African architecture setting it firmly within the African context; rather than seeing it as an “oasis of civilization”, they now recognize it as the very nucleus of African states

i have made a patreon account to upload >1,500 photos of african ruins, cities, manuscripts and art and i will be writing longer essays on african history

Architecture, Power, and Communication: Case Studies from Ancient Nubia

by Andrea Manzo

The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art by László Török pg 174-176

Hellenizing Art in Ancient Nubia 300 B.C. - AD 250 and Its Egyptian Models by László Török pg 189-238

The Mosque Building in Old Dongola. Conservation and revitalization project by Artur Obłuski et al

Eastern African History by Robert O. Collins, pg 174

Darfur (Sudan) in the Age of Stone Architecture C. AD 1000-1750 by Andrew James McGregor

oxford handbook of African archeology by Peter Mitchell, Paul Lane, pg 806

The Archaeology of Africa by Thurstan Shaw, Bassey Andah et al, pg 619

Rock-cut stratigraphy: Sequencing the Lalibela churches, François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar etal

Ancient Churches of Ethiopia: Fourth-fourteenth Centuries by D. W. Phillipson

History of Ethiopian Towns from the Middle Ages to the Early Nineteenth Century, Volume 1 by Richard Pankhurst, pg 116

Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond by Martin Sterry, by David J. Mattingly pg 500-504

Bilan en 1977 des recherches archéologiques à Tegdaoust et Koumbi Saleh (Mauritanie) by Denise Robert-Chaleix, Serge Robert and Bernard Saison,

Recherches Archeologiques sur al Capitale de l'Empire de Ghana by Sophie Berthier

The History of the Great Mosques of Djenné by Jean-Louis Bourgeois

Islam, Gender, and Slavery in West Africa Circa 1500: A Spatial Archaeology of the Kano Palace, Northern Nigeria by Heidi Nast

Government In Kano, 1350-1950 by M. G. Smith, pg 131-

Islamic architecture of the Swahili coast by Mark Horton, in; the swahili world by Stephanie, LaViolette

kilwa A history by G sutton, pg 118

kilwa a history by g sutton, Behind the Sultan of Kilwa's “Rebellious Conduct” by Jeffrey Fleisher

the swahili by nurse and spear, pg 66

The Comoros and their early history by henry wright in, in; the swahili world by Stephanie, LaViolette

Archéologie des Comores: Maore & Ngazidja Institut des langues et civilisations orientales, pg 28

Islands in a Cosmopolitan Sea by Iain Walker, pg 42

Les Monuments et la mémoire by Jean Peyras, pg40

Siyu in the 18th and 19th centuries. by J de V Allen

Omani Sultans in Zanzibar, 1832-1964 Ahmed Hamoud Maamiry pg 9-17

a note on siu fort by richard wilding

Debating Great Zimbabwe by thomas huffman

Inside and outside the dry stone walls: revisiting the material culture of Great

Zimbabwe

by Shadreck Chirikure & Innocent Pikirayi

snakes and crocodiles by thomas huffman, pg 36-38

Snakes & Crocodiles: Power and Symbolism in Ancient Zimbabwe by Thomas N. Huffman pg 162-163