on the Nubian priests of Rome and the Moors of Spain

When the 12th-century West African scholar Ibrahim al-Kanemi moved to the city of Seville in Spain and became one of the most celebrated Andalusian poets, he wasn't the first from his region to visit the Moorish kingdom.

According to two separate accounts by Muslim and Christian chroniclers from the 13th century, West-African contingents allied with the Almoravid empire of Morocco played a decisive role in its conquest of Andalusia. The first account is provided by the historian Ibn Khallikan (d. 1282), whose description of the Battle of Sagrajas in 1086 between the Almoravid armies and the forces of the Castilian king Afonso VI, mentions that the former were initially losing the battle until the sūdān (west-African) horsemen joined the fray.

“This series of attacks and defeats did not terminate till the Emir of the Muslims [the Almoravid ruler] ordered the sūdān who formed his domestic troops to dismount. Four thousand of them got off their horses and penetrated into the midst of the fight. They stabbed the enemy's horses and made them rear under the riders, so that each steed separated from its fellow. Alfonso overtook a sūdān whose stock of javelins had been spent by darting them off, and meant to cut him down with his sword. The sūdān closed with him, seized on the bridle of his horse, drew a dagger from his belt and struck it into his thigh.”

After this, the tide of war turned against the Castilian armies and they were annihilated. The general chronicle of Spain (Estoria de España), which was commissioned by the Castilian king Alfonso X (1252-1284), understandably chooses to skip over the details of this battle.1 The chronicle instead focuses on other battles where the Castilians were relatively successful, such as the Almoravid siege of the Spanish city of Valencia in 1093-4:

“King Bucar [the Almoravid general] arrived from Tunis and disembarked at the port of Valencia with an extraordinarily large force of thirty-six Moorish kings; and he brought with him a black Moorish woman [mora negra], who had 300 black Moorish women with her, and they all of them had their heads shaved, apart from a tuft which each of them had on the top of her head. This was because they came as if on a pilgrimage and to seek pardon. They were well armed with cuirasses and with Turkish bows.”2

Despite putting up a spirited fight, the defenders managed to push back the Almoravid force, and Valencia wouldn't fall until a decade later in 1102.

In the decades following these battles, the diasporic community of West Africans in Andalusia had grown significantly, such that by 1154, the Andalusian Geographer al-Zuhri reported that some of the “chief leaders” in the Ghana empire traveled to Andalusia, a few decades before Ibrahim al-Kanimi would move to Seville.3 The presence of these West Africans in Muslim Spain would leave its mark in the 13th-century artwork of the kingdom of Castille that depicted the cosmopolitan society of the Moorish kingdom, showing dark-complexioned Africans playing chess and fighting alongside the Almoravids.4

Moorish noblemen and servants playing chess, Chessbook of Alfonso X the Wise, fol. 22r. Spain (1283).

Battle between the Castilian armies and the armies of Muslim Spain, miniature from the Cantigas de Santa Maria of Alfonso X the Wise,13th Century, Spain. Getty Images.

The history of Africa's exploration and knowledge of the Old World is much better known today than a half-century ago when the continent was erroneously thought to have been isolated from global history. There is now a growing body of evidence for the presence of Africans across much of the old world since antiquity, and an emerging field of literature focusing on the activities of these intrepid African travelers in the distant places they chose to visit and settle.

The lengthy career of the 16th-century Kongo diplomat Antonio Vieira for example, illustrates the dynamic nature of Africa's diasporic community. Born in Kongo in 1506, Antonio was one of the students sent by King Afonso Mvemba a Nzinga to the convent of St. Eloy in Lisbon in the 1520s. He later became the ambassador of King Pedro Nkanga a Mvemba [r. 1543-1545], and settled in Lisbon as the 'royal factor' of King Diogo I Nkumbi a Mpudi [r. 1545-1561].

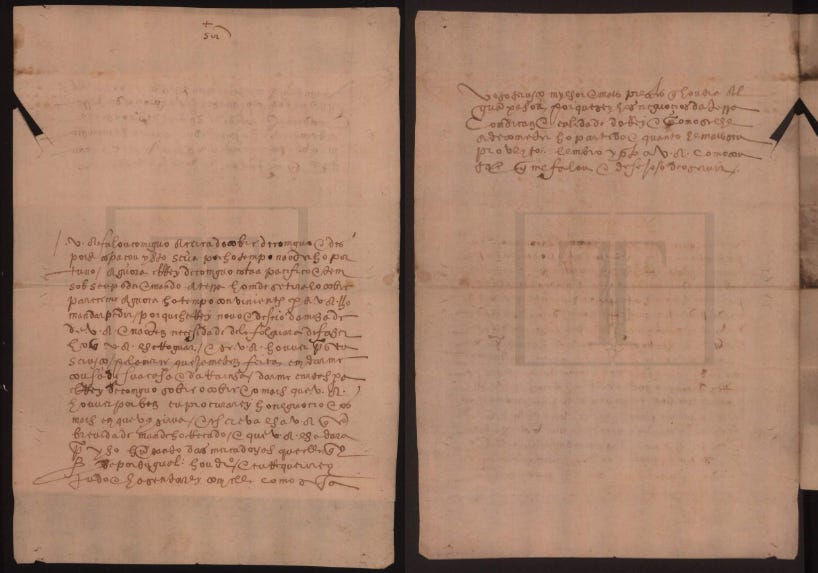

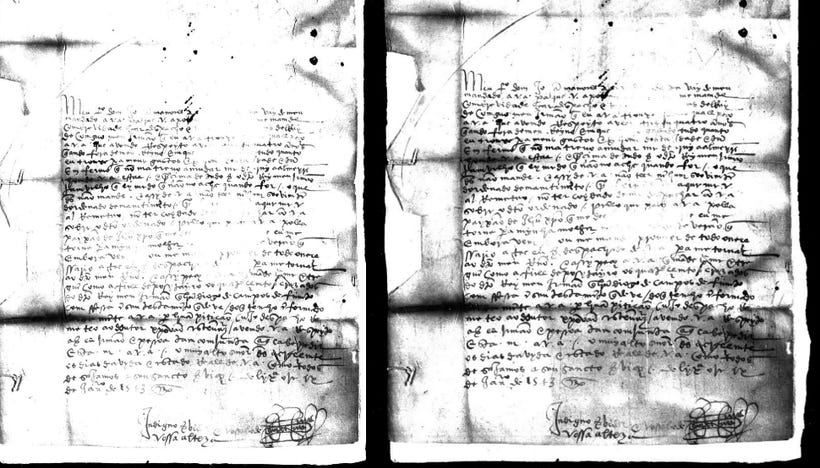

Letter by Antonio Vieira about copper mining and trade in Kongo, 1566, PT/TT/CART/878/219. Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo.

According to a charter issued by the secretary of King Diogo, as well as other contemporary correspondence, Antonio was responsible for collecting and receiving debts, exchanging currencies for embassies from Kongo, and legitimizing the children of Kongo's elites abroad. These activities required the presence of a resident factor to prove the credentials of the persons involved. Antonio also composed a number of documents about Kongo’s politics and a brief autobiography, which are all included in the corpus of extant manuscripts from the central African kingdom.5

Letter by Diogo’s envoy to Lisbon 1543, mentioning a creditor whom Antonio Vieira had been instructed to collect money from. PT/TT/CC/1/73/41. Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo.

The international activities of such African travellers across the old world were therefore more extensive than the brief mentions of their presence in external accounts would suggest. Some of the diasporic Africans were engaged in intellectual exchanges, such as the Ethiopians of Rome and the West Africans of Medina, others were preoccupied with trade such as the Swahili of India, while others were highly regarded as priests who played a central role in the spread of one of the ancient world's most widespread religions.

At the height of Rome in the first century of the common era, the Egyptian goddess Isis became one of the most popular deities across the empire. Among the most important centers of the Isiac religion were the towns of Philae (Egypt) and Herculaneum (Italy), where Nubian/aithiopian priests and pilgrims feature prominently in the documentary and archaeological record.

The worship of Isis was arguably the most widely practiced religion originating from Africa, having been carried by itinerant merchants and other travelers from the Nile valley to places as far as Spain and the Black Sea region. The evidence from Philae and Herculaneum indicates that some of these missionaries of Isis were Nubians who had for centuries worshipped the deity in the kingdom Kush, and recognized her as one of the most powerful deities of their Pantheon.

The history of Nubian priests of Isis in the Roman world is the subject of my latest Patreon article,

Please subscribe to read about it here:

Panel painting from Herculaneum depicting an Isiac ceremony. The congregation includes aithiopian priests, attendants, dancers, and worshippers. inv. no. 8919, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy.

Primera crónica general de España que mandó componer Alfonso el Sabio y se continuaba bajo Sancho IV en 1289, Alfonso X (King of Castile and Leon), edited by Ramón Menéndez Pidal, pg 557-558.

Black Women Warriors in the Muslim Army Besieging Valencia and the Cid's Victory: A Problem of Interpretation by E Lourie

Medieval West Africa: Views from Arab Scholars and Merchants by Nehemia Levtzion, Jay Spaulding pg 25

Image of the black in western Art, Volume 2, issue 1, pg 78

Monumenta missionaria africana II by Brásio António, pg 149-150, 240-241, 330, 543-546, Africa: Tradition and Change by Evelyn Jones Rich, Immanuel Maurice Wallerstein pg 200, Early Kongo-Portuguese relations by John K. Thornton pg 187, 191, n.49

Thank you Mr Samuel, always looked fwd to your articles.