One woman's mission to unite a divided kingdom: Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the restoration of Kongo. (1704-1706)

Race, theology, and an African church.

The kingdom of Kongo appears unusual in popular understanding of pre-colonial African societies; A 600-year old kingdom in central Africa, with a unique Christian tradition and its noticeable Iberian influences, but with a history firmly rooted on the continent as a fully independent regional power. While an image of a Muslim or Coptic pre-colonial Africa has come to be accepted, the one of a catholic African state has proved difficult for some to reconcile with their preconceptions of African history.

But just like the spread of Axial religions across most of Africa (and indeed, many of the ‘Old world’ societies), Kongo adopted Christianity on its own terms, syncretizing the religion within the structure of Kongo's society and making it one of kingdom's institutions. When internal political processes broke the kingdom apart and foreign priests tried to threaten the independence of Kongo's church; it was Kongo's citizens, led by a charismatic prophetess named Beatriz Kimpa Vita, who rose up to the challenge of reuniting the kingdom and affirming the independence of its Church.

This article explores the Politico-religious movement of Beatriz Kimpa Vita and its role in restoring the Kingdom of Kongo and securing the independence of Kongo's Christian tradition as an African religion.

Map of a divided kingdom of Kongo in 1700

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

The warring dynasties of Kongo

In 1678, Kongo's capital city of Mbanza Kongo , once home to over 100,000 inhabitants, was abandoned as the Kingdom descended into a protracted civil war. The two most powerful royal houses; the Kinlaza and the Kimpanzu couldn't dominate the other, despite the latter having defeated a Portuguese invasion in 1670. The Kinlaza house was itself split between three main figures; king Pedro IV (who also had Kimpanzu lineage), the rival king João II, and the Queen regnant Ana Afonso;1 all controlling fragments of what was once a large unified kingdom.

The toll of their civil war was significant on Kongo's citizenry primarily because of the need to mobilize large armies that served under each rivaling ruler. The size of the armies required were considerably large, with as many as 20,000 soldiers under the command of Queen Ana and her allies in 1702, these armies also required a support train carrying supplies and provisions, as well as cooks, nurses and field companions, that numbered just as large as the main army itself, with as many as 50,000 people being mobilized. The movements of these large armies were attimes destructive to the countryside as campaigns often outlasted their provisions forcing the soldiers to rely on the stored harvests in the villages.2

Another negative effect was the uptick in external slave trade as a consequence of the wars. While acquisition of slaves was never the primarily objective of the rivaling rulers, who were above all else hoping to restore central authority, the accumulation of prisoners of war always followed after a major war. Many of these were retained locally and gradually integrated as soldiers, attendants and later as subjects , but a sizeable proportion were also sold through long distance routes that ultimately led to the Atlantic ports.3

While the territory dominated by Kongo had not been a significant exporter in the 15th and 16th century, the first decade of the 18th century saw it contribute just under half of the slaves going through Luanda between 1700-1709 (an estimate of about 1,000 a year4), and enslaved catholic baKongo (ie; citizens of Kongo5) begun to appear in American plantation colonies, which had been virtually impossible in the previous centuries, as the kings of Kongo went to great lengths to repatriate their baKongo subjects from as far as Brazil, when they had been wrongfully enslaved.6

King Pedro was the most determined among the rivaling contenders to reoccupy the capital and restore Kongo as a centralized Kingdom, but an earlier attempt to settle inside the city after his coronation in 1694 had to be aborted when João's forces threatened to attack . Pedro had retreated to his capital, but sent advance columns in camps of several thousand subjects under two of his officers to re-occupy the capital, the first camp was under Pedro's head of administration; Manuel da Cruz Barbosa and the second was under his captain general Kibenga.7

It was in the latter group that became a cause of concern for Pedro, due to the growing mood of religious fervor among the baKongo that threatened to split Kongo's church, and produced popular figures whose religious movements also carried political overtones connected with the reoccupation of the abandoned capital city, and an end of the incessant conflicts.

The church in Kongo: creating an African religious institution.

The church had been a fully Kongo-lese institution from its inception in 1491, and was largely shaped by Kongo's kings as well as educated baKongo laypeople who disseminated religious education in church schools across the kingdom, ensuring that Kongo's form of Catholicism was thus fully syncretized into Kongo's customs and religious beliefs.8 The baKongo Christians, who had adopted the religion on their own accord, therefore retained pre-Christian lexicon such as nkita (a term for generous deceased ancestors) and kindoki (the religious power to do good or bad),as well as the elevated position of ancestors, in the process of indigenizing their church.9

For example, in Kongo's Catholicism, the main Christian figures; such as Jesus, Mary and the saints, were powerful nkitas, and since they had no living descendants they were thus nonpartisan, universally positive figures who were above petty concerns and were unwilling to do evil on behalf of their descendants unlike the morally ambiguous recently-deceased ancestors who had living descendants.10

Since the most important religious rites (especially sacraments like baptism) could only be performed by ordained priests (clergy), Kongo's monarchs tried to create their own clergy by educating baKongo bishops, a plan that opposed by the Portuguese, who wanted to retain some measure of control over Kongo's church however miniscule this control actually was. Kongo nevertheless managed to obtain Vatican approval for the establishment of an independent episcopal see (seat of the Bishop) that was founded at Mbanza Kongo in 1596. (the city henceforth renamed São Salvador after its main cathedral).11

Mbanza Kongo (São Salvador) by Olfert Dapper in 1668

Containing the foreign clergy into the Kongo church.

Kongo's kings effectively retained control of the church under local authority by strategically altering the source of the priests depending on how well they served their interests. The kingdom thus saw the arrival of secular and regular priestly orders from 1491, including; the Jesuits in 1548, the Franciscans in 1557, the Carmelites in 1585 and the Capuchins in 1645, but these (foreign) priests' work was confined to providing sacraments; often only appearing annually for baptisms, marriages, and the like, while most of church activities and teaching was done by the baKongo laity (non-ordained members of the church).12

But after São Salvador’s abandonment in 1678 and the Bishop’s shift to Luanda, the capuchin priests increasingly insisted that they had to be respected as independent religious authorities by all baKongo including the nobility and kings, in a sharp break from the previous priests who strictly observed Kongo’s laws and customs. The capuchins leveraged their kindoki through their selflessness, poverty and chastity, to buttress their claims of religious authority, unlike previous priestly orders that had fallen short of all three qualities in the eyes of the baKongo. They also clashed with the baKongo laity on a number of issues, for example, while the former regarded spiritual possession as an acceptable form of revelation, the capuchins regarded all forms of possession as suspect, and often said possession was solely derived from the devil.13

In another notable incident, a capuchin priest at king Pedro's court tried to get his friend, an Aragonese layperson, to violate protocol by not observing Kongo customs in greeting the King; claiming that since the Aragonese as a fellow European like himself, he should not follow Kongo's customs. This caused a bitter standoff with king Pedro who insisted that the guest must observe protocol, and the king ultimately prevailed over the priest forcing the Aragonese to be expelled. This incident damaged the reputation of the capuchin's kindoki in the eyes of the baKongo who begun to think that the priests were using the power selfishly (ie; negatively), in this case; to acquire special privileges by virtue of being European, which the proud baKongo could never tolerate. (negative kindoki is called ndoki and is equivalent to witchcraft).14

Politico-Religious movements in early 18th century Kongo and the birth of Beatriz

As the capuchin’s religious authority was being called into question, reports were circulating that a woman named Dona Beatriz, who was in Kibenga's camp, had seen a vision of Mary. In this vision, Mary told her that Jesus was angry with the Kongolese and that they must ask his mercy, that they must re-occupy the capital and end the incessant wars. Her movement soon caught on among the commoners in Kibenga's camp and thousands begun following it.15

Similar movements had emerged in the same region, including one led by a man whose preaching about his reflationary dreams of a small child telling him that God was going to punish the baKongo if they did not occupy Sao Salvador as quickly as possible, and another led by a woman called Apollonia Mafuta, who recounted a vision in which Jesus was angry at King Pedro and his subjects for not coming down from his capital to restore the city. She took her message to king Pedro's capital and and was invited by the king, who chose not to arrest her, despite the advice of Father Bernardo; who was the capuchin priest active in Pedro's court at the time.16

Dona Beatriz was born in 1684 to a minor noble family, unlike all baKongo of her status who received their education early in their youth, she was only partially literate. Sure about her religious gifts, she joined an (informal) religious society and became one among many informal minor religious figures in Kongo whom people attimes consulted (outside the formal Church practice) for social remedies —but in a Christian context. She got married under traditional custom, but later divorced —which was permissible in Kongo as long as the marriage hadn't advanced to the stage of being formally united by the priest.17

Illustration of a Capuchin priest performing a catholic wedding in Soyo, Kongo kingdom, 1747

Beatriz’s Antonian movement

Late in 1704, Beatriz fell ill and is said to have led to her death and rebirth as saint Anthony. Her first action was to go straight to King Pedro's residence and rebuke him for not occupying the capital and not ending the wars, saying if he lacked the will to restore the city, she would do it herself. She also denounced Father Bernado as a ndoki, who didn't want baKongo saints like Mafuta and herself because of his jealousy.18

Beatriz preached against all forms of greed and jealousy and the misuse of kindoki by the capuchin priests and some of the baKongo. Her preaching mostly revolved around three main points; that saint Anthony (Kongo's patron saint) was the most important saint in Kongo's church; secondly, that Jesus was angry with the baKongo for not reoccupying the old capital; thirdly, she urged her followers to be happy since her rebirth as saint Anthony meant that the baKongo could have saints.19

Her message begun to be received by some of the baKongo commoners who were questioning the activities of the capuchins, the latter of whom, since their damaged reputation over the protocol incident, had doubled down in exaggerating their clerical credentials by attimes claiming special privileges in religious matters solely because the saints were of European origin. This was in direct opposition to the baKongo's image of the non-partisan saints who had no living descendants/relatives (whether European or baKongo) and the capuchin's bold claims were therefore very poorly received.20

In direct response to the capuchins, Beatriz reinterpreted the nativity story by saying that the event took place in Kongo's capital Sao Salvador, that the infant Christ was baptized in the city of Nsudi and that st. Anthony was from the Vunda lineage of Kongo's nobles. She also made a new commentary on the Marian hymn 'Salve Regina' by providing its full translation into kikongo, and emphasizing the status of st. Anthony in it. 21

She also elaborated on the question of race in a novel way using a colour scheme that fitted baKongo concepts. She contended that since white was considered the colour of the deceased; who were thought of as dwelling around bodies of water where white rocks called fuma were found, that the the Europeans could thus be identified as originating from fuma. And since black was considered the colour of the living world and associated with life, and since the black-coloured cloth worn in Kongo came from the Nsanda tree, she thus identified the tree with the origin of the baKongo. The blood of Christ was on the other hand, identified as originating from the takula wood, which produced the red dye used in Kongo's marriages.22

Beatriz’s novel conception of race had been directly influenced by the capuchin's attempts to introduce and then leverage their European concepts of race in Kongo's church politics. Its difficult to tell if either the capuchin's concepts of race or Beatriz's had any lasting impact, as the baKongo's understanding of “race” (or rather; population groups) was not based on skin colour, but on their geographic origin. For example, the Europeans who had arrived on whale-like ships were called mundele (ie; whale) rather than mpembe which meant white.23 The term mpembe was instead associated with the world of the ancestors and was only rarely conflated with (living) Europeans whose lands many baKongo envoys had been to. The conflation between mpembe spirits and Europeans was only reported in regions where European presence was rare, unlike in Kongo.24

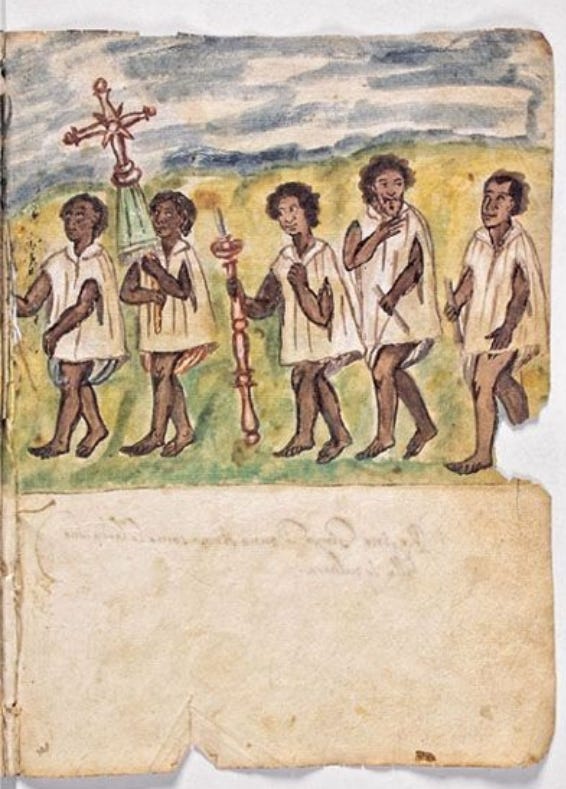

Procession of faithfuls in angola, by Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi c. 1668

Beatriz’s pilgrimage through Kongo and the prophetess’ capital

King Pedro referred Beatriz to the capuchin priest Father Bernardo for examination, sending his own secretary and relative Miguel de Castro who was also a church master (a high position among laypeople), to reassure Beatriz of her security. Beatriz's teachings were examined by Bernardo whose angry rhetorical line of questioning ended with him strongly reprimanding both her and de Castro (for supporting her). Bernardo was convinced she was possessed by the devil following his European interpretation, while de Castro thought she could have been possessed by st. Anthony following his Kongo interpretation. Bernado reported about his interview with Beatriz to king Pedro, but the latter skillfully rebuffed the priest's advice to arrest her, by reminding the priest about Kongo's precarious political realities.25

Beatriz then took her movement across Kongo, first going to da Cruz Barbosa's camp, who nearly had her executed had it not for king Pedro instructing him against it, she then went to the rival king Joao's capital —ostensibly to acquire a relic, but she was eventually expelled (although not before claiming to have acquired the relic), she had nevertheless gathered a large following from among the commoners that were subjects of both regions, who then chose to travel with her to re-occupy Kongo's capital.26

Beatriz reoccupied Sao Salvador in November 1704, symbolically accomplishing what Pedro had failed to do. King Pedro's captain general Kibenga, whose camp was near the city, seized the opportunity to support Beatriz's followers with supplies and thus effectively rebelled against his king. Beatriz sent some of her followers as disciples called 'little Anthonys' across Kongo to preach her message; which was received by the commoners but rejected by the nobles. The effect of the little Anthonys soon became disruptive to the clergy's work and the baKongo begun breaking their well-established sacrament of baptism, because her message was that God knew people's intention in their hearts. More followers flocked to the capital such that its population had nearly recovered its height in the early 17th century.27

As the movement acquired a political character, king Pedro begun to move against it. Gradually descending from his capital in 1705-1706, he advanced against the Sao Salvador-based followers of Beatriz and against his rebel general Kipenga who guarded them. During this time, Beatriz had developed a relationship with one of her followers named Barro (a sort of second in command) and was pregnant in mid-1705 giving birth in early 1706. This birth however, greatly undermined her religious standing especially in contrast to the reputedly chaste capuchins.28

Bernado’s sketch of Beatriz Kimpa Vita

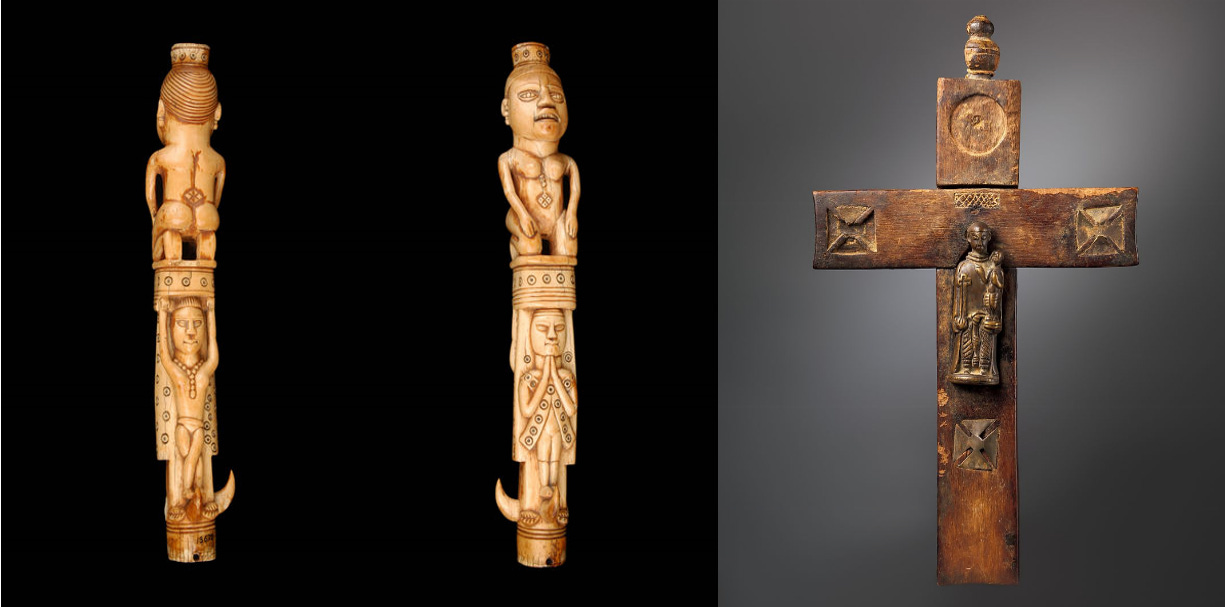

figures of st. Anthony and the infant christ made by baKongo artists; (Minneapolis institute of art, Met museum). The first figure depicts the saint with a netted cape typically reserved for Kongo nobility, while the latter places the saint on a traditional kongo staff of office.

Beatriz’s death and the rebirth of Kongo

When Queen Ana's envoys to king Pedro discovered the couple and their baby, they took the trio to king Pedro, who after several days of deliberating with his council and the capuchin priest Bernado, decided that Beatriz and Barro were to be burned at the stake29, while the baby was to be adopted by another family. On her part, Beatriz believed she was only guilty of not being chaste but maintained that she innocent with regards to her message, in which she was steadfast to her death on 2nd July, 1706.30

King Pedro launched his final assault against Kibenga’s army in Sao Salvador in February 1709, allying with the forces of Queen Ana's successor Alvaro to create a large army of 20,000 soldiers, they defeated Kibenga's army and permanently occupied the capital. Pedro then moved his forces north to the rival king Joao II's territory and they defeated the latter's forces, giving Pedro control over most of Kongo's core territories31. Recognizing the permanence of Kongo's irreconcilable royal houses, king Pedro arranged for a rotation of Kings from both the Kinlaza and Kimpazu houses, which would remain in place for much of the 18th century, and the city retained its symbolic importance well into the 20th century; when it was renamed Mbanza Kongo.32

Sao Salvador remained the capital of the restored kingdom largely due to Beatriz's movement, some of its ruined churches were rebuilt and its population was estimated to be about 35,000 in the mid 18th century33. Besides restoring the capital, Beatriz's most visible legacy was in the further indigenization of Kongo’s Christianity as seen in the visual and material manifestations of her movement. The years following her movement saw the emergence of the artistic representation of crucifixes with stylized depictions of Jesus wearing Kongolese clothing, as well as various figures of st Anthony dressed as a Kongo noble, and depictions of baKongo in praying stances. 34

Kongo crucifixes from the 18th/19th century (minneapolis institute of art, private collection) depicting Jesus and ancillary figures wearing Kongo’s mpu caps35, the second figure of Jesus wears a loincloth resembling Kongo’s libongo textile patterns.

19th century Ivory staff finial (quai branly 73.1991.1.1 D) depicting Kongo figures in praying and crucifixion stances, Saint Anthony on an 18th century Kongo crucifix (metropolitan museum)

the cathedral of Sao Salvador in Mbanza Kongo, Angola, built in the mid-16th century and currently the only ruin left of the original city, it was restored several times including during Beatriz’s occupation of the city in 1704-636.

Conclusion: positioning the Antonian movement and Kongo’s church in African history

Beatriz's movement shows that far from being a divisive foreign intrusion used by the "semi-colonial" elite but opposed by the rest of the people, Kongo's church was a fully indigenous institution situated at the center of the baKongo's identity. It was baKongo commoners and peasants who joined Beatriz’s politico-religious movement to protect the independence of their unique Christian tradition against their seemingly passive rulers and interloping clergy.

Beatriz's decisive role in the restoration of the kingdom of Kongo and the legacy of her religious movement, makes her one of the most influential women in African history, and her story highlights the often overlooked but salient contribution of women in African religions.

Is Jared Diamond’s “GUNS, GERMS AND STEEL” a work of monumental ambition? or a collection of speculative conjecture and unremarkable insights.

My review Jared Diamond myths about Africa history on Patreon

If you liked this article, or would like to contribute to my African history website project; please donate on my Paypal

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 205-208)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 95-98)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 99-104)

There’s no disambiguation that shows where exactly the slaves sold at each port came from, but the port of Ambriz which was in Kongo’s territory wasn’t exporting any slaves until 1786; this figure is taken from “The Atlantic Slave Trade from Angola by Daniel Domingues da Silva”, pg 121

i’m using baKongo for simplicity, the correct word is Essikongo. baKongo simply means speakers of the kikongo language and not all of them were under the kongo kingdom

Slavery and its transformation in Kongo by LM Heywood

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 91-92)

Afro-Christian syncretism in the Kingdom of Kongo by J.K.thornton pg 56-59)

Kongo political culture by Wyatt MacGaffey pg 141, 12)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 117)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg 108)

Afro-Christian syncretism in the Kingdom of Kongo by J.K.thornton pg 63-65)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 124-125)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 88, 113)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 105)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 107-109)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 17, 54-56, 28)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg pg 110-111)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 112)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 113)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 114-117)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 160-161)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 27)

Kongo political culture by Wyatt MacGaffey pg pg 27-29)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 120-128)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton 134-137)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 140-154

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 163-7)

this could be the only documented case of this sort of punishment in kongo; it was likely influenced by the capuchins since it was still popular in europe at the time, only being outlawed in Britain in 1790

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 168-183)

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg pg 197-202)

A History of West Central Africa to 1850 by John Thornton pg pg 245)

Africa's Urban Past By R. Rathbone pg 75

The Art of Conversion by Cécile Fromont pg 75-108)

The Art of Conversion by Cécile Fromont pg 94

The Kongolese Saint Anthony by John Thornton pg 157

Always on point and full of interesting information great read as usual, I had no idea that Catholicism was so deeply entrenched and aligned with that of the indigenous customs of the Bakongo kingdom. Not so different from Islam in Mali and a'lot of West African Muslim Nations interesting to think about, also makes me wonder had Christian Ethiopia and Bakongo ever by chance crossed paths how they'd interact.

‘The baKongo Christians, who had adopted the religion on their own accord, ...’

This seems a difficult statement to back up. The Portuguese, as were many European colonizers, quite brutal in their treatment of slaves and enforcement of Christianity. Why would it be any different in Kongo?