Perspectives and outcomes of Africa's age of exploration

Nearly a century after the Kushite envoys of Queen Amanirenas visited the court of Augustus in 22-20BC, a pair of Roman centurions was sent on a reconnaissance mission to Kush in 61-63 CE to gather intelligence for a planned campaign against the kingdom by the Emperor Nero.1

While Nero ultimately decided against the expedition after assessing Kush's strength, these initial exchanges resulted in increased contacts between Rome and Kush, which involved the exchange of embassies and the travel of Kushite envoys and Isiac priests across the Roman world, from Philae in Egypt to Herculaneum in Italy

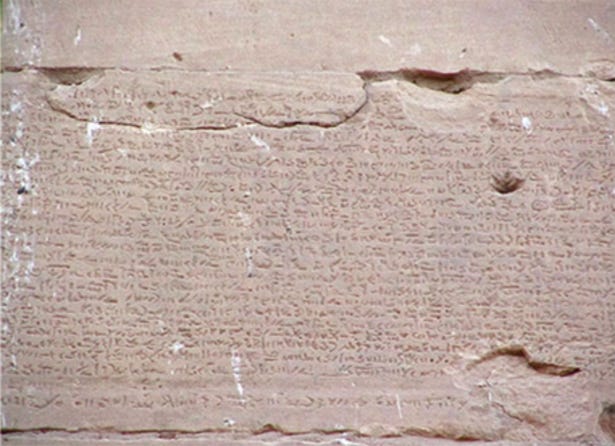

A 26-line inscription on the Gate of Hadrian records the Nubian envoy Sasan’s participation in rites held on the island in A.D. 253. Image and caption by Solange Ashby. The inscription includes prayers for Sasan’s success in his diplomatic mission to Rome, which also involves matters of direct concern for the cult of Isis, and a safe return to Meroe.2

Panel painting from Herculaneum. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. no. 8924, depicting aithiopian (Nubian) priests as central figures in an Isiac ceremony.

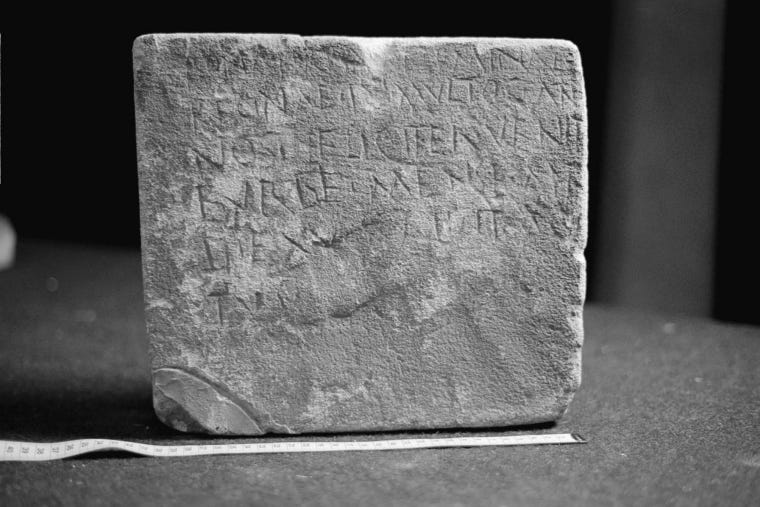

Latin inscription made by Acutus, the Roman envoy to Kush in the 3rd century, found at Musawwarat al-Sufra (Nubia), SMBK inv. no. 9675.3

The arrival of Ethiopian envoys and pilgrims in various European courts and pilgrimage sites between the 14th and 16th centuries also resulted in increased contacts between the African kingdom and its Latin co-religionists. This period of mutual exploration produced some of the earliest African perspectives of European societies and cultures.

In response to the attempts by the Portuguese Catholic clerics to subordinate the Ethiopian church, the Ethiopian envoy Sägga Zäᵓab authored a treatise titled The Faith of the Ethiopians in 1534, which advocated for the co-existence of the different Christian sects and the continued independence of the Ethiopian Church:

“It would be much wiser to welcome in charity and Christian love all Christians, be they Greeks, Armenians, Ethiopians, or those belonging to any other of the seven Christian churches. They all should be allowed to live with and move among other Christian brothers, because we are all sons of baptism and share the true faith.”4

Illustration depicting the Ethiopian monastery in Rome known as Däbrä Qeddus Estifanos (Santo Stefano degli Abissini), made in the 1750s by Giuseppe Vasi

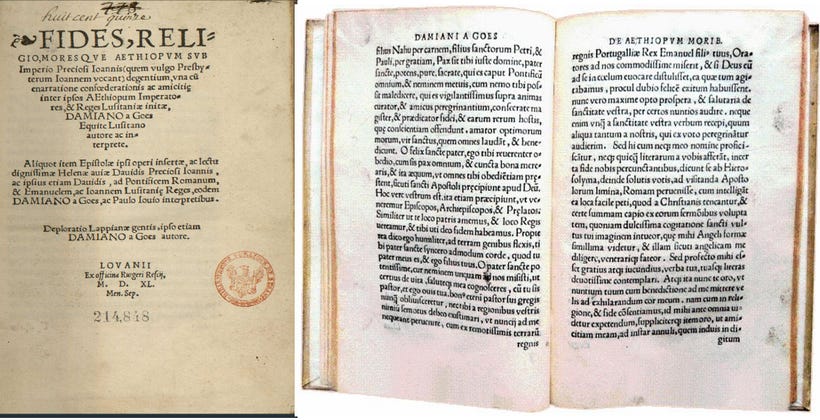

Sägga Zäᵓab’s ‘The Faith of the Ethiopians’, translated and published in 1540.

From the end of the Middle Ages to the dawn of the colonial period, African travellers in various capacities from virtually all parts of the continent visited most of the Old World from Western Europe to East Asia and Russia, as outlined in dozens of my essays on the General History of African explorers.

The ambassador Antonio Emanuele Ne Vunda of the Kingdom of Kongo and the embassy of Hasekura Tsunenaga of Japan. Painting by Agostino Taschi. ca. 1616 in the Sala dei Corazzieri, Palazzo del Quirinale., Rome

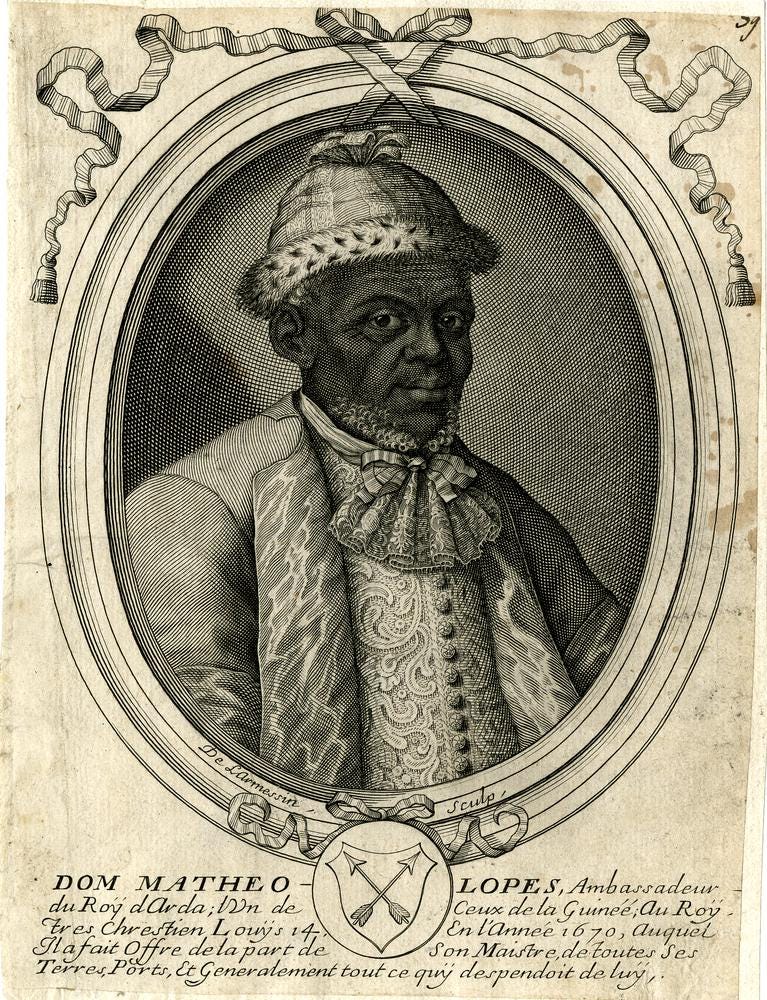

Portrait of Matheo Lopez, Ambassador of the Kingdom of Allada to France in 1670.

During the 19th century, some of these intrepid explorers produced lengthy accounts of their journeys, and many acted as cultural translators and ‘modernisers’ who played a critical role in African attempts to mitigate or modify the tide of European imperialism that was engulfing the continent in the closing decades of the century.

In southern Africa, one such African traveller was the Xhosa nobleman Tiyo Soga (1829-1871), whose nearly decade-long stay in Scotland between 1848 and 1857 influenced his pragmatic approach to western acculturation, advocating for a selective and controlled relationship with the European Other.

“I would ask my African-born friends here present to go to London, to Edinburgh, to Glasgow. Let them watch breakfast, dinner, and closing hours when their thousands of labourers are relieved of their toil; let them see the pale, sickly, careworn factory girls who have no hope of life but in that imprisonment, and they will thank God for having been born in the free air of the desert.”5

Soga also advocated for the continued independence of African rulers, many of whom sent several embassies directly to London, hoping to achieve a diplomatic alternative to armed resistance against colonization by the encroaching British Cape Colony and the Boer Republics.

Between 1853 and 1895, at least seven kingdoms in southern Africa sent embassies to the court of Queen Victoria, five of which successfully met with the monarch and were treated as official envoys of what were then independent states.

The varying outcomes of these meetings would have important repercussions for the nature of colonial expansion experienced by the different societies of southern Africa in what is today Botswana, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Eswatini, and Lesotho.

The perspectives of these South African explorers and the consequences of their diplomatic negotiations are the subject of my latest Patreon article:

Please subscribe to read more about it here and support this newsletter:

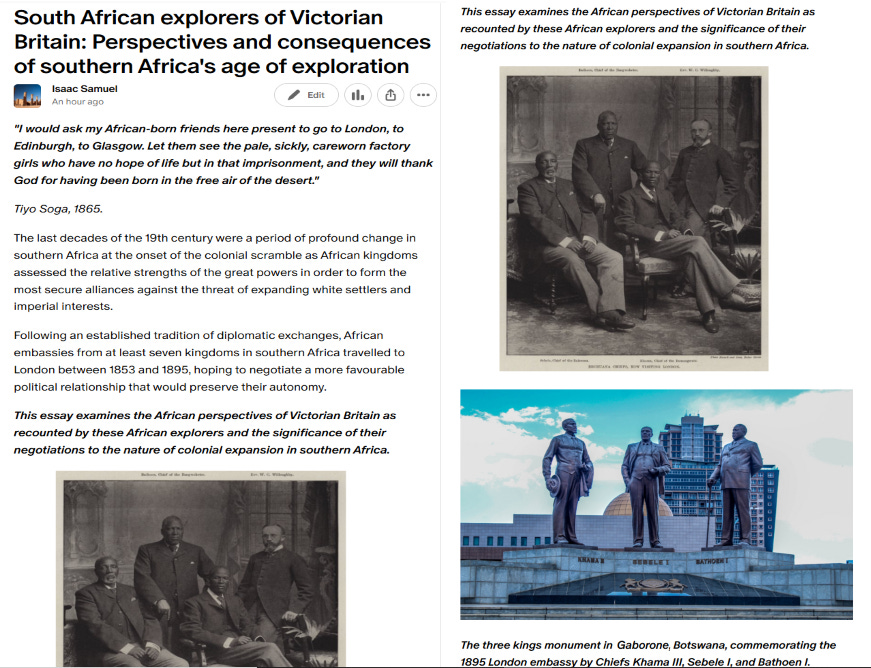

‘The three kings’ monument in Gaborone, Botswana, commemorates the 1895 London embassy by Khama III, Sebele I, and Bathoen I, who secured Bechuanaland's autonomy from Cecil Rhodes’ Rhodesia and the Cape Colony.

The Kingdom of Kush by L. Torok pg 451-455, Headhunting on the Roman Frontier by Uroš Matić pg 128-9

The Demotic Proskynema of a Meroite Envoy by Jeremy Pope

The Christian epigraphy of Egypt and Nubia by Jacques van der Vliet, pg 381-385

Damião de Góis by Elisabeth Feist Hirsch pg 148-151

The Journal and Selected Writings of the Reverend Tiyo Soga by Tiyo Soga pg 190

Please Samuel dont cut content for the sake of brevity like you said on twitter. Your content probably attracts people who dont see reading long in depth content about African history as a chore but rather as a pleasure.