Revealing African spatial concepts in external documents: How the Hausalands became "cartographically visible".

Interpreting an 18th century Hausa scholar's map of his Homeland.

During the mid-14th century, the globe-trotter Ibn Battuta set himself on a journey through west Africa, into the region from where many his peers —the early scholars, merchants and travelers of west-Africa who crisscrossed Mediterranean world— originated. Battuta described various west African states and regions using local ethnonyms and toponyms that he derived from his west African guests, providing important first-hand information that made much of west Africa “cartographically visible” on external maps, except for one region; the Hausalands.

The Hausalands only appear suddenly and vividly in external accounts beginning with Leo Africanus in the early 16th century, and by the 18th century, an astonishing cartographic depiction of the Hausalands with all its endonyms for its states and rivers was made by one of the region’s scholars for a foreign geographer. The stark contrast between the apparently invisibility of the region during Ibn Batutta’s time versus its cartographic visibility after Leo Africanus’ time was the product of a process in which the Language (Hausa), People (Hausawa) and Land (Kasar Hausa) acquired a distinct character derived from local concepts of geographic space.

This article sketches the process through which the Hausa became cartographically visible, from the formation of local traditions of autochthony, to the physical transformation of Land through cultivation and construction, and to the political and intellectual process that culminated with the drawing of one of the oldest extant maps of Africa made by an African.

21st century Map of the Hausalands by Paul Lovejoy, shown as they were during the 18th century.

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Traditions of autochthony fixing the language and People onto the Land: on the creation of ‘Hausa’ and ‘Hausawa’.

Foreign origin?

There are a number of traditions that relate the origin of the Hausa language and its speakers. The most popular tradition is the legend of Bayajidda (or the Daura chronicle) which is documented in internal accounts with various versions written in the 19th century, recounting how a foreign hero from the north-east (either Bornu or Iraq) intermarried with local ruling queen of Daura) and from his progeny emerged the founders of the dynasties of the main Hausa states.1

In attempting to historicize the Bayajidda myths of origin, historians have for long recognized the the limitations of the legend's various and almost contradictory accounts, they thus regard the different variations of the legend as reflecting the exegencies of regions rulers and elite who composed them at the time (ie; Sokoto’s sultan Muhammad Bello in 1813 and the Sokoto scholar Dan Tafa in 1824) who were in their origin, external to the subjects they were writing about.2 (the Sokoto state subsumed the various Hausa states in the 19th century)

Indigenous origin.

Conversely, political and ethnic myths of origin related by Hausa scholars and oral history tended to emphasize autochthony, by utilizing themes such as the hunter-ancestor figure and emergence of the first/new/original man from “holes in ground”, both of which are themes that are featured commonly among other African tradition myths of origin.3

There are a number of oral traditions that have been recorded from some Hausa settlements in Zamfara, Katsina, and southern Azbin saying that the ancestors of the Hausa people in those localities had emerged from "holes in the ground".4

In the 19th century account of the foundation of the Hausa states of Zamfara and Yawuri written by the Hausa scholar Umaru al-Kanawi ; he writes that a “new man” (Hausa: mazan fara) came from the “bush” (daji) as a hunter selling his game meat, and gradually grew his settlement and from which emerged Zamfara, Umaru then adds that in Yawuri, hunters that lived in the forest conquered the area and established themselves. In Umaru’s version of the Bayajidda legend, the man who intermarried with the Daura queen is left unnamed and his origin is left unknown, while the Queen's rule and her attributes are all emphasized.5 In all his accounts of Hausa origins, Umaru considers “hunters” and "new men/first men” from the “bush" as as pioneers in establishing the Hausa settlements.

Similarly, in the “song of Bagauda”, which is an oral account in the form of a poem recorded among Hausa speakers in Kano and is reputed to be a repository of the region's political history, the poem’s king-list begins with the hunter figure of Bagauda without mentioning his origin —in a manner similar to how Umaru introduces his "new men" and hunter figures— the poem also adds more information revolving around themes that feature in Hausa concepts of geographic space. with the hunters transforming into cultivators and clearers of land, and the cleared settlements eventually turning into a large towns.

"Bagauda made the first clearing in the Kano bush. It was then uninhabited jungle, He was a mighty hunter, a slayer of wild beasts". The poem continues, recounting how his settlement attracted many people who then became farmers;

"The encampment became extensive, They cut down the forest and chopped it up, They cultivated guinea-corn and bulrush millet such as had not been seen before".6

These accounts contain faint echoes about the formative stages of Hausa society and could thus be supplemented by linguistic and archeological research into the expansion of the Hausa language and its speakers from the western marches of the lake chad region into what is now northern Nigeria and southern Niger.7 These early Hausa communities were originally hunters who later became farmers8, and they established settlements surrounded by their farms, which then grew into large towns and cities encompassed by wall fences (birni) which then became a characteristic part of the settlement hierarchy and the nucleus of the emerging Hausa polities centered in cities.9

Gold earrings, pendant, and ring from the grave of a high status Woman Durbi Takusheyi, Katsina State, Nigeria

This process by which the people who speak Hausa and the land in which they settled was developed through farming, the construction of urban settlements and establishment of state systems inorder to acquire a distinct identity is referred to as Hauzaisation.10

Transforming the Land: an ecological and cultural process to create ‘Kasar Hausa’

The emergence of Hausa as distinct identity across the Hausalnds can thus be viewed ecologically; it involved the Hausaization of the land, the conversion of bush and woodlands into parkland farms and open savanna, with a marked reduction of the tsetse-infested areas, and the increasingly intensive exploitation of the land for seasonal grain cultivation and a fair degree of cattle-keeping.

The largest of the nucleic Hausa communities often established themselves at the hill bases of the region's granite inselbergs, which were traditionally revered as places of the most ancient settlement and religious importance that served as centers of powerful cultural attraction. These inselberg settlements featured stone circles, grinding and pounding stones, pounding hollows, and terraced stone field walls which stresses their primarily agricultural, sedentary character.11

the Dalla hill of Kano, considered a scared site

From these inselbergs with their commonly fertile bases such as the flat-topped, iron-bearing mesas of Dalla and Gorondutse in Kano, as well as Kufena and Turunku in Zaria, that there developed a new system of moving into and clearing the plains to grow millet and sorghum by relying on the annual rains of May to September, and by using the large Hausa hoe manufactured using local and regional iron, in breaking the hard soil of the plains to create the extensive farmlands that came to characterize the region’s landscape.12 In many rural Hausa traditions, the legendary figure Bagauda is the culture-hero of the field through his planting of crops and he is symbolized as a hoe thus signifying strength, skill, and ritualistic power.13

Farming outside the Hausa town of Batagarawa in Katsina, photo from the 1960s

Beside its intensive grain cultivation, Hausaland is suited to livestock, the region's extent of grassland and the confinement of tsetse to its southern most extremities are doubtless partly the result of agricultural land-clearance and the pasturing cattle. It was thanks to this agro-pastoral economy that Hausaland, which may have been sparsely inhabited in the first millennium, later came to support relatively dense populations

It's within this process of cultivation, herding and settlement that further Hausa notions of geographical space emerged with their distinction between the city (birni) with its surrounding farmland (karkara) on one hand, and the “bush” on the one hand. Concepts which were central in the establishment of early state systems with the symbiotic and antagonistic relationship between the inhabitants of both spheres which came to be recognized as two distinct political domains, with the city state emerging as the primary political unit of the Hausalands 14

the city of Kano (foreground) and its farmlands an bush (background), photo from the 1930s

The process of state formation thus begun in the nuclear region of Daura, Hadejia and Kano in the early 2nd millennium, followed by Zazzau and Katsina in the early to mid second millennium, and later expanded through the plains of Zamfara and Kebbi in the 15th century.15 These are the states that would from then on appear in external accounts as the most dominant political entities of the Hausalands.

Political and Physical construction of a society: Rulers, cities and Walls.

The 15th century is seen as a 'watershed' in Hausa state formation with the emergence of substantial city-states in eastern Hausaland such as Kano, Katsina and Zazzau, significant cultural, commercial and political developments and expansion of external contacts, followed by an increase in the degree of cultural and commercial incorporation into a wider world (less orthodox pg

The political economy of Hausaland—merchants and their caravans, city-based rulers and their cavalry—was planted and grew in the urban settlements and their surrounding farmlands whereas the countryside/bush retained settlements which seem not to be conventionally Hausa in form but could nevertheless support and interact with the urban centers as part of a wider, receptive system.16

The Hausa cities were economic centers with professionalized markets, town walls and royal palaces. These cities were planned and constructed, houses were renovated, and town walls extended, like in much of west africa, urban design in the Hausalands was total. Hausa cities, which were planned geometrically and ritually inspired, often carried a semiotic basis derived from Hausa concepts of geographic space; urbanity in the Hausalands was thus determined by local exigencies and influenced by Islamic principles.17

The Friday Mosque, the Court Building, and the Palace of the Emir were built in the very center of the walled towns. Around the urban political and religious center, the cities were divided into wards, each with its own neighborhood mosque and the residence of the ward head , the urban built-environment and its surrounding farmlands developed a specific character.18

Zaria mosque built in the early 19th century.

Hausa urban spaces were usually limited by city walls, which turned a settlement linguistically into a town/city. These walls were originally built following the contours of the landscape, the walls at Turunku were constructed to surround a group of inselbergs, while the walls at Kufena and Dumbi are built close to the foot of inselbergs, enclosing them.19

In Kano, the series of fortifications cover an area around 20km in circumference, extend to heights of upto 9 meters, and were surrounded by a 15-meter deep ditch. The walls of Zaria, were about 6 meters high and covered a circumference of 16 km. In both cities, as with the rest of Hausa urban settlements, the city walls enclose agricultural and residential land, and they were originally constructed in the 12th century, afterwhich they were expanded in the 15th and 17th century.20

city walls and ditch of Kano

The city walls and their enclosed inselbergs were clearly imposing expressions of power, designed to be seen from afar, their guarded gates, naturally also served to keep inhabitants in. Thus internal and external accounts of Hausa cities usually reported about the constitution of the wall, as well as the names, numbers and locations of the city gates.

Gates of Bauchi

Locating ‘Hausa’ (the language), ‘Hausawa’ (the people) and ‘Kasar Hausa’ (the lands) in external cartography.

The first explicit external account of the Hausa lands was made by Leo Africanus' "Description of Africa" written in 1526 , and it goes into vivid detail on the political, economic and social character of the city-states in stark contrast to the cities' relative cartographic invisibility prior. Leo’s vivid account of the Hausalands which most scholars agree was second-hand information received while he was in the city of Gao21, was the result of the political and intellectual integration of the Hausalands into the larger west African networks which initially led to external scholars moving into the Hausalands, and later, Hausa scholars moving outside the Hausalands and thus transmitting more accurate information about their home country.

detail from Leo Africanus’ 16th century map of Africa showing atleast 4 of the 6 Hausa cities he described; Cano (Kano), Zanfara (Zamfara), Casena (Katsina) and Guangara (unidentified Hausa city southeast of Katsina). 22

By the late 15th century, a series of political and commercial innovations made the Hausalands a magnet of west African and north African scholars who then increased external knowledge about the Hausalands. These include the Timbuktu scholar Aqit al-Timbukti who taught in Kano in the late 1480s23, the maghrebian scholar Al-Maghili who passed through Kano and Katsina in 149224, the maghrebian scholar Makhluf al-Balbali who taught in Kano and Katsina in the early 1500s.25

Leo’s lengthy account of the Hausa city-states features the most visible outward markers of Hausaization including the architecture, walls, farmlands, crafts industry and trade, he describes the "cloth weavers and leather workers" of Gobir, the "artisans and merchants" of Kano, as well as the "abundant grain, rice, millet, and cotton" of Zamfara, but the most importantly, he notes defensive walls of the cities; describing Kano that "It has a surrounding wall made of beams and clay".26

It was these features of defensive walls and extensive cultivation, (as well as trade and handicraft industry) that became the most visible cartographic markers of the Hausa city-states, transforming them into cartographically visible polities in external accounts.

Around 1573-82, the geographer Giovanni Lorenzo d'Anania, who obtained his information about the Hausalands from a Ragusan merchant who had spent some years in the African interior, listed Kano with “its large stone walls”, as one of three principal cities of Africa alongside Fez and Cairo.27

The late 16th century and mid 17th century west African chronicles of; Ghazawat Barnu (chronicles of Bornu), Tarikh al-Sudan (chronicle of the sudan) and Tarikh al-Fattash (chronicle of the researcher) which were written in Ngazargamu, Timbuktu and Dendi (ie: outside the Hausalands) make detailed descriptions of the Hausa city-states such as Katsina, Kebbi and Kano. The cities’ are often introduced within the context of the wars with the Bornu and Songhay empire, and the west African networks of scholarship and trade, showing that they were doubtless written for a west African audience already relatively familiar with the region. The Hausalands’ inclusion in the chronicles is significant in affirming the urban, mercantile character of the Hausa states.28

By the 18th century, external descriptions of the region now explicitly included the names of the language (Hausa), the people (Hausawa/Hausa), and their land (Kasar Hausa/Hausalands).

While the cities were by then fairly well known in external accounts, most of these accounts referred to the Language of the region, the People living within it and the Lands they controlled, using exonyms derived from the empire of Bornu (which was for long the suzerain of several Hausa city-states), eg in the mid 18th century, the German cartographer Carsten Niebuhr was informed by a Hausa servant living in Tripoli about the lands of “Afnu and Bernu”, the servant’s language is also called Afnu —the word for Hausa in Bornu— rather than Hausa.29

However the use of such exonyms in external accounts immediately gave way to more accurate endomys once the Hausa begun defining their own region to external writers. In an account written by the German traveler Frederick Horneman based on information given to him by a travelling Hausa scholar, as well as his own travels in west Africa during 1797, he writes that:

"Eastward from Tombuctoo lies Soudan, Haussa, or Asna: the first is the Arabic, the second is the name used in the country, and the last is the Bornuan name"

This introduces for to readers the first explicit use of the ethnonym Hausa in external texts. Horneman then continues describing the people, language and states of the Hausa that were doubtlessly given to him by the Hausa scholar, writing that;

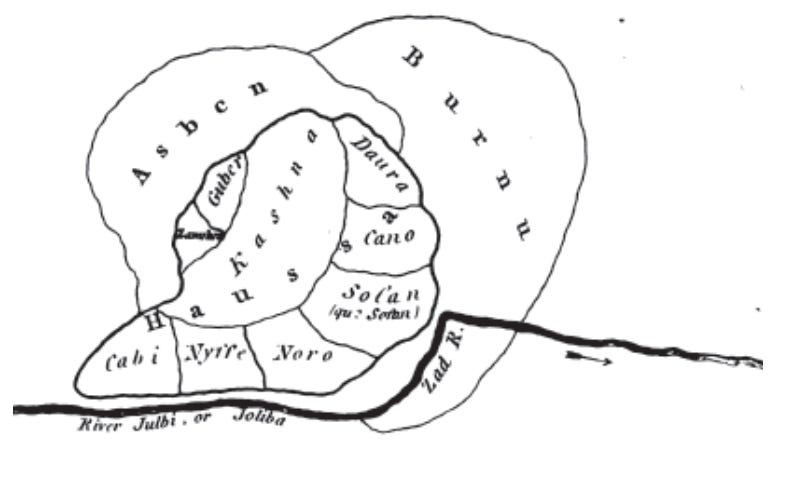

“As to what the inhabitants themselves call Hausa, I had as I think, very certain information. One of them, Marabut (scholar), gave me a drawing of the situation of the different regions bordering on each other, which I here give as I received it."30

The map is a very valuable source representing how Hausa travelers mapped their home countries, and is arguably the oldest extant map drawn by a west African about his homeland. The states of Bornu, Asben (Air sultanate), and Katsina are depicted as the largest empires. Around Katsina, minor Hausa states are arranged: Gobir (“Guber”), Zamfara, Daura, Kano (“Cano”), Sofan, Noro (These were likely part of Zaria31) , Nupe (“Nyffe”), Kebbi (“Cabi”). The map is oriented northwards and all Hausa states are drawn together forming a circular area and the entire region is labeled “Hausa” (ie; Hausalands) ; to the north, the east and the west Hausa is bordered by other states; to the south the “Joliba” (Niger and Benue) make up the natural boundary. Beyond this, no states are added.32

comparing the Hausa scholar’s 18th century map with Paul Lovejoy’s 21st century map of the Hausalands.

conclusion: On Africans defining their geographic space.

Tracing the emergence and descriptions of African regions in external texts reveals their use of indigenous African concepts of geographical space as well as the physical and intellectual process through which African land was transformed by cultivation, and construction, as well as the active participation of African scholars and travelers in the intellectual process of mapping their Land as it appears in external documents.

The use of locally derived names (endonyms) for the language, people and lands shows how spatial concepts and cartographic markers on the African continent were often dictated by the African groups whose lands they were describing. The 18th century map of the Hausalands was a culmination of the physical and intellectual process of transforming the region occupied by Hausa speakers into a cartographically visible region with a distinct Language, People and HomeLand.

Subscribe to my Patreon and Download books on nearly 2,000 African scholars from the 11th-19th century , and Books on Hausa Geography and cartography.

Huge thanks to ‘HAUSA HACKATHON AFRICA’ which contributed to this research.

Some considerations relating to the formation of states in Hausaland by A. Smith 335

Origins of the Hausa: From Baghdad Royals to Bornu Slaves pg 172-179 in “A Geography of Jihad” by Stephanie Zehnle, Some considerations relating to the formation of states in Hausaland by A. Smith 336-337)

General History of Africa volume 4: Africa from the 12th to the 16th Century pg 268)

The Hausa and the other Peoples of Northern Nigeria 1200 – 1600 by M. Amadu

A Geography of Jihad” by Stephanie Zehnle pg 180)

The 'Song of Bagauda': a Hausa king list and homily in verse—II by M Hiskett pg 113-114)

Towards a Less Orthodox History of Hausaland by JEG Sutton pg 181-183

Being and becoming Hausa by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 174)

Being and becoming Hausa by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 155).

Hausa as a process in time and space by Sutton pg 279–298

Some considerations relating to the formation of states in Hausaland by A. Smith, The walls of Zaria and Kufena by Sutton

Early Kano: the Santolo-Fangwai settlement system by M. Last

The 'Song of Bagauda': a Hausa king list and homily in verse—II by M Hiskett 114–115)

Being and becoming Hausa by Anne Haour, Benedetta Rossi pg 66)

Towards a Less Orthodox History of Hausaland by JEG Sutton pg 183)

Towards a Less Orthodox History of Hausaland by JEG Sutton pg 184)

Ross, Eric: Sufi City. Urban Design and Archetypes in Touba, Rochester 2006, p. 23

Hausa Architecture by (Moughtin, J.C.: p. 4.)

The walls of Zaria and Kufena by j. Sutton, Kufena and its archaeology by J. Sutton

The Oxford Handbook of Islamic Archaeology pg 495), The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa by Timothy Insoll pg 298)

Timbuktu and Songhay by J. Hunwick pg 272

Timbuktu and Songhay by J. Hunwick pg 52

Islam in africa by N. Levtzion, pg 379

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 55-56

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg 284-288)

History of West Africa - Volume 1 by J F A Ajayi - Page 334

Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire by John Hunwick pg xli, History of the First Twelve Years of the Reign of Mai Idris Alooma of Bornu

The Life of a Text: Carsten Niebuhr andʿAbd al-Raḥmān Aġa’s Das innere von Afrika

by Camille Lefebvre 286,293

The Journal of Frederick Horneman's Travels from Cairo to Mourzouk By Frederick Horneman pg 111)

pre-sokoto Zaria had vassal states of Kauru, Kajuru and Fatika that were relatively semi-autonomous unlike the more centralized nature of control its Hausa peers such as Kano and Katsina exerted over their vassals (see MG smith’s Government in Zazzau pg 78-79)

A Geography of Jihad” by Stephanie Zehnle pg 124-125