Revolution and Upheaval in pre-colonial southern Africa: the view from Kaditshwene.

On the myth of "mfecane"

Historical scholarship about 19th century southern africa has long been centered on the notion of the so-called mfecane, a term that emerged from colonial era notions that implicate King Shaka and the rise of the Zulu kingdom as the cause of unprecedented upheaval, political transformation, and intensified conflict across the region between the 1810s-1830s. As a cape colonist wrote: "the direful war-wave first set in motion by the insatiable ambition of the great Zulu conqueror rolled onward until it reached the far interior, affecting every nation with which it came in contact"1. One of the nations supposedly engulfed in the maelstrom was the Harutshe capital of Kaditshwene, the largest urban settlement in southern Africa of the early 19th century.

Research over the last two decades has however convincingly shown that the “mfecane” is a false periodization not grounded in local understanding of history, but is instead a scholarly construct whose claims of unprecedented violence, depopulation and famine have since been discredited. This article explores the history of the Tswana capital of Kaditshwene from its growth in the 18th century to its abandonment in 1823, showing that the era of revolution and upheaval in the Tswana states was neither related to, nor instigated by the Zulu emergence of the early 19th century, but was instead part of a similar process of state consolidation and expansion across southern Africa.

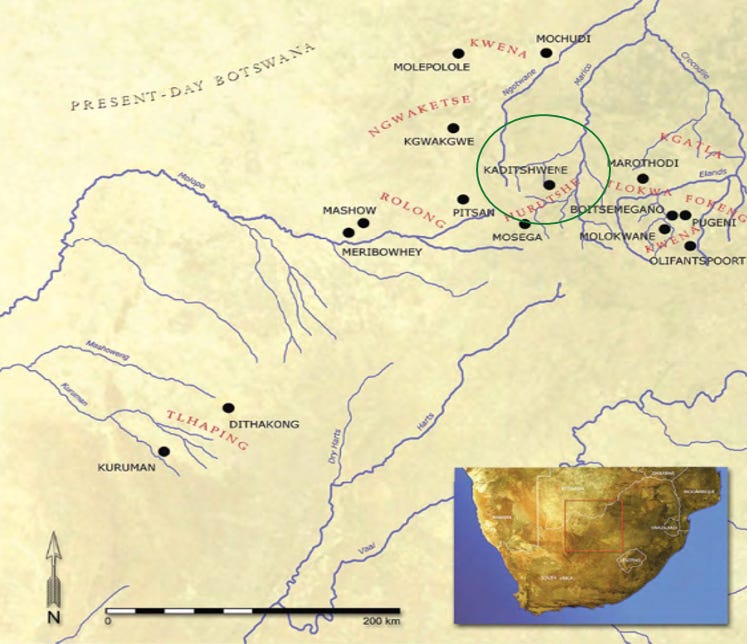

Map showing some of the major Tswana capitals in the late 18th century including Kaditshwene, and the Hurutshe state (highlighted in green)

Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:

Earliest Tswana communities in southern Africa, and the emergence of social complexity (3rd century -14th century)

There’s now significant archeological evidence of the arrival of sedentary homesteads, iron working, pottery, and plant and animal domesticates into south Africa by bantu-speaking groups in several waves beginning around 250AD, these groups often travelled along the coast and thus settled near the south African coast to exploit its marine resources and to cultivate the sandy soils adjacent to the sea, the latter soils were often poor and quickly depleted which periodically forced their migration for new fields.2 The interior of southern Africa was occupied by various pastoral-forager communities who were among the earliest human ancestors in the world. known in modern times as Khoi and San, they traded and intermixed socially over centuries with bantu-speaking communities. Both the oral traditions and the reports of European missionaries and travelers confirm that the forager communities and the bantu-speaking groups often lived on amicable terms near each other but also warred for resources and on occasions of transgression,3 aspects of San culture were also adopted in Tswana origin myths to affirm the latter's ancestral links with the region.4

The earliest states in south eastern Africa emerged at Schroda and K2 (south-africa) around 850AD, at Toutswe (Botswana) in 900AD, at Mapungubwe (south-Africa) in 1075, at Great Zimbabwe (Zimbabwe) in the 12th century, and at Thulamela south-Africa) in the 13th century5. By the 14th century, complex chiefdoms of lineage groups were spread across most of south-eastern Africa including in what is now southern Botswana and central south-Africa, in the heartlands of the Tswana-speakers (a language-group in the larger bantu language-family) from which the Hurutshe state emerged.

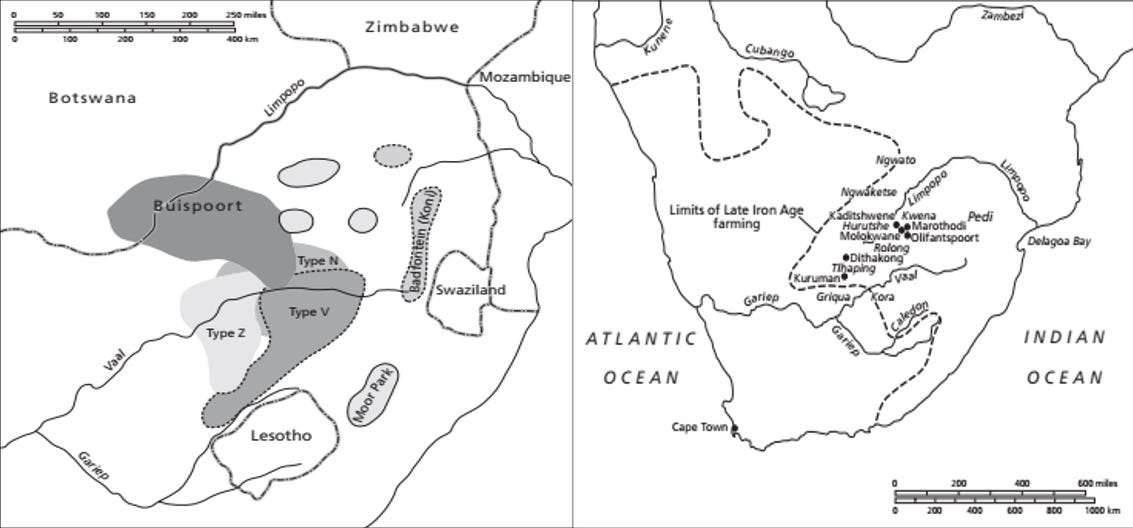

Map showing the distribution of Tswana (and Nguni) stone-wall settlements after the mid-15th century, Map showing the location of some late 18th century Tswana capitals

Early Tswana lineages and states: 14th-18th century

Among the Tswana speakers, states were often identified by the name of the founding ancestor of the ruling chief's line of descent6. Across the wider region, submission to authority was prompted by military protection and gaining access to productive resources such as arable land and cattle rather than an acceptance of the legitimizing authority, this preserved the right of expression of open dissent in public forums which became a feature of the region's statecraft.7 settlements reflecting early Tswana culture in the region are first dated to about 1300 and many of the traditions of the old Tswana ruling lineages date their founding genealogies back to the early second millennium, possibly indicating that these traditions refer to ancestors who headed the descent line and inherited the chieftaincy prior to their arrival.8

Radiocarbon dates from settlements near Kaditswene confirm that Tswana speakers had settled there as early as the 15th century. The extensive use of stone as a building material started in the late 17th century, and had by the mid 18th century grown into aggregated stonewalled settlements, such as Kaditshwene and several others. The material-cultural and stratigraphic record of these sites indicate however, that they were not occupied for extended periods, suggesting that Tswana capitals including Kaditshwene were frequently relocated.9In the 18th century, a number of Tswana polities emerged central southern Africa. These states came to be known with reference to the ancient lines of descent that had long been in the region such as the BaHurutshe, BaFokeng, BaMokgatla and BaKwena among others10 (despite the Ba- prefix, these are Tswana dialects rather than different languages11).

From lineage segmentation to large chiefdoms: the emergence of Harutshe (1650-1750)

The historiography of southern Africa contains many records about the separation/segmentation of genealogically linked lines of descent into smaller lineages that eventually founded the early polities of the region. These segmentations occurred from the late 1st/early 2nd millennium upto the early 18th century. The size and complexity of the resulting sociopolitical formations and their interactions, including trade and warfare, reflect development over a long period prior to the earliest written records about them. Several explanations for this segmentation have been offered including; conflicts in authority and succession that were resolved by migration rather than military contest/subordination;12 ecological stress during periods of scarcity;13 and social rules prohibiting endogamy.14 The process of segmentation was in part enabled by the availability of territory relative to the small size of the early states.

Among the Tswana lineages, the BaFokeng and the BaHurutshe separated in the 15th century, after a contest over authority forced the former to migrate away eastwards.15 Of the three remaining lineages, the BaHurutshe cited a great progenitor who predated those of their peers, this progenitor was Malope I whose three sons by order of birth were Mohurutse, Mokwena and Mokgatla.16 Several versions of this aetiological legend exist in Tswana culture and were employed to endorse the genealogical ranking of the various Tswana lineages, according to which the Hurutshe were “a higher nation” than their peers because they were born first.17 These three lineages would also split further over the 16th and 17th century.

In the early 18th century, the BaHurutshe separated into two lineages with the first establishing Kaditswene and the second at a nearby town called Tswenyane, by the late 18th century however, the ruler of the latter faction, named Senosi, was subject to the authority of the boy-chief at Kaditswene named Moilwa II and the his regent named Diutlwileng.18 Across 18th century southern Africa, segmentation of the old lineage groups stopped and reversed in most cases, as powerful states begun to consolidate their authority over smaller states.19 In the Tswana states, the increasing accumulation of wealth and the centralization of political power by rulers led to the growth of large aggregated capitals of the emerging Tswana states one of which was the Hurutshe capital of Kaditswhene.20 (and others including the Ngwaketse capital of Pitsa)

ruins of the Ngwaketse capital of Pitsa, established in the late 18th century.21

Kadisthwene as the pre-eminent Tswana capital, and the era of Tswana wars (1750-1821)

In 1820, a missionary named John Campbell, travelled to Kaditswene. He was known locally as Ramoswaanyane22 (“Mr Little White One”) and his accounts provide the richest accounts of the city at its height. Campbell estimated the Hurutshe capital’s population at 20,000 shortly after his arrival, but later adjusted the number to 16,000 in his published journal.23 Both figures compare favorably with the population of cape-town estimated to be about 15-16,000 in the early 19th century.24 Kaditswhene's characteristic dry-stone walling, like in several other Tswana cities, was used for the construction of assembly areas, residential units —which enclosed houses, kitchens and granaries—, as well as stock enclosures.25 Campbell described the handicraft manufactures of Kaditshwene that included extensive smelting of iron, copper and tin for making domestic and military tools, leather for making cloaks, sandals, shields, caps; as well as ivory and wood carving for making various ornaments,26 commenting about the quality of their manufactures that "they have iron, found to be equal to any steel" and that every knife made by their cutlers was worth a sheep both in the local market and among the neighboring groups with whom they traded, selling copper and iron implements for gold and silver27. The discovery of several iron furnaces and dozens of slag heaps in the ruins collaborates his observation.28

ruins of Kaditshwene (including Tsweyane above) overgrown with shrubs

Campbell also witnessed one of the proceedings of the assembly of leaders (pitso ya dikgosana) comprising of 300-400 members, which was held at Diutlwileng’s court on 10 May 1820 on matters of war against a neighboring state (most likely the Kwena) ostensibly for seizing their cattle, as well as to consider the request to establish a mission at the Hurutshe capital.29 During the mid 18th century, Harutshe enjoyed a form of political and religious dominance over their mostly autonomous neighbors30, including the Ngwaketse and the Kwena chiefdoms31 and in the late 18th/early 19th century, Hurutshe asserted its authority over several of the neighboring chiefdoms, wrestling them away from the neighboring Ngwaketse and Kwena chiefdoms, such as the statelets of Mmanaana and the Lete which were renown for their extensive iron-working and whose conquest allowed the Hurutshe to control the regional production and distribution of iron and copper.32 In the 1810s, the Harutshe were at the head of a defensive alliance with several Tswana states that were at war against the resurgent chiefdom of Ngwaketse after loosing its tributary, Mmanaana, to the Ngwaketse in 1808. 33 By 1818, Kaditswehe had campaigned in Lete, and fully incorporated it into their political orbit with their chief, relocating his capital to Tsweyane34. When another missionary named Stephen Kay visited Kaditshwene in August of 1821, the forces of Hurutshe were caught up in a war with the Kwena.35

The fall of kaditshwene: from Queen Manthatisi to the invasion of Sebetwane. (1821-1823)

Contemporaneous with the emergence of large Tswana states like Hurutshe was the emergence of Tlokoa state led by the BaTlokoa, the latter were a segment of the earlier mentioned BaKgatla who had split off from their parent lineage around the 17th century and furthermore into the 18th century with the establishment of several small chiefdoms east of Hurutshe.36 By the early 19th century, several of these small chiefdoms were united under Queen regent Manthatisi's Tlokoa state whose expansionist armies were campaigning throughout the region and incorporating neighboring chiefdoms into her growing state37, some of her wars were fought with the Harutshe in 182138, and with several of the emerging BaFokeng chiefdoms including the expansionist armies led by an ambitious ruler named Sebetwane39.Sebetwana united several segmentary BaFokeng groups and raised a large army, but rather than settling to fight against the more powerful armies of the Tlokoa, he chose the old response of migration, and thus travelled northwards into what is now modern Zambia, but along the way, his armies faced off with several of the chiefdoms in the region including the Hurutshe.40

Oral records and contemporary written accounts indicate that the Hurutshe regent Diutlwileng, died in a war with Sebetwane in a battle fought around April 1823. Diutlwileng had led the Hurutshe armies upon receiving a request for military support from his vassals the Phiring and the Molefe. the Harutshe capital of Kaditshwene was sacked shortly after his defeat41. Hurutshe then fell under the suzerainty of the large Ndebele kingdom as a tributary state.42 The Ndebele kingdom led by Mzilikazi, extended from southern Zimbabwe (where it had subsumed the medieval cities of the Rozvi and Great Zimbabwe) and over parts of northern south-Africa. Sebetwane on the other hand subsumed the Lozi states of modern Zambia into his large kingdom of Kololo43. The protracted process of state consolidation that begun in the late 18th century ended with the emergence of large kingdoms in the mid 19th century, the centuries-long segmentation of the Tswana and other bantu-speaking groups of southern Africa was reversed as complex states emerged, expanded and evolved into large Kingdoms such as Ndebele, Kololo and the Zulu, while Kaditshwene fell in the upheaval of the era's political transformations.

Revolution and Upheaval across southern africa: from Dingiswayo to Shaka of Zulu.

Similar revolutions and upheavals were observed across the region. The migration of lineages, over short and long distances in south-eastern Africa dispersed chiefdoms across the regions of; KwaZulu-Natal, Trans-Kei, Maputo (Delagoa) Bay, Swaziland, Transvaal, and Lesotho. Over many centuries, the smaller chiefdoms succumbed to sociopolitical domination and incorporation by others as ambitious chiefs (and later; Kings) consolidated their hold over people and territory through diplomacy and war; expanding their influence and control to create large kingdoms in the mid 19th century.44

Examples include the Mathwena kingdom under king Dingiswayo of (r. 1795-1817) who is better known for mentoring Shaka of the Zulu kingdom, he greatly consolidated his rule over surrounding states under his authority (including the zulu), largely through military conquest and diplomacy, achieving the former by introducing a series of military innovations, and the latter through intermarriage.45 he expanded export trade in ivory, leather, cattle, and other commodities especially with the Portuguese at Delagoa Bay46 and turned his capital into a major craft manufacturing center, establishing a manufactory of kaross-fur textiles that employed hundreds of workers.47 The archetype of this era was undoubtedly the Zulu kingdom under the reign of King Shaka (r. 1816-1828). The Zulu were initially under the wing of Dingiswayo's Mathwena kingdom as a tributary state, but later broke off and grew into the preeminent military power in south-eastern africa. Shaka’s reign was marked by his famous military campaigns, as well as his diplomacy, trade and innovations which resulted in the consolidation of Zulu authority over much of the surrounding states in the Kwazulu-Natal region.48

Colonial warfare and the invention of “mfecane”.

The early 19th century period of political transformation across southern africa was termed mfecane by colonial historians. The term mfecane was purely academic construct coined in the late 19th century by various colonial writers and popularized by Eric Walker's "History of South Africa" written in 1928, but it wasn’t an indigenous periodization used by the southern Africans whose history the adherents of "mfecane" were claiming to tell49. Their central claim that mfecane was an unprecedented era of widespread violence, famine and loss of human life that begun with the emergence of the Zulu kingdom has since been thoroughly discredited in recent research since the 1990s, by several historians and other specialists50, showing that not only were the political processes in several places (such as the Tswana chiefdoms) outside the sphere of the Zulu’s influence, but also that many of the wars which occurred between the expanding states (such as the Tswana wars of the late 18th century, Manthatisi’s campaigns of the 1810/20s, and Sebetwane's wars with Hurusthe and other groups in early 1820s) were unrelated to —and mostly predated— the Zulu’s emergence 51. Intertwined with the theories of a Zulu-induced chain-reaction of violence, were the old Hamitic-race theories which had been used in the historiography of Great Zimbabwe to argue for its foreign foundations, but were now repurposed for south-African historiography. Scholars such as the colonial state ethnologist Paul-Lenert Breutz, wrote in two widely read publications of Tswana history in 1955 and 1989, that the stone structures of Kaditshwene “were not characteristic of either Bantu or Nilo-Hamitic peoples" and should "be attributed to some Hamitic or Semitic race" who supposedly built them in ancient times, and that they had been destroyed by the Bantu-speakers during the mfecane, a pseduo-historical argument that he maintained despite being aware of campbell’s writings, radiocarbon dating, and the traditions of the BaHurutshe who still lived next to the ruins.52

The purported loss of life during the mfecane, which colonial scholars such as George McCall Theal (the “father of south-African history”) advanced based on impressionistic observations made by early 19th century travelers about the ruins of Kaditshwene and other capitals53, and the very conjectural claims made by European traders in the Kwazulu-Natal region —claiming over a million deaths attributed to the Zulu wars—, has been dismissed as "slim or non-existent" by recent research, which used contemporary literature by 19th century travelers to show that the both the Tswana and Kwazulu-Natal regions were very densely populated at the time, much to the surprise of the same travelers who had received reports about the regions’ apparent depopulation.54

While the adoption of maize/corn in the KwaZulu-Natal region during the late 18th century (but not in the Tswana regions until late 1820s55), and its vulnerability to climate extremities compared to indigenous sorghum, did result in famine in parts of Kwazulu-natal in the mid 1820s, external accounts written by European traders in the region routinely exaggerated accounts of the Zulu's military campaigns for causing them, implicating the Zulu in the destruction of the food systems, and subsequent famine and the "depopulation" of the area, yet droughts were a recurring theme in southern Africa's ecological history including a much larger drought in 1800-1803 that hit the cape colony as well as the interior.56 The fact that most of the european traders’ accounts are centered on the notion of the depopulation of the Kwazulu-Natal area and thus the myth of the “empty land”57, raises further suspicion, as the various europeans interests were concerned with bringing the region under colonization. "Claims of the deliberate destruction of food as a cause of widespread famine are thus at best exaggerated to serve as narratives of depopulation, and at worst inextricably tied to narratives of white civilising missions amongst the wars and migrations of savage tribes".58

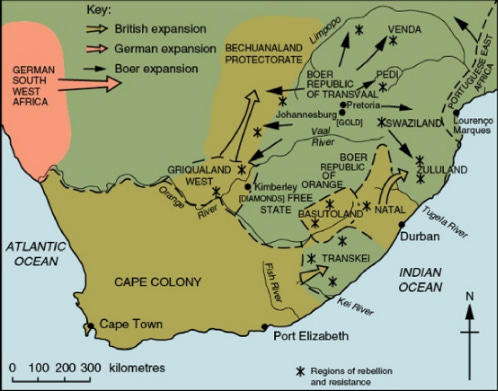

Map of southern africa in the late 19th century showing the directions of colonial invasions

Conclusion: the view from Kaditshwene

"Mfecane" was an academic construct that was weaponised in colonial and apartheid literature to justify European colonization and apartheid rule in southern Africa.59 As one south African historian observed, the mfecane “is essentially no more than a rhetorical construction - or, more accurately, an abstraction arising from a rhetoric of violence".60 As shown in the example of Harutshe’s political history, there's little evidence that a unique wave of internecine violence emerged in the 1820s across a previously tranquil political landscape, and even less evidence that a singular factor such as the Zulu or the Ndebele were responsible for this paticular era's warfare.61

Rather, southern Africa in the late 18th and early 19th century witnessed the emergence and consolidation of large states from segmentary lineage groups following an in increase in socio-economic stratification and political amalgamation,62 and throughout these processes, rulers transformed their scope of authority from heading small chiefdoms in mobile capitals, to controlling diverse groups and vast territories in large kingdoms using innovative and elaborate institutions of governance; in what could be better termed as a “revolution”.63 While migration and lineage segmentation were in the past the only response to conflicts in authority, the large states of the 18th/early 19th century southern Africa increasingly chose consolidation through both diplomacy and open war, leading to the emergence of states such as Hurutshe, which were eventually subsumed into even larger kingdoms.

The view from Kaditshwene is a portrait of the political transformation and upheaval of the south-eastern Africa in the 19th century, a city that was simultaneously a beneficiary and a causality of the era's political currents.

Read more about the mfecane, Kaditshwene and south-African history on my Patreon

THANKS FOR SUPPORTING MY WRITING, in case you haven’t seen some of my posts in your email inbox, please check your “promotions tab” and click “accept for future messages”.

A Tempest in a Teapot? Nineteenth-Century Contests for Land in South Africa's Caledon Valley and the Invention of the Mfecane by Norman Etherington pg 206

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 8)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 237-238)

The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 67

The origin of Zimbabwe Tradition walling by Catrien Van Waarden

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 90_)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 7)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 239)

A tale of two Tswana towns: in quest of Tswenyane and the twin capital of the Hurutshe in the Marico Jan C.A. Boeyens 10-11)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 238)

Modes of Politogenesis among the Tswana of South Africa by Alexander A. Kazankov; pg. 123-134

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 240,244)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 244-245, Nomadic Pathways in Social Evolution by Kradin, Nikolay N pg 124-125

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 51, 114)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 239-240)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 245)

A tale of two Tswana towns: in quest of Tswenyane and the twin capital of the Hurutshe in the Marico Jan C.A. Boeyens pg 13-14)

A tale of two Tswana towns: in quest of Tswenyane and the twin capital of the Hurutshe in the Marico Jan C.A. Boeyens pg 23)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge 116),

The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 71)

Reconnecting Tswana Archaeological Sites with their Descendants by Fred Morton

A tale of two Tswana towns: in quest of Tswenyane and the twin capital of the Hurutshe in the Marico Jan C.A. Boeyens pg 19)

A tale of two Tswana towns: in quest of Tswenyane and the twin capital of the Hurutshe in the Marico Jan C.A. Boeyens pg 5)

Africa's Urban Past By R. J. A R. Rathbone pg 6

The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 69)

Travels in south africa vol. 1 by James Campbell pg 275-276)

Travels in south africa vol. 1 by James Campbell pg 277, 272)

The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 73)

Travels in south africa vol. 1 by James Campbell pg 259-265)

The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 70)

Conflict in the Western Highveld/Southern Kalahari c.1750-1820 by Andrew Manson

A tale of two Tswana towns: in quest of Tswenyane and the twin capital of the Hurutshe in the Marico Jan C.A. Boeyens pg 21)

Conflict in the Western Highveld/Southern Kalahari c.1750-1820 by Andrew Manson

A tale of two Tswana towns: in quest of Tswenyane and the twin capital of the Hurutshe in the Marico Jan C.A. Boeyens pg 27-28)

Marothodi: The Historical Archaeology of an African Capital by MS Anderson pg 17)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 247-8, 259)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 262-261)

Marothodi: The Historical Archaeology of an African Capital by MS Anderson pg 17)

Africa in the Nineteenth Century Until the 1880s by J. F. Ade Ajayi pg 115)

Africa in the Nineteenth Century Until the 1880s by J. F. Ade Ajayi pg 116)

A tale of two Tswana towns: in quest of Tswenyane and the twin capital of the Hurutshe in the Marico Jan C.A. Boeyens pg 7-8, )

The Bahurutshe: Historical Events by Heinrich Bammann pg 18-19)

Africa in the Nineteenth Century Until the 1880s by J. F. Ade Ajayi pg 116-117

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 116)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 171-173)

Sources of Conflict in Southern Africa, c. 1800–30 by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 8)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 165-170)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge 181-184, )

A Tempest in a Teapot? Nineteenth-Century Contests for Land in South Africa's Caledon Valley and the Invention of the Mfecane by Norman Etherington pg 204)

Mfecane Aftermath: Reconstructive Debates in Southern African History by Thomas Dowson, Elizabeth Eldredge, Norman Etherington, Jan-Bart Gewald, Simon Hall, Guy Hartley, Margaret Kinsman, Andrew Manson, John Omer-Cooper, Neil Parsons, Jeff Peires, Christopher Saunders, Alan Webster, John Wright, Dan Wylie

A Tempest in a Teapot? Nineteenth-Century Contests for Land in South Africa's Caledon Valley and the Invention of the Mfecane by Norman Etherington pg 204-5)

In Search of Kaditshwene by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 5

Marothodi: The Historical Archaeology of an African Capital by MS Anderson pg 41)

Tempest in a Teapot? Nineteenth-Century Contests for Land in South Africa's Caledon Valley and the Invention of the Mfecane by Norman Etherington pg 206)

The Late Iron Age Sequence in the Marico and Early Tswana History by Jan C. A. Boeyens pg 74)

Sources of Conflict in Southern Africa, c. 1800–30 by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 29)

The Demographics of Empire by Karl Ittmann et al pg 120

Climate, history, society over the last millennium in southeast Africa by Matthew J Hannaford pg 19)

Mfecane Aftermath: Reconstructive Debates in Southern African History, by various

Savage Delights: White Myths of Shaka by Dan Wylie, 19)

Sources of Conflict in Southern Africa, c. 1800–30 by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 15)

Sources of Conflict in Southern Africa, c. 1800–30 by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 30)

Kingdoms and Chiefdoms of Southeastern Africa by Elizabeth A. Eldredge pg 320)

I'm excited for this I just bought Dan Wylie's "The Myth of Iron" 😎